pdf: 1969

Written in March 2001, this is essentially autobiographical, but gives a good flavour of the epoch (free concerts, street/political theatre, the beginning of squatting and the London Street Commune, skinheads v. long hairs, Schools Action Union, The Festival of Light, strikes, etc). It also contains some reflections on other aspects of theatre (e.g. Brecht).

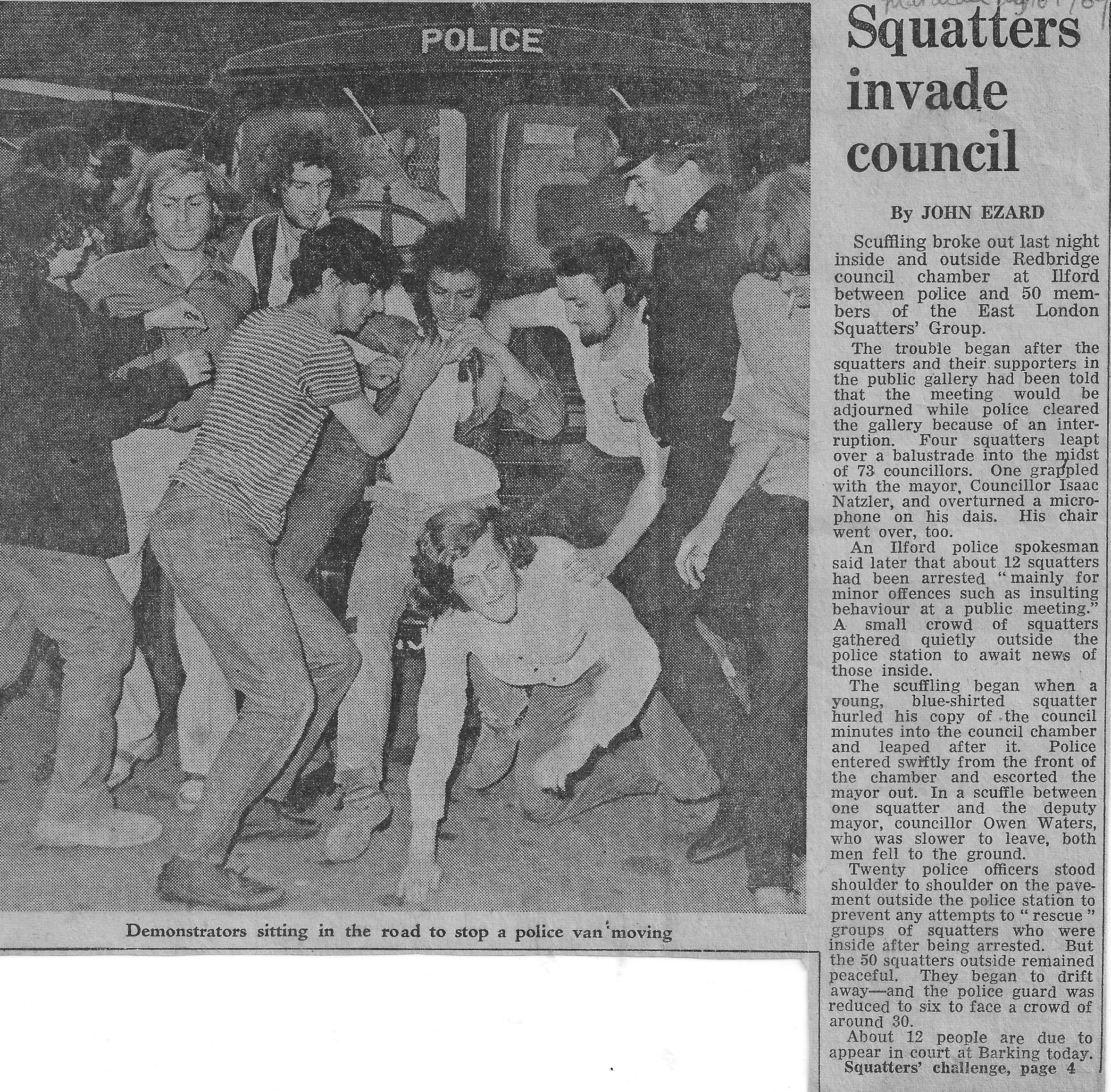

The photo here is of 144 Picadilly, squatted in 1969 and talked about in this article.

1969:

revolution as personal and as theatre

1968, for all of those who wanted to live against a world without future, was a great year. But as almost always at that time, I was a late developer. It was 1969 before I got going.

1969 was good but wasn’t great: it seems useful to reflect on this period a bit, as a bit of contrast with the madness of today’s normality.

PREAMBLE: MY BACKGROUND

I turned 19 in the summer of ’69. It was an exciting period for me like losing my political virginity (my real virginity was lost a little later, and a little late: as I said, I was a late developer).

For years I’d been very lonely, a very withdrawn adolescent, with very few friends, and with these my only passion, apart from music, was Left-wing “politics”, in the sense of responding to the news in the media. I’d been brought up in an ex-CP liberal-lefty family. They were basically libertarian in the sense that they neither encouraged nor discouraged, approved nor disapproved of anything we did, at least when it came to anything ‘moral’ or social. It was a ‘make your own mistakes, just get on with it’ attitude that bordered on indifference.

My parents allowed my youngest sister to sleep with her English teacher boyfriend in the house (her room was a little separate from the main flat we had), and he’d have breakfast and sometimes lunch and supper with us in the main flat (if Chris Woodhead is reading this, which he surely is, he must be green with envy!). They were very much into High Culture. My mother was a consumer and appreciater of culture – she sang in the Philharmonic Chorus and was an antique dealer and had the very best of tastes and was a great admirer of Freud. My father was more a creator of art – illustrations, paintings, arty games. German-born, he liked Kafka, Schwitters, the arty aspects of the Dadaists, the surrealists, the arty Jacqueline de Jong/Asgar Jorn wing of the post-’62 S.I. (he knew nothing of the radical wing, and, judging from his later reactions to my attitude towards art, wouldn’t have liked it one bit), didn’t like pop art, but liked Johnny Heartfield and Georg Grosz, quite liked Brecht [1], but preferred Pinter and Becket (whose aestheticisation of non-communication and meaninglessness justified his own), had a cultural (rather than political) opposition to journalism and psychoanalysis along the lines of Karl Kraus. Likewise, his critique of Stalinism was of its social realist art (he’d left the Communist Party in 1950 because of Stalin’s persecution of artists – almost all of his CP friends left only 6 years later; this was certainly a brave and exemplary act)(he’d also gone into Czechoslovakia a week or so after Hitler invaded in March 1939, to help get Communist and Jews out by supplying them with false papers, an even braver act). Apart from the use of culture and art as a mediation in discussions with his colleagues and friends, art for him was a retreat into abstraction, the pleasure of being alone creating. He painted abstract paintings, and was a lecturer in design. Very modern. He was generally gentle, but, typically, hardly communicated about daily life at all, for which mathematical games and abstract paintings were a soothing consolation.

Up till then my politics had been pretty much as a lefty spectator – I’d gone along on CND demos from the age of 8, with one or more members of my family. One of my 3 older sisters knew people who were part of the Committee of 100, one of the more radical sections of CND; she got arrested on a sit-down in Whitehall or somewhere, and had only the very best things to say about the cops – they were all so polite, warning her that they were about to arrest her, asking her if she was ready to be picked up by the four of them, picking up her shoe, etc. (early 60s); my posh uncle paid the fine. I’d of course gone along on demos, but had only shouted slogans maybe and had just marched, most of the time feeling that everyone was together, apart from me. It was a fantasy place to meet people which I was incapable of doing since I hadn’t sussed that meeting always depends on your own initiative in the end. Although I must have liked the atmosphere – the trad jazz, the beatnik bohemianism of it all, nevertheless, demos to me became a banality, a quarterly ritual, almost always on a Sunday, something to go and feel a part of some movement but not really moving. Undoubtedly for a lot of older – mainly, but not only, Middle Class – teenagers than me it had been an opportunity to get away from the family for a few days and maybe get off with girls or blokes and just have fun, regardless of the political content which was often a pretext. As a pretext though, it did have a rebellious image, especially when headmasters banned CND badges in schools. So it attracted some of the right people. A year or so ago I had a dream (which in fact was a simple memory of what it was like) of a CND march entering London after over 3 days marching from Aldermaston, and everyone on the pavements clapping the marchers and some of the bystanders joining in and the marchers took over the whole road, which was wide and there were no cars. The dream had a warm glow to it ~ it was a memory of a sweet naivety. Nowadays the idea of clapping people who’d walked a long way against nuclear weapons, or about anything, would be unheard of. Most of this time my politics had been down to arguing with Tories and others at school about Vietnam and immigration policy, taking my opinions from Tribune or the New Statesman, or, by ’67, International Times, Oz and Private Eye. I liked Che Guevara and Fidel Castro (partly because he’d said he was in favour of the abolition of money), but not Mao particularly – the shameless personality cult was totally off-putting to me. In ’67, at the age of 17, I made a little badge out of letraset, with the words “Conform! – Be a hippy!” on it. Very radical – but I only wore it once in public, I was so inhibited. In ’68 I went on Vietnam demos but never hit a cop or chucked anything. I liked what went on in Paris in May, but, being in Berlin to learn German, didn’t follow it too closely.

At Christmas 1968 a CP dissident friend/lover of my dad gave me “Obsolete Communism: The Left-Wing Alternative” , a book by Daniel and Gabriel Cohn-Bendit – a book which, in a standard political ultra-left anarchist-type way, clarified some ill-formed ideas in my head, and revealed some new things as well.[ 2 ]. As a result of this book I started to read Solidarity texts. English Solidarity had been mentioned in the book, so I spent the next 3 months reading what seemed like almost everything they published, a kind of intellectual approach to revolt, but then coming from a Middle Class family (and being lousy at sports), this initial approach was almost inevitable. At the end of April ‘69 I got in touch with Solidarity over the phone and they put me in touch with people in the North London Revolutionary Socialists (which included people some of whom were later to become part of the Angry Brigade). This was quite a major step for me, because I’d never got involved directly in any activity other than putting a Lefty/liberal political poster up in my window at home and trudging on demos, and had very little social life. Suddenly I was meeting lots of people in London about my age, when previously I’d had virtually only three London friends. Suddenly I found different places to visit, different actions to be involved in.

For the anti-government strike on May 1st I handed out Solidarity leaflets which I’d not even half read, with a bunch of people I felt pretty nervous with, but who were friendly enough. Later I got involved in a strike, well supported by Solidarity, of a shitty factory near Wembley (Punfield and Barstow). Solidarity were sometimes a bit militant, but they didn’t ever try to manipulate working class struggles they were involved in; their weakness was that they often held back from a proper open dialogue of differences – but then what Organisation with a capital O doesn’t? (it’s the problem of thinking yourself of having a specialist role rather than a fellow proletarian with a very different history of alienation who has to struggle to communicate). But they did offer genuine support, in the form of propaganda and helping on pickets (in fact, late into the summer, I got arrested for sitting down on the picket line). However, most of the time on the picket line, us “politicos” would just speak to each other, whilst the strikers – all Asian – remained in their closed network. Personally, I can’t remember having any proper conversation with any of the strikers. I remember one guy, who was later a leading light in the Angry Brigade, suggesting we blow up the factory’s electricity generator. People didn’t criticise it for its substitutionism (the guy had hardly even spoken to the strikers, and hadn’t even been much on the picket line) but only said that that was something that was only worth doing if and when the strike had failed (though that’s not really true). In most of these conversations I had nothing really to say – I lacked confidence and experience and didn’t know what I thought, though I did think blowing up of the generator idea was a bit weirdly conspiratorial: however, you never really know what you think until you start to say it, which I didn’t. But there was a constantly fluid atmosphere of discussion and argument – some people, for instance, criticised the name ‘Solidarity’ because it sounded too nicey and other-directed. People would argue about the differences between East London Solidarity, more working class and utterly down to earth in its texts, whereas North London was more theoretical – and people would argue the limits of both (though nobody argued what it might mean about the de facto hierarchy in Solidarity).

At a free concert near Parliament Hill we handed out leaflets (these I did read) attacking the largely hippie audience, amongst whom were my best friend at school and his friends who I knew a bit. One of them said we were just full of hate. Here it is:

WHAT THE FUCK ARE YOU DOING HERE ?

YOU DESPISE YOUR BULLSHIT CONVENTIONAL TELLY ORIENTED FOLKS WHO SIT ON THEIR ARSES IN THEIR PLASTIC PADS AND RECEIVE THEIR CULTURE SERVED UP IN HANDY PACKAGES. DON’T YOU ?

THEN WHAT THE FUCK ARE YOU DOING HERE. ?

YOU HATE YOUR PARENTS YOUR BOSS, YOUR TEACHERS —- THEIR VALUES,THEIR AMBITION, EVERYTHING ABOUT THEM STINKS. THEY HAVE YOUR WHOLE BLOODY LIFE MAPPED OUT FOR YOU. DO YOU THINK YOU CAN ESCAPE BY GROWING YOUR HAIR TAKING DRUGS,SMASHING UP TUBE TRAINS,OR BY GOING TO THESE SHIT ‘FREE’ HIP CONCERTS.

SO WHAT THE FUCK ARE YOU DOING HERE ?

CAN’T YOU UNDERSTAND THAT THESE SCENES ARE NO DIFFERENT FROM THOSE THAT YOU ARE KICKING AGAINST ? —— TAKE YOUR PICK, SUNDAY NIGHT AT THE LONDON PALLADIUM, BEATLES, PINK FLOYD ITS ALL THE SAME SHIT. YOU JUST SIT THERE ON YOUR ARSES AND JUST SOAK IT ALL UP. SO YOU WANT TO FREAK OUT.WELL YOU CAN’T. NOT WHILE YOU KNOW THAT TOMORROW YOU HAVVE TO RETURN TO THE SYSTEM YOU ARE TRYING TO ESCAPE FROM. FOR UNTIL WE DESTROY THEIR WHOLE SYSTEM, TEACHERS BOSSES IMPOSED AUTHORITY AND MONEY, WE ARE CAUGHT UP IN IT AS MUCH AS DESPICABLE PARENTS, AND UNTIL IT IS DESTROYED WE ARE INCAPABLE OF CREATING ANYTHING…………

FUCK THE SYSTEM – IT FUCKS YOU!

Though in retrospect I really like this leaflet, despite its nihilist limitations, at the time I felt a little embarassed and not articulate enough to argue about it.

The day before the Free Stones Concert in Hyde Park we stuck up stickers in Goldsmiths College saying simply, “Riot! – Hyde Park tomorrow!”, which I’d written in felt-tip markers. We’d gone along partly to help a Punfield and Barstow striker make a speech and collect money for the strikers, who weren’t getting strike pay. At Goldsmiths that day there was a teach-in partly organised by Malcolm McLaren, later of Sex Pistols/Virgin ad fame. He’d collected a motley crowd of male star rebels, many of them media hate figures. These included the former Notting Hill rent collector for Rachman, Michael X, whom everyone was supposed to support because he’d re-modelled himself along Malcolm X lines and had got a lot of hassle from the cops, getting arrested for contravening the Race Relations Act. Also, the dockers leader, CP shop steward, Jack Dash, and Alex Trocchi, former member of the SI and low level promotor of heroin chic along William Burroughs lines. All of them were considered heroes by the underground press such as IT and OZ. I remember on that day the student union hacks – “I’m a moderate!” – were preventing non-student union members from going into the free festival-cum-teach-in: our little group opened up a side-door and told everybody how to get in. In fact this was far more interesting than what was going on on the stage, which was little more than just a radical version of a chat show. When a group of radical womens liberationists disrupted the whole thing, and were treated in a blatantly patronising manner by the stage, we felt we had to support the women, though, quite honestly, I remember feeling that everyone was a bit on show, including the women. At the end of the day, a few cops came into the college, and were met with indifference by everybody. McLaren was furious, rightly, but none of us did anything to attack them – well, no one got arrested, despite the hash smoking. We used the free student facilities to print a leaflet for the Stone concert, which was a milder more political version of the leaflet distributed on Parliament Hill and was partly written by me, reflecting a less gutsy approach:

STOP!

THINK!

What the hell are you doing here?

Have you come here to escape the boring repetitiveness of your schools, your jobs, escape your boss, your parents, your hang-ups, the fuzz, the politicians; the system that kicks you around and tells you what to do?

Do you control your life?

Aren’t you pissed off with this hypocritical, repressive, profit-mad society which denies you control of your life, makes you merely a cog in a massive machine which exists only for those who press the button; for THEM not us?

Do you control your mind?

You are free to speak your mind, but is your mind itself free? Through the TV, the newspapers, the schools, the colleges, advertising, your mind is moulded, so that it accepts the system.

If you step too far out of line, if you get high, if you squat, they bust you.

Do you control your culture?

O.K. So you’ve come to 3 free concerts every summer in Hyde Park, but the pop industry is profit-orientated, commercialized, 90% computerized bullshit. Somewhere someone’s getting fat on your bread.

Are you involved in the music?Do you think that by sitting on your backside sucking in what’s being churned out, you become part of it?The music may be good, but have you stopped to consider what’s behind it?

You have no real control over your life, over your mind, over your culture-so what are you going to do about it?Do you care?Do people around you care?Have you asked them?

YOU HAVE THE POWER TO CONTROL YOUR LIVES, SMASH THE SYSTEM AND ULTIMATELY CREATE A SOCIETY WHICH EXISTS FOR US, AND NOT FOR THEM

On the day of the Stones concert I managed to lose my ‘comrades’ (as we used to say and some people still do) in the crowd and bumped into the hippy type friend and his girlfriend who’d been on Parliament Hill and we popped some pills. At that sombre moment when Jagger read out a poem by Shelley in memory of the recently deceased Brian Jones, a load of cans and bottles were chucked at a large crowd who were standing up and obscuring the view. An innocent age. Just as they started playing ‘Street Fighting Man’ I suddenly saw in the distance my ‘comrades’ prancing and jumping and dancing up and down with great big flaming torches held up high, chucking the leaflets up into the air to distribute them. When the song was over, the creepy presenter denounced, through the monopoly of the mike, my group for trying to spoil people’s fun. I heard later that they’d been taking the piss out of him, clearly not his idea of fun.

The Guardian, July 1969

Also during this summer I got involved in the re-birth of modern squatting in Redbridge, East London (Andy Anderson of Solidarity had written a little history of the post World War ll squatting movement, when 100s of thousands of returning servicemen and their families took over empty properties to re-house themselves after the bombing). The local council had called in thugs, some of whom were members of Mosley’s Fascist lot, to illegally evict squatting families. A pregnant woman had been chucked down the stairs and had lost the baby. So people from all over piled down there to protect another family the night their eviction had been predicted. Only they didn’t turn up that night, but the next, when I’d gone home to sleep after a sleepless night waiting to beat them up. So they were repulsed without me. However, I continued going there, sometimes chopping and changing days with Punfield and Barstow, where the strike was. One day we went to the public gallery of the council, where the question of squatting was low down on the menu. People shouted through it, because it was the only way not to fall asleep during the long proceedings that had nothing to do with why we were there. When the question of squatting finally came up, there was uproar, and the chairman of the council closed the meeting. Some of us – not me – jumped over into the council meeting area and one took the mayor’s chain and medallion off his neck. Then the cops piled in and started pushing everybody out. The guy who took the mayor’s medallion gets nicked, one of our group. Loads more people get nicked. We all rush to the car park and try to stop the cop van from getting out, kicking the sides and doors, blocking the exit. A French guy says “If I were back home we’d have been turning over cars by now”. Instead, we all lined up outside the police station to demand to know what had happened to our friends – what they’d been charged with, had they phoned a solicitor, etc. The cops push us back a little, demanding we form a single file. I ask one cop why, he says he’s only doing his job, I say “That’s what they said at Nuremberg” and he then grabs me by the arm and nicks me. This was the first time in my life I’d been arrested, my first direct experience of the police: reading about them and hearing other people’s experiences of them might help but you only really know the cops when you get nicked. Despite a bit of secondhand knowledge, I was really surprised by this seemingly unwarranted arrest, surprised by having my arm twisted behind me: this wasn’t what had happened to my sister 6 years previously. I was shocked when one of the cops threateningly called me a “Stupid cunt”, when I was forced to give my fingerprints because one of the others who’d been nicked had been leant on – not quite beaten up, but we could all hear his cries. How naïve, how Middle class. I was charged with the heinous crime of “obstructing the footpath” but when my trial came up a couple of months later, I got off. I was defending myself without a solicitor and, although I felt proud of myself, it was really due to the fact that the cop came out with the wonderful statement that “he would have been obstructing the footpath if he’d stayed there a few seconds longer”, to which the clerk of the court made one of those sneering eyebrow-raising facial expressions which said “what a moron!”. Shamefully, I was so full of myself for getting off that I was really scathing towards the guy who’d taken the mayors’ chain off, for pleading guilty, even though it was under pressure from an uninformed newly substituted solicitor (that was another thing I learnt at that time: defence solicitors are often as much your enemy as the prosecution ones, a banality, I know, but it was all new to me). When I think about it, I still feel ashamed for putting him down when he already felt really down.

This was the summer where squatting really took off. It started off for homeless families, who very often had been helped by politicos like us, and often were represented in their negotiations with the council by ‘professional’ squatters like Ron Bailey, who’d been on the periphery of Solidarity, and self-styled anarchists like Jim Radford. But very quickly it extended to young homeless people. The West End was full of young, mainly working class, teenagers who’d left their families and come to London for a bit of adventure but had found the streets not paved with gold, and were forced to sleep rough. Though some of them were kind of “hippies”, most didn’t define themselves like that or even really fit the description. They organised themselves into the London Street Commune, with the help of an older radical who, for the media, called himself Dr.John, but was, in fact Phil Cohen, a guy who’d been involved in King Mob. (King Mob were famous in the scene for helping to liberate Powis Square in Notting Hill, and for dressing up as Father Christmas, going into Selfridges and giving out toys to the kids; when Security nicked Santa Claus, the kids were astonished that the toys had to be handed back; these stories doing the rounds at the time were my only notion of what ‘situationist’ ideas were all about). Under the banner of ‘The London Street Commune’ disparate groups took over 144 Piccadilly, a vast rambling building at Hyde Park Corner, opposite the Queen’s Buckingham Palace garden, virtually next to the Hilton Hotel. They were denounced by the media as ’filthy hippies’ despite the fact that most of them weren’t, and by Ron Bailey, who said that squatting was for families, not for single people. Nice guy. Our lot went along to support it, though personally I found the whole atmosphere very confused and, having a rather formalistic stick-in-the-mud ideology of workers councils with mandated delegates and constant meetings, borrowed from my reading of Hungary 1956, I couldn’t see how people were really organising collectively. But they did, though there was a lot of cliquishness.

One incident that has hardly ever been mentioned about the squat was when a bunch of media-incited skinheads turned up in the night to shoot air-guns at the squatters. They were pelted from the roof with heavy water-filled carpet bowls, thousands of which had been stored in the empty building prior to the take-over (presumably the carpet bowl company was using the place as a warehouse). Skinheads at that time weren’t really racist – many gangs included a couple of blacks – but had arisen in reaction to the love ‘n’ peace ‘feminine’ image of Middle Class hippies (much of which, in Britain at least, was really a manipulated creation of the cadres of the music and youth culture industry): hence the close-cropped hair, the big workman’s boots, the braces and turned-up trousers – an exaggeration of the male working class image. Despite the love ‘n’ peace image of the hippies, those heavy carpet bowls thrown from on high easily beat the skinheads’ air-guns, and their attempt to invade the squat was quickly defeated.

What did defeat the squat, was the invasion of cops: over 200 “hippies” were arrested, many beaten up and most kept in jail for a minimum of a week, many a lot longer. An hour or so before the cops invaded a faction of the squat (the squat was full of different cliques) led by the charismatic Syd Rawell got wind of the invasion but kept the news for his little group only, getting only his followers out before the cops moved in. After the beatings of the hippies the cops proceeded to smash the place up – skirting boards and all, just so the Press could print some lovely snapshots of how dreadfully the filthy hippies had treated such a wonderful building. John Lennon then went on TV to offer the London Street Commune a little island off Scotland, an offer taken up by Syd Rawell, who represented himself as the London Street Commune spokesman, when well over 200 of the Street Commune were inside (whose presence there was partly down to the fact that Rawell hadn’t told them about the impending invasion, of course). Some of those who managed to avoid being nicked, but not part of Rawells’ clique, then went on to squat a place in Endell Street, near Covent Garden, and were then reinforced for a while by the dribble of people being released on bail from prison. A meeting of ultra-left supporters – us, anarchists, libertarians etc. – was held with some of the Commune at Freedom in Whitechapel when some skinhead guy came in with a ‘comrade’[3] and asked if he could bring his gang in to discuss things together, especially our common hatred of the cops. Everyone said, “Sure”, and the next moment about 25 skinheads walked in. For a moment I thought there was going to be a fight, considering what had gone on at Piccadilly, but in fact they genuinely wanted to talk (it is possible that they hadn’t heard about the air-gun/carpet bowl battle). It shows how gangs and sub-cultures at that time were far more open and fluid and less rigid than they are now: it would require a massive social crisis, brought about by the increasing mass of marginalised individuals themselves, for such a possibility to return.

That summer I was very much the activist – we’d go on demos (say, about Ireland) and shout “2 – 4 – 6 – 8 – copulate and Smash the State!” (not that I was doing either), or go on pickets, say of Pentonville Prison, for a black guy who’d been imprisoned there pending deportation. But it was also integrated into what for me was a a fairly exciting social life as well – say going to Portobello at the end of Saturday, picking up the fruit and salad stuff that had been left over, and having a party with some wine others had nicked (me, I never nicked at that time). Or going to a housewrecking party in Muswell Hill and shooting off by car at the end of it to help out some people who were organising the first squat in Brighton – a squat of some old Ministry of Defence Territorial Army buildings not far up from the clocktower, hanging out on the roof all week-end, getting into arguments with young CP militants about smoking dope in the squat (me, I smoked just once at that time).

In late July, the School’s Action Union (SAU), along with some older ‘radicals’ (some were and some weren’t), organised a ‘living school’ which was originally to be held at the London School of Economics (LSE), the most famous hotbed of ‘revolutionary’ activity in the country (they’d been the first to have a sit-in and had become famous for destroying a locked gate across a corridor designed to control them). When the governors withdrew permission for the SAU conference to take place there some SAU activists took over a section of the college which could only be entered by means of a ladder through a window. Others diverted the venue to Conway Hall, less than half a mile away. Me and the people I knew argued that we should all continue at LSE, because a situation of confrontation was the best form of radical education. But the ‘radical’ specialists, like Michael Duane (former headmaster of Rising Hill School, a State school which had been closed down for being too progressive) and Sheila Rowbotham, already a bit of a feminist celebrity, claimed that they wouldn’t be able to get their ideas across in such an atmosphere (which showed how much their ideas were not really a practical attack on this society). I should say that at this time I put my arguments only one to one with individuals or groups of individuals: I had no confidence to speak out in such a large meeting (several hundred people), despite the fact that this was an immediate practical question. The majority voted to disband the small occupation of LSE and continue the ‘living school’ in the traditional ultra-left environment of Conway Hall. It was there that a group of radicals who’d been at Cambridge University talked and performed examples of short plays they’d performed, uninvited for the most part, in schools, plays which parodied the education system (some of them – namely, John Barker and Jim Greenfield – later became the leading lights in the Angry Brigade, a far cry from their Please Stop Screaming Theatre, or PSST, days). This inspired me, and some SAU people, all but one of whom I’d not met before, to try to do something similar in London later in the year – in September.

For most of the others, the SAU activists, the project of doing what was termed “guerrilla theatre”- going uninvited into school playgrounds – was seen as a means of getting new SAU contacts in those schools which hadn’t formed a group. For me, not having been involved in SAU (I’d left school in January 1968) it was an exciting thing to do, and a belated rebellion against school, a rebellion once removed, as it were (a timid soul, one of the rare rebellious things I’d done at grammar school was to walk all the way on a cross country race, for which crime the house master had threatened to bring in a magistrate friend of his to intimidate me). We rehearsed the play under the direction of a guy who’d been part of the political theatre crowd at Cambridge – Bruce Birchall, a student drop-out from whom the term “filthy hippy” must have originated (he probably thought that dirt must be next to ungodliness; when a girl he had a brief relationship with cleaned up his Notting Hill flat whilst he was out, he exploded in fury; he was as neurotic about cleanliness as some people are about dirt). Nevertheless, we all got on with him o.k. and no-one mentioned his hygiene.

In Cambridge, apart from the guerrilla theatre in schools, he’d put on “The Marat/Sade”, a kind of Brechtian style ‘revolutionary’ play which was a play within a play – it’s full title being “The persecution and assassination of Jean Paul Marat as performed by the inmates of the asylum at Charenton under the direction of the Marquis de Sade”, written by Peter Weiss in 1964, performed in all the good theatres throughout Europe. It’s still used as a standard acting school dramatic exercise, a classic study in Brechtian drama. In London it had been performed by the Royal Shakespeare Company with Glenda Jackson as the inmate playing Charlotte Corday, the woman who assassinated Marat (the most well-known representative of the extreme left during the French Revolution), an appropriate part for a woman who was to later become a New Labour Mini-star. Particularly as the character of the inmate was a woman who had sleeping sickness and kept on dozing off half way through her counter-revolutionary discourses. Clearly a role that required absolutely no acting ability on her part whatsoever. The Cambridge production had starred Jim Greenfield and John Barker, who later on became the well-known anti-heroes of the Angry Brigade, with Jim as de Sade and John as Marat (I think). Apparently, they’d gone round Cambridge after performances singing the songs in the streets and then went on to more practical attacks – window smashing and graffitti. I’m sure that this was something the Royal Shakespeare Company also did after the show in the Aldwych (Glenda Jackson’s Secret Past Horror Shock!) (not). Bruce’s Cambridge theatre lot also did a bit of clever “anti-theatre” stuff. There was a conventional theatre production of Max Frisch’s “The Fire Raisers” – a play, meant to be an allegory of the appeasement of Hitler during the 30s, which involves lodgers moving more and more drums of petrol into the attic of the landlords house, palming off the owners with claims that it’s not petrol or giving them reassuring excuses for its presence, reassurances that the owners wanted to believe. During the interval Birchall’s lot started rolling in drums which smelt of petrol into the foyer and the back of the auditorium, partly blocking the fire exits, telling everybody who looked, “Don’t worry, there’s nothing in them”, mirroring the play and panicking many of the audience, before they were kicked out. This was a bit like another group – in Leeds, I think, who did something similar with a cinema performance of Bunuel’s “Exterminating Angel”, an often claustrophobic film where, inexplicably, loads of bourgeoises find themselves stuck in a room for a long time, despite the fact that the door is wide open. The Leeds group chained up all the exits to the cinema. Since the film ends with the funeral of those who had died in the room held in a cathedral full of bourgeoises who then find themselves stuck there without any way of getting out, you can imagine how the audience trying to leave the cinema might have felt. At a Barcelona performance of the Marat/Sade during the early 80s, when the play ended with the uprising of the inmates against the bourgeoises who had come to watch the play a guy in the cheap upper circle seats threw an open plastic bottle of cheap wine into the expensive seats below. Inevitably, he got some hassle from security. The spectacle of the critique of the spectacle, whether it be Brecht, Weiss, Frisch or Bunuel, is not meant to be taken literally but followed at a few steps distance: if it were not for this albeit tiny distance, the mystification becomes apparent.

As far as I remember, Bruce wrote most of the script of the 10 minute play we were going to take into schools, though it was basically improvised as we went along and we wrote most of the leaflet that accompanied it. Often we rehearsed without him, mainly in a ramshackle disused factory which, I think, was the base for the Arts Lab, who allowed various groups to use it for free, unsupervised – for rehearsals, meetings or whatever. Imagine that now – no money to pay, no security guards. Another person who helped us out was Phil Cohen [4] and his girlfriend, Pam Brighton [5], who was involved in Agit-Prop Theatre, whose leading light was Roland Muldoon [6] . We also rehearsed at 144 Piccadilly. Shortly after the eviction there, we were putting part of the leaflet [7 ] together on the concourse outside Euston station. Two cops crossed from the far corner of the quadrangle, directly towards us, came up to us and told us we were not allowed to be there if we had no ticket for a train – bullshit, of course, since the concourse was full of people just sunning themselves. They threatened to nick us if we didn’t move on. This was the atmosphere towards long hairs at the time of 144 Piccadilly. Our only gesture of defiance was to shout, when we’d almost left the concourse and were about 100 yards from the cops, “Fuck the pigs!” or something similar.

The first school we went to was close to Baker Street – a secondary modern. We’d chatted with a couple of pupils there the day before and they said we should come along. We had no idea what to expect and were slightly worried we might be attacked. We rushed into the playground blowing whistles and beating a drum to attract attention, with school caps on our head, whilst the guy who played the teacher was dressed in a gown and mortar board, swishing a traditional cane. There were about 300 kids there and we started to shout “Roll up, roll up – for the education play. We’ve got exams, we’ve got prefects, we’ve got detentions, we’ve got the cane…roll up roll up…” The pupils immediately gathered round us, noisy but obviously interested. But very soon after starting the play a group of teachers stepped in. Surprisingly the kids tightened the circle round us so as to prevent the teachers from getting near us. Nevertheless, the teachers did eventually get to us, ordering us to get out. Their logic was impeccable: ”Have you got permission? You’ve got to ask for permission first. But we wouldn’t have given it to you anyway.” We argued with the teachers whilst handing out leaflets, fairly quickly leaving the playground to continue the play on the path just outside. The kids then gathered on the other side of the fence, some clinging to it, whilst some teachers tried to drag them or push them away, one even hitting one of the kids, scared we’d poison their innocent little minds. Despite threats of detention, and even suspension, the kids took little notice of the teachers, continuing to watch and listen to the play. Suddenly some of the kids shouted, “The cops are coming!” They arrived with a teacher and tried to drag one of us away. We pulled him free, to the cheers of the schoolkids. A teacher said, “You’re disturbing our kids” (my emphasis). “Do you want us to stay?”, I shouted. “YES!”, they yelled back in unison. (later, some of the others said that I’d been a little demagogic asking them that, but since it all turned out o.k. it was accepted). The cops made it clear we’d be nicked if we didn’t leave. After leaving, 4 boys slipped out from the school and came up to us to say we should come again and that they’d protect us from the cops, beat them up if necessary. Can you imagine that happening now? We learnt later that after we’d left there’d been a semi-riot when the 200+ pupils in the playground refused the Headmaster’s orders to get inside or be expelled. Not all the teachers were on the side of the Head either: a sympathetic art teacher helped produce anti-authoritarian posters which were put up round the school and teaching virtually came to a standstill. Three boys were accused of inviting us into the school and were threatened with expulsion.

On the same day, we quickly went onto another school – a grammar school close by, catching the kids as they left at the end of the day. And so it went on for four days, though nothing really was as good as the first school. The third school we went to they also called the cops, after having got the prefects to push the kids back away from us, and after the Head and a teacher having threatened to beat two of us up. The cops took our names and warned us about trespass. As we left kids were being pushed away from the windows whilst waving to us. A month or so later 250 kids in this school walked out in support of a teachers pay claim, with an SAU activist being suspended for it (“insubordination”).

The fourth school was a girl’s school with a liberal/progressive reputation. This was the only school where we thought we had permission to put on the play, but our friends there got it wrong, as the Head dispatched the only male teacher at the school who screamed at us “DON’T ARGUE!” when we tried to explain the misunderstanding, and when he threatened to call the cops, we left, in the interest of our friends, who could have been victimised if we hadn’t.

The seventh school was St.Paul’s Public School for Boys, run by a very publicly right-wing Head, who kept files on, and liked to personally interrogate, suspected druggies, threatening them with the courts if they didn’t grass on the grass smokers. There were several secret SAU activists who lived in fear of victimisation if the authorities found out. We’d had fairly typically middle class arguments about going to such a school, along slightly Lefty avant-gardist lines (well, we were meant to be recruiting for the SAU, and 3 of the 4 others were SAU activists) – i.e. should we go there since our main interest is in comprehensive and secondary modern schools in the most deprived working class areas. Nevertheless, the excitement and energy released from the momentum of creating situations in which the discussion flowed and the reality of social relations became glaringly concrete and immediate, meant our stodgy reasoning got dispensed with: St Paul’s was a ripe target because it felt it would be fun to do it there. And I, for the first time, was playing the Teacher in our play, because the guy who normally did it had a bad sore throat. The boys there don’t respond at first, but after a few minutes of banging, announcing and doing the intro, there’s a fair crowd, but some are hostile – one of us, who has the longest hair – gets water poured over him, and insults are shouted. [8]

Anyway, the play continued with brilliant me as Teacher, when the deputy Head came onto the scene and asked us to leave. We totally ignored him and continued the play.

Deputy Head: Will you please leave – you haven’t got permission.

Teacher (me!): These exams have been specially designed to test your intelligence and ability. Your whole future, your entire livelihood will depend on the next 3 hours.

Deputy Head (getting agitated): If you don’t leave I shall have to call the police.

Teacher (to deputy head): Late for my lesson again? – get to the back of my class!

Utterly baffled and frustrated, the deputy leaves to the sound of laughter from a few brave boys.

This was a good example of using a theatrical form as simply a pretext, a tool, for creating a situation quite untheatrical: i.e. exposing very concretely a hierarchical role and contradiction. Such a use of ‘theatre’ is only possible where people go in uninvited and where such people are not attached to the precise ‘artistic’ means of conveying a critique, but are more into shaking themselves and the situation up, singing its own tune.[ 9]

The play over, we got into a discussion which was quickly broken up when the bell rang for the end of break, everyone instantly rushing back into school. On the way out we are met by the cops, who gave us a mild warning about entering the premises without permission. We said it was highly unlikely permission would be granted, though why we bothered to speak to them about such things I put down to naivety. In the text we later produced there’s this interesting reflection, ”Anyway, in the event of us being given permission in any school it would seem as if the authorities were in league with us. The advantage of a surprise performance includes the spontaneity and relative openness (away from the presence of authority and the cramping influence of the classroom) of the reaction obtained. In this way we were making our position clear right from the start – allying ourselves with the pupils against authority. Only through this method could we hope to win the trust and confidence of the students.”

An hour or so after St.Paul’s we went off to a secondary modern school in Clerkenwell, near Kings Cross, where an anarchist friend of ours was a pupil. During the previous school year, after a molotov had burnt a hole in the door of the Head’s study, the head decided to ban boots in the school, an attack on the skinheads in the school, who were in the majority. They responded: boot prints appeared around the school, on the floors and walls and ceilings, drawings of boots were chalked up on blackboards, and finally the Head was presented in assembly with a gigantic papier mache boot. The Head felt compelled to unban the boots. So we longhairs arrive at this skinhead school, shortly after the eviction of ‘hippies’ from Endell St. squat, where the London Street Commune had gone after the eviction of 144 Piccadilly. We stay outside the school, because our friend hadn’t turned up and because a lot of the school seemed to be hanging around outside in a small square just outside the gates. We start the play but amidst cries of “Go back to Endell St!.” and stone throwing from some of the kids, we end it quickly as some of the skinheads start lifting a great big paving stone (we find out later that the Endell St. ‘hippies’ had appeared earlier that day at Clerkenwell Magistrates Court, just around the corner). We hand out leaflets, start talking to the boys about conditions in the school and what we think the education system’s all about. They all want an end to physical punishment, which wasn’t to be abolished in this country until the late 80s (not that humiliating kids in other ways isn’t equally miserable). No one wants school uniforms, but many want a smoking room and everyone wants “proper biology lessons”, which at that time were pitiful (probably they still are, but in a different modern way).

A tall spindly man appears, tells the boys to get out of the square and starts pushing them around. I say, “They’re allowed to be here. Who are you to tell them what to do? They can decide for themselves what to do.” The man, who turns out to be the Head, ignores us and strides angrily away back through the school gates to cries of “Bastard…cunt!”. The boys are more sympathetic towards us. “Let’s burn down the school!”, a couple of them say. Being a bit of Lefty still, I said, “What’s the point? – they’ll only send you to another.” “Shall we occupy the school?” one of them asks. “Yeah – if you want – we’ll help, but it’s up to you” was the gist of our different replies. Then the cops arrive. “Back into school!” the Sergeant orders. I say loudly, “They’re allowed out in lunchbreak. Why should they get back inside?”, (not the kind of mouthy role I’d play nowadays probably, but…)”Because I say so”. “Do you make the laws?”, “No, I interpret them”, “Maybe you bend them a little to suit your own ideas” – I was talking loudly – as much to him as to the boys of the school, performing the rabble rouser a bit.. After resuming ordering the boys about, he hurries after me when I’m a bit away from the others and says softly, “Look here, young Barabas [10], if ever I see you again I’ll pull off your beard and cut off your hair, you fucking long-haired wierdo.” I reply in a loud theatrical voice so others can hear – “What? Did you call me a fucking long-haired wierdo?”. “Are you calling me names? Are you calling me names?”, says the sergeant, putting on a better show of outrage, and promptly nicks me.

The cops meanwhile threaten everyone with being nicked for obstruction – both us “guerrillas”(it sounds better than ‘street theatre actors’) and the schoolkids, so everyone moves off from the square to a small park up the hill, and start sitting around in groups discussing schools, the cops and so on. A cop comes into the park and, pointing to one of us – Michael, says to the mainly skinhead schoolkids, “Do you want to grow up to be like them – filthy, long-haired, unemployed…? Silence. Michael asks them, “Well, would you prefer to be like him or like me?” “LIKE YOU!” they all shout back, and the cop (us politicos called them ‘pigs’ at the time) storms off.

Eventually all of us get nicked and one of us gets beaten up a bit by the cops. The cops who arrest the last two of us get thumped on the back by some of the skinhead kids. The kids swear and hiss and boo at the cops, some of them hing themselves at the gates round the back of the police station, trying to break them down. Solidarity, unity in anger – one of the best things in the world. Later on, the Evening News came out with the headline “Boys Incited To Burn Down School!”, whilst the Evening Standard said we’d offered the boys drugs and that a hundred schoolboys had chased two hippes and shouted and jeered at them. When the papers appeared, some of the boys were so pissed off they tore them up outside the school. Meantime, we were packed off to Ashford Remand Centre, even though our parents had turned up in court to put up surety for the bail which most of us had been granted (the only one of us that wasn’t was a couple of years older than us, the only one of us who was from a working class background – he went to Brixton for a week before bail was granted). There we were made to have a public cough ‘n’ drop medical inspection and a semi-public bath and then we had to wear prison clothes: my trousers were far too big – I had to permanently hold them to stop them falling down, and my shoes were far too small, cramping my toes. It was only 24 hours, but when it’s your first time in prison and you’ve got no idea how long you’ll be there, and you’ve never known anyone who’s been inside, it was a little worrying, though it was the boredom I remember most, because we were kept isolated for most of the time. I was so naïve, I remember being really outraged at the fact that teenagers were kept in prison without bail for 6 months or more before trial, at which they were often let off.

The leaflet we’d handed out in the four days of our guerrilla theatre actions advertised a meeting at my house on the afternoon we’d got nicked: 12 kids turned up, we didn’t, but the cops did, staying in a van outside, whilst one stood outside the front garden. For several months afterwards, my phone was tapped.The trial was almost 3 months later, and took 3 days. Like the whole of that summer, I suppose it was a kind of revelation for naïve little me. I hadn’t expected such a degree of lying on the part of the cops and hypocrisy on the part of the magistrate, though since then it’s something I take for granted. For instance, so that the Headmaster wouldn’t have to appear as a witness, and to give greater authority to the police, a Chief Superintendant claimed to have been there, and described everything that had happened to the Headmaster, though elaborating with a few extra lies. We were so taken aback by his convincing performance, and perhaps also stressed by the whole trial, that we began to question our own memories – had he been there and we hadn’t noticed? Was it not the Head who’d first remonstrated with us? The whole trial was awash with lies, of course, but the strange thing were the words they put into our mouths, words that had nothing to do with the way any of us would speak – e.g. the Sergeant said I’d shouted from the police car, “Go, lads, and burn down your school – we shall support you”. “Go lads” – like I was some public school prefect.

Article from “The Kilburn Times, end of December 1969:

BOYS TOLD TO TAKE OVER SCHOOL

CROWDS of schoolboys ran wild after two “hippies” incited them to “take over” their Camden secondary modern school or “burn it down”.

The boys, from the Sir Philip Magnus School, at Penton Rise, Kings Cross swarmed into the yard of Kings Cross police station when urged to free the “hippies” after they were arrested.

Prosecutor Mr. V. R. told a Wells Street magistrate that the schoolboys had been told “You can take over your school if you want to or burn it down. You don’t have to take any notice of the teachers.”

The schoolboys gave “a loud cheer and clapped”, he added.

In the dock were five young men charged in connection with the incidents.

N.B., 19, unemployed, of Aberdare Gardens, and P.S. 23, unemployed, of no fixed address, denied using insulting behaviour likely to cause a breach of the peace near the school at Vernon Rise, Kings Cross.

Students R.K., 18, Of Cloyster Wood, Edgware and M. W., 18, of Parsifal Road, Kilburn, were charged with using threatening behaviour and obstructing policemen in the execution of their duty.

S.B., 18, student, of Holmesdale Road, Highgate, charged with W. with obstructing free passage of the highway, was also charged with obstructing a policeman.

They all pleaded not guilty.to all charges.

Protesting

At lunchtime on September 26 over 1000 boys from the school were standing on groups of up to25 being addressed by the “hippies”. Leaflets were being distributed and an 25 being addressed by the “hippies”. Leaflets were being distributed and an an “impromptu play” was being put on “protesting against teaching methods in school”, said counsel.

Chief Supt. M.C. told the court that in plain clothes he joined the crowd. He heard B. tell the boys : “You can take over your school if you want to or burn it down. You don’t need to take any notice of the teachers.”

B. started to argue when told he could be causing an obstruction and so Supt C. said he called for more police. There were eight or nine young men speaking to the boys.

Station Police Sergt. E.S. said he arrested B., who was dressed in a long cloak. He heard B tell the boys: “Don’t let your teachers tell you what to do. You must take over the school and run it yourself.

The boys “cheered and clapped their hands”, he added.

Passers-by who stopped to watch were very annoyed and road traffic was obstructed. When arrested B. called to the boys: “You must not allow him to control you.”

Support

B. Told him : “Go away fuzz. You can’t stop us,” and called to the boys: “Go lads and burn down your school down. We will support you.”

PC J. E.said he heard S. tell the boys: “Taking drugs is good for you”, The boys were getting “very excited”.

An elderly man nearby told S.: “This is disgusting. Go away and leave the boys alone.” He tried to get at S. Who had told the boys: “burn the school down and play football all day.”

When S. was arrested K. shouted to the boys: “Don’t take any notice of him. He is as bad as your teachers. Are we going to let this happen, let’s go and get him back.”

K. Ran into the police station yard followed by a crowd of boys and went for PC Ellis who pushed him away.

PC T.L. said he arrested K who “became violent and was kicking and struggling.” He denied punching him or pulling his hair,” or that he thought it was a “war between the police and hippies”.

PC AJ said he and PC IL helped officers to push the schoolboys out of the police station yard. “They kept coming forward. Other officers arrived and we pushed the boys back. We managed to close the double gates and I secured them with a metal bar.” The boys were shouting: “Let’s get in”, he added.

W., alleged PC I. was “hing himself” bodily at the gates. A numberof the boys became excited and joined him, as W. shouted: “The bastards have got my friends.”

S.B. joined W. at the gates and was shouting through them.

Police Sergt. KN said he heard a clamour and saw a large group of schoolboys milling about and removed a number who were beating on the gates. B and W finally went away across Kings Cross Road

There was a shout and a crowd of boys ran after them and joined them. They completely blocked the footway, yelling and jostling,” he said. He arrested the two men for “obstruction”.

Retired GPO driver Mr. J.E., of Richmond Crescent, Islington said that earlier he heard a hippie tell the schoolboys:”Burn your school down and you can play football all day.”

“I threatened to punch him on the nose.”, he added.

‘Altering’

B. told the court that he and his friends visited schools putting on a play in the streets and urging the pupils that the education system needed “altering”. He denied they were “hippies”.

They handed out leaflets “preaching to the young because it was the best time to influence them”. The pupils were urged to stand up against authority for an eequal relationshyip between teachers and pupils.”

It was a “new form of propaganda”. They wanted “some sort of rebellion” from the pupils to overthrow the existing order of things.”

S. agreed they were “exhorting the boys to overthrow the establishment”. A man who heard him threatened to “punch him on the nose”.

Both he and B. Denied telling the boys to take over or burn the school. S. Said the suggestions came from the boys: “I may have admitted it was a thing they could do, and hang the headmaster.”, he added . “But I said itwould be futile.”

K. Denied in evidence he tried to free S. From arrest and said he tried to leave the yard quietly. He claimed a constable punched him and pulled his hair.

Dismissed

After submissions from defence counsel Mr. DW at the end of the three day case charges against W. And B were dismissed. W. Had been “very excited” and any obstruction was very short, K. Was cleared of threatening behaviour and had been “very upset at S.’s arrest”. He was convicted of obstructing police.

B and S were found guilty as charged.

The magistrate Mr. CB, told them “I have got to protect children, and maybe the whole public, to stop you doing this sort of thing again.

“What you were saying to these children was, to put it mildly, dangerous.”

B. and S. were fined £20 and bound over to be of good behaviour in the sum of £150 for two years. K was condtionally discharged for the same period.

This article consistently attributed words and ideas to us, that the prosecutor claimed we’d expressed, as if we had said them in court.

One thing I remember from that summer was that after the experience of the schools theatre actions, I turned from being inarticulate to becoming much more confident and flowing in my speech. Not permanently, but for a sufficiently long period to make me see that there’s nothing like a bit of consciously chosen history and rebelliousness to release those repressed qualities. Each intervention in each school generated discussions with the kids and amongst ourselves which, although a bit Lefty and militant, were also self-critical and analytical in a dialectical way most people have little experience of. It left a profound mark, a powerful root in my grasp of the world. It gave me a direct concrete understanding about the nature of the cops and of the press, and of the possibility of the breakdown between different youth scenes that technically should have been opposed to one another. Although in the current epoch people have never been so entrenched in their separate scenes, this possibility remains the only vision for a worthwhile future and it’s partly because of this that I’ve thought it worth recounting a bit of that period.

However, the downside of the experience was that I got into political theatre of a less self-educational, more limitedly Agit-Prop kind 18 months later, participating in Bruce Birchall’s Street Theatre projects. In the schools actions, the play wasn’t very interesting but the real life situation it provoked was. In the Notting Hill Theatre Workshop, some of the plays weren’t bad, but it provoked neither interesting discussions nor anything more practical either. All it did, and all it was intended to do, was confirm the local rebel’s experiences of the cops. But then that’s all that theatre can ever do: it can’t advance the consciousness of the participants unless it practically subverts a real situation, as in the schools’ theatre actions. The best thing was the cosy feeling among us the players (though most people got pissed off with Bruce for being very bossy, whilst supposedly criticising bosses in the plays). Also, it was quite funny during the street carnival dressed up in silly cardboard cop helmets, with plastic truncheons, taking the piss out of the real cops, shouting through megaphones “Please beware of people impersonating the police – they are strolling slowly alongside of the procession and can be recognised by their grim miserable faces. You must ignore anything they tell you to do. They are impostors” In fact, in terms of the performances, I have only one memory which is interesting, for me, at least [11] . We were performing a play about the cops we’d written together in a noisy black club in Notting Hill, a club that had constantly been raided by the cops. Throughout most of the performance, a group of blacks, teenagers, were very loudly playing dominoes, banging the pieces hard onto their upstairs table. I’d put together a 3 minute monologue done like Dixon of Dock Green about how sad and pathetic it was to be a cop – “I only arrest someone so as not to be lonely”. The whole place was silent, the domino game had frozen, I had them in the palm of my hand. There’s no punchline to this. It’s just that it’s about the first and last time that I’ve been in this narcissistically flattering limelight in the spectacular theatrical sense. The interest for me is in what it says about the attraction of being the centre of attention, the attraction of the stage, the high you get when everyone’s eyes are on you. Whenever I hear some middle class asshole saying “It must be the worst job in the world being a stand-up comedian” I think of that night. Here I was, still pretty unconfident, but it was easy peasy to get up there and act out a script I’d memorised in front of people who could have booed you off stage. But then, what has spectacular confidence, the confidence of the role, ever had to do with real confidence, the confidence to express your likes and hates directly?

“When I began in the theatre, I thought I was an introvert in a field of extroverts. But they’re all terrified, frightened, insecure people who have found this remarkable outlet of playing all these characters who are not themselves” said Robert Young, a fairly well-known actor of that period. Shirley Booth said, “Acting is a way to overcome your own inhibitions and shyness. The writer creates a strong, confident personality, and that’s what you become – unfortunately, only for the moment.” In a world in which the self is squeezed to the tenuous margin of existence, the desire for the glory of momentary fame is the false exit from this marginality, a seductive trap enticing you with a possible standing ovation. But the flattery of the ego-boost gets you nowhere, keeps you separate and trapped in the circle: you become more insecure and more and more addicted to overcoming this insecurity by the perfection of performance. During this epoch, challenged by the general atmosphere of disrespect for this society, celebrity actors were far more critical of their roles than nowadays. Marlon Brando said round about this time, “Why should anyone care about what any movie star has to say? A movie star is nothing important. Freud, Gandhi, Marx – these people are important. But movie acting is just dull, boring, childish work…”. One might question his list of “important” heroes, but the point is – are there any celebrities who question themselves nowadays? Or take this, from Bette Davis, “What would I tell a young actress starting out today? Take care of your health. Deny yourself fun like you’ll never know. And when you make a picture, you have to say, “This is all I do”. Pretty bloody boring, if you think about it.” This is not to say that celebrities aren’t aware of some aspects of their misery. For instance, the grotesque Graham Norton said recently, “It’s funny that now I’m a success, my life has come to an end. All the stories I have to tell happened before I made it.” And Geri Halliwell recently spoke of how desperately lonely she felt. It’s just that, with the suffocating weight of money terrorism, they are hardly going to begin to even just think about endangering their vast salaries let alone contribute to a movement that could re-start their lives (and ours’).

The only exciting thing connected to the Notting Hill theatre group was when we participated in the subversion of the launching of The Festival Of Light. The Festival Of Light was a collection of religious people and other Guardians of Morality, like Cliff Richard, Mary Whitehouse (the clean-up TV campaigner), Malcolm Muggeridge (a Catholic journalist/media pundit, a favourite for schoolboy impressionists because he was so ponderously pompous, had weird upper class mannerisms and facial expressions and a corny upper class accent), and others I can’t remember. The whole disruption was well worked out. A delegate from each little group met up and each told everyone what they were going to do and everyone had to just remember the action they would come after – say after the screaming monks or whatever. Someone had managed to get hold of tickets, or maybe they were forged. We go in – TV cameras are there. Most of our group dress smart conventional and claim to be Wimbledon Young Conservatives. Our act is to rabidly cheer the stage [12] . Bit by bit people do funny things: a guy goes to the front of the audience and just below the stage slowly takes his clothes off; some nuns start to very ostentatiously snog and grope each other – this, in a large hall – Central Hall Westminster – with probably at least 50 real nuns, and hundreds of Christians of various kinds; a large group hang over the balcony a large sign with Cliff Richard’s secret gay name (Gordie?..can’t really remember) – Cliff Richard goes bright red. Someone shouts to Malcolm Muggeridge, “What do you think of homosexuals?”. He replies in his usual constipated and contorted manner, his repressed way of oozing self-righteousness, “I don’t like them”. Because I’m meant to be from the Wimbledon Young Conservatives I shout out, in my poshest accent, “Hang them! Hang them!”. The guy next to me, who’s a genuine Festival of Light supporter and with whom I’d chatted before in my ridiculous Young Conservative role, says to me in a lightly admonishing sort of way, “That’s not a very Christian attitude”. Various things are going off – people are dancing erotically, others are shouting, us we’re cheering a lot and often for a lot longer than any of the rest of the audience, and the chair woman tells us to hold our enthusiasm till the end of the speech. The guy next to me turns and says, “Look over there – they’re going to do something next, I’m sure of it.” I feel a little nervous and embarrassed for him – any moment now he’s going to find out I’m not on his side and it’s going to be a little shock as we go into our not-so-Grand Finale. We continue cheering for a hell of a lot longer than anyone else (and there are only 8 of us) and the chairlady at the mike on the stage says, “We appreciate your enthusiasm but would you kindly refrain from indulging it excessively” or something like that, and so we then jump out of our seats and rush towards the stage, rattling football rattles and blowing plastic horns and kazoos. Security grab us and chuck us out. Me and this woman in our group go round another entrance and say, still in role, to the guy at the door something like “This is appalling – we got mistaken for troublemakers because we were in the same row as them, and we got kicked out. There’s been a dreadful mistake!”. He lets us in. People are throwing leaflets around from the balcony, the place is fairly chaotic. The woman I’m with and me get up and run up the aisle arm in arm shouting, “Fuck for Jesus! Fuck for Jesus!”. Security grab us and kick us out properly this time. On the telly afterwards it was just described as a load of hecklers disrupting the launch meeting – none of the inventiveness was mentioned.

This was an epoch when there was a far greater margin of freedom from money worries and work than nowadays, in which the fight against hunger had been superseded by the fight against boredom. Money madness hadn’t taken over because the working class were on the offensive – strikes defeated the governments’ attempts to rein in the wildcat strikes in 1969 – and much of this offensive was as much to do with fighting boredom as asserting dignity and solidarity.. In writing about this past, the aim in some way is to sharpen the contrast between then and now so as to incite a return of the repressed, a return in very very different conditions. The epoch won’t return like that of course. At that time, revolution was fun, but not very serious. If there is to be a future revolution, it’ll be born out of very desperate conditions. There will be fun and pleasure, for sure, but much of it’ll be agony, bitter and above all, the desire for fun will be very very serious.

March 2001 (some bits added 2004)

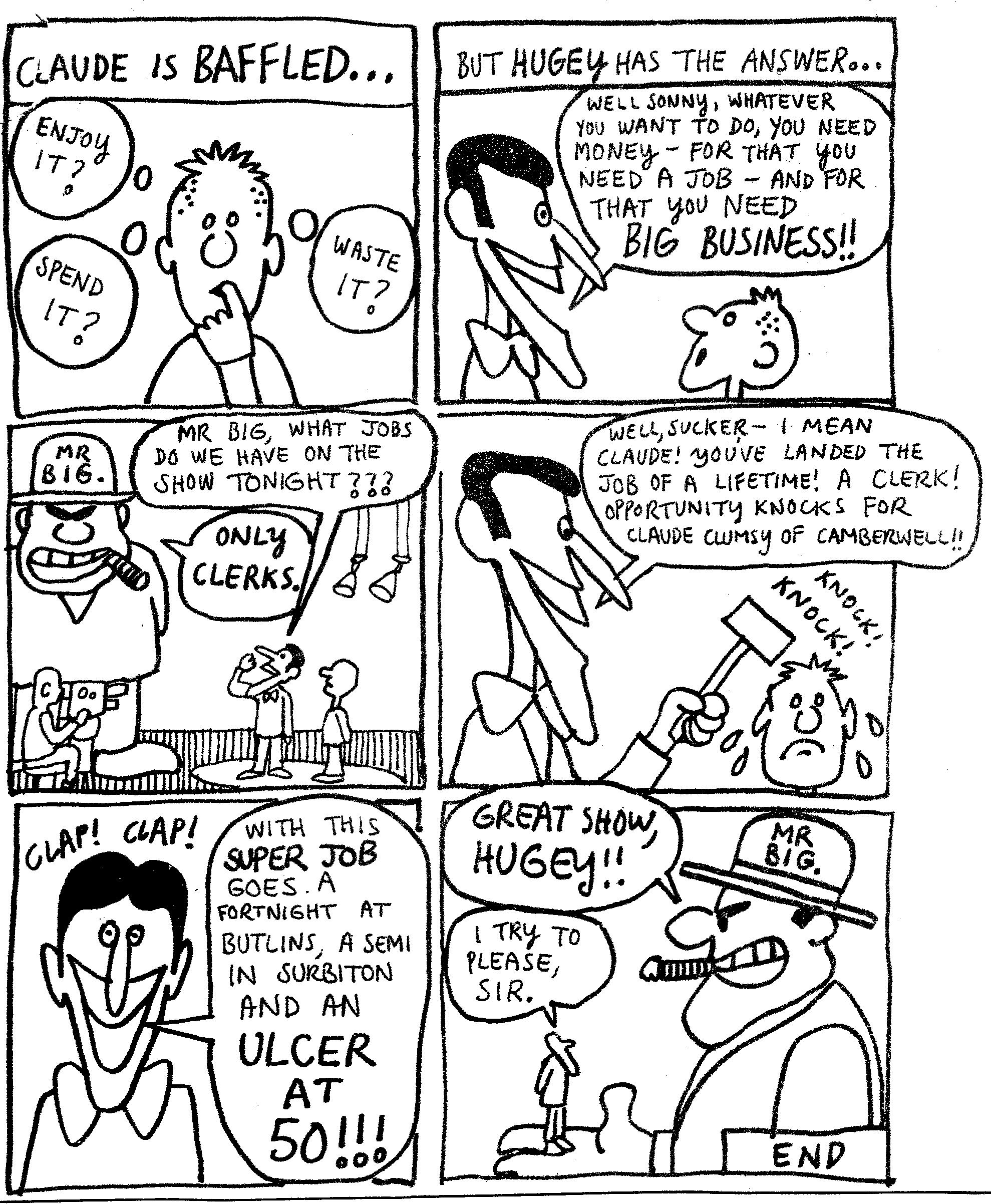

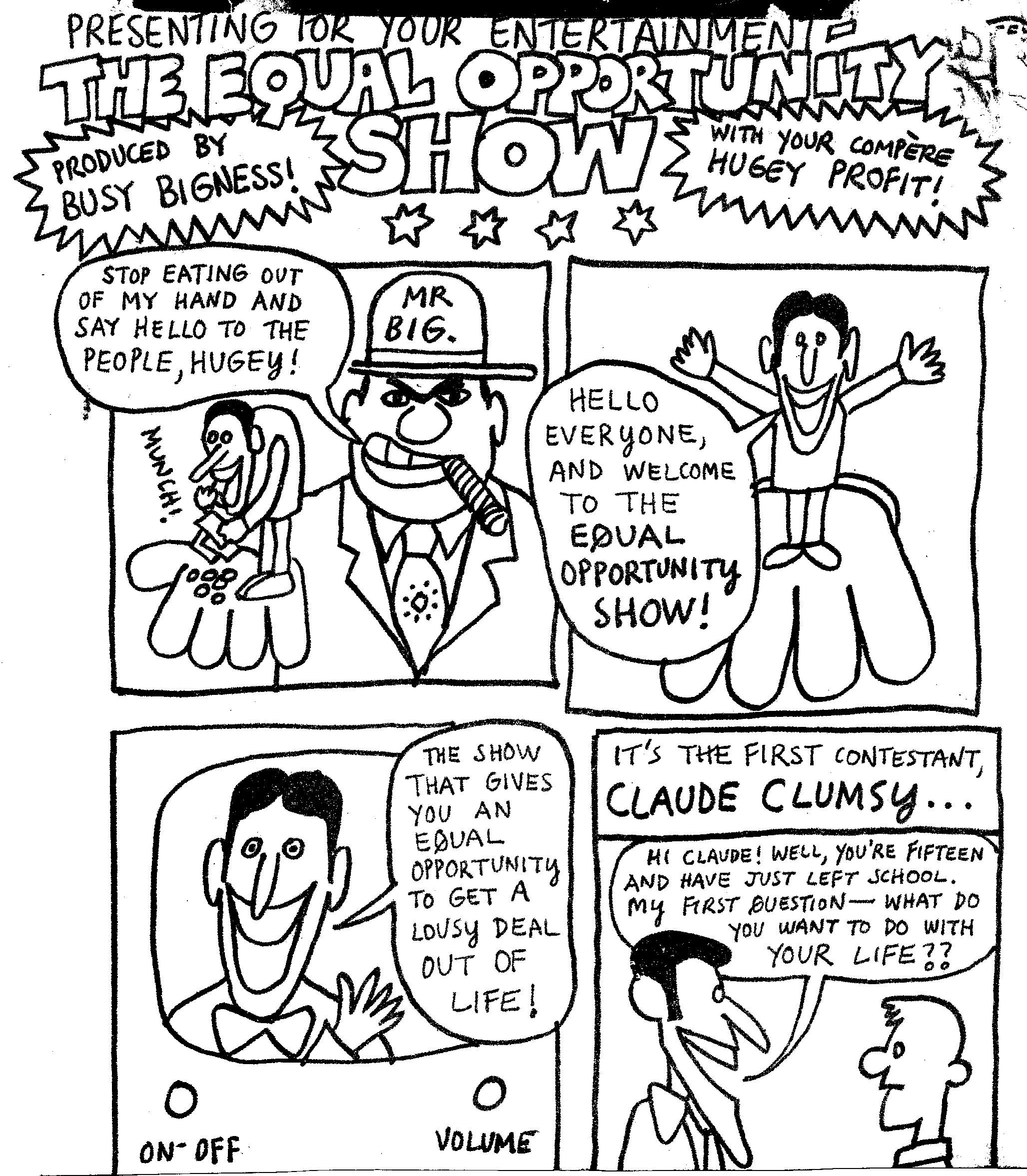

This was a leaflet for a show (drawn by Irish, formerly of King Mob) on work and unemployment which I helped produce along with others in the Notting Hill Theatre Workshop back in 1971 or 1972.

This was a leaflet for a show (drawn by Irish, formerly of King Mob) on work and unemployment which I helped produce along with others in the Notting Hill Theatre Workshop back in 1971 or 1972.

FOOTNOTES

1 He didn’t really like the rather hack, Lefty tub-thumping aspects of Brecht, but not from a radical angle, more from an ‘art for art’s sake’ perspective, which tended to dsimiss any sense of purpose. He’d known Brecht a bit, mainly through Brecht’s wife who was a friend. I guess they’d met during his acting days in Berlin, before he left in 1933. It’s well known that when the steelworkers rose up in East Berlin in 1953 and went to Brecht’s theatre to ask for help in supporting them he refused. What’s not well known is what my dad told me about him: he felt so guilty and ashamed after the steelworkers were crushed by the tanks of the Stalinist leader, Ulbricht, that his health suffered, and it led to his death in 1956, at the age of 58. If nothing else, this shows how a culture of proletarian subversion usually has nothing to do with its practice, and that those who consider ideas as something separate from real life risk are at best useless when it comes to any genuine struggle against this world. Fear had nothing to do with his failure to support the steelworkers: Brecht’s international reputation put him in the unique position of having nothing much to worry about. His only response to the uprising was to write a brief poem after it was all over -The Solution – which, though written in verse form, I reproduce here as a statement,because the verse form adds nothing to it: “After the uprising of the 17th June, the Secretary of the Writers Union had leaflets distributed in the Stalinallee stating that the people had forfeited the confidence of the government and could win it back only by redoubled efforts. Would it not be easier in that case for the government to dissolve the people and elect another?”. Neatly put, but too little too late, and no use in stemming that dreadful feeling of self-betrayal, betrayal of everything he’d apparently held dear to him, that must have torn and worn away at him until death.

2 Later I could see the stupid and arrogant side of Daniel Cohn-Bendit’s role in May ’68 – as mouthpiece/spokesman for a movement whose most radical tendencies were a refusal of representation; in it was the germ of a sickening political career which eventually led him to support, as a deputy in Germany’s Parliament, NATO’s bombing of Yugoslavia and Kosovo. Recently he got heckled when he appeared advocating a OUI vote in the constitutional referendum on a platform with the leader of the French Socialist Party. In an interview he blithely shrugged off criticism with an indifferently cynical, “Well, I’ve been betraying myself all my life…”

3

The term sticks in my throat a bit, though it was constantly used at the time (and still is sometimes). It’s the leftist equivalent of ‘business partner’ or ‘colleague’, so formal and stiff. Above all, it’s specialist, separating politico relationships from friendships. It also sounds a bit militaristic – soldiers often call each other ‘comrades’. It also has corny Stalinist connotations, like those nasty Reds in cold war spy movies. However, it seems sometimes necessary – how else can one refer to people who aren’t exactly friends but are on your side in a fight with authority?

4 He ended up teaching sociology – concentrating on marginal groups – to Police Recruits, and now is Professor of Cultural Studies, teaching psychologists about yoof. Nice guy (not).

5 She ended up doing Ken Loach-type tv shows, like Days of Hope, about the General Strike of 1926. A month back I half-listened to a totally uncritical, and boring, radio play by her about a woman who starts a business on the Internet, gets American funding and leaves her husband for her American backer, a glaring example of how irrelevant the political content of a piece of fiction is – once you specialise in a particular form, the content is just a matter of adjustment to what might be popular in any particular epoch. If there’s a significant social movement anytime in the future in this country doubtless it will be accompanied by those who specialise in representing it in dramatic form. Such a movement will have to attack these recuperators from the start if it’s going to advance.

6 Muldoon was the most famous purveyor of Street Theatre, having started it before 1968, his group usually performing on demos, classic hammering-home-the message stuff, self-consciously so since it called itself Cartoon Archetypal Slogan Theatre. Once, whilst waiting for Pam Brighton to finish the theatre group’s meeting , he told me in a gratuitously aggressive bossy way, to get out, because my silent and still presence was distracting him. Classic theatre director/prima donna style. Classic keep outsiders outside gang boss mentality. At a performance in a polytechnic CAST, Muldoon’s group, got heckled towards the end of their play, partly just from a situationist-type perspective – for being a theatre group. The actors exploded defensively – “We’re into excellence!”, one of them shouted arrogantly, sounding a bit like an Ofsted inspector. The last I heard of Muldoon was that he ‘d managed to get loads of celebrities to help raise £15m to renovate the Hackney Empire. He recently said “We always shared a mission to try to bring good theatre to the working class”. If he’d said it with a middle class accent it would have shown up his patronising absurdity but because he’s got a cockney accent he sounds superficially working class and certainly a guy who knows the business – so he can get away with it – people just nod and smile. Let’s hope that at least he’s lost all pretensions to any radical content. Let’s hope that one day he’ll end up like another missionary position that’s fun – that one in classic cartoons – the missionary in a large pot surrounded by us savages.

In 1970 in ‘Radical Arts’, John Barker, later of Angry Brigade fame, wrote the following interesting take on CAST: “The most acute of ‘liberatory’ theatre is CAST going around from university to university ending their shows by smashing some property. This is complete substitution. The Who similarly with their guitars. The audience expects it, wants it to happen itself , but is frightened to do so. Whereas CAST have the artists prerogative to do it. This is the most acute case of the classic ‘alienation’ which art can afford. We contemplate other people destroying the environment we want to destroy”.

7The leaflet was as follows (the underlined bits in it were the words of the song we sang during the song ‘n’ dance routine in the play, to the tune of the Hokey-Kokey song):

YOU PUMP YOUR FACTS STRAIGHT IN

We are all forced to memorise thousands of dull, meaningless facts. They decide what and how we learn!

YOU TAKE YOUR QUESTIONS OUT

We always have to answer their questions (in tests, exercises, homework, mocks, exams) – never question their answers!

YOU TAKE YOUR YOUNG MINDS AND YOU TWIST THEM ALL ABOUT

We are all moulded to think the same, act the same, dress the same – be the same. Authority and fear are used to keep us down, to crush our own personality and our own ideas, to make us obey blindly and without thought!

YOU GIVE THEM COMPETITION SO THEY HATE ONE ANOTHER

They say that to be successful we must compete against each other. So knowledge becomes a possession not to be shared, but to be jealously guarded, making us mean and isolated. We begin to accept the school’s judgement of our friends (“You’ve only got 3 ‘O’ levels!!! Heee!)!

SO IT’S COMPETITION FOR EXAMINATION – YES THAT’S EDUCATION

Exams are an endless series of hurdles – a race to acquire a better position at the expense of those who fail. They cause fear and worry; the rigid sylabus prevents wider learning and they waste a great deal of time. They govern the whole of our education!

* * * * * *

The same situation continues beyond the school-gates. Just like school, the outside world, through its newspapers, its radio, its

advertising (all in the hands of the few) moulds our minds to accept its values. Just like school, the outside world forces us to obey,

without allowing us control over the decisions that affect us!

We believe that in school, as everywhere else, the authorities must be attacked and questioned on every level.

We believe that education should be based on co-operation, not competition – working with people – not against them!

Me and another guy who I’d got nicked with wrote “From Guerilla Theatre to Courtroom Farce”, available on this site>

8 Now, I think, well, why not? – but reading back on the text I later wrote with one of us there’s a lot of resentment towards kids who weren’t playing their role of respectful audience; sure, in St.Paul’s their motivation was clearly different from that of kids in other schools – the fact that the guy with the longest hair had water poured over him is indicative of their mentality. Nevertheless, the disdainful contempt for a naughty audience who hadn’t been asked if they wanted to watch was a typical symptom of our attachment to our Middle class ‘educative’ role, our belief that here was a play worth being respectful of, and anyone who didn’t show respect by their “predictable puerile comments and antics” was just a nihilist philistine. Sure, that’s fairly exaggerated but it was a tendency; the other tendency being that we were the ones getting an education (later that year, on November 5th, some people, including Barker and Greenfield, were going to do a play of the People’s Trial of a particularly hated cop in the Notting Hill area; they had a model of the cop and of a judge, whom they were going to dump on the fire after they’d finished the play but the kids, who really hated this particular cop, grabbed the papier mache models and dumped them on the fire before the play could begin; the performers were a little annoyed, but obviously let it go, after all, if you get too attached to the role of performer you’ve lost the point.