“A prisoner who cannot see the sky from his cell window may paint on his wall a scene of birds flying amongst clouds against a blue haze of space. Outside in the wider society art plays a similar role; what is denied and seems unreachable, but possible and desirable, is represented via the window of the picture frame or TV screen.”

Updated with some minor alterations to sharpen and clarify some of the content: March 2006

![]()

The Decorative, The Functional &The Ugly

Ultra-Left On The Shelf

Art Therapy?

Culture & Daily Life

Gone With The Wind-Up

Interpreting The Interpreters

Don’t Say Art – Say “How Much?”

Taste & Tasteability: Taste Modern (& Ancient)

The Urge To Destroy Is A Creative Urge

A comment on the attack on Duchamp’s “Fountain”

![]()

A prisoner who cannot see the sky from his cell window may paint on his wall a scene of birds flying amongst clouds against a blue haze of space. Outside in the wider society art plays a similar role; what is denied and seems unreachable, but possible and desirable, is represented via the window of the picture frame or TV screen. So art/culture as the representation of what is repressed fuses with the commodity form; the very form whose domination has fragmented this creativity from the rest of life.

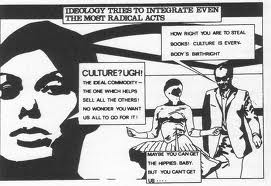

And with this fusion adverts become seen as “the cutting edge of art”. Advertising is essentially advertising the positive qualitites of the whole of the commodity system – not just a particular product, whose increased sales as a result of advertising isn’t as socially important as the fact that what advertising sells above all is this society. The ‘witty’, ‘inventive’, ‘imaginative’ artistic permutations of advertising excuse its fundamental cover-up of a brutal system. The progress of advertising is the inevitable result of art and the best indicator of art’s fundamental stupidity, a far more positive collaboration with this shit world than anyone who isn’t officially ‘creative’, apart from politicians and big businessmen. The fact, for example, that surrealism has been part of advertising for over 30 years shows the poverty of even the best art.

The contradiction within art is that it appeals to our desire for realisation of what it represents – passion, creativity and other experience routinely denied in bourgeois society – but it only “realises” in a fragmented, isolated manner, separate from daily life. It is now art and the cultural spectacle, not religion, that is “the opium of the people” and “the heart of a heartless world”. The art of an artless life. This is why, wherever circumstances allow, religion also organises itself in the image of the latest media technology – from slickly marketed TV evangelism to increasingly theatrical church services, Islamic TV and radio stations etc[1]

The critique of culture follows on from the critiques of religion and of philosophy; all are separations and divisions of labour that emerge with new developments in class relations.

By culture [2] here we mean its skills and arts that emerge with the development of class society and have always tended to encourage a division between professional specialist performers and passive spectator consumers – as in sport and the arts. We say tended to because culture wasn’t always as clearly defined a separation as this – especially what is now retrospectively categorised as ‘culture’ amongst previous poor sections of society in earlier epochs. [3]

In saying that religion, philosophy and culture are separations coming from the hierarchical division of labour we cannot deny some sometimes excellent qualities expressed in these forms but to recognise also their fundamental limitations and weaknesses, miseries and even horrors (e.g. Greek philosophy was born in a slave society which the philosophers, for the most part, accepted without question; and dominant culture has always justified the horrors of class society, racism being one of the more obvious aspects of this culture). Religion is linked to the development of social hierarchy in early human society and the appearance of a division within the communal life where a representative caste of priests emerges to mediate between gods and society, sometimes including the aestheticisation of human sacrifice. Art appears linked to the development of magic, ritual and tools as society develops new relationships to the rest of nature. Before this, in tribal societies, there was no separate sphere called ‘art’ or ‘culture’: these activities were originally integrated into the totality of people’s social relationships and their relationships with nature. But as class society develops, the fruits of exploitation flow to the rulers and create a class with a surplus of leisure time and resources to produce and create in non-essential activities – and so aesthetics develops as a specialised practice of both production (artistic creativity) and consumption (appreciation). The same occurs with the production of ideas and other intellectual processes, leading to philosophy.

* * *

“Culture is still the location of the search for lost unity, but in this search, culture as a separate sphere has been obliged, in part, to negate itself. Each person contemplates not only objects and images, but also the aesthetic totality that he has made out of his daily life. Personality is the new artistic medium”

– Chris Shutes, “Poverty of Berkeley Life”, 1983.

The fact that many forms of creativity have nothing directly to do with making money does not in itself mean that they are automatically non-hierarchical, nor that they are not products of externally defined, ultimately economically defined, notions of what creativity is. Whilst a degree of specialised effort and experience might be necessary to play a musical instrument or create something that looks nice, it is when such specialisations are seen as something to be put on a pedestal, something that makes you separate, a role, that they lose all desire for the kind of sociable communicative creativity that we find enjoyable. I knew someone who refused museum culture and had a critique of art-as-commodity but created some attractive visual art works not for sale (at least, not yet); he made slides of them and had them projected onto his wall, constantly changing during a party he gave, to the point where it was difficult to hold a conversation, the large visual display as distracting as a widescreen TV, and the loud techno music adding to the difficulty of talking. The fetishisation of this particular form of ‘creativity’ dominates not directly as an economic force but still debilitating.

Likewise, there are those who consider themselves best qualified to play a musical instrument and sing at parties, who resent others trying to play or sing because they are not so specialised, not so good at it, even though the communal joining in of singing and playing and drumming and dancing is far more pleasant, even if not ‘expert’, than the very best performance held in reverence. Taking your specialism too seriously solidifies a hierarchical judgement of individuals in terms of their ability, or lack of it, to express themselves within the narrow criteria of creativity defined in terms of their specialism. But everyone drunkenly singing loudly along to silly disco songs slightly out of tune is far more fun than a stiff appreciation of a really good musician.

Precisely because the ideology of creativity justifies almost everything, it is very common for the artistic milieu, despite the pretension to being something better than ‘business’, to blur the distinction between friendship and economics, often functionalising people for their connections and money outside of work-defined contexts (networking at parties, for example)[8]: after all, it helps the ‘creative process’. The specialisation process often appears to be something outside of money-making, developed in the specialists’ leisure hours, though it is also often necessitated by the possible option of making future money out of this creativity. Which is somehow regarded as something natural, inevitable. Obviously we have nothing against people making money out of music or some other “artistic” form of alienated labour – depending on where they are in the social hierarchy; but it’s the illusion of ‘creativity’ and the resignation to their specialism (they only come alive when they’re performing) that make communication and the totality of social relations amongst artists so utterly conventional nowadays. For example, street performers who pursue the mirage of making it, whilst contemptuous of those further down in the hierarchy – e.g. the beggars who never ‘create’ anything, who ‘give’ nothing for their money (when often the ‘creative’ buskers – whether of music or some other performance, say a slow motion mime artist, can be just as easily as irritating as, or worse than, a beggar)[9].

* * * *

The ‘wind-up’ is an example of turning miserable social relations into a work of (performance) art. Though economics had no direct reason for its development, it’s ‘spontaneous’ expression coincided, in the mid-80s, with the intensified repression of class struggle. Before these defeats, the wind-up (including the practical joke) was usually used either against some of those in authority, those too submissive to authority, the most moronicly naive or just against someone who behaved in a persistently annoying way. It had a conscious target, a point. From the 80s on it bit by bit it became indiscriminate who you wound up, an aestheticisation of the war of each against all. This had always been around but at this time it became a particularly humiliating form of ‘creative play’. Having lost the anti-hierarchical reason for this originally subversive game, targetted at the right enemies, the increasing defeat of the class struggle turned the wind-up inwards – democratic, applied arbitrarily and equivalently everywhere whether against potential friend or obvious foe, the aim being not to change things but to make the victim feel very stupid and the victimiser feel very clever and very smug. Everyone their own Jeremy Beadle. The arbitrary spread of computer viruses is a particularly specialised part of this haphazard wind-up culture, turned even more alien through the relative safety of internet anonymity. Or a fairly recent commodity in which you pay for some pre-scripted put-down read out by the celebrity of your choice, which is sent as a mini-video to the mobile phone of the partner you’ve decided to break off with, a parting gift: no need to even say it to their face. An impersonal ‘creativity’: makes a Ukranian winter seem like a summer on the Riviera in comparison.

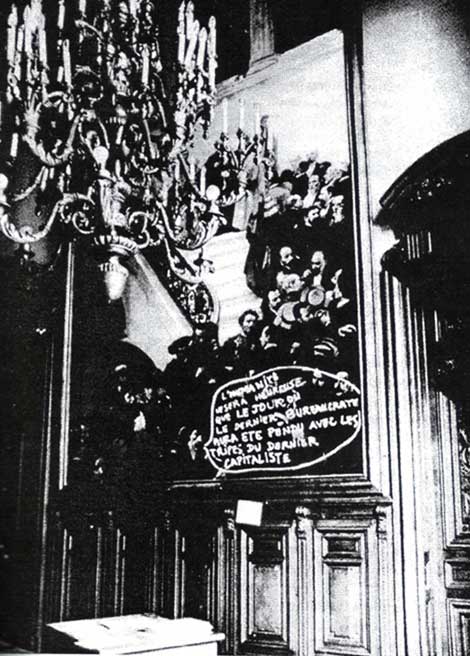

It’s vital to emphasise that within cultural forms (just as within religious forms in pre-capitalist times) there has always been a revolt against the existing order – Blake, the Romantics, the Dadaists, etc. etc. However, until the experimental projects of the Situationists in the decade before 1968, these movements never pointed to the way out of the art impasse: they remained trapped within the the prison of art. What was original about the Situationists was that the most radical theoretical critique of society up till then was developed from a critique of culture and of art. Coming from the avant-garde of art, the Situationists negated their own positions as cultural specialists in order to attack, with more coherence, the presuppositions of culture, and by extension, the entire social system whose very basis is the representation of life opposing itself to life. This they called “the realisation and suppression of art”. In other words, struggling to realise, in the world around us, what was a separate and purely imaginary creativity , whilst suppressing art as a separate specialism. The recognition that the totality of life could be creative if we destroyed the commodity form, in which the spectacle of creativity is now inextricably a part, coincided, in the late 60s, with a massive assault on class society which gave a massively practical meaning to what initially had seemed like some wierd esoteric intellectually nihilist idea. The desire for scandal, which radical art has always expressed, realised itself in the most scandalous desire of all – the mass threat in May ’68 to the essential repressers of genuine creativity, the State and the Economy

Since then, to participate in Art has clearly been a way of bringing in as much money for the least effort as possible, an economic scam – and its pretension to originality has overtlymerely been a marketing ploy. Hence, as a way of trying to hide this fundamental poverty, the enormous boom in the art interpretation business in the last 20 years – those endless ‘radical’ etc. interpretations of something that a 6 year old would put more energy and thought into.

(graffiti in the Sorbonne, May 1968)

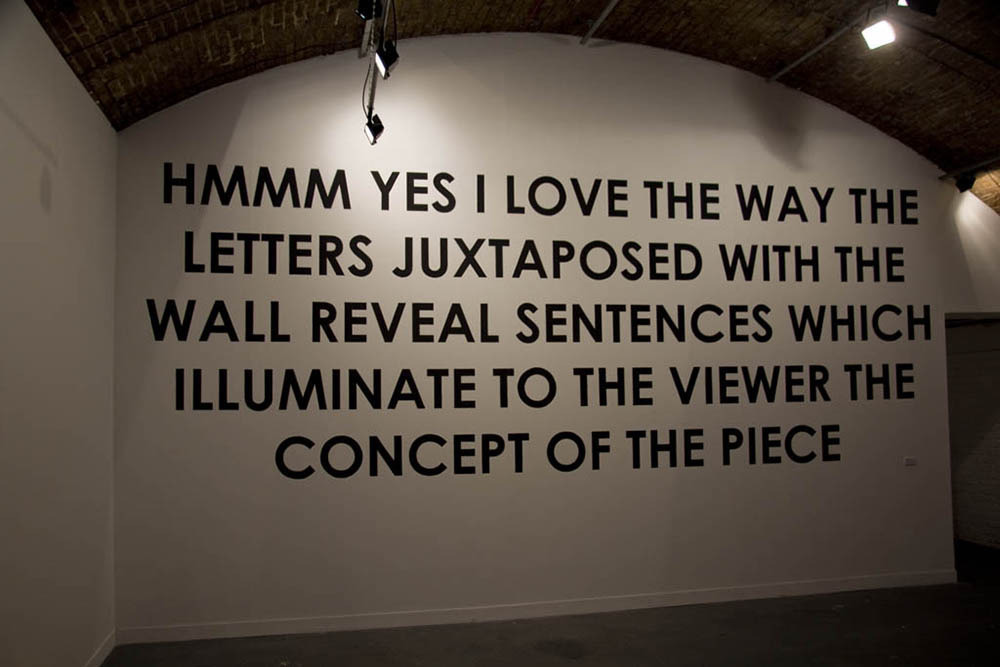

The less intrinsic quality there is in an art commodity, the more the interpretation has to convince the public that the Art Emperor has the most interesting clothes that clarify the false dichotomy expressed within the feminisation of structural dysfunctionality on the juxtaposed dissonance of extraneous modernity dissembling its ironic pre-tonal pretext within a critical distanciation from the original hypothesis bla bla bla. The ‘qualities ‘ of an artwork exist only in the interpretation of it; in this way it can be made to mean anything you want it to mean. It’s like advertising for intellectuals: to give ‘meaning’ to a meaningless product in such a way as to make you think yourself more special than those who are conned by banal TV adverts. And it increases the investment value.

The more you interpret some banal piece of art as significant, radical, original, or whatever the more you can convince yourself that you are significant, radical or original by valorising the significance, radicality and originality of your taste (as consumer) or of your creativity (as producer). This is not a struggle to understand the world, life, and culture by trying to change and subvert them, to question everything about them, but a purely passive interpretation, like philosophy. Yet, the more verbal or written interpretation you produce the more you can convince yourself that you’re not merely passive in relation to the artwork. Repressing all critical disgust, approving interpretations of some installation or whatever and valorisation of its innovative qualities is a way of showing yourself as an interesting creative person, a way of selling yourself, your personality, a way of proving how ‘modern’ you are. It’s an aestheticisation of the intellect, a philosophising not to change things but to magically turn your passivity before a work of art into a positive influence. But all that changes are your undoubting thoughts and the possiblity of valorising yourself through them.

In essence, all of these approving ‘interpretations’ have one basic statement: “Very few people understand what this is all about.” The fact that only the very clever, the sophisticated, esoteric and intellectual, can offer an apparently clear interpretation adds to the rarity value, to the investment value. In an art world of High Finance, specialisation of interpretation is part of “you scratch my specialism and I’ll scratch yours”. Inevitably, in such a narrow circle, the poverty of this art is hidden by the monetary value of it, interpreting their art all the way to the bank. In a world dominated by fictitious capital, art is as much a con as false accounting.

Parodies of these absurd interpretations have been around since the end of the 1950s. Though the content of the parody has to change to keep up with the times, parody, though often very funny, is also a way of minimising the repulsive social relations behind the pretensions of the interpreters, the professional “critics”. That’s usually because those doing the parody have similar social relations utterly complicit with the repulsive world hiding behind these pretensions, jokey or otherwise.

Doubtless one day, some ironic post-modernist recuperator will read this and be inspired to produce canvasses on which long interpretations are painted. Or better still, a large canvas on which is written “Very few people understand what this is all about” or “We’re taking the piss” whilst the catalogue won’t have any words but instead some small photos of a bag of mouldy doughnuts, a dead rat, a pool of vomit, cops in a car or whatever. Maybe it’s even already been done.

above added 26/8/15

Don’t Say “Art”, Say “How Much?”

In the context of a market economy, the artwork is the commodification of meaning, statement and expression – embodying them in a saleable object or activity, the name of the producer, and the interpetative ideology that goes with them adding or detracting from its value/price. Art is the domain of the “uniquely creative” specialist, the glorification of the hierarchical social division of labour. But to fetishise the uniqueness of one’s own subjectivity is only to recognise its demise – we are all now products of a uniform age of uniform experiences[10] – so the artist has to push the limits of his/her extremism ever further to make any impression on the jaded consumer: witness the recent exhibitions involving the public vivisection of corpses in UK art galleries and the performance of the actual eating of dead babies by Chinese artists [11]– confirming that though art may be dead it won’t stop some consuming its corpse.

At the same time there is a popular disgust for the modern art con which nevertheless never gets to grips with the art it criticises and so ends up just being a superficial battle over taste. This is exemplified by the former Arts Minister Kim Howells’ denunciation of “conceptual bullshit”. It just leads to a petty reform of the Art spectacle – e.g. the obnoxious Saatchi’s decision to exhibit……horror shock….paintings painted with paint on canvas within a rectangular frame!!! – “The Triumph Of Painting” he’s going to call it. Or the shock that last May’s shortlist for the Turner prize contained not one single bit of shock art. So we see a demand for the return of something like the Old Masters, who developed their skill over years and years of dedication and effort and imagination and talent and genius (and, usually, massive unacknowledged plagiarism which they then made a bundle out of ) in reaction to the hype of sharks in formaldehyde, unmade beds and endless attempts to horrify (which lost most of their scandalous power before these artists were even born). This popular disgust wants its art elitist – not something anybody could do, and certainly not something they could do (if they didn’t have to lick so much arse to make money doing it, at least). They want a better spectacle of other people’s creativity – a new Goya or Van Gogh [12]– something to lighten up their lives or move them in some way, something to make them feel sophisticated in their taste, that they are people of quality because they appreciate things of quality.

Exchanging ones different tastes, arguing about what one likes and doesn’t like about this or that different bit of culture is one of the most common forms of interaction nowadays. Most of what passes for criticism of this or that cultural thing is merely a battle of egos, a pointless exercise in my taste’s better than yours’: a pretty petty way of judging individuals. Kenneth Clarke, the former Tory Chancellor, likes Charlie Parker. Adolf Hitler was a vegetarian. We too like Charlie Parker and vegetables – but this is hardly the point. When attacked for ones taste, it’s fine to defend it, to not be made to feel ‘incorrect’ and guilty about pursuing it – but there’s a lot more fundamentally meaningful, critical, things to be said about cultural consumption. And when some people say some movie or commodified piece of music is more radical or more fascist than another, simply on the level of their immediate content, that says very little.Above all, it is the taste for adventure, for experiment, for progress, that is repressed by arrogant battles over consumer tastes. In the commodity economy, “adventure”, “experiment” and “progress” is permitted only in the form of a merely monetary measurability; “adventure” becomes a business risk, “experiment” becomes “let’s try this new marketing ploy”, “progress” becomes “I’ve made more money this year than last”. Or, at best, they’re seen in terms of your leisure time: “adventure” becomes sky diving or some other extreme sport, “experiment” becomes “let’s go somewhere new”, “progress” becomes “I can play pool better this year than last” – which are ok but are defined narrowly and, like all leisure activites, have no social consequence – they’re not adventures, experiments or progress in social relations. Heated arguments over consumer taste try to obscure this fundamental misery whilst avoiding more profound adventures & experiments and the realisation that, far from progressing, we’re increasingly regressing. In this ever-narrowing cynical world based on defeat, asserting ones consumer taste seems a way of breaking out of this narrowness and defeat, apparently asserting ones personality, oneself, because asserting ourselves in any more experimental way seems like too much of a risk.

Taste is not the important thing – it’s the social relations that come from the fetishism of cultural commodities and the way, within different epochs both historical and personal, creativity and communication is destroyed or enhanced by ‘cultural’ forms that’s important. It’s these fundamentals that are the essential basis for understanding and judging culture. So when we say we don’t like Salvador Dali or John Lennon for instance, it’s nothing to do with whether or not we like their pictures or their music.

In a world where morality is increasingly recognised as hypocritical and petrified, taste becomes an alternative, more fluid, less crude, more subjective way of asserting ones ‘essential’ superiority. Whereas morality was repressive, taste seems to be expressive. Although some search for a personal meaning seems to be expressed in terms of taste, taste is ultimately a sad consolation for not being able to really be creative oneself. Taste only seems to be expressive – it never gets beyond being a background commentary to the gaping wound at the heart of daily life. Taste is like a comment on the bandage covering that wound – what a wonderful pattern the blood stain makes. Taste gives the illusion of not being passive – yet it’s as much flowing with the tide as talking about what you’ve seen on the news. Whilst mostly unavoidable, it’s not a search for a way out of passivity. And in the end, cultural taste becomes a hierarchical battle, a subjective justification for the objective division of labour, a notion of superiority every bit as evasive and invasive as morality, a distortion of desire as destructive of the individual as morality.

Many of those consumers of art who get into taste fights often ahistorically mix up everybody who produced Great Works Of Art. For them, it’s as if all epochs blurred into one and Creative Genius, at least in the visual arts, manifested its quality through a few rare individuals with some ‘eternal’ ability existing outside of historical influences. As if, in other words, one could somehow produce paintings as good as a Goya or a Van Gogh or an Henri Rousseau today and we could all admire them. As if the passions that inspired former artists in former epochs could somehow arise within the all-pervasive repressions of existing society. This is certainly not to say that 19th century/early 20th century capitalism wasn’t also very claustrophobic. But at that time, if one made a break with aspects of it in some way, the greater extent to which life was not invaded by externally defined ‘imaginative’ forms enabled you to still express yourself with some originality and uniqueness within art. Nowadays, accepting these forms is already a denial of any authentic passions because these forms colonise us like never before. ‘Originality’ expresses nothing heart-felt, human or individual because people hardly have any heart or humanity or individuality. Originality’s just a novelty designed to distract, to impress with its overwhelming monumental power, to be different for the sake of superficial entertainment. A true opposition to the horror that Modern Art has become can only use the inspiration of the past by looking at how these passions failed to develop so as to find a way through to expressing the life and experiment there used to be in art. The specialisation in creating aesthetic objects didn’t always hide the ugly world around us, but expressed a desire, and was often nurtured in the struggle, to somehow supercede this world; likewise (but differently) the later specialisation in creating ‘ugly’ objects (by Man Ray, Duchamp, etc.) was originally an attack, first developed during the horrors of World War I, on the same decomposing world which now makes such ‘shock’ tactics so profitable. It is only on the basis of recognising these failures that one can get beyond the superficial battles over taste, beyond good and evil, and recognise what was a truly radical desire in both previous Modern Art experiments as well as – in their different ways – in Munch, Rousseau, Van Gogh, Turner, Blake, Goya and thousands of others. At the same time, there’s often an unhealthy servile respect for these ‘greats’ which puts them on a pedestal utterly above – and certainly nothing like – our own lives. People ignore what was uncreative in the lives of the ‘greats’, as well as diminishing what was or is creative, or potentially so, in their own lives. This excessively self-effacing, admiring and adoring attitude refuses to recognise some aspects of the contradictions of the greats in their own history of creativity and destructivity and the history of people they know and have known.

All these different forms and content of art through different historical periods have now been turned into different share prices on the investment scale. Art has very clearly become what Shakespeare said of gold – “Gold…will make black, white; foul, fair; wrong, right; base, noble; old, young; coward, valiant” (Timon of Athens). Art is just an equivalent, an exchange value – it excuses all its own horrors and idiocies. It is this disgust for what art has become over the last 70 years that anyone with any integrity has rightly realised is something beyond the taste battle – it’s an essential moment of discovering the possibility of creative destruction everywhere.

The Urge To Destroy Is A Creative Urge

In the upside down world which makes dead labour worth millions more than living labour, the destruction of a Rembrandt or of the Mona Lisa, like in the picture at the start of this text, would receive a million more headlines than the death of someone unnecessarily freezing, which is a banality. Sure, the image of the destruction of the Mona Lisa that we put here could, and probably already is, used in some corny anti-art framework: the art of the “destruction” of art (now, putting Damien Hirst in a tank of formaldehyde would be a genuine anti-artistic innovation, at least if he were alive before work on such a creative act began). Less likely is the use of Da Vinci’s painting on the front of a barricade, a version of what Bakunin had suggested in the Dresden uprising of 1849 – to delay the advancing armies of the State and save the lives of insurgents. In May ’68 the Louvre was never attacked. But you could have been sure, the accusation of philistinism, not to say derangement, would have been hurled at those who would have dared destroy the original Mona Lisa, which supply and demand ideology ranks a million times higher than a mere exchangeable individual. Those who ideologise art deliberately use simplistic equivalents, amalgam techniques, to try to associate an attack on art with fascistic State repression, like comparing the act of an individual with what the Taliban did to the Buddhist statues. The accusation of ‘philistinism’ is often used against all those who for good material reasons have attacked art in the past.

We have no desire to offer prescriptions: we’ll leave that to the Leftists who, because they want to discourage any autonomous thought or activity, always know what’s best for us. And those who demand to know what they should do will be easy prey for the experts who try to provide positive solutions. However, it’s worth mentioning a few examples of past creative subversion that puts to shame all those who think that artistic forms can be genuinely rebellious:

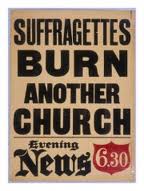

In 1914, on the eve of the first of many barbaric 20th century slaughters, Mary Richardson[14], a suffragette, went into the National Gallery and slashed Velazquez’s painting Rokeby Venus with a cleaver, breaching the sleep-inducing atmosphere with one swipe. Since then the museum has restored the painting and officially denies that the event ever happened: in the name of preserving the past, museums repress most of the past’s best moments. At the same time access to the archive material on the event is denied to those seeking it on the grounds that it is “classified material”, which the museum does not want published in order to avoid “giving people ideas”, ideas being the last thing museum culture ever wants people to have. More recently, an unknown ‘theatre producer’ [15] chopped off the head of Margaret Thatcher, unfortunately only in statue form – a symbolic act that undoubtedly pleased millions. Nevertheless, attacks of this nature don’t really amount to a critique of art, but rather a symbolic political attack on certain types of art.

In the 60s an artist in a small German town invited all the local dignitaries to the opening night of his exhibition. Whilst they peered at the pictures, the canvasses visibly decomposed in front of their eyes: the artist had covered them with a slow activating acid. The tannoy at the exhibition then blared out an announcement – “Would you please evacuate the building. The artist has just phoned in to say he’s left an incendiary device on the premises”. As the dignitaries left, the building caught fire, and the artist went on the run.

In 1968 Valerie Solanas, creator of the ‘SCUM’ manifesto, which had a pretty good critique of culture, even if it was falsely categorised as ‘male’ culture, shot and almost killed Andy Warhol, the vacuous vapid artist who once said he’d rather have been a machine than a human being.

In the late 60s a man who worked in a Blackpool rock factory was given his notice, but during the last week at work produced several miles of rock with the words “Fuck Off” written through the middle of it. Though unsaleable at the time, nowadays the culture of decomposition might very well turn such a product into a novelty item as long as it was produced officially.

In 1970, some radicals, at that time part-time lecturers in the history of art, set fire to a part of the Newcastle Arts College. Though never arrested and charged for it, one of them was blacklisted by the Economic League, and couldn’t even get a job in a factory after that.

In the mid-70s a few people went round an exhibition at the Royal College of Art next to the Albert Hall and spray-painted anti-art slogans all over the walls (“Art is dead but the student is necrophiliac”, “Art must be directly lived” etc.). When one of the guards came in and politely asked what they were up to, they said, “This is our art – it’s an experiment. We come in and paint all over the wall and another lot come in and paint over our slogans and then we repeat the action and so on…”. The guard, genuinely perplexed, walked off saying, “I’ll just have to check that…”, and the group ran off through the library.

In the mid-80s an installation at a Hackney art gallery was broken into at night and the art works, which included ones by the obsessively anti-situationist Stewart Home, were sprayed over with radical slogans such as “Dada did this before but better” and “Another Radical Wank”, and magazines by Home were pissed on. The installation was forced into an early closure.

Since these times, people have intermittently vandalised works of art – the Angel of the North was set fire to, and loads of other artworks have been attacked, but rarely have they been accompanied by a clear reason for the attack (the most recent attack – at the beginning of September 2005 – was the slashing of a Roy Lichtenstein painting by a German woman – not so much WHAMM! as RIPP!). Much of the time, it’s clear that these ‘vandals’ dislike the pretension of modern art or that they are disgusted with the way art is put up in green or open spaces or play areas on working class estates without the slightest respect for the environment or the people who inhabit them. Obviously we agree – it’s basic. But when it comes to attacking more classical art, the ruling world (and many of those who approve of attacks on the more modern rubbish) presents such attacks as the actions of madmen or bizarre eccentrics. For example, in July 2004 a guy who attacked “priceless” religious statues in Venice with a hammer was detained in a psychiatric hospital. Until such people find the words to express the anger they feel towards the object of their attacks, it is inevitable that the ruling world will define such actions for them – as ‘philistine’ or ‘crazy’.

PS

Section about THE ATTACK ON DUCHAMP’S URINAL

added 16/1/06:

Recently, on 6/1/06, Duchamp’s “Fountain”, an upside down urinal, voted most influential artwork of the 20th century by 500 of the most powerful people in the British art world in December 2004, was attacked by a performance artist, Pierre Pinoncelli.

The original ‘Fountain’ was refused permission to be exhibited in a 1917 exhibition apparently open to all, and has disappeared ever since. In 1917 Duchamp saw the ‘Fountain’ as a provocation – an attack on a very rigid traditional High Cultural definition of aesthetics, and, as such, was highly original, innovative, revolutionary even. But almost 50 years later – in 1964, having turned scandalous anti-art into an acceptable form of art itself, he made 8 replicas (i.e. bought some urinals and signed them, as in the original, “R.Mutt”). What is radical in one epoch is utterly conservative and banal in another. Such that nowadays even attacking modern art has become a form of art. In 1999, two Chinese artists, jumped on “My Bed”, Tracey Emin’s unmade bed with its empty bottles, dirty underwear and used condoms, on show at Tate Britain. The following year, the two artists urinated on Tate Modern’s version of “Fountain”. What is alienated here is not the fact of pissing around with the pretensions of art, but wanting to be merely well-known for it. They publicised their action by noting that Duchamp himself had said that artists defined art (of course, all specialists want to corner and define their niche in the market). Such innocuous “attacks” on art get plenty of publicity precisely because they are presented in the acceptable perspective of ‘art’. Whilst in the past, messing around with works of art without seeking fame was part of ‘subversive creativity’ in daily life, today the totality of a persons daily life has to be spectacularised, a means of self-valorisation as a ‘creative individual’, a career move.

It is for artists to define art, said Duchamp, and Pinoncelli’s act has already been hailed by many ‘rebel’ artists (artists who turn rebellion into money). Pinoncelli himself has always considered his acts as art, though with a tinge of left-wing politics – spraying André Malraux, de Gaulle’s Minister of Culture, with red paint in 1969, holding up a bank in Nice with a fake pistol and no ammunition to protest Nice’s decision to become Cape Town’s twin city while South Africa was still under apartheid, parading outside Nice’s courts, covered in large yellow stars, in what he called his homage to deported Jews, etc. Undoubtedly this guy is on the border of art and an opposition to it, but he can’t really shake off the need to perform. This shows how it’s not enough to merely attack works of art – you need to consciously develop a critique of the specialisation of creativity, its transformation into merchandise. There are some who think performance art transcends the normality of art-as-commodity, because it’s transcient, ephemeral, not tangible. On the one hand, this implies that only things become commodities, which is patently untrue. It also ignores the fact that much performance art inspires advertising.

Apparently Pinoncelli chipped off a bit of Duchamp’s piss-take urinal, which, although one of 8 replicas, is still valued at almost £3m. This exemplifies the almost absolute arbitrariness of exchange value – contrary to the claims of the more vulgar of the traditional Marxists, who claim that the price of a commodity is determined by the labour needed to produce it, and who hardly ever look at mere hype in relation to the art world, which seems to have similarities with fictitious capital. This is not to say that it’s not related to labour in some way – the value is seen in the supposed ‘original mental conception’ of a modern artwork, no longer in the traditional manual skills of the hands, i.e. in painting, sculpture etc: clever dick intellectual labour as opposed to manual dexterity, though of course previously there was a unity between concept and execution.

Maybe we have been a little ungenerous towards Pinoncelli – few people, at the age of 77, have done something as interesting as this. The guy got fined 214,000 euros ($302,446 or about £140,000) and was given a three-month suspended sentence. Brutal. Pinoncelli explained to the court he had attacked the work in the same absurdist spirit Duchamp had used to declare it art. “This was a wink at Dadaism,” Pinoncelli told the court. “I wanted to pay homage to the Dada spirit.” The trouble is using a spirit borrowed from the past, a spirit which has long been integrated into the art world, doesn’t connect to any understanding of the contradictions of this world. In 1991, another artist attacked Michelangelo’s statue “David” and damaged a foot. This guy was described as “unbalanced”, presumably because, like the previously mentioned guy who attacked “priceless” religious statues in Venice with a hammer – who was also psychologised into oblivion – his attack was against the generally revered traditional forms of art – though this was certainly not explicit. But explicit or not, such an attack on art has to be seen as a problem for the specialists in sanity, the uncreative specialists in getting people to adjust to an uncreative life in this utterly unbalanced world, the specialists in crushing people with sophisticated psychologistic vocabulary hiding crushing social relations.

ugly and work-oriented

aesthetics

as a specialised activity

will try to make it look

nice and playful…

Recommended reading: The Revolution Of Modern Art And The Modern Art Of Revolution by some of the excluded English section of the Situationist International and others.

Hits: 29/3/13 – 15/1/15: 1115

15/1/15 – 13/4/18: 4935

Leave a Reply