The following is a brief resume of workers’ struggles and their interaction with the State & capital starting a bit from the 1960s, but primarily about the period under Allende (September 1970 – September 1973).

It was written and translated by people in France.

The photos and quote at the end have been added by me, and the title is mine. (SF)

In the 1960s, the social and economic situation in Chile was disastrous. Revolt brewed in many sectors of society.

Workers’ struggles were growing in intensity. There were more and more strikes, two thirds of which were outright illegal. In the countryside, replacing the discreet and gradual reclaiming of land, a much more frontal, collective occupation movement was emerging, the tomas. Similarly, in poor neighborhoods (poblaciones), whereas before huge shantytowns had been built on the sly, now a more politicized, organized form predominated, the campamentos. Although the campamentos were often connected to one party or another, they genuinely tended to self-organize.

In the 1964 presidential elections, Christian Democrat Eduardo Frei bet on a specifically Chilean model of Keynesianism to pacify the tense social climate. He had the support of both American diplomatic interests and the right-wing parties, who withdrew their candidate in his favor, allowing him to win the elections easily. He set up grassroots organizations designed to contain the growing discontent on all fronts: greater union freedom, creation of cooperatives and welfare structures, institutionalization of already existing local associations such as the “neighborhood committees” or the “mothers’ centers”, land reform, and nationalization of mining resources (buyout of 51 percent of total assets). None of this, however, was at all successful in calming the surge of social struggles during his term. Ironically, the structures set up precisely for that purpose in fact had the opposite effect of anchoring the struggles in time and space and providing continuity for them to grow and intensify.

During the 1970 electoral campaign, the Christian Democratic Party (DC) and the National Party (PN) failed to unite. On one side, a fragmented right, and on the other, Salvador Allende who managed to unify the left in a “Popular Unity” coalition. The UP won the elections, though by only a hair’s breadth. Its program consisted of 40 measures: nationalization, land reform, freezing of electricity rates, universal health insurance, construction of 120,000 housing units, wage increases, job creation, legalization of divorce, free milk for children, amnesty for political prisoners, etc. These measures, which extended those of the previous administration, were necessitated by an economic situation calling for far-reaching reforms. The bourgeoisie perceived both these major concessions and the rising standard of living as necessary evils.

The nationalization of mining resources passed in Parliament, where the opposition held the majority of seats: the left and right wings of the Chilean bourgeoisie were in agreement that their interest lay in reincorporating these resources into the nation’s public sector, despite the risk of a falling-out with the despoiled American mining companies. The land reform, identical to that under Frei, aimed at boosting agriculture by eliminating the large but relatively unproductive latifundias and by promoting instead a plethora of small landowners in competition with one another. By the same token, the reform was expected to quell the veritable epidemic of illegal land occupations.

By late 1971, the State controlled virtually all mining resources and steel manufacturing, 90 percent of the financial and banking industry, 80 percent of export trade, and 55 percent of imports. The new government’s first half-year in power brought some improvements in daily life – price inflation slowed and unemployment dropped. In the April 1971 municipal elections, the UP won 50% of the vote.

Then the global monetary crisis hit, eroding these positive economic results. The price of copper, which accounted for 80 percent of exports, fell 30 percent while the value of imports, particularly food products, shot up 26 percent, bringing the progressive rise in living standards to a grinding halt. The country went into recession and real wages fell. By the end of 1971, Chile had depleted its foreign-exchange reserves. The United States terminated all aid to Chile, and Parliament refused flat to levy additional taxes. Government revenues went into free fall while public spending surged. No two ways about it: to ensure implementation of the promised measures, the government did what most other hard-hit countries were doing at the time – print more money, triggering still worse inflation.

At that stage, the bourgeoisie still considered the Keynesian wager – to increase production and stimulate the country’s economy by taking on the major monopolistic companies, etc. – worth a try. To ensure the endeavor’s success, workers’ participation had to be secured. The “battle for production” thus became a favorite UP propaganda slogan. As early as December 1970, the UP and the Central Unitaria de Trabajadores (C.U.T.) workers confederation reached an agreement defining an Area of Social Property (APS) within which nationalized industries would be grouped. In those industries, a form of co-management was instituted via the Production Committees. In the private sector, Vigilance Committees were put in charge of maintaining the highest possible level of production and preventing sabotage.

To break the deadlocks in Parliament, the government relied on a longstanding law providing for state intervention in the event of inordinate labor conflict or poor management. Workers often sought to sharpen conflicts, hoping to force application of the law. In addition to anticipating immediate gains, some workers had political reasons like helping the UP implement its program, while others were motivated strictly by social revenge, seeing state intervention as comparable to a slap in the boss’s face.

Yet C.U.T.-government collaboration, originally established to gain the workers’ trust, began having the opposite effect. Trade-union officials and civil servants, intent on mediating between the UP’s industrial planning requirements and the workers, were rightly suspected of political opportunism. Brought in by the parties, these bureaucrats soon proved to be just a new set of low-level bosses. Workers sometimes agitated to get the bureaucrats fired and replaced by people from their ranks, more legitimate in their eyes.

Certain qualitative changes were taking place in the most actively militant factories, where the Vigilance Committees went beyond their original function. Workers, dissatisfied with doing the same job as before only faster, reorganized production to focus on meeting basic needs. Some pointed out that: 1) without control over distribution, their efforts to satisfy needs more cheaply just put money in the middlemen’s pockets; 2) in the private sector, raising output enriched their boss; 3) in nationalized companies, most of the profits went towards indemnifying the infamous former bosses! A major protest movement developed over these issues, but in vain. The government, unwilling to challenge the defense of Private Property, paid most of the “victims of expropriation” compensation on the nail.

Nothing had changed fundamentally for most people, and the tension hadn’t eased between the need for productivity and stubborn resistance to work. Allende was haunted by continuing class struggle under a left-wing government. As he saw it, the risk of “excessive” worker demands was “the regime’s Achilles’ heel.” His objective was to take over key companies, energy resources, exports, and sectors vital to the economy in order to prevent blocking by the bosses and imperialists. He lacked the resources to cover payrolls as well as investments in more than 10 percent of the factories and planned to leave the remaining 90 percent in private hands.

Nonetheless, the movement to socialize companies met with overwhelming success. Private-sector workers, who looked on enviously as APS companies obtained improved conditions, began requisitioning, forcibly and much more widely than initially foreseen! The government didn’t dare oppose this movement and legalized whatever had been seized illegally, so as to maintain at least a semblance of legal compliance. By late 1972, 250 companies had been socialized, far more than the 91 Allende had planned a year earlier. Eighty other companies formed cooperatives.

The UP couldn’t afford to put everyone in those companies on the payroll, especially since it was barred by Parliament from levying new taxes. It was left with one option – by freezing prices, it could increase wages indirectly and win over the poorest parts of the population. At the same time, however, this squeezed proceeds from sales, and the nationalized companies’ income fell far short of the cash flow they required. Another consequence was that merchants, seeing their profit margins shrink, decided to create artificial shortages and sell their goods on the black market. The resulting scarcity was hard on everyone except the rich, who could afford to buy whatever they needed on the black market, at ten times the official price. The government ran public distribution agencies, but distribution was for the most part controlled by private middlemen, and the government was powerless to deal with the massive fraud. Many considered this a lack of political courage and demanded that the government wield a mano dura or iron fist against the profiteers.

In July 1971, the UP’s left wing established the JAPs (Juntas de Abastecimiento y Precios) or supply and price control committees. Formed from existing neighborhood organizations, they were initially intended to control prices and ensure that stores stayed well stocked. The JAPs were very successful and, a year later, totaled 675 in Santiago alone and 1000 nationwide. Depending on where they were set up, their social content varied greatly: in some places, they remained bureaucratic bodies; in others, they were a cover for fraud and individual gain; elsewhere, they belonged to the network of rank-and-file organizations and gained strength from the influx of local volunteers. In practice, they were not entrusted with any enforcement powers. A JAP which introduced ration cards in March 1972 caused an outcry on the right. The latter forced the JAP to give up the system, even though the ration cards had done away with the queues and deprivation characteristic of the previous “first come, first served” system.

In June 1972, the Cerillos-Maipu Cordon Industrial (industrial belt) was formed on the outskirts of Santiago. It was no accident that such an approach first developed in that neighborhood, in that Cerillos was Santiago’s leading industrial suburb, comprising not only 250 companies which employed a total of 46,000 workers but also some 30 campamentos. Maipu was the nearest farming region, producing 70 percent of Santiago’s vegetables. The area was crisscrossed by a network of major highways, an access to the port, key railway lines, etc. Blocking any one of these would have immediate consequences for the capital city. It had strong traditions of struggle and, more broadly, of proletarian associations which maintained relatively close-knit social ties through neighborhood festivals and sports events.

At the time, there were major struggles in the area. Some companies’ workers were unsuccessful in imposing their incorporation into the APS. Workers there, surmounting their political differences, took part in the meeting organized to help them out, joined by workers from nearby companies and pobladores (poblacion dwellers). They built and maintained barricades for several days, until their demands were met. Galvanized by this victory, the Cordon called for a demonstration in support of farmers arrested during a land occupation. From that time on, the industrial belt could count on a standing core of some 500 committed, militant people always ready for action. At peak periods, the Cordon was capable of calling out as many as 5,000 people. The movement, as yet only embryonic, would come to fruition during Red October.

Throughout the country, trade unionists in companies that had been incorporated into the APS recognized the necessity of linking them together at rank-and-file level, in contrast to the CUT which functioned vertically and had no kind of local union structure. The labor code prohibited the creation of unions in companies employing fewer than 25 workers or in which none had won an election by at least 55 percent of the vote. This meant that huge numbers of workers could not legally form a union, in contrast to the largest and most important companies, where the UP focused its attention. The need to develop new rank-and-file structures for workers’ struggles, especially in small companies, is no doubt the reason for the emergence of so many other Cordons.

Gaudichaud estimates at “30,000 the number of workers and militants who identified with the collective action of the Industrial Cordons in greater Santiago and responded to their calls. Nationwide, and in every province, there must have been double that number (…). Nevertheless, most of the time, only a few dozen people participated in the Cordons’ general assemblies.” This sizeable gap not only reflects the overall level of social conflict at the time but shows how these bodies shifted between two extremes – predominately political in certain periods and, in others, hubs of revolutionary activity.

Right to the end, the Cordons remained contradictory. They were at once rife with political squabbling, reproducing locally the deadlocks of democratic debate and para-unionism and convergence zones of simmering social discontent, affording a qualitative leap in the movement. At first, party officials were taken by surprise. Allende, the CP, and the CUT opposed this surge of activity, whereas others, in particular the Socialist Party’s left wing, seized the political opportunity offered by these bodies and directed their militants to get involved. This grassroots structure, independent of the CUT, enhanced the Socialist Party’s influence among the rank-and-file, in a worker stronghold. The Communal Commandos, formed later on with the MIR’s encouragement, were intended to have a broader reach than the Cordons because they included pobladores and peasants. Nevertheless, the clear-cut distinction between Cordons and Commandos as portrayed by the parties in their neat organization charts did not reflect the reality of many Cordons, particularly in the provinces, which also encompassed nearby pobladores and campesinos.

The development of these various structures was a dynamic process reflecting a need for organic centralization of differing realities in struggle: city-country, peasants-workers, production/distribution, etc. This process played out in every one of the country’s regions, although to varying degrees of structuring and strength. Depending on the moment, it was embodied in the Cordons, the Communal Commandos, the JAPs or the pobladores organizations. The concept of a dynamic process is worth stressing in that names attached often lead to fetishization, to an ossified understanding.

Despite the political failings of their party leadership, many militants in the MIR, the Socialist Party or others shouldered a decisive approach. Numerous militants, determined and hostile to the UP’s reformism, joined together in the Cordons, the Communal Commandos or the MIR-initiated “mass fronts.” In the poblaciones, some militants modestly supported existing practices, giving them a framework and continuity, and fostering the emergence of specific “fronts”: “Health,” “Popular Justice,” “Women,” etc. Despite their tendency to categorize, these fronts gave everyone practical opportunities to get involved on very concrete bases of immediate action.

All of this is difficult to assess because accounts by militants emphasize these structures’ charters and organization charts and inflate figures while not actually describing their social reality. Without underestimating their failings, these committees served as points of convergence to mobilize energy. To a certain extent they helped counteract the corporatist tendencies and efficiently organize coordination of all the many different social forces. The committees could well have remained empty shells, but they appeared to fit the needs of the rotos (Chilean rabble) and their struggles, especially at the peak of the class war that unfolded in October 1972 and in June-July 1973.

During the winter of 1972 (the northern hemisphere’s summer), UP leadership was outflanked by its rank-and-file. The governing parties organized a crisis meeting in June 1972 known as the Lo Curro conclave, where they decided to reassure the bourgeoisie by taking a break to “consolidate the alliance with the middle class” and the CDP. The decision was made to halt extension of the state-owned sector, to remove price controls in order to increase cash flow in the APS companies, and to put an end to “illegal” occupations, if need be through unbridled repression.

The opposition, initially paralyzed by the UP government’s electoral and economic successes, began regaining strength right from the first failures. It united under the banner of the Democratic Confederation (CODE). On October 11, the truck owners’ guild called an indefinite strike, with the support of Patria y Libertad (paramilitary) squads. Significantly, virtually all transportation of goods is by truck in Chile. The government declared a state of emergency, detained the movement’s ringleaders and requisitioned the trucks. Out of solidarity, the middle-class organizations all joined the movement. In a joint statement – the pliego de Chile – they repeated their demands, which included restoration of private property, company security, and disbandment of the JAPs.

The situation of the poorest, ignored in UP policies and hard hit by shortages and devalued real wages, had become untenable. With the truck owners’ strikes, their very survival was threatened. The rotos entered the battle. Throughout the country, locked-out factories were taken over, production restarted and output seized, trucks were requisitioned, expropriated goods were handed out. The county’s 2,000 JAPs used all their organizational power to tip the scales and forcibly opened striking warehouses, accompanied in some cases by hundreds of determined pobladores or far-left militants accustomed to confrontation. They took control over distribution in poor neighborhoods, and the premises of merchants suspected of speculation were sequestered.

Some of the JAPs established direct relations with factory committees, organized goods sale or barter between factories, and set up a coordinated production plan. Any JAPs suspected of mercenary dealings or political opportunism were bypassed, and “people’s stores” managed directly by pobladores were created. Supermarkets were taken over, and thousands of families registered as members. The food, produced at sympathetic factories, by neighboring peasants’ movements, or even from State Distribution Agencies, whose officials had more confidence in the committees than in the government networks, was then sold directly, often at cost price [note: at the cost of production, without any additional profit]. Behind all of this were the contacts made among the committees of pobladores or workplace representatives, the JAPs, the neighborhood committees, the mothers’ centers, the peasant movements, etc. Involved in the joint action were militants and sympathizers belonging to various parties, including Christian Democrats.

Admittedly, the illusion of rule of law persisted. Even though the issue of legality had seemingly been swept aside by the agitation escaping UP control, most of the protagonists still had a legalistic outlook. In other words, the break was real but not explicitly manifested. The majority of insurgents continued to think they were defending “their” government, with the latter’s support and recognition.

The very existence of such tendencies, though in the minority, represented a severe threat to the Commodity World. In a period of acute social crisis, any clever initiative could spread like wildfire. Whenever some peripheral practical action proved effective, the rotos were eager to pitch in, whatever their avowed political sympathies. True, at that specific moment, the challenge to the foundations of Exchange, Value and Labor was no more than superficial, but it was a turning point: whereas the rotos continued to produce and distribute commodities to fulfill their immediate needs and freeze prices, the ultimate outcome could only be a much more far-reaching subversion of the Economy. Whereas the rotos’ conception at the time was limited to a capitalist planned-economy model, including “reasonable” prices and “decent” wages, they were heading towards a far broader horizon. It was a serious moment for the momios (the right wing).

To put out the fires of the Chilean October, Allende opted for a conciliatory approach towards the reactionaries and their demands: no more repression, no sanctions against the strikers, a promise never to nationalize the transportation sector, return of all illegally occupied companies, passage of an arms control act authorizing the army to carry out searches anywhere and recover all weapons held illegally. A state of emergency was declared, and three generals as well as several CUT leaders joined the government. From January 1973 on, each of these cards would be played as trumps in the battle against the rotos:

The military card was used to gradually restore control over distribution. General Bachelet tackled the people’s stores, suspended their supplies, got rid of any public service employees who had encouraged direct distribution, etc. The JAPs’ functions were reduced to the bare minimum.

The trade-union card was used to do away with land seizures and illegal factory occupations. The “Millas program” provided for socialized companies to be restored to their owners, indemnification of major shareholders, reinstatement of many managers who had been kicked out by the workers, ousting of ministers guilty of having given in to pressure from the streets and their replacement by members of the military capable of “reassuring” the bourgeoisie.

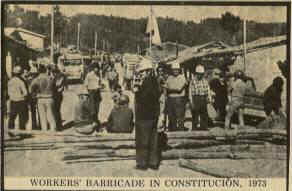

In reaction, the Cerillos-Maipu Cordon occupied the neighborhood and erected barricades. The whole of Santiago’s Cordons met to draw up an “immediate action plan” demanding incorporation into the APS of all manufacturers of vital commodities, major distribution companies and landholdings exceeding 40 hectares (99 acres), withdrawal of the Millas plan, the creation of workers’ vigilance committees to prevent the return of any companies, empowerment of the JAPs and Communal Commandos to carry out sanctions, the introduction of direct sale to pobladores, stable, guaranteed employment in the construction sector, endowed with an adequate budget to avoid unemployment, etc.

Tension heightened as the March 1973 legislative elections approached. The opposition counted on the strong likelihood that the UP would get less than a third of the votes, allowing it to oust Allende legally, but it won only 55 percent. The opportunity was missed, and there wouldn’t be another one for a long time. From then on, it was obvious that the bourgeoisie’s right wing had no choice but to find another way of achieving its ends.

That other way was a military coup d’état. Historically, Chile’s armed forces enjoyed a loyalist image. It can be reasonably assumed that this loyalty was less a sacred principle than a question of self-interest. The UP would be given a chance to subdue the rotos’ thirst for social revenge, but if it failed, the coup d’état option would always be available. And in fact, the opposition and the government alike relied increasingly on the army to restore order. How could the military be expected to keep a level head when the whole situation seemed to be rolling out a red carpet for it?

On April 17, 1973, the miners at El Teniente went on strike for higher wages. Yet the UP refused to give in to their demands, fearing similar demands would be raised everywhere. It described the demands as disproportionate and the mark of a “workers’ aristocracy.” Since his election, Allende had already managed to break other miners’ strikes by appealing to “national solidarity.” This time, however, the majority of miners refused to tighten their belts. Their position in the Chilean economy gave them a weighty edge in the balance of power. The strike lasted 74 days and had disastrous consequences for the national economy.

The opposition exploited the discontent and rushed to the aid of those “heroes of national production, victims of the UP,” while wealthy people took up collections and doctors, teachers and students went out on solidarity strikes. On June 14, the miners marched on Santiago. In reaction, the CUT and the Cordons called for a demonstration the following day, which brought hundreds of thousands into the streets. Violent clashes, which were later exploited by both sides, left one dead and sixty wounded.

The Cordons, however, were ready for more and went on the offensive. Losing no time, the Cerillos Cordon, with the collaboration of the Maipu peasants’ council, seized 5,000 hectares of land (12,350 acres) to get their hands on “Santiago’s vegetable garden.” A disused slaughterhouse was requisitioned and used as a people’s store for a few days. Some of the land seized belonged to members of the CDP, so the UP pressured the Cordon leadership until, seething with rage, they handed it back. Relations between the conciliatory and left wings of the UP were increasingly acrimonious. The Cordons and the Communal Commandos became more radical, and even the worst political schemers among their officers grew tired of the national leadership’s calls for moderation. The very vague notion of “popular power,” a slogan in demonstrations, took on content that was increasingly antagonistic to the UP.

The “Tancazo” took place on the morning of June 29. Tanks belonging to the second armored battalion encircled the La Moneda presidential palace and presented an ultimatum demanding the government’s resignation. The response was immediate and well coordinated: factories were occupied, barricades were built, and self-defense brigades, formed in a rush and haphazardly armed, dashed to downtown Santiago to attack the seditious forces. However, it was General Prats who rallied the loyal troops and obtained the mutineers’ surrender. The UP brushed aside its civilian defenders and urged them to let the army do its job. At the time, both Allende and the CUT were in favor of factory occupations, which they saw as merely a short-lived, symbolic protest. Yet to their great displeasure, the factories were held steadfastly for several days. Allende and the CUT pleaded with the occupiers to vacate them. The courts declared the occupations illegal and ordered the occupiers’ eviction, but to no avail. In fact, a good number of owners only got their property back after Pinochet’s coup d’état.

The Tancazo served as an electroshock, kick-starting the factory seizures and the people’s stores which were losing momentum. Some zones almost completely escaped government control. Workers belonging to the CDP sympathized with or participated in the Cordons and illegal requisitions. CP rank-and-file militants, who’d stuck loyally to the party line since the beginning, began to break ranks.

All this agitation reached a peak at the end of July, in what was known as the “Cordonazo.” On July 18, 5,000 people blocked the streets of Cerillos-Maipu, chanting “No conciliation!” and demanding an end to factory evictions as well as full expropriation of the food industry and distribution agencies. They were joined by workers from the Vicuña Mackenna Cordon. The police attacked the barricades, wounding many people, killing one worker and arresting others. This marked the start of a vast wave of repression that would wreak havoc during the following weeks. Their comrades advocated the creation of a people’s militia but the leadership of the Cordons decided against calling for the movement to continue. Tragically, this was to be the Cordons’ last major offensive before Pinochet’s coup d’état.

Substantial numbers of rotos were left more and more confused by the governing parties’ contradictory politics. Militants were increasingly fed up with the leadership but suggested no course of action capable of materializing that break. Dismal inscriptions appeared on Santiago’s walls—“Jakarta!” in reference to the wholesale massacre of Indonesian communists in 1965. In late July, the opposition underlined Allende’s inability to command obedience when he demanded the return of factories occupied since the Tancazo. The truck owners went back on strike, and the pace of attacks by Patria y Libertad reached a climax. The way was ever more clearly paved for a coup d’état.

In preparation, the army launched full-scale domestic warfare exercises, for which the gun control act proved useful. It attacked the most combative factories, occupied CUT offices, sent a number of Cordon leaders to prison, dispersed crowds of pobladores trying to force stores to sell goods, stormed the headquarters of left-wing parties, burst in on trade unions, factories, farms, schools and universities. It searched methodically to uncover every last arms caches and conducted heavy-handed interrogations.

On August 7, a network of loyalist sailors was eliminated, hundreds of men were arrested and tortured by their officers. On August 9, Allende formed the “National Security Cabinet” in an attempt to reassure the opposition, but that no longer sufficed. The bourgeoisie’s right wing wanted his head, the Chamber of Deputies declared the government illegal and enjoined the army to choose sides. On August 24, General Prats, the last loyalist bastion inside the army, was forced to resign. Allende appointed General Augusto Pinochet commander in chief of the army.

On September 4, 700,000 people marched in support of Allende, who promised a referendum on September 11 to give the opposition an opportunity to express its differences democratically. But he was not to have time for that. On September 11, 1973, the army assembled in front of La Moneda while it was bombed by the air force. At noon, there were still 20 resisters, but by 2 p.m. the end had come. Allende committed suicide.

The army could have refused to follow the mutineers despite the meticulous cleanup in preparation. In some places, arms were expropriated from police barracks or stations, but too few. Hundreds of thousands of potential combatants in Santiago, unarmed, faced 50,000 soldiers terrorized by the seditious generals’ tales of an impending dictatorial offensive by heavily armed Industrial Cordons, which justified the coup d’état. In short, the putsch had been prepared like a Blitzkrieg to prevent any possible reaction from the poblaciones.

The generals’ description of a “putsch by the reds” was strongly influenced by their militaristic conceptions, but they nonetheless had a fairly sound grasp of the situation: a break with democratic pacification, a kiss-off to the whole clique of smooth-talkers in government or parliament, and an offensive defying bourgeois democratic law, i.e. dictatorial—such was, in actuality, the one thing the army had to fear. The far-left parties did talk about such a solution, fueling the bourgeoisie’s fear, but they never actually acted on it by organizing preparations to that effect. Tragically, their words were enough to earn the rotos’ relative trust, whereas their acts systematically aligned with the practice of the UP, viewed as a neutral entity, exterior to the ongoing class war. The rotos, repressed, discouraged, physically and ideologically disarmed by the UP, were finally finished off by the putschists.

“Allende’s biggest mistake was not giving us weapons. A lot of people even women, would have fought”

– Chilean housewife, quoted in New York Times, September 24, 1973.

Above: Allende, September 11 1973

Below: General Pinochet

See also“Strange Defeat”, written in October 1973

Leave a Reply