” It is the audience who makes the art…. What an audience! Whoever wants to look the twentieth century in the face cannot do better than stand behind the screen in a big cinema…

The audience of the music hall are bright, consciously convivial, aware of their neighbours, and taking their enjoyment in company. The music-hall spreads an invisible festive board. But in the cinema it is a ghostly bed which awaits you. There the audience is as disunited and dim as the guests of an opium den. All those parted lips and staring eyes express no convivial enjoyment, they are lulled out of life, journeying along the moonlit paths of dreamland.”

[Abbreviated from Jack Common’s “Behind the Screen”, (The Sweeper Up), in The Adelphi vol. VIII, December 1933. As reprinted in Revolt Against an ‘Age of Plenty’; see the writings of Jack Common – and here also]

What’s there to say about movies that hasn’t been said before, particularly by Jack Common and especially after him – by the Situationists?

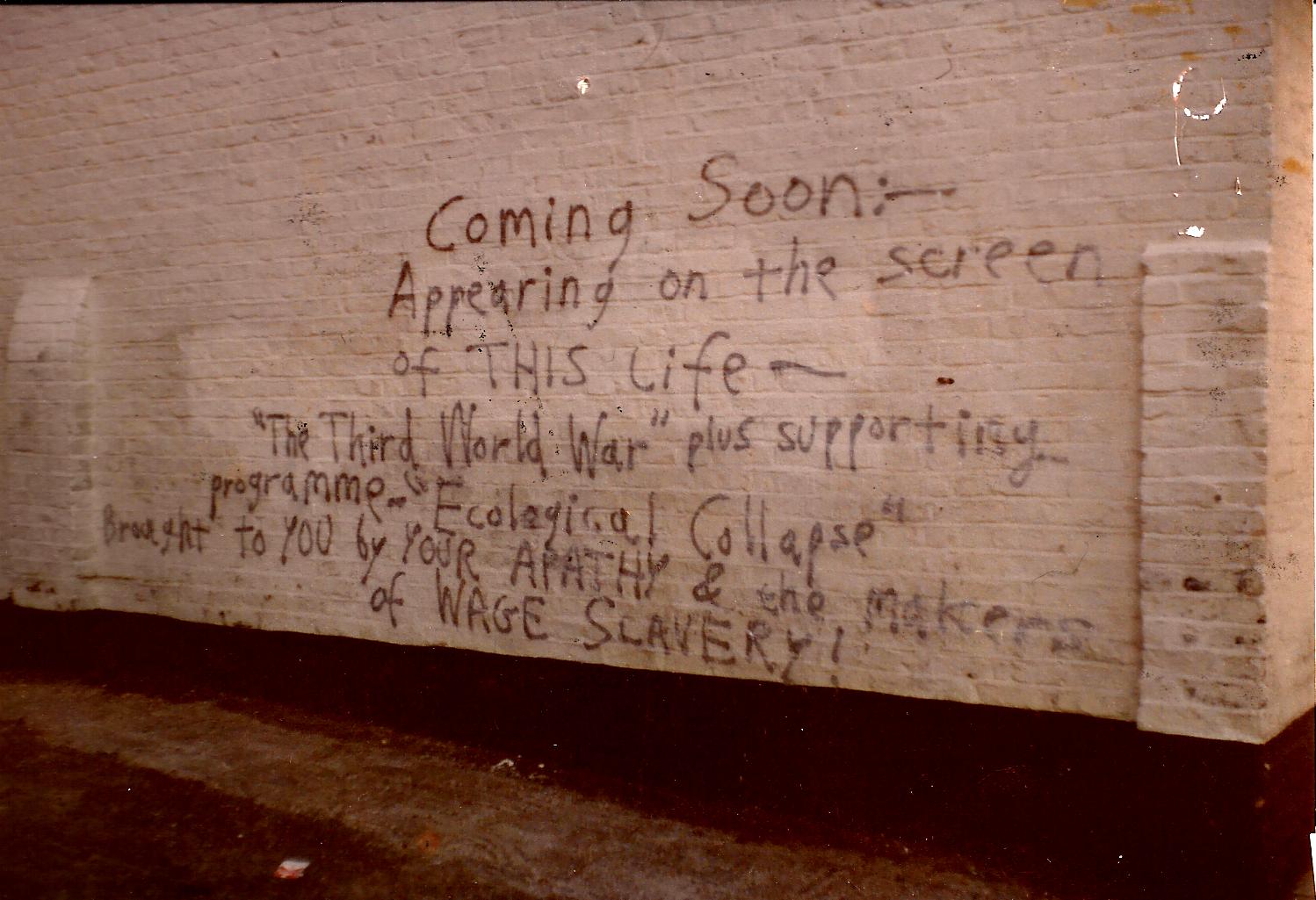

Organised within a strict hierarchical division of labour, the endless different stories, the endless different acting, the endless different background music, the organisation of sound, the photography, dialogue, facial expressions, technological graphics, sets and costumes, etc. all hide an essential unity – the commodity form, the repressive form that makes all these vastly different spectacular forms of ‘expression’ attractive, a variety that’s well worth paying for because it seems to compensate and distract from the repressed uniformity of a daily life that has not been worth paying for.

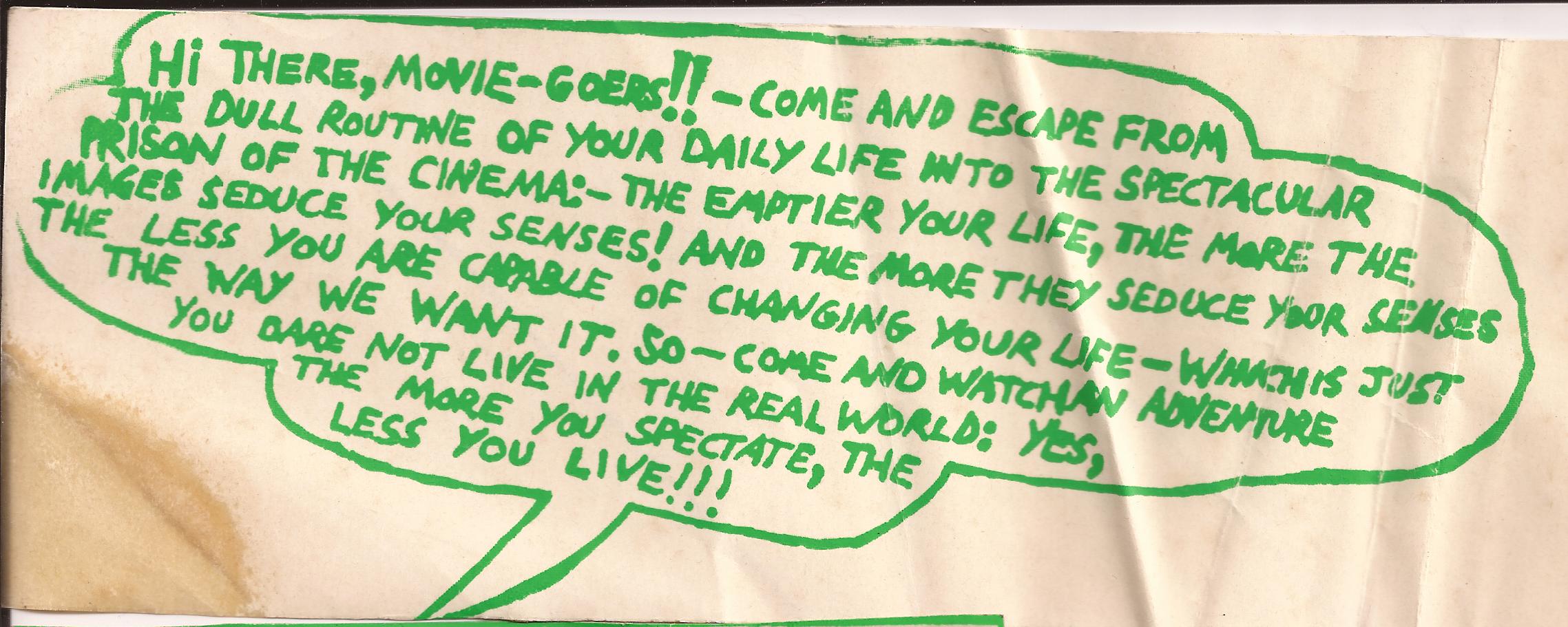

Most people look at movies just as consumers – or fantasy would-be producers; the actual social relations that go into the production line of these cultural commodities – the miseries and boredom of what goes on – is very obviously not the reason they see a flic (French word for cop!). Most people don’t want to know all that – they go to the pictures mainly to ‘escape’. Unlike in daily life, you get excited, surprised, delighted, scared, sad, intrigued, aroused or whatever by something which has been thoroughly rehearsed and cut up and re-organised to produce this effect, something inevitably devoid of all spontaneity and risk. But complete so that one can have a fixed opinion of it. Above all , safe – and a safe topic of conversation.

This is not to say that movies don’t have some kind of ‘quality’: as against those who only criticise the social relations of the cinema, it’s also important to analyse their immediate content. In the vastly differing unique interaction of various subjectivities, reduced to the specialism necessary to turn this repressed submissive subjectivity into a means of making money, films represent real desires and real contradictions repressed by the current stupid system. This is regardless of what you think of the final product. For us, questions of taste are secondary – a judgement of a film purely in its own terms. In a sense, even the crappiest movie has some quality, because of the real life, its contradictions and desires, that a film expresses, despite the crap way it expresses them.

The film Titanic, for example, represents a real disgust for the class system that always kills the poor first. And one can argue how well it does this. But let’s look below this superficial question. Despite the fact the film reduces its criticism of class relations to something that happened in the past, with its aesthetically pleasing period costumes, and an object of interest simply because of the assumptions of the epoch, the ‘irony’ is that during the making of this film, 3 Mexican extras were drowned. We don’t know if they had already swum across the Rio Grande to get to be extras but what’s important is that this, of course, isn’t really an ‘irony’: even whilst Leo di Capprio was earning £12m. or whatever, those at the sharp end were paying, as usual. Hollywood was built that way.

Other movies (e.g. that Tim Robbins one whose title I’m not sure of – The Player, I think)) portray the ‘real’ horror of Hollywood. Hollywood knows that being open to criticism makes it appear ‘free’. It has learnt, like the rest of society, to absorb and co-opt criticism all the better to make a profit, pull in the punters. The pretension of the cinema to ‘social criticism’ is not meant to be taken seriously of course, but just followed at a short distance. A guy playing a down and out bum whom we know is getting paid $20million is a crude example of this. Shortly after Kevin Costner made the film “Dancing With Wolves”, a sympathetic portrayal of how vicious the whites were to the Native American Indians, he bought a piece of land cheaply off the Indians and transformed it into an exclusive golf course. To accuse him or the makers of Titanic of hypocrisy is not the point: spectacular culture is inevitably hypocritical. Within the logic of economics and cultural commodities, criticism is no criticism at all because, implicitly, the solution that comes to mind is “make another – better – movie/TV programme”; the need for art, for spectacular commodity production and consumption, begets itself – begets the need for art, for spectacular commodity production and consumption, a self-referential vicious circle. This safe representation of the poor usually as purely victims, or even occasionally as winners (e.g. in Total Recall) – accepted in its own terms – inevitably represses the possibility of not just being a victim or of maybe becoming a winner. It’s not usually for this reason that movies are often seen as escapism – but it should be.

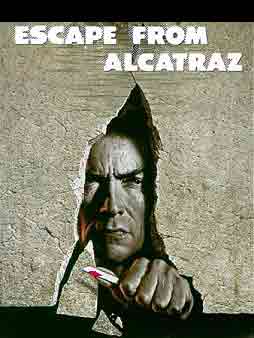

For example in the corny or not so corny variations of the cop car chase, from the Keystone Kops onwards to its science fiction versions, we can see a real aspect of reality: we often have fantasies of a confrontation with cops or the State, or of being threatened by someone powerful – only occasionally, usually in moments when we in some way or another confront this world, do these fantasies become reality. In some ways, the chase is somehow a representation of this feeling, and of this real experience (as well as a fantasy that contradicts the misery of driving along motorways or through traffic jams). But like all movies, this representation of critique and desire represses confronting people’s contradictions or of expressing their desires (well, no-one’s going to wreck their car and risk their lives in some crazy rebellion against traffic regulations – except in the South of France). So someone watching a chase scene is far more likely to be inspired to drive a fast car or to make a different movie version of such a scene than actually put themselves in a situation where they really might have to get away quick. This is true for the desires and contradictions of both those who produce movies (particularly those at the bottom end of the production process) and those who consume them. Hence the representation of getting away from the cops or some super powerful crooks really is an ‘escape’, an escape from trying to do something against the real super crooks/cops that dominate our lives. But then that’s true of all movies – the idea that ‘serious’ movies are not also an escape from imaginative activity against this world is never mentioned by the snotty sophisticates who despise ‘normal’ movies as mere ‘escapism’.

Basically most of us watch a movie to ‘unwind’, to empty our heads – sometimes on our own on a DVD or video, sometimes with a couple of others, as an occasion at the cinema – we hope to relax ourselves. ‘Relaxion’ is seen as something like being given a story at bedtime, to lull ourselves to sleep. Being treated like children we like falling into fantasies, sitting back and imagining being him/her on the screen, the hero or heroine in a story…Story-telling has always been a way of sending us to sleep, lulled safely in the belief in happy endings (though of course nowadays there are endless movies without happy endings because it more and more feels like nothing can have a happy ending). And then we try to predict a story line that’s totally out of our control (which also feels like the story of our passivity towards the world hurtling towards disaster). Making predictions of what’s going to happen next is about as far as our passivity gets stretched – we keep our distance by treating the whole scenario as a guessing game, pitting your wits against the scriptwriter, and yet there’s always the thrill of surprise you hadn’t reckoned with. In fact, the aim of most movies is to pack in as many surprises per minute as possible, because in daily life there are so few, and most of them are nasty. And because we like to pretend we are in control over our lives by not being surprised, we try to predict this fictional future so as not to be surprised.

Unlike in purely verbal or written storytelling, nothing is left to the imagination: you just have to suck it in without transforming it even in your head – in your imagination of how the characters look, their voices and tone, what the environment looks like, etc. etc. that you get when there’s nothing visual. So the guessing game – what’s going to happen next? – becomes the narrow and last terrain of the imagination…

* * * * * * * *

It’s within this general framework that we look at films on this site, not from the banal leftist/ultra-leftist differentiation of films with an apparently radical content and those with a reactionary content and those in between, or whether they provide positive role models for women, gays, blacks etc. Whilst the immediate content of a story and dialogue, etc. might be more or less interesting, this content is certainly not something that should be purely assessed in an uncritically positive manner, within the corny everyday dialogue that gets everyone into playing the amateur critic.

* * * * * * * *

The use of technology – a cassette, video or CD, for example, – can be against this world but one has to be very wary of not fetishising forms (e.g. the internet) of communication, and using specialisation in a unilateral manner…Writing, for example, is just one form of contact: its not just a question of criticising content but also one of festishising one particular form.

* * * * * * * *

Most of the above, though, is essentially ahistorical: much of it could have been written any time over the last 40 years. But the immediate content of a film is almost invariably dependent on social changes, on changing attitudes in different epochs, as are the precise social relations that go into producing a film: there’s a world of difference between Un Chien Andalou, Guy Debord’s early movies and anything produced nowadays, for example. All this is very general and meandering as usual – and the two texts on the site so far don’t concretise these ideas very much further, but so far we haven’t had time to get down to this. Give us a reason why it might be useful, and maybe we’ll continue this train of thought…For example, we could look at how story-telling has changed through epochs – from Aesop to Dickens to Eastenders to Reality TV; how the social occasion of storytelling has changed from sitting round in a circle to Dickens read out in public places to Sherlock Holmes serialised in a magazine to the Theatre to Music Hall to radio drama to movies to TV to increasingly just watching a movie on your own. And we could examine more about the contents of movies representation of real proletarian desires, whilst looking at some ideas for a practical attack on the more tactically useful movies worth subverting…

But maybe you should.

“The cinematic spectacle has its rules, its reliable methods for producing satisfactory products. But the reality that must be taken as a point of departure is dissatisfaction. The function of the cinema, whether dramatic or documentary, is to present a false and isolated coherence as a substitute for a communication and activity that are absent….Regardless of its subject matter, the cinema presents heroes and exemplary conduct modeled on the same old pattern as the rulers….The events that occur in our individual existence as it is now organized, the events that really concern us and require our participation, generally merit nothing more than our indifference as distant and bored spectators. In contrast, the situations presented in artistic works are often attractive, situations that would merit our active participation. This is a paradox to reverse, to put back on its feet.”

– Guy Debord, Critique of Separation

P.S. :

The following snippets about films and cinema are from other texts on this site:

From “Notes on the secondary school movement in France, spring 2005”:

“The recent popular French film Les Choristes depicts a pion from an earlier period – early 50s. The film takes place in a vicious boarding school for ‘difficult’ kids, often in trouble, orphaned or just a burden to their parents, where the ‘pion’ is a middle-aged classic sympathetic authority role. The clichéd, oft repeated, nice authority role in a nasty dictatorial sadistic environment, enforcing a milder form of discipline whilst reluctantly going along with many of the heavier aspects but also ‘revolting’ against it, is the main character. This revolt takes the form of secretly (against the tyrannical headmaster’s wishes) conducting and helping the boys sing as a choir, which of course gives most of these previously ignored and often brutally suppressed kids a way of ‘expressing themselves’, at least two of whom later become world famous musicians themselves.

And they ‘express themselves’ so beautifully too: the record of the film is a top seller. The (unpaid) teenage choir is followed by fans singing the classical-style tunes. The real choirmaster who teaches this choir to perform in the film and now in concert halls is not at all sympathetic – but a typical rude humiliating bossy choirmaster openly displaying his nasty manner to the documentary cameras. But the kids seem to like producing a beautiful product despite the heavy social relations, which aren’t even based on wage slavery – just slavery straight. Perhaps part of this is their parents’ pressure, but undoubtedly the biggest seduction for enduring this is the fact of becoming celebrities, the compensation for miserable social relations. The tautological nature of this society is thus well affirmed by this well-made film: culture, the production of ‘beauty’, appears as the way out, though the hierarchical relations involved in producing culture are just as ugly and bad as the misery for which culture appears to be the way out.

This film comes 80 years after another, far more innovative and – for its time – subversive, film which also portrays a sympathetic pion – Zero de Conduite (“Zero for Conduct”) by the French anarchist Jean Vigo, a silent movie from the 20s which influenced the recuperative movie “If” in the late 60s; Vigo is now accepted within the mainstream of French culture, with media libraries named after him – but that’s down to the enormously recuperative power of French capitalism, in particular its culture (mind you, what, worldwide, isn’t co-opted into the system in some way or another over half a century, and often a lot less, afterwards?) “

From “You make plans – we make history”:

A sector of Hollywood continually sells catastrophe back to us, with its endless digitalised graphic presentations of Earth-crashing asteroids, gigantic floods, colossal fires and deadly epidemics, etc…Initially, the terrorist attack on the twin towers caused a terrible disaster…for Hollywood: “real life” had surpassed the endless catastrophe movies, previously seen as unrealistic, so this sector was temporariliy seen as no longer profitable – for that moment at least. Spielberg was one of the first to rectify this in his crass War of the Worlds movie, which very obviously evoked 9/11, complete with happy ending – the defeat of the alien baddies. Another recent Hollywood movie – The Day After Tomorrow – depicts ecological catastrophe but in such a ridiculously over-dramatised way (events which would take a few years to develop happen over a few days) that it somehow trivialises the ecological horror creeping up on us, since it comes over as so unbelievable. This is not an appeal for ‘realistic’ catastrophe movies – apart from the fact that movies almost invariably reinforce passivity, the ideology of catastrophe tends to breed a petrified fatalism. (very slightly altered from original text)

From “Aspects of a history of the British miners”:

“The pits were closed not with a bang but a whimper: each individual pit was subject to a review procedure, there was a media blackout and each pit was closed one by one in isolation. The film Brassed Off illustrates this defeat: oh how the culture industry love tragedies – a real victory of proletarians in struggle would be beyond them, partly because it would have to take on the culture industry. And of course, the content of the film reveals the circular tautological nature of culture: in the form of a musically exquisite brass band, culture is seen as the consolation for, the one redeeming result of, tragic defeat (with a very different – partly feminist, partly gay liberationist – content, there’s a similar underlying thread in the film Billy Elliott, most of which takes place during the miners strike; and also one could mention The Full Monty, with its backdrop of the decimation of the steel industry, in this vein – the culture in this instance involving humiliating yourself as a male stripper).”

“Despite the image perpetuated by the media of misery for striking miners’ families at Christmas, and in particular by the well-known film Billy Elliott which presented the father and Billy as alone, cold, presentless and almost foodless, many if not most strikers had a good communal Christmas – and for many it was better than the usual nuclear family-round-the table watching telly, having a traditional Christmas row, with the kids complaining that they haven’t got what they wanted or wanting more…Though undoubtedly there were far less presents for the kids, the excited collective atmosphere and sense of support from others made it, for some at least ”The best Christmas I had”, ”Everyone banded together”, ”Lots of cheap wine flying about – brilliant – really good atmosphere” as various miners put it on the BBC’s 20th anniversary programme.”

From “Theme pubs…”:

“On January 3, 1914, in the city of Juarez, [Pancho] Villa signed an exclusive contract with Mutual for the sum of $25,000. It was also contractually agreed that Villa would do his best to win all his battles in sunlight and to forbid the presence of any other rival cameramen on the battlefield! Aitken also stipulated that in case Mutual did not succeed in shooting enough suitable material during the actual battle, Villa would guarantee to re-enact it the next day before the cameras.” (Quoted in ‘Spectacular Times; Cities of Illusions.)

A pathetic parody of … repressed desire was recently played out on the 15th anniversary of perhaps the bloodiest picket line conflict of the Miners Strike; the Battle of Orgreave was re-enacted near to the original site. Filmed for Channel 4 TV by a Hollywood director, and with ex-pickets and cops from the original battle as extras (but ‘real’ actors playing the ‘heroes’ of the event such as Arthur Scargill – typically bourgeois history as the history of leaders), the event was painstakingly reconstructed from media footage of the time. As always, once the event is safely far enough in the past, the media that acted in its own class interests by lying and distorting the truth in the real time of the class struggle, feels confident enough to now reveal a somewhat more truthful version of events; now that it no longer has any consequences. This is a sure sign of the ruling class’s confidence that these are dead issues, definitively resolved in their favour. They want us to believe that class struggle is a thing of the past. Again, the colonisation process at work; get the defeated to dramatise their defeat as entertainment for the victors. Despite a bit of temporary flattering attention and extra pocket money for the locals, who really gains from this farce? No one but the ruling class and their media. The claims that the event was therapeutic (or “healing”) for some are predictable – but what does it help them come to terms with? Only the acceptance of their defeat and all its consequences since.

This filmed re-enactment follows in the footsteps of other Northern films like ‘The Full Monty’ and ‘Brassed Off’ which (although quite funny) are really just hymns of praise to the new entrepreneurial economy that smashed the miners and others and replaced their solidarity with the Thatcherite ‘get on your bike’ selfish individualism. The sermon is that redundant industrial workers should move with the times and reinvent themselves as cultural entrepreneurs, giving a positive, if unrealistic, inspirational message to the post-industrial workforce.”

From “The End Of Music As We Know It”:

“The Wall On The Screen Guarantees The Walls In Your Life: That the film of the song of the actually lived reality, Pink Floyd’s The Wall, presents the riots as macho, racist and fascist-inspired, even to the point of subtly suggesting a comparison between the anti-hierarchical violence of the riots and the hierarchical violence of World War II, shows how the more sophisticated purveyors of culture are shit-scared of any real and direct attacks on the walls of the prison. They only articulate the rebellions and frustrations of their possible consumers in order to preserve their lucrative niche; a niche threatened by any genuine rebellion from those whose consumption habits they are financially and socially dependent on. When the film first went on release, Top Shop in London’s shopping concentration camp, Brent X, advertised school uniforms placed on sexy plastic models who stood in front of a polystyrene brick wall with the words “We don’t want no education” on it. The blatant nature of this contradiction reveals in a crude form the contradictions of all spectacular pseudo-rebellion, ‘rebellion’ which tolerates the commodity system whose misery engenders rebellion. Disgust with this world (in this case, school, the conditioning factory which prepares kids for the boredom-inducing sacrifices of the commodity system) is used to sell commodities (school uniforms) which can only reinforce this disgust…But the contradictions of being insulted by mere rebel images all too often explode into reality: like the kids who tore up the cinema seats in the fifties after watching Presley’s Jailhouse Rock.”

And “Moore is less” is about Michael Moore’s Fahrenheit 9/11 movie.

Note added 8/9/13: The film « Traité de bave et d’éternité » by the Lettriste Isidore Isou is interesting, and one can see the influence it had on Guy Debord’s first film “Hurlements en faveur de Sade” (http://www.dailymotion.com/video/x5dzg_guy-debord_shortfilms)

Leave a Reply