a strange correlation between the collapse of life and a culture that tyrannises life

Written (by me): end of 2001

“Crossroads is about real life…yet for many it’s more important than their own real life”

“But what is ‘real life’?”

“Aaah…yes…well…blah blah “(mumbles of general confused questioning)

–Radio discussion, 12/7/82.

****************************

“At a time when life itself is in decline there has never been so much talk about civilisation and culture. And there is a strange correlation between this universal collapse of life at the root of our present-day demoralisation and our concern for a culture that has never tallied with life but is made to tyrannise life…”

– Antonin Artaud, The Theatre & Its Double

Soaps are the vicarious community of the isolated individual, the risk-free fake family consumed by highly stressed real families everywhere. The vacuum created by the increasing absence of genuine community is supposed to be filled in this society by the consumption of fictional communities. If we’re attracted to soaps it’s because they tease us with an exaggerated version of our desire for a constant flow of contact and excitement increasingly absent in reality

The less people work and live in the same locality, let alone live and work with their neighbours, the more this fantasy ideal is portrayed in the representations of community.

The more anonymous and superficial our contact with our neighbours is, the less information we have to gossip about them, the more one ‘knows’, and can gossip, about the fictional characters in Eastenders, The Archers, Brookside or whatever.

The less our interest in guessing the development of our friends’ lives, the greater our attraction to the abstract game of predicting what’s going to happen to that character that millions of other spectators are trying to guess about.

The more threatening and discomforting the streets become, the more consoling it is to consume fictional conflicts in the safety and comfort of our misappropriately-named ‘living’ rooms.

The more slow-plodding our real lives are, the more fast-paced the unfolding of the plot lines in soaps become: things that would normally take a year to develop in real life, take a week or less in the soaps (except pregnancies – these take 15 months at least).

At the same time they give us a dramatic view of misery which makes our own trivial miseries apparently far less in comparison. And, of course, the underlying message is “Who the hell is interested in your petty miseries anyway?”. Fiction is stranger than truth, and so very much more interesting.

The writers of soaps, and the pop psychologists who valorise their compensatory function, know most of this and, in a less developed way, discuss this all openly. But they put a positive gloss on it all, along the lines ideologised by the Economy – supply and demand. “Community is dead, yet the demand for community continues, and we supply it”. The Independent on Sunday (4/3/2001) wrote: ‘…Dr. Aric Sigman, a consultant psychologist, says soap operas fulfil our need to belong. Despite the flexibility offered by cable channels and video recorders, most viewers still turn up to watch at the hour the broadcaster decides they should. “People are more alienated than ever. One way to feel as though you are part of a common experiences is to know that you are watching the same programme at the same time on the same day as everyone else.”…’. Culture always consoles us with a fantasy representation of what the commodity economy, of which culture is a part, represses in reality – above all, representation in the form of the illusion of community and artificial excitement. To justify this is to repress the only sane need left for us – the need to struggle for real life community and excitement, and the need to recognise the fact that real life community and excitement only exists in this struggle.

In their modern sense, soaps began in the 40s in America as part of daytime telly, sponsored by soap powder companies who, so characteristically charitable, generously provided housewives stuck at home with a well-cleaned window onto their increasingly absent community. However, the original “soaps” – Dickens’ serialised “Pickwick Papers” – originated from the mid-19th century. It’s not surprising that they became most popular at a time when millions of people were forced by brutal capital accumulation off the land into the grim cities where their neighbours were unknown to them: Dickens, so characteristically chartiable, generously provided them with something to talk about (though this was confined to the literate and those who listened to them reading out loud in pubs or wherever). Significantly, Dickens’ book became especially popular when he introduced a cheerful working class character into his serialised novel, virtually unknown in the English novel up till then. The role model of the ‘good’ worker has developed beyond simplistic stereotypes since the 19th century however: today, the sophisticated cynical spectator expects more complex and contradictory characters that mirror some of their own contradictions, without, of course, revealing the material basis of these contradictions in the class nature of society.

*

In the past, The Archers was first broadcast as part of the Ministry of Farming and Fisheries advice to farmers, and it still retains an adviser from the Ministry of Agriculture. Nowadays, the more welfare cuts hit into social services (one of the sectors of society most permeated by an ideology of community) the more the soaps provide social work and psychological advice on the cheap: what to do with an alcoholic husband, what squatting rights are there, the problems of teenage mothers, what bankruptcy entails, what to do if the police find out you’ve hired a hit-man to kill your husband, etc. – all the usual things you would’ve talked about with the Citizens Advice Bureau or a therapist, but there’s a waiting list as long as your arm, or you’d have to pay through the nose or whatever. The less people are able to deal with the mounting difficulties in their lives, the more the soaps step in with exaggerated and neatly over-simplified versions of their own predicament, and simplistic solutions, or, at least, resolutions to them (story-lines eventually have to come to an end, unlike in real life). Well, did social workers ever do any better? (at best, they just provide a talking shop for the most part, since any real resolution of the contradictions of daily life would involve a radical attack on the objective basis of our misery – the State and the commodity economy it manages). It’s significant that various government ministers have suggested ideological story-lines for the soaps, particularly Eastenders: e.g. benefit fraudsters getting caught and punished, the dangers of truancy etc. However, scriptwriters have apparently resisted such hints, preferring to maintain an appearance of independence from government interference (however, on Grange Hill they had an adviser from the Home Office keeping an eye on their “just say no to drugs” storyline). They don’t need to be told what to write, since, being part of the well-paid professional Middle Class, they spontaneously defend the status quo by preaching the Wages of Sin to those who might stray from the straight and increasingly narrow. In fact, using soaps as a method of imposing images of normal community is probably more effective in maintaining an ideological attachment to ordinariness than the more obviously manipulative aspects of the media, such as the news, which are more often dismissed as propaganda, and certainly “boring”.

*

The most consistent content of soap operas is The Secret. Especially sexual secrets. In daily life, up until the 80s, maybe 90s for some, there was always a strong current of rebellion that refused to keep secrets between friends and lovers. Jealousy was something that had to be struggled against and in any case, hiding your other love relations was no way to treat a lover with respect, either the ‘secret lover’ or ‘the other half”. Then perhaps it was because there was a margin of freedom and sanity in life that stopped you going too far over the top with jealousy. And made you realise that keeping secrets could only make things worse. Not now apparently. And this is reflected and reinforced by the images of normality, the models of correct behaviour, in soaps. Keeping secrets is unquestioningly acceptable because anything other than monogamous property relations is unquestioningly taboo and therefore has to be punished by the misery wrought by The Secret eventually coming out, the spectator titillated by the expectation that it will eventually be revealed. In this vicious circle sexual relations outside the central couple are considered ‘cheating’ because they reflect a world which has lost its will to struggle against the ideal of monogamy, an ideal that demands that ‘cheating’ be kept private, secret, separate. The show of normality must go on.

*

“The spectacle is a drug for slaves. It is not supposed to be taken literally, but followed at just a few steps distance; if it weren’t for this albeit tiny distance, the mystification would become apparent” (Internationale Situationniste).

There are some soap stars who get attacked in the street because the character they play has done something disgusting. Others write to a character in a soap, like an adult “empathetic” version of kids writing to Santa Claus, expressing sympathy with their plight, as if this was a True Story. This society presents these aberrations as something fundamentally in contradiction with ‘normal’ responses, which explicitly or implicitly are evoked as “healthy”, a positive contrast. But the crazies who punch a soapstar for something they did on the show are not the product of societies’ failure but rather are the excessive product of its success: the colonisation of people’s lives by lies and fiction. Though these spectacles are a drug for slaves who don’t want to admit they’re slaves, they aren’t meant to be taken literally, but followed at a few tiny steps distance – it’s ok to get obsessed but only in moderation. People aren’t meant to be fixated on one specific aspect of culture but are meant to be a little bit into an enormous variety of fragments of culture (positively appreciating, superficially criticising, moralistically dismissing this film, that play, this TV show, that pop song, this football team, that opera, etc), which added together, take up as much thought, conversations and time as the obsessives take up on one specific bit of culture.

In obsession, the mystification becomes absurdly apparent – taking this particular spectacle literally, being unable to distinguish between fiction and reality….the madness of hitting someone because of what’s meant to be ‘just’ a story. But the truth is in the mad exaggerations: culture, diluted or concentrated, is the mystification. Culture, like all empires, colonises the repressed and alienated individual, whilst hiding the miserable history of this repression and alienation. That’s why it’s permissible for the professional mystifiers, those mad on power, to play up to these obsessions. Tony Blair once raised in the House of Commons the problem of the imprisonment of Dierdre, a fictional character in Coronation Street, after The Sun had campaigned for her release. There’s something on the edge of madness in this crudely demagogic populism. Certainly this pathetic “I’m just an ordinary bloke like you” crap hopes to hide the semi-psychotic insanity of running the capitalist system. Likewise the support of famous soap stars for competing political gangsters at election time serves to hide the brutal mad system they run.

There are good reasons for attacking soapstars. They invariably play working class characters but live, in reality, in the posher parts of town. They get the poor to identify with them with their stories of being strapped for cash, but in reality often earn over £2000 a week. 3 or 4 years ago, Sid Owen, the guy who played Rikky in Eastenders, complained about some young blokes trashing his Porsche – “It’s just resentment”. The rich invariably reduce anger, hate and disgust towards them to the caricature “resentment” as if our only complaint is that we’re not rich. But it’s patently obvious that it’s hardly resentment that describes people’s feelings towards those who can’t act but know how to crawl to the right people. In daily life, those at the sharp end have to learn how to act far more subtly than some crass actor, and with a great deal less pay, though they have a bit more satisfaction in conning those in authority than any professional actor ever had from the endless flattery they get from this world.

*

Perhaps in reaction to the utterly unrealistic “realism” of fictional soap operas, the organisers of ever-more intensive buzzes necessary to keep us ever more intensively distracted from the ever increasing insanity of the Economy came up with the idea of True Life soaps – in particular, Big Brother. Gripping stuff. Even when they’re cheap and boring, they’re fascinating. After all, these people are REAL and living a real life conflict – the conflict of simultaneously trying to bond with and betray perfect strangers. Essentially the conflict is between trying to act nice and honest for the cameras whilst secretly only thinking about how to turn that nice honest role into fame, into their career, whilst nicely and honestly undermining their opponents, being one-up in the nice honest image stakes with their eye to a nice honest small fortune. But the aim of the ruling show, and the constant spectacularisation of this perfectly strange world, is to make this shoddy, sordid and outright vicious conflict appear to be a bit of a laff.

The great detective game is to psychologise this conflict. Above all, Big Brother gives the spectator the chance to play the role of amateur psychologist. The professional psychologist has the pretension of being a scientist of peoples’ personalities – but essentially only of those aspects of people’s personalities which people have been forced (and have often chosen) to be respectful of – the false choices capital brutally represses us with, a respect for which often drives such people to go to a psychologist in the first place. The psychologist, amateur or professional, maintains a hierarchical separation between themselves and those they are psychologising, as if they are not part of the situation. They look at individuals and situations separated from the remotest critique of the historical social contradictions these people live out, particularly the changing development of social relations mediated by roles and images produced by the commodity economy.

Whilst their feeling of immediate participation in this show is experienced at home, usually alone in a family, it is shared with others, like with other bits of culture, as a conversation-piece – at work, in the pub or wherever, and it is here that everyone has the chance to psychologise, feeling more at ease discussing the stupidities of real people than those of the characters in fictional soaps. Since nowadays all reflective reason other than that submissive to the “realism” of this mad world has been repressed in practice through the intensifying defeats of the class struggle, psychologising is one of the major growth areas when it comes to people’s need to reflect. Such reflection, under the weight of this repression, has been reduced to merely of what is: it accepts the appearance of everything that is described and the inevitability of this shallow surface behind which there is seemingly nothing worth reflecting on. In distracting people from the fact that they’ve been reduced to the level of bored rats squirming in a cage with the fascination of watching other human beings reduced to bored rats squirming in a cage programmes like Big Brother mirror the most reactionary and ahistorical branch of psychology – behaviourism, which partly developed from the study of rats in a cage. Whereas psychoanalysis at least looked at individuals’ histories of repression in relation to their family upbringing, even this narrow notion of the past was excluded from behaviourism (which has always had no pretensions other than “curing” people by making them adapt to an incurably sick world). Virtually all history is excluded from soaps (true or fiction). Everyone acts in a political vacuum, lying to or back-biting each other in the war of each against all, or finding friendship and love despite it all, in some self-enclosed eternal present abstracted from both the mildest political references (and often even from any reference to the contradictions of their childhood). Critical politics hardly even lingers in the background, as it did a bit in the 80s in soaps. Apart from references to the trashing of GM crops, for example, in The Archers, there’s hardly any critical stance nowadays that this society deems worthy of co-opting. All the better to allow dominant politics to surreptitiously push its’ secret moralist message, often in a psychologistic form.

In Big Brother, the masses of spectator-voters are given a vote on whether someone gets kicked out of the house or not – a vote that stirs up far more enthusiasm than voting for a politician – a milder, but more separated, version of the thumbs down the mainly poor could give to gladiators during the Roman circuses. Let no one dismiss changes in the spectacle – like Big Brother – as just another novelty. Like The Weakest Link, such “games” undoubtedly reinforce people’s acceptance of the brutal humiliation that lies at the heart of daily life. For all the reasons mentioned, but especially this last more general one, it was rightly considered sick by many: if you get used to that you get used to anything.

In France they haven’t yet quite got used to anything. The French equivalent was greeted with denunciations of its totalitarianism, its disrespect for human dignity, its public humiliation, its voyeurism. Though some of this sounds like classical French bourgeois philosophy, this perspective does carry within it the germ of a genuinely revolutionary desire which is still there. Which is one reason why some protestors dumped rubbish bins in front of the offices of the commercial channel that broadcast it, protesting at “trash television”, whilst riot police launched tear gas against 70 protestors who tried to storm the loft area it was being broadcast from. When I told someone this in the pub she said, “They should get a life!”, referring to the protestors, not the show or its spectators. Typical London – everything upside down, inside out, wrong way round.

*

Big Brother was a commercially organised plagiarism of people who have internet cameras all over their house and spend their lives performing to those billions of people who watch it avidly 24 hours a day – give or take a few billion. The desire for 15 minutes of fame, or at least to valorise ones life by turning it into a show, and for this show to be the mediation with the world, ones idea of ‘community’ and of ‘unity’, has never been so pathetic, and so suffocatingly all-pervasive – from kids as young as 7 even. Even me, who’s written this, wants thistext to be, in some ways, ‘famous’. Fame – the desire to be known by strangers in an anonymous strange world is the ambitious careerist distortion of the real desire to have some social effect. It’s seen as a way-out from the central feeling of being on the absolute margins of existence.

*

Whilst British soaps tend to represent the life of so-called ordinary people, American soaps tend to represent the lives of the rich. Some people think that the fact that these ostentatiously vulgar spoilt rich brats are depicted as miserable, vicious and utterly two-faced shows an underlying criticism of capitalism. Yes, if one thinks that Christianity is a criticism of capitalism. The notion of the poor but honest worker valorising himself as morally superior to the sickening fat cats is the superficial critique that the image of the Good Christ has long hoped to represent. The fact that the rich are also not happy is meant to console us for our own unhappiness. That this form of soap has been particularly prevalent in the most rapaciously capitalist and increasingly fundamentalist Christian, country in the world is indicative of its use for capital.

*

In the 60s in Germany, an actor, in some long-running whodunit serial which had mesmerised the nation, revealed, a few episodes before the denouement, who it was whodunit ~ a subversive act which momentarily destroyed the nation’s trance. Nowadays, however, the tabloids reveal a few days before what’s going to happen in this or that soap – who’s going to die, who’s leaving the show, who’s going to get tied up by armed robbers, etc. – so as to get people guessing how or why…All the better to avoid trying to develop the real life practical hows and critical whys of getting out of the stress-mad nightmare that’s already arriving.

*

Some people think that writing about, or talking about, the soaps in anything but a trivial manner is making something more important than it is. Undoubtedly if it’s worth analysing soaps it’s not because soaps are any more worth looking at than any other significant aspect of the poisoned air we breathe.

Of course, we all have to breathe. Our attraction to them is real – it can’t just be turned off by switching to a more educational programme, say by watching animals killing or fucking each other. Only a better life would stop most of us switching them on now and then. After all, soaps are there to compensate us for a sad life. If few of us take them seriously, nevertheless they have sufficient power to fill a few conversations. As an ad for EastEnders says, “It’s what everyone’s talking about”: though this is more a publicist’s wishful thinking, designed to make people feel excluded if they don’t consume the right things, it does also reflect the extent people are mediated by external culture as never before. So if your reaction to this is “Lighten up” maybe you’re right – but let’s get heavy about the things that count, and the things that count are what’s important in this analysis, not the soaps themselves. Looking at soaps is really a pretext here for looking at almost everything. Well, you have to start somewhere.

The essential aspects of this critique, though specifically focussed on soaps, could, with a different content, be focussed on aspects of High Culture. It’s not this or that representation of a living community, aspects of which were experienced in the past and/or could be experienced in a future free society, and are occasionally experienced now, that’s important, but the repression of this possibility and its transformation into mere representation that’s the essential problem – and it’s this that hardly ever gets spoken about. Equally, this is not meant to be a moralcriticism of the audience, of which I am a part: as just kind of mentioned, culture, in whatever form, is the poisoned air we breathe. We all need to breathe but this doesn’t mean we shouldn’t fight pollution and its causes. It’s a question of criticising a real situation that makes people seek out false exits in the form of culture. The hierarchical conflict between High Culture and Low Culture is somewhat archaic as more and more of the Middle Class find ideological justifications for their interest in what was more traditionally Working Class culture, whilst more and more of the working class find usually less pretentious reasons (“I like it”) for their interest in what were formerly Middle Class forms of culture.

The term “philistine”, meaning someone without culture, was a term of abuse invented by the Israelites as ideological support for their military victory over the Philistines, who, in fact, did have a culture. Today, culture is simply a set of rules and forms of expression and behaviour which are imposed externally and hierarchically onto individuals and their interaction. Whilst this was, arguably, necessary in previous societies in order for them to progress, against the reign of the Economy, progress demands the destruction of culture, and the realisation of what is human in these forms of fiction in the creation of a new world. The victorious colonisation and destruction of the distinctive aspects of marginal “cultures” – local, working class, black, etc.- by the market system makes various differences in culture interchangeable: everything gets homogenised and banal (so much so that even saying this becomes a banality, a cynical feeling of impasse that can only be reversed by looking at all the possibilities that were missed and repressed in the past, the chances and risks near and far to break the suffocating weight of banality and trivialisation). So nowadays, trivial hierarchical battles over taste merely provide a subjective rationale for the objective division of labour. Superficial differences in taste and in modes of adjustment to alienation become increasingly central to what makes you ‘better’ (or more ‘radical’, or more ‘cool’ or whatever) than the proletarian-next-door the more social contestation, and the possibility of breaking out of the role of spectator imposed on you, becomes peripheral. Just as racism, wife beating, vicious psychotic attacks, etc. increase the more class solidarity is shattered, so also is there a vast increase in tastism, culture beating, vicious artistic attacks etc. It is one thing to defend your personal taste, it is quite another thing to valorise it, to pump it up, to use it as a way of keeping yourself superior, separate. In the end, ideologising your interest in classical operas as opposed to soap operas (or vice versa) is as irrelevant as the conflict between two soap powders.

“One of the reasons for the stifling atmosphere we live in, without any possible escape or remedy, which is shared by even the most revolutionary among us – is our respect for what has been written, expressed or painted, for whatever has taken shape, as if all expression were not finally exhausted, has not arrived at the point where things must break up to begin again, to make a fresh start”

– Antonin Artaud, The Theatre and its Double.

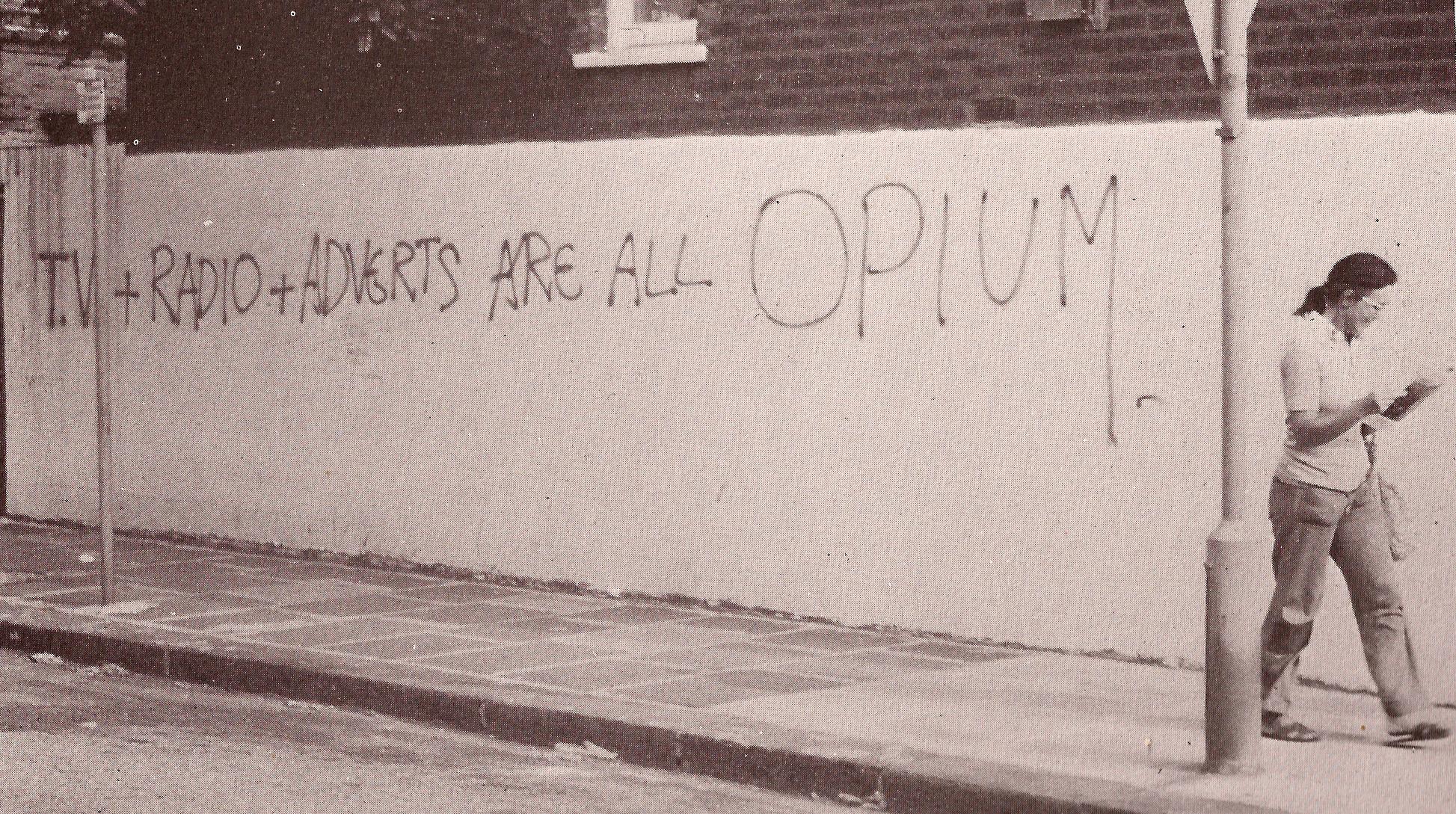

1970s graffiti, Notting Hill

Hits as of 30/4/19: 3125

Leave a Reply