(originally published by me on Libcom Blog)

This is chapter 6 of Larry Portis‘ book French Frenzies.

Larry Portis died on June 4, 2011 near Ales in the Languedoc-Roussillon region of the South West of France. He died suddenly of a totally unpredictable heart attack, at the tender age of 67, almost 68.

The following is an example of the originality of his research, which, despite its academic stance , is full of fascinating facts and insights, which can form the basis for a more proletarian critique of musical forms. Despite all its faults, it’s a really good read. Enjoy!

The Poverty Of French Rock ‘n’ Roll

The advent of rock and roll in France was not a social phenomenon of great depth or importance as it was in the United States or Britain. The abrupt commercial breakthrough of rock and roll in France did not shake up the music industry so much as to create new marketing possibilities. In the mid-1950s, at the very moment rock and roll was upsetting the US music industry, the songs of Brassens and Brel began to find widespread acceptance in France, reinforcing a long literary and musical tradition. In France, the commercial presence of the new music was virtually non-existent until 1958, and for years its production was dependent upon the adaptation of American hits.

It is significant that, although a large market quickly emerged for rock and roll in France, it did not jeopardize the fortunes of established singers as it did in the United States. The careers of Yves Montand or Charles Aznavour did not suffer, as did those of Frank Sinatra or Tony Bennett, for example. Such differences contribute to questions posed about the authenticity of French rock and roll and, later, French rock.

The French Resistance

Are the French less capable than European-Americans or Britons of recreating music of African-American origins? Does the peculiarity of French culture impede the reproduction of a music founded in the alienation of first a racial minority and then a rootless, alienated American population? The explanation frequently offered by French musicians and fans of rock and roll is that there is indeed a cultural limitation in France: the language. In their opinion, the phonetic structure and monotone stress patterns of the French language make the articulation of the emotions, the feeling at the heart of African-American music, virtually impossible.

But this explanation is inherently contradictory. Artists possessing will and talent can overcome problems of technical execution. Most importantly, feeling is not subordinate to technical ability; and, as it happened, rock and roll was successfully performed in France even before it found a large market.

As early as 1956, the writer Boris Vian wrote rock and roll lyrics (under the name of Vernon Sinclair) that were convincingly performed by the singer Henri Salvadore (under the name Henry Cording). These efforts were, it is true, parodies. But they were accomplished with such a degree of competence that they raise questions about the far more technically inferior “products” offered to the public several years later.

Boris Vian occupies a pivotal place in the evolution of popular music in France because he embodied the transition between the immediate postwar renewal of the literary song and the less textually serious rock and roll that followed. Vian was a young darling of the Left-Bank existentialist set who embodied the spirit of the Zazous in every way. Musician, composer, writer, he carried the cause of Johnny Hess and Charles Trenet forward into the 1950s and beyond. He was the creator of a number of songs, such as ‘Le Déserteur’ (The Deserter), “La Java des bombes atomiques, ” (Atomic Bomb Party), “Les Joyeux Bouchers,” (The Happy Butchers), “Je suis snob” (I’m a snob) “Complainte du progrès,” (Progress blues) , ‘Le Petit Commerce’ (Small business) and ‘La Java Martien’ (Martian jump) which combined the seriousness of Brassens with the mockery of Trenet.

Jazz trumpeter and jazz commentator, Vian successfully fused an artist’s sensibility with the analytical acuity of the best literary critics. In “Le Déserteur” (1955), for example, he addresses the President of the Republic, pronouncing himself against militarism and war in the wake of the French defeat at Dien Bien Phu in Indo-China and at the beginning of the War in Algeria. The song was banned from the radio and television. In “La Valse Jaune” (The yellow waltz), (sung by Mouloudji) he offered a challenge to the productivist ethos propagandized in postwar France by proclaiming, “there is too much work in our lives. I don’t like work, but I love life.” In “Les Joyeux Bouchers” (1956), he called into question the eating of meat along with militarism. The refrain in this song used a common expression meaning the fight must he waged without compromise, “II faut que ça saigne,” , literally: “let it bleed.”

In 1956, Vian and Henri Salvadore collaborated in spoofing the new music, rock and roll, which had emerged in the United States. Issued under the name Henry Cording (sounding like “in recording” in French), the songs “Dis-moi que tu m’aime, rock” (Tell me you love me, rock), “Rock-hoquet” (Hiccup rock), and “Allons cuire un oeuf, man !’’ (Let’s go cook an egg, man!) capture the spirit of the more accessible currents of rock and roll. “Dis-moi, que tu m’aimes, rock,” for example, is done in the instrumental style of Bill Haley and the Comets, and Henri Salvadore’s voice resembles that of Louis Armstrong. These recordings are evidence that French musicians possessed the technical ability of producing rock and roll music and singing it in French with original compositions. But the fact remains that rock and roll never emerged in France with the originality that it did in Great Britain. The question is why.

For Boris Vian, jazz musician and translator of American literature, the French public was generally incapable of appreciating American music, which was simply too different in structure to be felt by the overwhelming majority of French people.

In a revealing text written before his death in 1959, Vian defined “rock and roll,” and explained the cultural barrier to its rapid assimilation in France. For him, rock and roll was an outgrowth of rhythm and blues, whose uniqueness, in relation to earlier modes of reproducing the 12-bar blues formula, was that it was a primarilv vocal music relying upon a standardized arrangement. The drummer maintains a steady four-beat tempo in which the stress is on the second and fourth beats. The bass plays a doubled, “boogie-woogie” beat by “slapping” the strings. The instrumental melody is generally reduced to a repetitive series of notes (called a “riff”) that is contained within two bars.

Rock and roll also differed from blues and rhythm and blues with respect to what was sung. Whereas blues lyrics often revolve around double meanings invoking eroticism, in rock and roll this cleverness is generally eliminated in favor of greater simplicity of interpretation. Vian explained: “The erotic lyrics of black blues, often very amusing and almost always perfectly healthy and full of good feeling, have been systematically deformed and exploited by small white bands composed of bad musicians (such as Bill Haley) to arrive at a sort of ridiculous tribal chant, for the benefit of an idiotic public. The obsessive quality of the riff is used to put listeners in a trance.” He goes on to explain that this new music quickly achieved tremendous popularity in the United States because of the sexual taboos in that puritanical country. Rock and roll either channels or releases libidinous energies pent up by a repressive moral code In France, on the contrary, the public is not “paralyzed” by Puritanism and, therefore, has no need of rock and roll.

[Samotnaf note: “Rock ‘n’ roll referred to sexuality in the context of the official denial (and struggle against it) to which its audience was subjected – sex appeared as the principal means of escape from a hostile, miserable world” – Chris Shutes in “Two Local Chapters in the Spectacle of Decomposition”].

If that was not enough, Vian continued, the very structure of French popular music produced a people relatively insensitive to alien rhythms. In contrast to African-American music, which stresses the second and fourth beats, French popular music stresses the first and third beats in keeping with the tradition of French military marches. The French automatically react to popular music in terms of this stress. When the French listen to rock and roll, Vian observed, they mark the time by clapping their hands against the beat! “Indeed”, he concluded ironically, “it seems difficult to induce a trance in listeners who are physically reacting against the beat of the music in question”. [Boris Vian, “Rock and Roll”, in Noel Arnaud, “Les vies parallèles de Boris Vian”, Paris, 18/10/76 (1970), p. 392-393]

A jazz purist, with years of experience playing in trendy clubs on the Left Bank, Vian must have been disconcerted and annoyed as he played his trumpet for merry-makers who heard the music, hut did not listen to it or appreciate it (or, still less, understand it). Not a rancorous man, he simply concluded that it was not their fault; they were constitutionally incapable (culturally speaking) of feeling the music except as the latest fashion. In the end, the only way rock and roll can appeal to the French was to make them laugh; and so he produced a kind of rock and roll novelty music with a primarily pecuniary end in view. This was his job at the Philips recording company.

The man who introduced Boris Vian to rock and roll, record producer Jacques Canetti, has even suggested that Vian may have retarded the reception of the new music in France. When Canetti and Michel Legrand returned from a trip to the United States with some rock and roll records in their suitcases, they immediatelv turned to Vian in the hopes that a market for the latest rage could he created in France.

Vian, the jazzman-intellectual, instantly understood the principle underlying rock and roll, and after some effort managed to instruct some studio musicians on how to go about playing it. It was a great achievement. The songs were catchy, well performed. But, as Canetti recalled, Vian’s rock and roll was a kind of burlesque satire tinged with irony. Here was the problem. The potential market for such material was certainly not the Left~Bank intellectuals of Vian’s circle. The appeal should made to adolescent youth. But Vian was incapable of pandering to them, as Lieber and Stroller, Mortimer Shumann, Doc Pomus and others did with so much talent in the United States. The problem was, as Canetti said wistfully (thinking of missed profits), “young people want to be taken seriously.” Boris Vian’s rock and roll, regardless of its musical competence, amused the intellectuals, hut was shunned by French youth.

The initial response to the question of why rock and roll did not quickly strike a responsive chord with French youth is even simpler than Boris Vian and Jacques Canetti were willing to admit.

As Vian’s and Canetti’s explanations reveal, the emergence of rock and roll in France was primarily a merchandising decision made by representatives of major record companies. This is not to say that demand for it was only an artificial creation; but it is clear that there was no profound aesthetic or social movement dictating the form the new mode of musical expression would take. More importantly, when French youth did begin responding to the new sound, they were especially receptive to the more superficial forms of it.

Part of the problem was that the French were dependent upon the fortuitous events determining which American rock and roll performers appeared in France. Bill Haley and the Comets performed in Paris in 1957 and Paul Anka in 1958. Regardless of Haley’s importance in the commercial history of rock and roll music, these appeammes illustrate the relatively late and meager impact of the phenomenon in France. Whereas blues. rhythm and blues and rockabilly artists influenced the British in the mid 1950s, it is remarkable that the French were initiated to rock and roll by the Canadian crooner Paul Anka.

But it would he begging the question to explain the relative non-receptivity of the French to rock and roll in these terms. Even when Brenda Lee, a performer far closer to the African-American “roots” of the music, appeared in Paris in 1959, her desperate manager could only sell her to the French as a freak thanks to her short stature (although 15 years old, she was billed as a child prodigy in order to increase interest). Five years after the explosive emergence of rock and roll in the United States. and three years after the formation of the Quarrvmen by John Lennon and Paul McCartney, the market for rock and roll was yet to develop in France.

Creating the nouvelle vague

The first rock and roll star in France was Richard Anthony (born Richard Btesh in 1938), and the fact is significant. Anthony was a law student and saxophonist who had little in common with the first generation of rock and roll artists in the United States or Britain. Clean-cut and reassuring in every way, Anthony was nevertheless interested in a new music that he suspected had commercial promise among French youth.

In 1958, working as a salesman for an electrical appliance company, an occupation which excited him far less than “the Anglo-Saxon rhythms” he heard by tuning his radio to foreign stations, he decided to record his voice singing over Paul Anka’s hit, “You are My Destiny.” With his recording in hand, he later explained, “I went to see record producers and told them that I knew a young American living in France who would popularize this Anglo-Saxon music by singing it in our language. I pretended to be an impresario when in fact it was me singing. It should be pointed out that, working as an appliance salesman, I knew how to place a product.” [François Jouffa, Jacques Barsamian and Jean-Louis Rancurel, Idoles Story, Neuilly, Editions Alan Mathieu, 1978, p.6)] . Anthony obviously made a positive impression. Pathé Marconi, one of the most important record companies in France, contacted him quickly. One week later he made a studio recording of “Tu m’étais destinée,” which was released in May 1958. However, it wasn’t until the release of Anthony’s third record, “Nouvelle vague” (New wave) that his entrepreneurship paid-off.

“Nouvelle vague” has been called the first “yé yé” hit, the first of the “new wave” of youth-oriented songs inspired by American rock and roll. Although the lyrics of the first French rock and roll songs were adapted into French from the American originals, it was good form to punctuate the verses with an enthusiastic “yeah!” pronounced as “yé [yay]” “Nouvelle vague” was a copy of “Three Cool Cats” and it is far from qualifying as a rock and roll composition. What it did represent was a new spirit in French popular music, which corresponded to the aspirations of the first post-war generation of French youth.

There was something changing in France, which affected not only youth hut also young adults. The expression “new wave” was used at the time to denote the emergence of a new school of French cinema represented by Jean-Luc Godard, François Truffaut, Alain Resnais, Louis Malle and others.

Godard’s A bout de souffle (Breathless), also released in 1959, contained all the elements announcing the new sensibility. In this filim Jean-Paul Belmondo’s calculated “cool,” copied from American movies (Humphrey Bogart and James Dean) took the form of an anti-social individualism which diverged considerably from the socially responsible anarchism supported by Brassens, Leo Ferré and others, whose political and social consciousness was formed by the combined influences of the Popular Front of 1936 and resistance to the Nazi occupation, which were not experienced by the new generation. Belmondo’s co-star, Jean Seberg, played an American in Paris who sold the New York Herald Tribune in the streets and cafés, thus symbolizing the American presence in post-war France.

The French-Swiss director’s juxtaposition of Belmondo’s Gallic posing and Seberg’s Anglo-Saxon impenetrability symbolically describes a France in which American cultural imperialism was giving birth to new values. Ostensibly a free spirit, a latter-day Zazou, in fact, Belmondo is manipulated by market forces and cultural codes unknown to him. After stealing a Cadillac automobile, and killing a policeman, he is fingered by the enigmatic Seberg, who watches impassively as he dies on the pavement, shot in the back by the police, imitating Humphrey Bogart to the end.

Godard’s description of a new generation was compelling to French youth. The image of irreverence, of irresponsibility, of the simple desire to have fun conformed to the lyrics of Richard Antony’s “Nouvelle vague,” which told the simple story of three boys in a MG automobile who were suddenly captivated by three girls who were singing an Elvis Presley song. The English sportscar, the nonchalance of the boys who dangled their legs over the doors of the convertible, and the frivolity of the courting ritual were all signs of a shift in sensibility accompanying the emergence of a consumer culture in France. The stress upon novelty and the ephemeral encouraged by an intensified trend towards commodity fetishism was hammered home by the hypnotically repeated refrain: “Nou-velle vague, nou-velle vague.” A real youth movement began to emerge, heavily influenced by American models, but nevertheless expressive of a new generation and holding out the promise of considerable commercial exploitation.

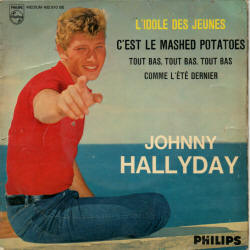

In the United States, the beginnings of rock and roll were in the spontaneous fusion of African-American rhythm and blues and European-American country and hillbilly music. In France, the beginnings of indigenous rock and roll lay in the efforts of individuals to convince record producers that such a music should he created because the market already existed. In the United States, the music was the product of real social forces, in France it was primarily a commodity created by merchandisers. In the United States it was a social phenomenon. In France it was a cultural epiphenomenon. In the United States, legions of performers also followed the lead of artists whose cultural and social existences were sources of primary musical inspiration, but in France the artificiality of this kind of aesthetic appropriation was coupled by the ultimate necessity to conform to established social relations and musical culture. The dynamics of this process are amply illustrated in the career of the “French Elvis Presley” – Johnny Hallyday.

Born Jean-Philippe Smet in Paris in 1943, the future Johnny Hallvdav was an early customer of the Golf-Drouot , a former indoor miniature golf course on the corner of the boulevard Montmartre and the rue Drouot converted into a club for teenagers by Henri Leproux in 1957 (it is now a McDonalds restaurant). At the Golf-Drouot the latest records could be listened to on a jukebox as young people mingled and danced, free from parental or adult supervision.

This breaking away from parental control is an important factor in the attraction of rock and roll in France. Although the “moral revolution” of Philippe Pétain no longer existed as a political and social program, France was nonetheless a bastion of conservative moral codes and the patriarchal family. In evaluating the attitudes of French youth in the 1950s and 60s, it should be kept in mind that women had the right to vote only since 1946 and that wives could not obtain a checking account without their husbands signature until 1966. In such a cultural context, the furor aroused by the new attitudes symbolized in Godard’s Breathless is understandable.

Like the character played by Jean-Paul Belmondo in Godard’s film, Johnny Hallyday was typical of post-war youth, detached from the experiences of the economic depression, war and resistance. Identification with American music was important in giving French youth the confidence necessary to oppose prevailing moral codes.

The young Johnny Hallyday was a privileged person in this milieu. Adopted by a cousin when he was very young, his “stepfather” was an American acrobatic dancer who toured Europe. The world of show-business and American musical culture were, therefore, familiar to Hallyday, whose height, blonde hair and regular features distinguished him at a time when James Dean was the model of American cool. Nicolas Ray’s film, Rebel Without a Cause was released in France in 1955 with the title translated as La Fureur de vivre , the rage to live. The handsome and carefree Hallyday often brought a guitar to the Golf-Drouot, where he sang Amerian hits and pretended to be an American in order to impress his peers, especially the girls.

In December 1959, he performed on stage at the Marcadet Palace , catching the attention of a young songwriting team (Jil et Jan) who introduced him to a record producer, Jacques Wolfson of Vogue. In March 1960, Hallyday’s record “Souvenirs, Souvenirs” was released and became a hit. It was this success that convinced record companies in general that there was a lucrative, teenage market for the new music.

The rush was on. The French record companies were now as desperate to sign rock and roll singers as the American producers had been in 1955. The Golf-Drouot became the talent scout’s mecca. Its proprietor, Henri Leproux, explained years later how “all the artistic directors (of the record companies) came looking for the rare bird who might be another Johnny Hallyday. Any little guy who got up on the stage at the Golf-Drouot and who could sing a bit was in a recording studio a few days later.” [Ibid., p.11-12]. It was this combination of enthusiastic teenagers anxious to imitate their American idols and record companies hoping to profit as quickly as possible, that created French rock and roll.

Within a matter of months, the first wave of the new recording stars was signed-up. Eddy Mitchell (Claude Moine) worked at a bank across the street from the Golf-Drouot . He became the singer of the group Les Chaussettes Noires (The black sox) signed by Barclay. Jacques Dutronc was the guitarist of El Toro et les Cyclones signed by Vogue (El Toro was a stockboy at the department store Galéries Lafayette , down the street from the Golf-Drouot . By the end of 1960, the record companies recorded other amateurs, such as Frankie Jordan (Claude Benzaquem) and Sylvie Vartan, who also became stars.

The artistic credentials of these new performers were meager. Jordan was a dental student who dabbled in the new music in his spare time. Vartan was the sister of the studio orchestra leader Eddie Vartan and was signed because the promoter, Daniel Filipacchi, thought she was cute.

Non-musical factors had to be used in the selection of both artists and song material, for the record producers had absolutely no idea of what constituted talent in this realm of musical creation. Ultimately, however, the formula for success and quick profits was deceptively simple. The producers merely read the American trade magazine Cashbox every week. In this way they determined which American hit songs should he adapted into French. Years later, Frankie Jordan recalled that Johnny Hallyday was generally given the number one hit on the American charts, Richard Anthony received the number two, and the Chaussettes Noires , himself, and others scrambled for what was left.

Another indication that the impulse behind the emergence of French rock had little to do with the aesthetic inclinations of French youth was the role played by commercial advertising. The Chaussettes Noires became the most popular rock and roll formation in France thanks to the Stemm stocking company, who used the group to promote its line of black sox with colored borders. For each pair of sox sold, a free entry to the Golf-Drouot was given to the customer. Thus, the Chaussettes Noires were created as a promotional gimmick concocted by Barclay Records, the Sternm company and the Golf-Drouot. Another of the three or four seminal French rock and roll groups, Dany Logan et les Pirates, was promoted by Barclay with funding from the French Milk Producers Association. Their big hit was “Je bois du lait” (I drink milk, slang for “I love it”). And this was only part of a general merchandising phenomenon. A consortium of record producers, impresarios and industrial-commercial interests, in fact, created the whole scene. [See Henri Leproux, Golf-Drouot. Le temple du rock, Paris, Rober Laffont, 1982, p.52-53, 58-59, 123-124.]

Such commercial exploitation is not surprising. It has accompanied every change in popular music from Champagne Charlie in nineteenth-century England to Michael Jackson and beyond elsewhere [See Larry Portis, Soul Trains: A Peoples’ History of Popular Music in the United States and Britain, College Station, Virtualbookworm, 2002]. What distinguished the inception of rock and roll in France was that the merchandising preceded the modification of popular culture. In France, financial interests did not simply exploit the performer-artists, they created them. For example, the singer Sheila was selected after the promoter Claude Carrère decided that there was room for a female voice among the existing stable of new singers.

Did something of musical value emerge out of this blatant huckstering? It would be unfair to say no. But it would be difficult to deny that for several years there was precious little in rock and roll à la française that could be seriously considered creative. Early French rock and roll was derivative to the point that the absence of originality was almost total.

Still, the enthusiasm of the young performers could not be denied, and this was what they communicated to their fans. No one, neither the artists nor their public, considered Johnny Hallyday to be the equal of Elvis Presley, Eddie Mitchell of Eddie Cochran, or Dick Rivers (Hervé Fornieri, singer of the Chats Sauvages (the wild cats) of Gene Vincent. A few of these early French rock and rollers developed into competent and even interesting singers and composers. Hallyday, Mitchell, Rivers, Dutronc and many others had good voices and must he distinguished from others, like Vartan and Sheila, who were more completely creations of record producers and who had little feeling for the music. What they all had in common was the knowledge that they were imitators.

The predominately “artificial” beginnings of rock and roll in France posed no artistic challenge to the record industry as it did in the United States. Consequently, to those French singers and musicians attracted to rock and roll, it left a deeply ingrained inferiority complex about their capacity to recreate the new music. The contrast between the French and British experiences in this regard could not be greater.

The superficiality of early French rock and roll also must be understood in terms of the rapidity with which it was introduced to the general public. Although a first few ventures were launched as early as 1958 (Richard Anthony and Danyel Gerard), the year 1959 still belongs to the prehistory of French rock and roll. The fact that rock and roll had not yet penetrated the popular music market is illustrated by the kinds of records released. For example, two records of that year that had the “feel” of the new music were Claude Piron’s “Docteur Miracle,” a cover of the American novelty hit “Witchdoctor,” and the jazz guitarist Sacha Distel’s “Scoubidou.” It is not really until the summer of 1960, after the release of Johnny Hallydays “Souvenirs, Souvenirs” in March 1960, that the new music clearly began to impose itself.

Even then, the other prominent performers did not record or have their first successes until the end of 1960 or the beginning of 1961. For example, Frankie Jordan did not record until December 1960, and the most popular of the groups, Les Chaussettes Noires, did not have their first hit until January 1961. The other famous group, Les Chats Sauvages, did not release their first record ( “Ma Petite amie est vache,” – My girlfriend is mean – a cover of Presley’s version of “Mean Woman Blues”) until spring 1961. These dates are important because at the very moment French rock and roll had built up a certain momentum, by Spring 1961, the record industry began to impose different artistic criteria in response to new trends in the United States.

It took US record producers several years to blunt the force of the new musical synthesis. It was not until 1961 that commercial rock and roll in the United States, created by individual performers heavily influenced by countrv, blues and gospel, was largely replaced by a simplistic dance music made by instrumental and vocal groups under the direction of entrepreneurs. In France, with their policy of blindly following the lead of the American hit parade, French producers immediately introduced the Twist, the Madison, and other dance crazes, compelling rock and roll performers to adapt to the new trend. By Summer 1961, the Twist already dominated the market.

The result of this marketing strategy was that the era of rock and roll in France was virtually over before it had a chance to really begin. On September 21, 1961, the first of the “yé ye” magazines, Disco Revue , appeared. When the more famous magazine, Salut les Copains (Hello buddies) first appeared in July-August 1962, French rock and roll was already transformed into the commercial “variety music” that retained only the tempo of rock and roll and the use of amplified instruments. The Big Beat had largely disappeared.

In this new context, it is not surprising that the original rock groups, Les Chaussettes Noires, Les Chat Sauvages, Danny Boy et les Pénitents began to have difficulties. According to Claude Jouffa, the end of 1961 was the “beginning of the end for French rock and roll groups.” The reasons were, however, multiple. To the change in fashion must be added the internal rivalries that frequently emerge when an artistic association of young people suddenly comes into possession of wealth and celebrity. Eddie Mitchell left the Chaussettes Noires in part for these reasons, but also because he was drafted into the army. The limited musical capacity of these performers was another factor. Two members of the Chaussettes Noires, for example, were replaced whenever the group recorded. This situation was far from exceptional, and Dick Rivers of the Chats Sauvages took pride in the fact that his group was virtually alone in its ability to record without the use of studio musicians. A certain rivalry existed between the Chaussettes Noires and the Chats Sauvages that probably contributed to the excitement, but already in 1961 Eddie Barclay, producer of the Chaussettes Noires, lured Willy Lewis, drummer of the Chats Sauvages , away from his group in order to weaken it. A few months later, Dick Rivers himself left to go solo.

French rock and roll performers were not allowed to develop their abilities, hut the market for the new popular music was cultivated assiduously. The organization of concerts by a highly integrated popular entertainment industry was a prime method in this regard. The first major rock “festival” was organized by the radio station Europe 1, the major promoter of French rock and roll music, and held on February 24, 1961 at the Palais des Sports. The star performers included Johnny Hallyday, Les Chaussettes Noires , Frankie Jordan, the American singer Bobby Rydell, and the Italian rock and roller Little Tony. The second festival was held five months later at the same location, set-up by the record company Pathé-Marconi and featuring Richard Anthony. These concerts were important not only in that they illustrated how successfully the music industry was able to cultivate the new market, but also because they revealed how a new youth cohort used the music as a means of cultural expression.

The pandemonium was such at the first concert that the authorities saw fit to ban them altogether. The financial interests involved overcame this official opposition, but the spectators’ violence continued. In June 1961, Richard Anthony, the French Paul Anka, not known for his incitation to riot, was struck by a beer bottle during his first number and was led away with blood streaming from his face. In November 1961, when the transplanted English-American rocker Vince Taylor appeared with the Chats Sauvages at the Palais des Sports , there was a veritable riot during which rows of seats were destroyed by the “blousons nojrs” (leather-jacketed gang members).

Such events quickly became the stuff of legend, especially as the first phase of French rock and roll passed quickly. When the magazine Disco Revue organized a festival on January 27, 1963 featuring Gene Vincent, nostalgia was already in the air. Danny Boy was without his Penitents, the Chats Sauvages were without Dick Rivers (replaced by Mike Shannon) and the Chaussettes Noires were left without Eddie Mitchell, drafted into the army in March 1962.

The climax of this cultural and commercial evolution occurred on June 22, 1963 with the outdoor concert organized by the radio station Europe 1 on the occasion of the first anniversary of the magazine Salut les Copains. Called “La Nuit de la Nation” (because it was held at the Place de la Nation), the concert foreshadowed such events as the funeral of Brian Jones and the Woodstock concert (both in 1969) in that the number of persons attending went beyond all expectations. 200,000 people filled the huge square. There was some fighting and destruction of property, and once again division among the authorities about the desirability of rock concerts and rock and roll music in general. On the one hand, established economic and political elites worried about the increasing alienation of youth. On the other hand, the entertainment industry worked aggressively to enlarge its market and to exploit the energies stimulated by their promotion of the music.

The yé yé Years

It was the famous “yé yé” phenomenon during the years 1962-66 that best symbolizes the almost total control exercised by the music industry over the direction of this type of popular music in France. A star system had been carefully established, based upon the creation of singing “idols” whose every move was controlled by managers and producers. Johnny Hallyday was the model in this regard. His ambition, sense of accommodation, and willingness to accept the advice of Lee Hallyday, his cousin and manager, set the tone for other artists.

The dependence of performers on the big companies is not, however, due only to their subservience. The centralization of industrial control in France has not allowed the incubation of individual talent in small recording companies as in the United States. The yé yé period was a unique phase in the consolidation of the French recording industry’s control through the modification of cultural sensibilities.

The sociologist Edgar Morin claims to have invented the expression “yé yé” which he used for the first time in an article in the newspaper La Mantle appearing after the famous “Nuit de La Nation” in June 1963. For him, the phenomenon was a kind of mass hysteria through which youth expressed a desire for community and emotional release in an increasingly “rationalized” society. The cry “yeah” repeated in many rock and roll songs, pronounced “yay”, was a literal affirmation of the desire for immediate gratification of youthful impulses. It meant: “we are young and want to live life to the fullest.” Morin recognized that in France the phenomenon was weaker than elsewhere: “in France, the explosive phenomenon of rock has been domesticated, whereas in the United States and in the Nordic countries it was much more violent.” [quoted in Jouffa, op. cit., p. 58] .

[Samotnaf note: re. Edgar Morin – in the Situationist International’s post-May 68 analysis of the movement at that time “The Beginning of An Epoch”, they say the following about him: “The old apes of the intellectual reservation, lost in the muddled presentation of their “thought,” only belatedly started to get worried. But they were soon forced to drop their masks and make fools of themselves, as when Edgar Morin, green with spite amidst the hooting of students, screamed, “The other day you consigned me to the trashcan of history . . .” (Interruption: “How did you get back out?”) “I prefer to be on the side of the trashcans rather than on the side of those who handle them, and in any case I prefer to be on the side of the trashcans rather than on the side of the crematories!” ]

There is little doubt that yé yé represented the reduction of popular music to astonishingly low levels of creativity and musical ability. Singers like Sylvie Vartan, Sheila and France Gall were often incapable of singing in key, possessed voices devoid of real expression, and obviously had nothing personal to communicate.

In November 1962, Sheila (Annie Chancel, named after the song “Sheila” by Tommy Roe, covered in France by Lucky Blondo) achieved immediate success with the infantile “L’Ecole est finie” (School’s out). Even the raw energy associated with rock and roll was generally eliminated. The rise of new stars like Frank Alamo (Jean-Francois Grandin, named from a film, Fort Alamo, starring John Wayne) indicated that the fashion was for clean, antiseptic popular singers acceptable to parents and teenagers alike. Alamo’s hit “Ma Biche” (cover of “Sweets for my Sweet”) was a gigantic success in spite of (or because of) its insipidity.

The most successful performer in the new mold was Claude Francois, whose first hit (“Belles, Belles, Belles”) came in late 1962.He was the penultimate yé yé idol, capable of covering American hits in a variety of styles, untainted by the “bad boy” image of the early rockers, and intensely ambitious and hard working. The fact that Claude Francois did not change his name to something sounding Anglo-Saxon indicated a modification of corporate strategy.

This change in the orientation of French popular music (rock and roll) once again coincided with changes in the United States and Great Britain, producing contradictory influences. In the United States, the reassertion of corporate control over the popular music industry was fairly complete by 1958. The resulting “normalization” of the music, plus the aging of the postwar youth cohort and the impact of historically specific events such as the Civil Rights Movement, contributed to the development of commercialized “folk” music from 1960, closely followed by the success of the “Motown sound.” In France, Françoise Hardy, a young student at the Sorbonne, first expressed the new trend by combining the yé yé sensibility with a new intimacy that was far more profound.

With her long, straight hair and the moody lyrics of her own compositions, Françoise Hardy anticipated in France the important transition from the relative lack of social consciousness and the materialist superficiality of the 1950s to the romantic idealism of the 1960s popularized in the United States by Joan Baez, Peter, Paul and Mary, Bob Dylan and others.

At a time when Sylvie Vartan and Sheila dominated the yé yé scene, with their bouffant hairdos and little-girl acts, Francoise Hardy successfullv pioneered a synthesis of the new youth sensibility with the intimate tradition of the chanson réaliste. Her first hit, “ Tous Les Garçons et les Filles” (All the girls and boys), is a rock and roll ballad built upon the most classic chord progression (the C, A minor, F, G used, for example, in Ritchie Valens’ “Donna”). It established the pattern for her future work, a combination of tasteful instrumentation and her own bittersweet lyrics that re-introduced the poetic tradition into the “pop” mainstream of French popular music.

This trend was quickly supplemented with another, even more powerful influence – the British rhythm and blues explosion of the early 1960s. At the very moment that the French groups were fragmenting in order to make way for the new star system of the yé yé era, British groups began to dominate the worldwide commercialization of African-American inspired music.

In France, as always, British, American and African-American influences tended to fuse pell-mell when adapted to French sensibilities and marketing imperatives. The folk singers of the early 1960s, the fusion of rock and roll and music hall created by British groups like the Beatles and the Kinks, and the rhythm and blues revival brought to mass popularity by others like the Rolling Stones, the Animals, and Them, combined to produce a new generation of French performers who resisted the outright corporate control of the music industry, and who insisted on saying something of substance.

Most important are Antoine Murraccioli (who, in a long show-business tradition in France, went by his first name – “Antoine”), Jacques Dutronc, and Michel Polnareff. Although other performers (such as Ronnie Bird and Herbert Leonard) achieved a new level of competence in rhythm and blues singing, the former were distinguished by their assimilation of the new rhythm and intonation and, especially, by the fact that they performed their own compositions.

It was perhaps inevitable that a new type of commercial music in France eventually came to be influenced by the same intellectual criticism that distinguished the new chanson réaliste following the Second World War. The intervening years, those between 1945 and 1962, had involved the French population in bloody colonial wars in Indo-China and Algeria that dominated political debate and conditioned the thinking of youth. The cultural phenomenon of rock and roll, in spite of the crassness of its promoters, could not help being associated with the atmosphere of tension and conflict created by these events.

__________________________________________________________________________

Since the late 1950s, French popular music has been transformed largely because of the assimilation of foreign sounds and rhythms. The greatest impact in this regard was made by the advent of rock and roll and, although the French were far less responsive to it than the British, its acceptance combined with a rapidly changing economy and society to help modify existing musical culture. There was, indeed, a great difference between the inception of rock and roll in France and Britain. Whereas in Britain rock and roll quickly became the property of youth, in France it was used to exploit them

The French only gradually assimilated the new music to the extent that it became part of their cultural expression. This was because, as we have seen, the arrival of rock and roll in France was carefully managed by the French music industry. Control over the means of popular musical production was maintained through a policy of limiting the distribution of foreign records and systematically covering the American hits with French-language versions executed by performers directed closely by promoters. The political and social conjuncture contributed to this control. The beginning of the Fifth French Republic under the leadership of General Charles DeGaulle in May 1958 bolstered a certain nationalist conception of moral order that opposed the liberation of youthful energies that rock and roll represented, and that supported the relative exclusion of foreign products in accordance with the desires of the French record industry.

However, the acceptance of rock and roll by the French public was a complex phenomenon that cannot he reduced to the manipulations of commercial or political interests. How rock and roll was perceived was related to conditions existing in postwar French society transcending the control of powerful interests. For example, a subtle relationship existed between the beginnings of rock and roll in France and the war in Algeria beginning in 1954. The postwar generation of French youth was, in fact, a generation raised in the knowledge of continued war in colonial regions. Attempts to repress struggles for national liberation in Indo-China and Algeria weighed heavily on the consciousness and perceptions of young people, particularly at a time when the labor movement and left political organizations were relatively strong. These wars were as unpopular with French youth as the war in Vietnam would be later with American youth.

For the French, the introduction of rock and roll meant many things. First, it was an obvious manifestation of American cultural imperialism and could he seen as buttressing the western way of life associated with French control over Algeria, where the new music was as popular among the colonial class as it was in France itself. Secondly, rock and roll responded to the frustrations of a youth group unable to express its collective interests in a more coherent way. Dissatisfactions with all political organizations, whether on the Right or on the Left, were confusedly felt, and lacked the conscious formulation they increasingly found as the events of Spring 1968 approached.

Although the enthusiasm shown for African-American rhythms is impossible to attribute to any single factor, French youth was receptive to the new music for essentially the same reasons as youth in other western countries. But the way rock and roll was assimilated was conditioned by deep-rooted cultural sensibilities, established patterns of social interaction, and a highly specific political context.