This is a fairly recent (unauthorised) translation of a book – La Commune de Paris – 1870-1871 – written almost 5 years ago in the wake of the Arab Spring, by some people in Strasbourg (contact: descommunards@yahoo.fr). Although it was translated almost 3 years ago, it appears that there were some minor problems with the translation, which, despite the length of time, appear to have led to the project being abandoned. I say “appear” because despite asking those involved in the translating a few times what was happening with it, they haven’t replied (it’s quite possible that they forgot…I don’t know). But I thought that it was an interesting text, and so – being very impatient – have decided to make it public 2½ years after I was sent it. Nevertheless, I should emphasise that it’s an unauthorised translation and I will take it off the site if those involved in the translation want me to take it off.

The introduction (called “Presentation” here) clearly states its relevance to the present. My main misgiving is that it doesn’t clarify what might be pertinent for future struggles and what is clearly part of a previous epoch, which is the essential way to use history as more than just a simple interesting pastime. There are other bits which I find are a reflection of a kind of leftist type of wooden language – such as the phrase “militant responsibility” ( which implies a responsibility to intervene demanded of the role of revolutionary, when it’s really a question of responsibility to oneself, to one’s own struggle for liberation as part of the general struggle), but this is mainly a question of phraseology rather than the meaning behind the words.

For those interested in a text on the Paris Commune written by a participant, see Lissagaray’s “History of the Paris Commune of 1871″.

Table of Contents

Presentation

Introduction

1.1The historical and international context

1.2 Terminological preliminaries : what is the Commune?

The Revolution is marching on

2.1 Up until September 4th 1870

2.2 September 4th 1870

2.3 From September 4th to October 31st 1870

2.4 From October 31st 1870 to January 22nd 1871

2.5 From January 22nd to March 18th 1871

Victory and defeat of the insurrectionary movement

3.1 March 18th 1871

3.2 March 19th to 26th

3.3 The government of the Commune at work

3.4 April 3rd 1871

3.5 Bourgeois war or class war!

3.6 The Commune government’s decrees

3.7 The public safety committees

Defeat

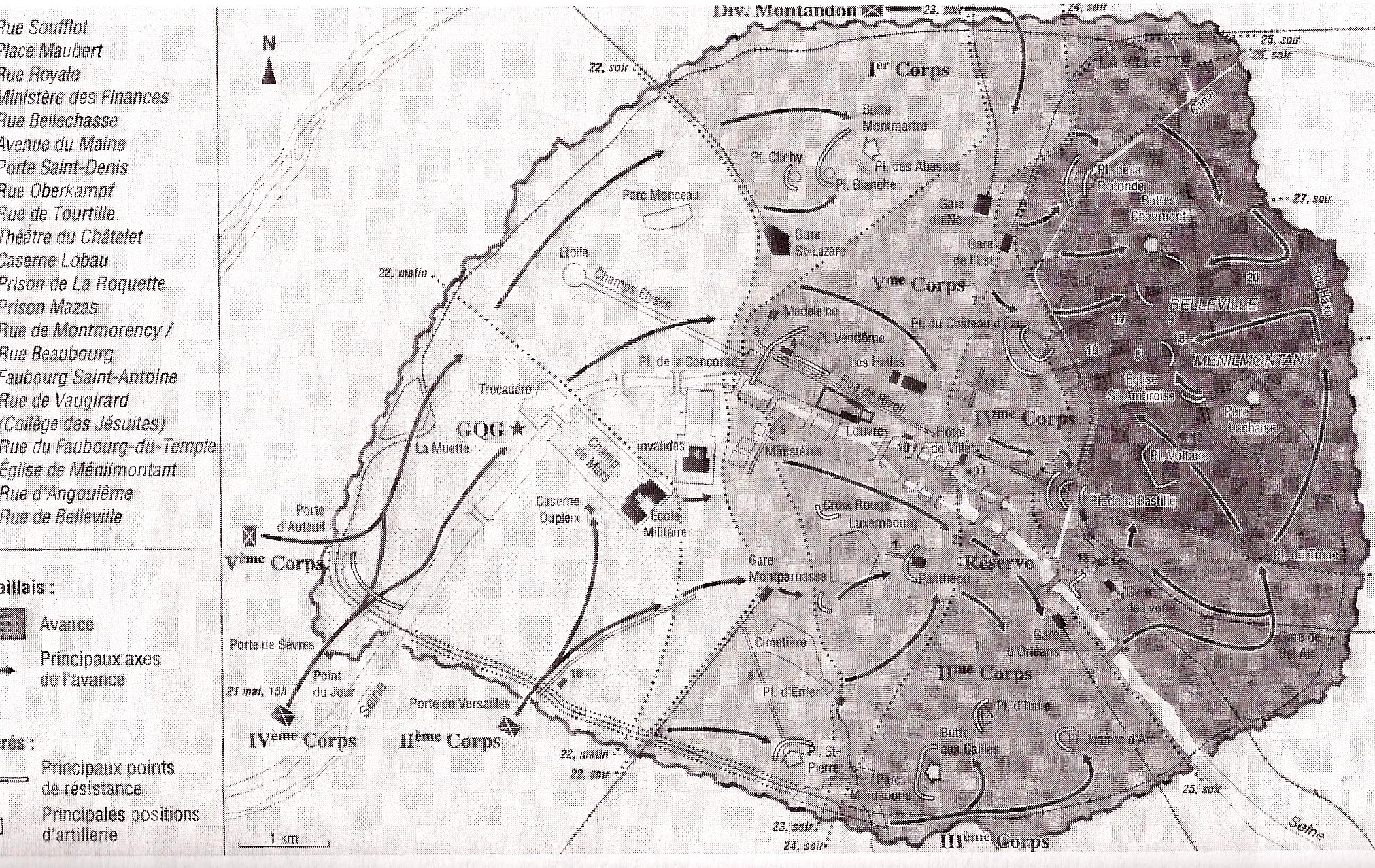

4.1 La semaine sanglante

4.2 Another aspect of the counter-revolution

Conclusion

5.1 Elements of conclusion

5.2 Notes on the IWA, the Blanquists, and other militants

Addenda

Appendixes

6.1 Text signed an old hébertiste

6.2 An article from Le Révolté on March 18th 1882

6.3 Elisée Reclus’s testimony

Presentation

Why write a book about the Paris Commune?

This episode of our history was a qualitative leap in the affirmation of the human community against the terror imposed by capitalism.

It was a proletarian insurrection, a moment of rupture with the status quo established by capitalist domination, an end to the war which the bourgeoisie wages against the proletariat.

It was one of those moments during which the exploited class rises up out of the shadows to express its revolutionary vitality, its capacity to shake the foundations of this world which imprisons it, and so breaks the logic of commodity accumulation, profit-making and the increase in value of capital.

At such moments things fall apart – the vice which holds us to the workbench, the barracks which march us off to war, the wages which chain us to poverty, the property which prevents us from having the means of living, capital which destroys us all the more deeply.

Association imposes itself against the competition and separation which capital maintains in order to ensure its domination. Proletarians spill out of every work place, every army base. They meet, talk about how to organize the struggle, how to throw off the yoke of wage labor, how to impose their needs and organize insurrection.

The bourgeois world begins to sway, the very world which was built on wars for spoils, taking over the whole of the world’s riches, general expropriation, exclusion, enslavement, wage labor. The bourgeois, fat with gold and quite sure of themselves, become pale with fear. Their dominant class position is threatened!

Different struggles in the world today pose through their acts the necessity of a qualitative leap in the confrontation against capitalist domination. These movements which are expressing themselves in Algeria, Iraq, Tunisia, Libya, Egypt, Bahrain and Jordan are powerful movements even if there is the danger of contenting oneself with one more political reform, one more change of head of State…which would only perpetuate capitalist domination and worsen the situation of war and misery. In order to face that danger it is necessary to understand these movements as expressions of a movement of abolition, and not reform, of the existing order. Not understanding them as Egyptian, Tunisian or Libyan movements…but as movements of a class which is one and the same, seeking on a worldwide level to destroy the State which has imposed centuries of capital’s dictatorship on the whole of the planet.

This is not a “spontaneous” explosion, contrary to what the media say, in that this movement is not without a past, without a previous history or in no way prepared or organized. Let’s go back a bit:

-

Revolts in the Gafsa mining area in Tunisia in 2008

-

Numerous strikes, notably in the textile industry, in Egypt in 2010

-

Waves of riots in Algeria in 1988, in 2001, and on a regular basis up until today

All of this shows that what’s going on in this region of the world is the fruit of numerous outbreaks of struggle going forwards at times, backwards at other times, and starting all over again at yet other times. And as we are writing other confrontations are still going on.

By the way, this last decade has been marked by other important struggles: Argentina (2001), Algeria (2001), Bolivia (2003), Oaxaca (2006), Bangladesh (2006-10), Greece (2008), Guadalupe (2009), Thailand (2010),…China, Peru, Ecuador,…as well as the “hunger riots” in over thirty countries in the beginning of 2008.

What these movements have in common is that they all followed a number of confrontations which allowed proletarians to revive the tradition of struggle: reestablishing links of mutual aid, rebuilding solidarity networks, setting up places for discussion, redefining the means and the ends of the struggle…recalling the experiences of the past, deciding on the lessons we can draw from such experiences. These are all factors in a process of maturation and consolidation.

One more confrontation with the uncompromising nature of the State, one more rise in prices, one more set of wage restrictions, one more comrade cut down by bullets or by torture was enough…for revolt to explode, even stronger and more determined than before thanks to this redevelopment of proletarian association and organization.

The social explosions of the 1980s and the early 1990s were sporadic, disappearing just as suddenly as they emerged. It seems that today’s social explosions last and leave behind traces in the form of discussion networks, the writing and circulating of balance sheets of struggles, the will to no longer be beaten down, and the will to looks at things in the long run.

This abundance of struggle leads to passionate and impassioned discussions among revolutionary militants as they are touched by these struggles of which they are themselves a part and an expression. What development is to be given to struggles? Is insurrection a necessary step? Can the proletariat do without insurrection? These questions and the debates which they lead to are the expression of multiple struggles which, starting with human needs, inevitably clash with the State. But the fact that insurrection does not always appear to be the obvious solution is also the expression of a breakdown which has taken place between current experiences and those of the past (such as the Paris Commune in Paris 1870-71). The trace and memory of these struggles has generally been lost.

The central question is: How can we organize against the State so that the permanent war of the bourgeoisie against the proletariat may at last be over and done with? This question is not a new one. Every important struggle has been confronted by it. Generations of proletarians who lived these confrontations and who were involved in efforts to make these insurrectionary movements take a qualitative leap – they left us precious lessons which it is important to re-appropriate. The strength of bourgeois domination is based on ignorance. The discontinuity in the transmission of the memory of past struggles is a gap which social-democratic forces rush into in order to better destroy our struggles. It’s a question of our responsibility. This is not an intellectual debate. It is a question which is posed concretely in struggle. We have to talk about this responsibility.

Some people refuse this responsibility. They praise a sort of pure “spontaneity” of the proletariat which militants, by their presence and activities, would corrupt and deviate from its objectives! The starting point of this attitude is feeling exterior to the struggle, the fact that one does not feel involved, that one does not live it as an expression of a movement. More fundamentally it is democratic poison which, in the name of egalitarianism and anti-authoritarianism, condemns all those who dare to take the initiative to do things, moved by a greater clarity, fed with lessons of past struggles…It especially condemns those who associate so as to make all of these elements into a strength with which to contribute to qualitative leaps in the development of a struggle. It’s time to break with these separations. Today, recognising oneself in the totality of the proletariat’s expressions is crucial. The divisions among our ranks make up the trump card for bourgeois domination. It’s time to go beyond all of these antithetical attitudes, this exteriority, and to take up again with the need for organization, militant responsibility. Let’s develop our criticism of this world and assume this criticism consciously and willingly so that the blows against the abolition of capitalist order may be ever more decisive and powerful.

A lot of historians have claimed that the March 18th 1871 insurrection in Paris was “spontaneous” as if it had not been the fruit of a process of maturing. Nothing could be further from the truth. There were riots in May and June 1869 as well as in May 1870. There was an attempt at insurrection in February 1870. From August 1870 until March 1871 there were several insurrectionary attacks, vast movements in which numerous proletarians – men, women, children – marched through the streets, opposed soldiers, and built barricades. Among them, were revolutionaries who had drawn lessons from the experiences of the past – 1793, 1830, 1848 – organized themselves in the aim of insurrection. We will see that they quickly set themselves to work to give a qualitative leap to this magnificent outburst. When we take a closer look we can see there was no separation between these different actors in the movement. The following text aspires to be a practical demonstration of this assertion.

Certain revolutionaries acted with intelligence, clarity, and authority. They perceived that imposing the Commune was a necessity for resolving the serious problems posed by misery1 and the continuation of a war of extermination. But this was not always the case. At some points solid militants showed themselves to be inconsequential, having an uncritical spirit, and an unconscious complicity with nationalist, communal-ist (Proudhon-ist), politicizing or other ideologies. This is tragic in that at decisive moments, the balance of forces on the point of changing, such inconsequential behavior would allow the State to take back all initiative for years to come.

During the Paris Commune just like today in the movements of struggle in Tunisia, Egypt, Libya,…the State proposes a switch to something more modern, more republican, more multiparty,… Emphasis is put on the departure of the bourgeois faction that was at the head of State, which is judged as being the one and only entity responsible for misery and repression.

“Wherever there exist political parties each of them sees the cause of all evil in the fact that it is his adversary who is at the helm of the State and not himself. Even radical and revolutionary politicians seek the cause of evil not in the nature of the State but in a specific form of the State which they wish to replace by another specific form of the State.”2

So long as the proletariat gives some amount of credit to these forms of replacement it will remain an object of the dictatorship of profit. A form of domination changes and it’s the opportunity for the bourgeoisie to modernize the exploitation of labor power. If the proletariat accepts this change of form, the bourgeoisie is assured of social peace… up until the next outburst .

But what these movements have in common is that they have targeted a series of State institutions -police headquarters, courthouses, parliament buildings, party headquarters, voting centers, prisons, banks, department stores, luxury businesses,…- they express an implicit rejection of the totality of the capitalist system.

“Que se vayan todos” (“may they all go”) was the rallying cry heard throughout Argentina in November 2001. It expressed the feeling of being fed up with the slogans promoting switches in governments. The space the bourgeoisie has to maneuver in is smaller and smaller. Once they’re at the head of State they burn themselves out all the more quickly, leaving the world State of capital with a bottomless pit: no new spare solution will work. It is in these particular moments that we should be worthy of the challenge set to the world of money and property: contributing to its definitive destruction and to the elaboration of a world without State, without capital, without class, without exploitation.

Some Communards, March 18th 2011. Translated version: May 2013.

descommunards@yahoo.fr

REVOLUTION AND COUNTER-REVOLUTION IN PARIS IN 1870-1871

1. Introduction

In France, during the period of 1870-71, the proletariat was storming heaven. This struggle, which is better known as the Paris Commune, has become a historical and worldwide reference. It is a guiding light for proletarians, wherever they may be, in their struggle against capitalist exploitation, private property, the State. It is a point of reference in the night which reminds the proletariat of the path of its struggle and of the strength that it contains, the ability to overthrow existing order.

This movement principally affirmed itself in Paris with the March 18th 1871 insurrection, imposing a balance of forces which compelled the bourgeoisie to step back and to give up territory. It quickly became the epicenter of a shock wave which would be felt all over the world. On May 29th 1872 Johann Most wrote:

“On one side we could see the proletarians of every country, full of great hopes and easy confidence, with their heads turned to the men of the Commune, men they rightfully considered to be their vanguard in the present social war. On the other side were the factory vampires, the stock market knights, and all of the other parasites who, full of fear, shrunk their heads into their shoulders.”

This insurrectional movement became a fundamental reference. Millions of proletarians recognized themselves in the revolutionary aspirations at the heart of this magnificent movement which called bourgeois society into question. Despite the ferocious repression which punished the movement at its shortcomings the Commune left behind words, written in blood: Revolution is possible. A world without class, without State, without private property, without money, without labor can become a reality. The proletariat found hope and courage.

The analysis of such a movement is vital due to its historical and international repercussions. It is necessary to understand its strengths and its errors so that future struggles will not be broken by the same pitfalls. The lessons the proletariat draws from the past can only reinforce it. Our viewpoint is not backward looking. We find our identity in the past, our fundamental determinations, as an exploited and revolutionary class. It is there that we seek the strength necessary to take up the struggle again, just as the tree plunges its roots into the soil so as to take the resources necessary to give it robustness and vitality.

Of course, this magnificent struggle was also the object of distortion, falsification and many facts were covered up. It became the object of a myth and it is high time to criticize this myth. This myth was built by social-democracy. It exploited the feelings of defeat and proletarian anger provoked by the tens of thousands killed, imprisoned, and exiled. It sought to show that the only possible means of changing the world were through pacifism, electoralism, and parliamentarianism. It distorted the profound meaning of the movement which had affirmed itself as a death sentence to the capitalist system and not simply its reform. It proclaimed that this was the very force of the movement and that all other struggles had to follow in the same well-worn tracks. However it proclaimed that all of the movement’s force such as its ability to organize the insurrection was precisely where lay the error not to be repeated. It affirmed that this is what had led to defeat and repression. Of course, what it names defeat is our defeat. Whereas our victory means the defeat of social-democracy.

Numerous attempts have been made to distort the history of the struggle led by the proletariat in France in 1870-71. Against such attempts what matters to us is to take up the path of class confrontation, to analyse the solid backbones and to grasp the limits. It is important for us to go back to this important and generous movement which contained the grain of the destruction of the bourgeois system and the affirmation of the need for communism. This permits us to better distinguish which of the forces present were on the side of revolution and which were on the side of counter-revolution, in whom do we recognize ourselves, and in whom do we definitively see enemies.

1.1The historical and international context

To understand the deep content of the insurrectional movement in France, it is necessary to view it in its historical and international context. This movement was part of a long continuity of different insurrectional movements which came before it and which influenced it.

From 1773 to 1802 there was a period of intense struggles in different parts of the world. What first comes to mind when we refer to this period are the mighty struggles which shook France during the French Revolution. Generally the emphasis put on this particular historical event covers up a number of important revolts which took place at the end of the 18th century. There were notably those which took place in France from 1792 to 1797 among which was the so-called “Egalité” attempt at insurrection organized by Babeuf and his comrades.

Let’s have a look at a very brief chronology of a long list of struggles.

In 1773 formidable struggles known as Pougatchevina took place in Russia. In the British colonies of America an outburst of struggles rose up against both the English colonial presence as well as the bourgeois demanding independence. In 1775 the guerre des Farines took place in France. From 1781 to 1787 there were revolts in the United Provinces. There were revolts against the Spanish Empire. In 1797 slave revolts in Santo Domingo (which would later become Haiti) took place, lasting several years. In 1798 revolts in Ireland left 30,000 insurgents dead.

What we perceive as essential is the interaction of these different struggles. Major events such as the French Revolution were made possible by a conjunction of a whole sum of revolts which took place in France as well as in different parts of the world. The presence of exiled proletarians and the major influence of the Atlantic proletariat, made up of sailors of different nationalities and having an internationalist approach to struggles is of great importance. Importance that we are now beginning to grasp3.

There was a revival of insurrectionary movements in the beginning of 1830 in France, as well as in Belgium, Poland, and Russia.

From 1848 to 1851 a whole series of important uprisings blazed a path throughout Europe such as in February and June 1848, in Germany in 1848-49, in Italy…

Despite the ferocious repression, proletarians kept workers’ memory alive throughout these years in both written and oral form. We have no other explanation for the strength of the workers’ movements at the end of the 1860s which in France reached its peak in the insurrectionary development in 1870-71. The proletariat had the capacity to nurse itself on the struggles of the past, on the balance sheet of their strengths and weaknesses and so strengthened those to come. Those who had once known defeat passed on the experiences of struggle, the lessons to be learned. Different generations did not ignore one another. For example, just think of the “elders” of 1848 who mixed with young revolutionaries at the 1871 barricades! There were many informal meetings taking place in bars, at work, at the places where proletarians would gather, such as the Place de la Grève, in certain neighborhoods…as well as in more structured meetings (mutual aid and resistance associations, secret societies, book clubs, etc.). The need for association, for solidarity, remained alive. It was hidden from the eyes of the State, though it did sometimes rise up at street corners under the steadily rising pressure of the inevitable confrontation to come. Buonarroti, Blanqui and Marx are the most well-known militants of this red thread spanning through the century. But let’s not forget other less well-known militants such as Weitling, Flora Tristan, Bronterre O’Brien…as well as those who shall forever remain unknown, who gave all of their strength to keep proletarian associationism alive and solid.

After the dark period of counter-revolution which fell upon insurgent Europe (1848-1851) there was not another revival of struggles on the scale of the continent until the beginning of the 1860s:

-

In Germany there were numerous struggles, particularly in the mines in Silesia. Many anti-war demonstrations took place all over the country during the Franco-Prussian War and later in solidarity with the Commune. Social agitation remained significant until 1872.

-

In Belgium numerous strikes broke out in the Borinage mines and in the steel industry in 1867.

-

In Switzerland there were strikes among construction workers in 1868-69.

-

In Great Britain, in Austro-Hungary, in Ireland, in the United States…proletarians entered the struggle.

In the same period, both in the decade preceding the Commune as well in the following one important movements were taking place:

-

In China the so called Taïping struggle lasted from 1851 to 1864. Its repression left tens of millions dead. “It is perhaps the biggest peasant war of the modern world, if not of all time.”

-

In Mexico one of the most important insurrectionary movements which the American continent would know was taking place. It lasted two years. The high point of the first seven months of struggle in 1869 was the del Chaco insurrection in the state of Mexico. The bourgeoisie was unable to put out the flames of this revolutionary fire for a long time.

-

In Crete a social struggle movement was beginning in 1866.

-

In Japan “peasant rebellion movements were numerous between 1868 and 1877. Certain historians of Japan claim there were as many as 190, whereas during a period of two and a half centuries there had only been 600 in all“.

-

In the United States insurrectionary strikes erupted in the main cities in 1877.

-

In Bosnia-Herzogovina and throughout the Balkans there was an uninterrupted series of proletarian uprisings against exploiters of various nationalities between 1875 and 1878.

-

In Spain uprisings, strikes and insurrections took place throughtout 1873. The great insurrection of Carthagene started on July 12th and went on until its final defeat on January 13th 1874. Some of those who took part in the Commune lived in exile in Spain and took part in this nearly forgotten insurrection.

We are not trying to establish a definitive list of all of the riots, barricades, insurrections, organizations…especially because following a movement’s traces and bringing forth its class dimension implies a very difficult task of research in that these traces have often been erased. Such a task would be a real battle against the systematic brainwashing that is organized to destroy any memory of struggle.

What we are interested in is the quality, the strength of these movements. The way they confronted the bourgeois world that was trying to impose its need, ever higher degrees of exploitation, reinforcing the State as a means of carrying out control, repression and the destruction of any remaining community of proletarian resistance, of struggle.

Although these struggles remained scattered and lacked both clarity and a determined will to break with their isolation they were all nonetheless opposing the same enemy, capital. They affirmed de facto the human need to do away with money, labor, and war. They affirmed their common essence. They were diverse expressions of the same worldwide being, the proletariat. How then, despite the clear existence of this common being, can we explain the isolation, the lack of affirmation of those struggles4? This question is all the more crucial in that it is still a topical question this seems perfectly ok. Still today the big problem in the proletariat’s struggle is isolation, the difficulty in recognizing oneself in struggles going on in other parts of the world, the difficulty in breaking with and going beyond language barriers, distances, particular histories and identities.

It’s of no surprise that the bourgeoisie’s interest is to present all of these struggles as just a bunch of different cases, born out of multiple causes, with no common essence. Thus the bourgeoisie speaks of “student” and “worker” struggles in Russia while they are “cantonal” in Spain, “farmer” in Italy and “national” in Ireland. For the bourgeoisie it is above all imperative to present all of these struggles within the non-classist framework of the nation and of national defense. Most of these struggles, including the Paris Commune, have been analyzed by bourgeois historiography as “national liberation” struggles. Obviously it is in the bourgeoisie’s interest to hide the elements in these movements which express the community of proletarian struggle wherever they may spring up against the class of exploiters whether they’re French or German, Russian or Chinese, Mexican or…Instead, the bourgeoisie affirms only the existence of a national moment of mobilization, regardless of class, against an “invading” enemy. The bourgeoisie tries to transform a “class against class” war into a bourgeois war. In the name of patriotism, in the name of liberating a territory the bourgeoisie puts an end to the birth of revolution and leads the proletariat to lose itself in a struggle which is no longer its own. In opposition to the bourgeoisie’s work of destruction we are going to emphasize the fundamentally internationalist character of the struggle which was led principally by the proletariat in Paris in 1871 despite its trouble in overcoming the domination of a nationalist framework.

Despite the intrinsic internationalism expressed by all of these struggles it isn’t easy for us to see what links were built between these different hotbeds of unrest, between different revolutionary militants on an international level during the 1860-70 period. It’s obvious that there was no direct interaction between the Taïping struggles and those going on in Europe. This was not the case for the French Revolution as we remarked above. However we can say that such interaction appeared quite natural in other cases and that there were some attempts to make a qualitative leap, as these struggles were all taking place at the same time, in affirming the need to coordinate and clarify objectives.

The foundation of the International Workingmen’s Club (IWA) in 1864 represented an important step in the organization of the world’s proletariat. It came out of the same line as its forbears, the Communist League, created in 1847, and the International Association (1855-1859). The IWA’s coming together was a response to this new wave of struggles. This was of great historical importance. Indeed, this was a meeting place for militants from many different backgrounds. The struggles in many different countries could be centralized there. Many rich debates and arguments took place there which resulted in an ever clearer affirmation of the program for the emancipation of humankind. This would then in turn give greater force to the ongoing struggles. In this way we can say that the struggle in one particular place was lived as a part of a whole, of this international “army” of the proletariat struggling openly against the bourgeoisie.

The example of a little known uprising can only buttress our affirmation. Who knew that there were links between the IWA, based at the time in Europe, and proletarians on the Caribbean island of Martinique? Who knew it had been so since 1865? Who knew that as soon as the September 4th 1870 proclamation of the republic was known, on September 22nd, an insurrection broke out in the south of the island? As soon as the news got around work ceased. Some plantation owners threatened to put down the strike by force. This galvanized the strikers into a forceful reaction of hatred against them. That’s how this general revolt began. Proletarians thought the time had come to radically call into question the social relationship with the plantation owners. They set sugar-making factories and administrative headquarters on fire. That’s how forty plantations went up in smoke in three nights. But the movement was soon crushed. These proletarians naively believed that the advent of the new form of State in Europe would support them in their struggle against their exploiters. They had not organized themselves for a long term struggle. This made repression harder to resist. At least a hundred insurgents were murdered. Insurrectionary movements began a few months later on March 15th 1871 in Kabylia in Algeria and later spread to the whole country. As is the case for Martinique we know very little about this struggle. The French army viciously put it down. There is a bloody irony in this case as the same troops used to put down the proletarians in Paris were duly used to put down the insurrection in Algeria.

We present our analysis of the movement of struggle in 1870-71 as it developed from period to period. This allows us to follow the evolution of the struggle between the classes in its principal phases. But first we are going to try to clarify what we mean by the Commune, to explain precisely what this name really refers to and implies.

1.2 Terminological preliminaries : what is the Commune?

In Paris, all of the rebellions and struggles against the State led by generations of proletarians throughout the centuries, such as Etienne Marcel’s rebellion in 1356, were concentrated in the term Commune. In every time of crisis “the people of Paris called out: Commune“. This word came back in use during the inusurrectional Commune of August 10th 1792 which, after affirming itself for several months, was forbidden by the Convention but expanded until it was eliminated (Thermidor 9th ). This word sprang back after September 4th 1870 and became a rallying cry for proletarians who rose up against the whole of bourgeois forces more and more clearly. On October 8th 1870 the word Commune was openly used during a demonstration against the National Defense government: the proletariat made its demand “Make room for the people, make room for the Commune“. These same terms were used in the red poster which was put up throughout Paris on January 6th 18715.

For us there are different contents which overlap and confront one another in the term Commune: essentially the Commune as the proletariat’s revolutionary uprising, and the Commune as the government of Paris. Bourgeois historiography would not show this distinction because this would imply showing the class confrontation which was taking place. The confusion over these two contents is eminently harmful to the intelligence of the social movement in France in 1870-71. As a starting point for this analysis we would like to make some terminological (political) remarks which may help shed some light on the situation and remove the ambiguity which an undifferentiated reference to the Commune carries:

The newspaper Le Révolté affirmed unambigously that “…the Commune (…) was governmental and bourgeois“:

“How could the masses fight for an order of things which left the people in misery out of respect for bourgeois private property (…) which allowed, at the height of revolution, for there to be bosses and workers in Paris (…)”.

Some years later, in 1898, Elisée Reclus made the distinction between the bourgeois work of the Commune government and what represented the term Commune in the eyes of proletarians:

“The word “Commune” was understood everywhere in the widest of meanings, pertaining to the whole of a new humanity, made up of free and equal comrades who recognize none of the former borders, and live in peaceful mutual assistance all the world over.”

A political balance sheet of the Commune necessarily leads to such explanations in its struggle against official historiography. These academics of bourgeois thought filter events through their own perspective which they describe using their own terminology. Their aim is to protect the organization of the society which they depend upon. When they identify the bourgeois reformist decrees produced by the Commune government with the (confused but real) attacks which the proletariat made against the capitalist State the bourgeoisie is simply projecting today the same political concern which was already a driving force within it in 1871 as it faced armed proletarians: how can it bring the revolutionary movement in Paris back into the framework of a struggle for more republic, more democracy, more State.

That is why in the following text we have used two distinct terms:

-

the Commune which we refer to as such or preceeded by the adjective “revolutionary” when we refer to the revolutionary movement in Paris.

-

the Commune government when we wish to speak about the reorganization of the State in its republican form and in its defense of the pillars of its society – private property, labor, money.

The revolutionary Commune has an undeniable suggestive power for the proletariat. To say the Commune to refer to the proletarian uprising in Paris is like saying the Russian Revolution to talk about the October 1917 insurrection in Petrograd. The proletariat’s strength in its struggle to affirm its needs, its communist project, was so great that it marked future generations with the time and place of their happenings. The Commune, 1917, El Cordobazo, May 1968…are terminological shortcuts which mark the proletariat’s struggle and with which it identitfies.

However when we talk about the Commune government we talk about capitalism’s capacity to break the proletariat’s party6. We refer to the bourgeoisie’s capacity for keeping its State alive. In order to do so it seeks to confiscate the initiatives and directives taken in the struggle by revolutionary workers so as to better destroy them. In distinguishing between the Commune government and the revolutionary movement we wish to point out this bourgeois recuperation, the capitalist State’s great capacity to adapt and co-opt workers’ elements so as to make its decisions seem credible. In doing so it seeks to defuse the revolutionary movement by legalizing it and transforming social attacks into a purely military confrontation – turning the class war, proletariat against bourgeoisie, into a bourgeois war, front against front, Paris against Versailles.

We can refer to one of the essential lessons which Marx drew from this revolutionary period in The Civil War in France:

“I remark (…) that the next revolutionary attempt in France ought not to consist in putting the bureacratic and military machine into other hands, as it has been the case until now, but instead in breaking it.”7

For us, this means that we are not going to try to distinguish between the “good” and the “bad” measures passed by the the Commune government but instead to grasp its essence as an atomizing force against the proletariat’s power, and even more so against the direction which the proletariat was trying to give itself. Just because some militant workers, despite their anterior ruptures, participated in different levels of the Parisian municipal State apparatus (the government, executive commissions,…) that did not give any revolutionary complexion to these structures. On the contrary, it’s an expression of the confusion which reigned among the avant-garde elements, the proletariat’s lack of determination. Mixing up the efforts of participants in the Commune to give themselves a revolutionary direction with the capitalist subject the Commune government never ceased to represent, is an enormous concession to the bourgeois history of the Commune.

The Revolution is marching on

September 4th 1870: The republic has been proclaimed. Patriotic madness is at its highest. The proletariat is drowned in the people.

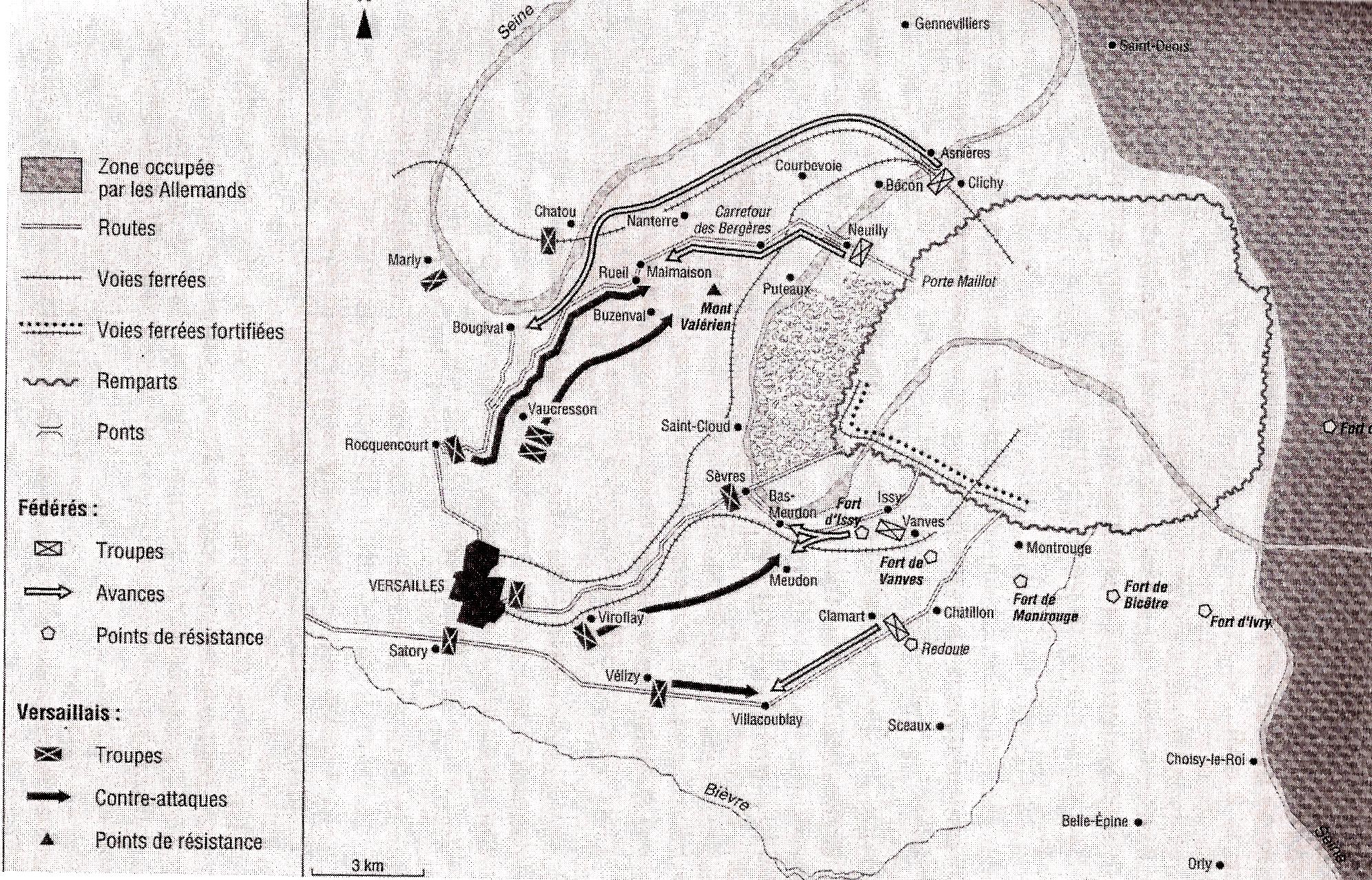

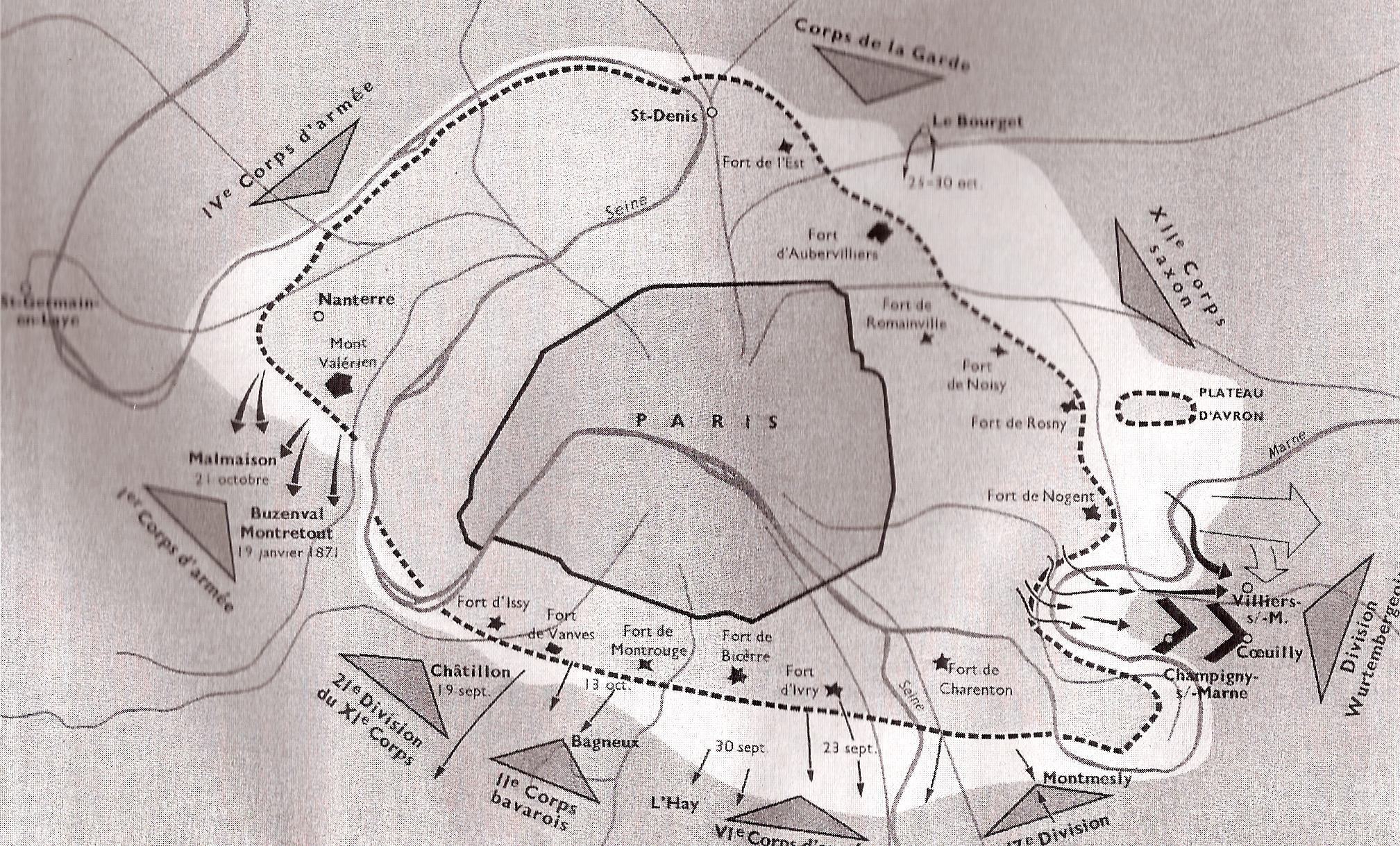

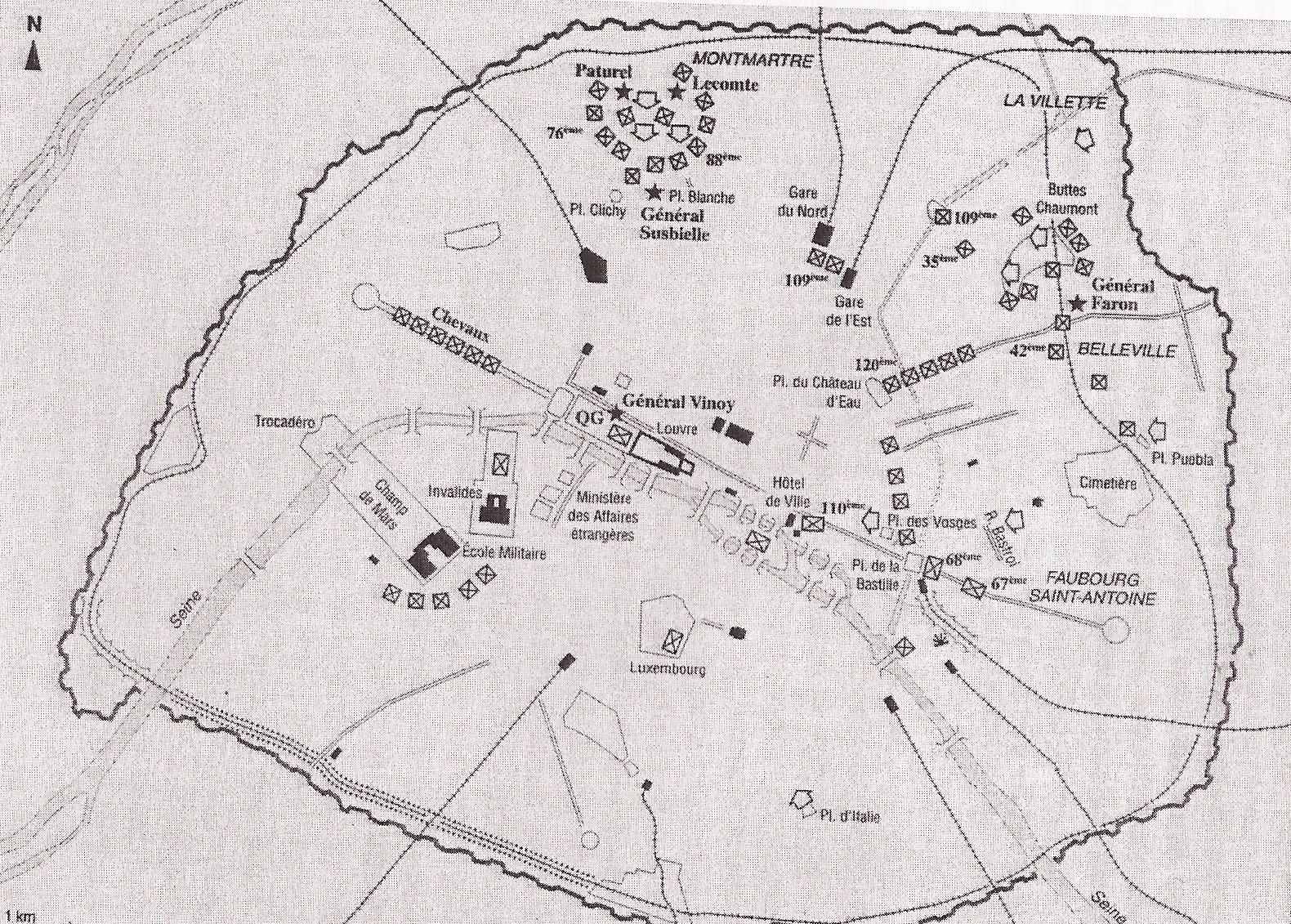

Positions of the German army during the siege of Paris

2.1 Up until September 4th 1870

“In certain periods which usually precede great historical events, humanity’s great triumphs, everything seems to move forward at an accelerated pace, electricity is in the air: the minds, the hearts, the wills, everything seems to be marching forward in unison, in the conquest of new horizons. Then all throughout society an electrical current which unites the most distant individuals in one same feeling and all of the different minds into one thought, which marks everyone with the same will.”8

The strengthening of the proletariat’s power in France at the time of the IWA’s foundation in 1864 and in the following years expressed itself in different ways. Strikes became numerous after 1868 and they were quite radical in the regions around Rouen, Roubaix, Lyons, Clermont-Ferrand, Mulhouse, Paris…1870 was the climax of the struggles of the whole 19th century. Although the bourgeoisie responded to these struggles by sending in the army and causing massacres such as in Ricamarie (10 dead in June 1869) or in Aubin (17 dead in October 1869) we may note that in some industrial centers it was compelled to give in to the struggles’ demands by raising wages and lowering labor time. The proletariat was gaining in both strength and union.

This growing union was expressed in the reinforcement of revolutionary minorities which, from one experience to another, were becoming increasingly radicalized, were breaking away from various aspects of Proudonism9, and were opening up to a wider following. As a result of the organizing efforts undertaken by militants such as Varlin, Bastelica, Aubry, Richard, Malon… and many other militants whose names history does not remember, in the spring of 1870 four big IWA federations – Paris, Rouen, Marseilles, Lyons – were created.

This growing union was an international phenomenon. Proletarians looked to struggles going on in other countries such as England, Switzerland, Italy…They expressed their solidarity by collecting money, and in circulating newspaper articles as a means of propaganda…They recognized these struggles as their own. Going back to César de Paepe “The goal of the International is to bring together into one single group all of the proletariat’s strength.” Proletarian internationalism was tending to become an organized force.

Other poles of proletarian assembly rose up such as the local federations of workers’ union halls or like cooperative restaurants such as those called Marmite which had been set up by Varlin and Nathalie Le Mel. These were real hotbeds of subversion in which revolutionary propaganda circulated. We would also like to add to this list the founding of the Blanquist organization, made up of young militants organized around Auguste Blanqui. They played an important role in the struggles at the time and they would later be found in the forefront in the months to come.

Other indications show that the proletariat tended to become an autonomous force. Public meetings were authorized in Paris as of June 1868. These quickly became revolutionary hot spots. Over a period of two years more that a thousand meetings10 were held. This allowed for debate, the circulation of information and solidarity actions, as well as the preparation of riots and attempts at insurrection such as those of May 12th and 15th 1869, February 7th and 9th 1870 (at Flourens’ initiative) and May 8th and 11th 1870. Social agitation in Paris was growing, especially in certain neighborhoods. The red neighborhoods were Belleville, Montmartre, la Villette, Ménilmontant, imposing the rhythm and the force of the confrontation with the State.

So after all of these years of social peace, riots and barricades were back in the heart of Paris. In these moments there was interaction between the public meetings “where the word revolution was on everybody’s lips” and the street, in which proletarians, sometimes in arms, confronted the cops. The following quote sheds some light on the level of confrontation and the proletariat’s determination:

“At ten o’clock a wave of insurrection spread across the capital: in the eastern neighborhoods a gang armed with iron bars starts the movement. There are attempts at setting up barricades in several different points of Paris. The 20,000 demonstrators along the boulevards turn seditious. The Lefaucheux armoury is attacked. Despite the cavalry’s charges groups of rioters remain resolutely on the offensive. There are many arrests but the people remain in control of the street.”

What was going on is simple. These strikes, associations, riots, amateurish barricades all announced the coming proletarian storm which was going to reign upon the bourgeoisie in the coming months. The Empire was unable to maintain social peace, to placate a proletariat which was gaining in both strength and consciousness.

Declaration of war

The French State declared war on Germany on July 19th 1870. The protagonists gave ridiculous diplomatic reasons which suited themselves fine. This was bourgeois society’s answer to its concern for its own survival, for social peace, for repression against the exploited, putting an end to the proletariat’s power. The State’s interest, in Germany as well as in France, was in the war.

Struggles were also developing in Germany. A movement of strikes, protests and workers’ associationism had been going on since 1868. It especially developed in the spring of 1869. In May 1869 the Reichstag voted for the right to association and the right to strike. It counted on social-democracy in order to hold back this movement. The legal framework, the social-democratic confines and the repression were not enough to prevent strikes, sometimes very tough ones, from exploding such as in the case of the mechanics in Hanover in November 1869 or that of the Waldenburg miners in Silesia during the winter of 1869-70. This is what brings us to the conclusion that the State’s interest was in the war, be it in France or in Germany.

In France there was direct repression as well as various concessions. The IWA was put on trial three times so as to break its organizational structure, its power, and its rising influence. As none of this was enough war became the last resort to wear down this breaking wave. National union, the dream of bourgeois concord, could become a reality: enforcing the unity between the active proletariat and the French people around the traditional values of work, family, and country.

We can say that this holy union worked at first because the proletariat was incapable of stopping the deployment of troops and the departure of their class brothers for the battlefield. At the same time this holy union’s drive to celebrate the reunion of the classes and the dissolving of the proletariat into a populist magma was unsuccessful. The proletariat did not let itself get sucked into the quagmire of nationalism and continued to struggle as if nothing special was going on:

“It would seem the imperial war does not bring about any burst of patriotism among workers. No social truce : strikes continued just like before the war. The newspaper “The Rappel” in July and August 1870 continued to give news of coalitions and guild movements. For example in the August 4th issue one can find information about a new strike among painters and plasterers in Saint-Charmond, as well as news about an ongoing strike among metallurgists in Vienne. Stone carvers had created a resistance society. Marseilles typographers had created a mutual benefit society. In Rouen 800 mechanics discussed the project of creating a trade federation and considered “the productive strike to be the means to get to the proletariat’s emancipation.” Everything went on as if the workers did not feel concerned by this war.“

We can see an even more active approach on July 12th in Paris where IWA militants made a call to workers of all countries and organized demonstrations during which “they were roughed up by a furious crowd who booed them.” This same kind of idiot “crowd” would later be organized by the State in 1914 to spark up patriotic madness while the proletariat dragged its feet in answer to the nation’s call. It is a fact that the French bourgeoisie, under the mask of the Empire, tried to force the proletariat to accept its war while…

“The prefects themselves, in their reports to the government full of servile complacency, in July 1870 were obliged to point out that in 71 departments (out of a total of 87) the population was massively against the war.“

We may also note that in July in Germany and Austria IWA militants were imprisoned for having participated in daily demonstrations against the war. This internationalist attitude, despite its pacifist shortcomings, would be upheld throughout the conflict. Here is what Marx wrote on January 16th 1871:

“On a daily basis German workers’ meetings in favor of an honorable peace with France are broken up by the police.”

Just over three weeks after the beginning of the war the proletariat violently demonstrated its refusal of the holy union, in Paris as in the rest of France.

August 6th: The proletariat sacked the Paris stock exchange.

“The stock exchange was sacked by the people gone mad. Emile Ollivier, in his residence at Place Vendôme, had to face hostile crowds.(…) The next day on August 7th an enormous crowd marched on the avenues shouting “Weapons! Dethronement of the emperor! Republic!” The police were unable to break up the crowd. The cavalry charged.“11

August 7th: Massive demonstrations took place as well as confrontations with sergents de ville in Paris as well as in many other cities such as Lyons, Marseilles, Toulouse as well as in several departments such as l’Indre and l’Ariège. The State reacted by proclaiming a state of emergency in Paris as well as in several other departments.

August 9th: Thousands of proletarians invaded the streets and encircled the Palais-Bourbon which held the Assemblé Nationale. The bourgeoisie was getting scared. Every one of its factions united into a single block against this eruption. It was this necessity to maintain order which explained why the left bourgeoisie put off the declaration of the republic despite the pressure to do so coming from the streets. The other reason that the left gave was that they still believed the French army was capable of beating Prussia. They didn’t want “a revolution at the moment” because those who carried it out would be responsible for the army’s defeat. The next day, on August 10th, many contingents of troupes de lignes as well as gendarmes (40,000 soldiers who were normally to leave for the front!) protected the seat of the legislative body while the police proceeded to make numerous arrests.

August 14th: The pressure had reached such a degree that the Blanquists tried to force the hand at la Villette. They tried in vain to lead the suburb inhabitants in a riot. After this failure many of the leaders were imprisoned or else sentenced to death like Eudes and Brideau, who would later be broken out of prison on September 4th. Meanwhile others went into hiding and waited for a more favorable time.

Although these proletarian actions were tainted with patriotic vexation after the French army’s first defeats were announced it is undeniable that the bourgeoisie was getting scared. In addition to the presence of 40,000 soldiers to keep order the bourgeoisie reacted through a great wave of repression and a campaign of terror. These were carried out in the name of the fight against agents provocateurs in the pay of Prussia! Arthur Arnold wrote:

“At gatherings nobody dared speak to those around them. If anybody raised their voice so some manly words could be spoken the citizens around him immediately looked at him mistrustingly, thinking he must be an agent provocateur. Paris saw the police everywhere and this vision, this nightmare, dazed them and made them incapable of any common action.”

The bourgeoisie armed sixty National Guard battalions on August 12th. Its perspective at the time was to “arm the bourgeois, excluding proletarians, especially former soldiers so as to have sufficient strength to oppose the proletariat’s revolts, emboldened by the troops having been sent away (…)“12. So at the start these battalions were composed of “reliable” elements coming from bourgeois neighborhoods.

This National Guard originated in the permanent committee at the Hôtel de Ville which was made up of 48,000 men the day after the Bastille was captured in 1789. The bourgeoisie had organised this committee directly against the proletariat which had started arming itself, attacking prisons, and taking hold of stocks of flour. It wasn’t until ten days after the strafing at the Champs de mars on July 17th 1791 that the National Guard would definitively get its name. Back then, as was later the case in 1848, class struggle was able to separate the members of this bourgeois organization which misery had driven to rise up against the status quo from those who longed to perpetuate it.

On August 8th 1870 the Jura prefect informed the government that “rogue soldiers and national guardsmen want to form army corps. Everywhere people are demanding arms. Emotions are inflamed.” Jules Simon was able to write that “we were especially preoccupied with Paris (…) because the whole of Paris was rising up each day, demanding arms and threatening to seize them if they were not given…” This explains why, not even a month later on September 6th, the bourgeoisie was compelled to arm sixty new “moderate” battalions. Yet all they received were old rifles whereas the regiments which had been recruted in bourgeois neighborhoods had new, high performance Enfeld rifles. Such rifles had already proven to be quite a marvel in the repression of the strike at Ricamarie. A few weeks later two hundred fifty-four National Guard battalions were formed, the majority of which were present in working class neighborhoods. In all, this made for 300,000 National Guardsmen (out of a total population of about two million). The organization and the arming of the National Guard became a danger for the bourgeoisie in that there were now proletarians in arms, stationed in their own neighborhoods. What’s more, these National Guardsmen elected their leaders. These proletarians, despite their uniforms, quickly came to elect those whose anti-governmental practice matched the closest to the rising general feeling of discontent. Besides that, their pay was lousy.

At that point, during the highly charged month of August, every bourgeois faction, republican as well as imperialist, was scared of their historical enemy’s brutal awakening. Bakunin summed up their practice this way:

“It’s better off, they think, to have a dishonored France, lessened, momentarily submitted by the Prussians’ insolent will but with nonetheless the certain hope of rising up again rather than to have a France killed forever, as a State, by the social revolution.”13

If the bourgeoisie was clear about the threat it was facing, the proletariat was not conscious of its revolutionary potential. Its practice, its actions, though they may have contained a threat to the State’s stability, remained bogged down in patriotism. This obscured the perspective for uncompromising struggle against all bourgeois factions. He certainly had his reasons when the scoundrel Jules Favre said that…

“Order could only be guaranteed and the population of Paris could only be tamed by stirring up the patriotic fever running through it.”

This republican faction would know how to play its cards with this enormous weakness so as to nip in the bud any proletarian attempt at affirming itself on class grounds, a break with all of this political scheming! The only perspective which seemed to stand out at the time was that of a war of national defense, that is, in defense of the State.

The IWA, through the voice of its general council, that is, through Marx, placed itself on bourgeois grounds. The first IWA address on July 23rd justified a defensive war on the part of the German bourgeoisie and got mucked up in a lot of trifling considerations about the fact that this was a “dynastic” war opposing “bonapartist” France to the Germany of the “junkers“. This address placed itself on the grounds of the aggressor nation and the attacked nation, which, in the end, causes one to have to choose sides, one State against another State, a choice between one or another bourgeois faction, be it imperialist or republican. While this war, just like all bourgeois wars, is always waged against the proletariat.

The French military defeat can be explained as a result of the army’s complete negligence as opposed to the German army which was toughened after its victory at Sadowa (1866) against the Austro-Hungarian army. The German army was well-equipped, superior in both military force and intelligence. Hated, powerless, and no longer credible the Empire was going to have to make room for another bourgeois faction.

2.2 September 4th 1870

On September 2nd the German army captured a large part of the French army (including Bonaparte) at Sedan. This military defeat, synonymous with thousands of dead and wounded, was going to push the proletariat into action, despite the unending repression14, the tight police control, and the intensification of hardship. It was time to slaughter the dying Empire, hated just as much as its very pillars: exploitation, misery and war! On September 3rd as soon as the defeat was announced the proletariat rose up. Shouting “Dethrone the emperor! Republic!…from Belleville, from Ménilmontant, from Montmartre, workers poured forth in numerous columns.” (Arthur Ranc, Souvenirs, correspondance, 1831 – 1908). But unable to clearly explain their anger or give a direction to their impulse they were easily overtaken by nationalist poison.

Blanquist militants were able to give a direction to the workers’ outburst. This was accomplished more easily in that even before proletarians had taken to the streets these militants had intensified revolutionary propaganda in order to prepare a demonstration on the fourth. Their strength was in their ability to give a framework to all of this energy and to give it a precise objective: the legislative body, the place where parliamentary scoundrels met. At this time they acted more in tune with the proltariat’s energy and the determination of the active proletariat, as opposed to the August 14th failure, and so were naturally brought to the head of the movement. Even if there were IWA militants, such as Chatelain, veteran fighter of 1848, it was Granger, Pilhes, Ranvier, Peyrouton, Trohel, Levraud, Balsenq…Blanquist militants, who stood out, “in all, [they] came out to a few hundred disciplined and determined men, backed up by about two hundred students and workers who were accustomed to act with them, in the latest struggles against the Empire“.

That’s how on September 4th 1870 an insurrectionary movement brought proletarians to the legislative body at the Palais-Bourbon. They invaded the building and dismissed the ministers. They found armed proletarians there in the uniform of the National Guard. They found in them other proletarians, as determined as they were, coming from the outskirts of the city. They also found a number of moderates as well as fans of the republican left who only wished for a personnel change at the head of State. At the time, proletarians were forcing their way through gendarme and army lines, meeting little serious resistance. The Blanquist militants formed two groups. One forced open the doors to the Ste. Pélagie and the Cherche-Midi prisons so as to liberate imprisoned comrades. The other group went to the Palais-Bourbon so as to overthrow the Empire and proclaim the republic. The left members of parliament did not just stay sitting there. If the republic was proclaimed at the Palais-Bourbon they were going to have to share power with the Blanquists. As the proletariat was invading parliament Jules Favre, that republican scumbag, exclaimed:

“I beseech you. Not a day of blood. Don’t force brave French soldiers to turn their guns against you. They only bear arms against foreign lands. Let us all be united in the same thought, the thought of patriotism and of democracy (…) The Republic? We shouldn’t proclaim it here but at l’Hôtel de Ville.“

To remain at the Parliament (l’Assemblée) meant to dangerously link oneself to the memory of May 15th 1848, when, through the voices of Blanqui’s partisans, proletarians clearly affirmed their struggle against the bourgeoisie. Favre, expert in swindling and conniving, knew it was important to designate l’Hôtel de Ville as the best place to proclaim the Republic. Indeed, that is the place where the provisional governments of 1830 and 1848 had been proclaimed. And both had shown they were able to contain the proletariat despite its determination to bring its struggle further ahead.

In the beginning of August 1870, the same republican members of parliament, such as Favre, had run away when proletarians had asked them to overthrow the Empire. This time, they opportunistically played the role of a replacement faction for the bourgeoisie. The Blanquist militants, naive and unaccustomed to such bourgeois manoeuvring, ended up losing the initiative in the movement.

The struggle’s limits

Ever since the French Revolution in 1789 the proletariat’s main weakness has been the ideology of politics. This weakness stems from a stupid admiration for this event. It reduces the force of a proletarian insurrectionary movement which, in its practice, tended to call into question the totality of the bourgeois world. Instead it prefers the taking of political power by its so-called representatives and the carrying out of a whole series of reforms which will in no way touch the basis of capitalist society, quite the contrary: nationalization, development of productive forces , agrarian reform…This ideology rests upon a false understanding of the notion of the State: it is understood as a neutral apparatus which different classes may occupy and use as they see fit. Though the State is nothing other than the dictatorship of Capital organized as a force! The politicist discourse is the following: Workers, you have taken arms so as to topple over the government. Now it’s time to let your representatives manage society in a new way! The proletariat thus lets itself become dispossessed of the means and the goals of the struggle.

That’s how these bourgeois got what they were after: breaking the movement which could have turned violently against them in the Palais-Bourbon. Heading back into the street, on the way to this symbolic place which is l’Hôtel de Ville, all of the revolutionary force and potential was watered down and lost. The Blanquist militants had been tricked. But their weakness is just the expression of a lack of rupture of the proletariat as a whole with this very French Revolution myth. In this way it contribued to channeling and containing the insurrectionary movement within the limits of bourgeois order, while at the same time invigorating one of politicism’s streams of lifeblood which is republicanism.

Republicanism is the belief that the proclamation of the republic guarantees a change towards a better world. Ever since 1789 in France nearly every riot, struggle, insurrection…had been carried out in the name of the republic. On September 4th the proletariat fell into the same republican trap.

Yet Gambetta had precisely defined what this meant when he said:

“Only the republican form allows for a harmonious conciliation between workers’ rightful aspirations and the respect for the sacred right of property.“15

The only problem is that “the respect for the sacred right of property” always means more exploitation through work, more war, more misery. This republican ideal (parliament, elections….) would last throughout the 20th century and keeps on acting today as an ideological, terroristic, paralyzing straightjacket.16

Politicism manifested itself in the insurgents’ tragic indecision as they ended up turning to “people’s representatives” for the pursuit of their action. They distorted the very action which they had undertaken themselves : the sabotage of a session of parliament. In doing so the proletarians remained victims of this representative, electoralist, rule-abiding, parliamentarian fiction. The myth of a fairer representation had struck again. The proletariat would lay its head on the chopping block by being governed by republicans like Troch who at the end of August shouted from the rooftops:

“To avoid a revolution I will do anything I can.“

Militants in the forefront of struggle were themselves caught up in this politicist tendency. They later played the tragic farce of the historical cuckold, laying the victory the proletariat had won in the streets gun in hand at the feet of our enemies!

The proletariat’s lack of rupture with democratism could be found in each of its upsurges up until May 1871.

*****

It’s important to note that at the same time that these events were taking place in Paris the proletariat’s force was expressing itself in other parts of the country (Lyons, Marseilles, Grenoble):

“In the autumn of 1870 there was a first revolutionary wave in which Paris did not play the leading role. The Commune had begun to exist in the country, notably in Marseilles and Lyons, in September. In the Midi and the southwest there had been some progress among leagues which had already united the essential characteristics of what would later be the Paris Commune. If war was the foremost of their preoccupations it was a revolutionary war.”17

What is tragic is that, at that time, no one made any effort whatsoever to coordinate or centralize these revolutionary hotspots. Each remained stuck within its own geographical limits. This in turn reinforced the movement’s limits, especially concerning chauvinism. This was especially the case in Paris. It temporarily caused the insurrectionary movement to suffocate. It turned the movement from its path and falsified its very roots as we shall see in the following chapter.

2.3 From September 4th to October 31st 1870

In this chapter we’ll see how the bourgeoisie took back the initiative. The proclamation of the republic was an end to the proletariat’s insurrectionary dynamic. The contradiction was clear: either the proletariat or the French people. For the proletariat the only solution was revolution, for the French people, it was military victory. Many would die and suffer before a revolutionary pole emerged from the nationalist, populist swamp into which the bourgeoisie was trying to drown us and that pole would be clearer and stronger than the previous one.

The proclamation of the republic brought the movement to a halt which lasted about two months, until hardship and terror pushed the proletariat to partly cast aside its republican illusions. But the initial poison of nationalism which “is undoubtedly the most powerful feeling which capitalism can awaken and turn against revolution“18 persisted until May 1871.

In September and October 1870 the problem for the republic was the following: How to maintain or to reconstitute an army able to shoot at the “reds” and the “riffraff”? Bazaine, the head of the French army, secretly negotiated with Bismarck for the return of the Rhine army which had been encircled at Metz…”so as to have these troops carry out a 180° change in direction, substituting the protection of the social order instead of the defense of the national territory“. The republic‘s left faction, impulsed by Gambetta, was going to organize an “all out war“. They did this out of their aspiration to fight against revolution and at the same time they echoed what was on the lips of many proletarians, prisoners of patriotic, ideological scum.

So the bourgeoisie was able to impose an apparent division on society: on one side were those who wanted a Prussian victory so they could crush the “reds” and on the other side were the “real patriots” who wanted an “all out war” so as to impose a republican regime.

The nationalist trap was not dead, it had in fact been reinvigorated thanks to the new National Defense government. This time though, the government’s title carried the magical word “republican”. Nationalism was also soon to express itself in one of its multiple variations: the “treason” of the National Defense government. We put this “treason” between quotation marks because it was nothing but an expression of loyalty to the bourgeois program of the destruction of the proletariat. It consisted in sending massive numbers of proletarians to the front in such conditions that left no doubt as to their fate: the army’s defeat and massacre. The bourgeoisie made no mistake. At first it sent the most combative workers to the front lines. It had done the same thing in September 1792 to rid Paris of its most revolutionary elements. It cloaked this policy in the struggle against monarchist reaction. It did the same thing later in Spain in 1936, emptying Barcelona of its insurgent proletarians by sending them to the Aragon front. Both the Empire and the Republic showed their true loyalty to the program of counter-revolution, beyond the rivalry between them: have a maximum number of proletarians killed in order to smother the movement of revolt! But the bourgeoisie still stood the chance of losing some feathers in this dangerous “game” which it was obliged to play. The transformation of the proletariat into the French people remained incomplete. The German army, which was also the enemy of the revolution, was more and more often likened to the National Defense government.

After September 4th nationalist madness really took hold of the proletariat: “the fall of the Empire transformed the meaning of the war: yesterday Prussia faced an army; today it faces a people“. This was so strong that different proletarian groups broke with two of the revolution’s fundamentals: class independence and internationalism. These groups found themselves on the same unclassist ground as the bourgeois forces which fought to impose a framework, designating the Germans as the only enemies. The revolutionary movement, spurred on by misery, would be unyielding in its definition of its real enemies – be they republicans or monarchists…be they French or German.

The nationalistic and chauvinistic practice of different proletarian groups and militants

Blanqui had a new newspaper La Patrie en Danger [The nation is in danger] – quite a program in itself! – which appeared between September 7th and December 8th 1870. Through it he contributed to imposing a terrible confusion in the proletariat between social struggle and national struggle (despite the resistance of certain militants):

“There are no more nuances in Paris in the presence of the enemy. The September 4th government represents republican thought and national thought.”

Patriotic fever crushed Blanqui’s class reflexes, dissolving the very socialist perspectives which had once been his and ending up reducing him in the end to the basest racism:

“On this Earth where we debate the question of progress or the failure to act is of dignity or human servility, of the Latin race or the Germanic race.”

Blanqui’s practice and Blanquist militants’ practice undeniably contributed greatly to the proletariat’s confusion and disorientation in September 1870. They saw themselves as following in the steps of the revolutionaries of the previous century whom they unfortunately identitified as the hébertistes19. The Blanquist militants, just like the hébertistes, didn’t understand the counter-revolutionary function of patriotism. One of their limits, and not the least, was in containing the struggle within a national framework. They rarely tried to situate the debate on an international level. The Blanquists’ position can be illustrated in the following La Patrie est en danger quotation from September 1870:

“Don’t forget that tomorrow we will be fighting not for a government, for caste or party ideas, not even for honor, principles or ideas, but instead for the very stuff of life, for the breath of all, for what makes up a human being in its highest form, for our country.”

The IWA, through the Parisian Federal Council’s voice, ended up supporting the National Defense government. The IWA’s French federations asked Gambetta to organize defense. The foreign branches approved. The French federations justified this chauvinism as a necessity for the sake of credibility towards the “people”, a prelude to the populism which would hold sway until May 1871. Here is how they expressed themselves even at this early point in the events in September:

” In the name of justice Republican France invites you [Germany] to take back your armies…By the voice of 38 million beings, animated by the same patriotic and revolutionary feeling…“

It was prinicpally IWA and union hall militants who were behind the creation of twenty Republican vigilance and defense committees. During their first meeting on the evening of September 5th they decided that “these committees would be at the disposal of the provisional governement, to carry out measures for preserving order, and they would devote themselves wholeheartedy to the defense of the capitol“. Despite the protagonists’ good intentions, wanting to make workers’ demands heard, this nationalist practice could only lead to a negation of the proletariat’s struggle against the State. They devoted all of their militant energy entirely to the defense of these committees. This was detrimental to the reorganization of the IWA sections.

For the IWA General Council in London the, critical, support for the republic was obvious: “we salute the advent of the republic in France“. In his second address to the IWA General Council, written between September 6th and 9th, Marx wrote:

“Any attempt at overthrowing the new government when the enemy is knocking at the gates of Paris would be desperate madness. French workers must do their duty as citizens. But at the same time they must not let themselves get carried away by the national memories of the Premier Empire (…) Calmly and resolutely they take advantage of the republican freedom to methodically proceed to their own class organization.”

Auguste Serraillier, sent by the London General Council, declared during the September 16th session of the Vigilance committee:

“It is incredible to think that for six years people could be Internationals, abolish borders, no longer distinguish a foreigner, and then sink to the point where they are just so as to conserve their phony popularity of which sooner or later they will themselves be victims (…) But they know, just as I know, that they are fooling the people by flattering them. They can feel they are digging themselves into a hole. May I say they are afraid to frankly admit they are International. This is unfortunate. So it follows that they can do nothing better than to parody the 1793 revolution.“20

It is tragic to see that all of these militants contributed in breaking the insurrectionary rush of September 3rd, as they were unable to understand its revolutionary force. As we have said earlier, it is important to recall that all of the proletariat’s explosive potential was first of all the expression of its visceral hatred for the bourgeoisie and its war. Nationalist poison came to replace this class reaction and to bring the proletariat to fight side by side with the bourgeoisie. Having gone through this cruel experience the proletariat would later be compelled to break with this situation and to struggle more clearly on its own class grounds. But in order to make this rupture it was going to have to go through the cruel experience of its alliance with the bourgeoisie first.

From October 1870 on the Paris siege brought on a shortage of everything. Proletarians’ living conditions, for which the government expressed nothing but contempt, compelled them to break with national unity. Inside of the Republican Vigilance Committees, which had at first been organized for a better patriotic defense, a class expression was little by little starting to affirm itself. This was principally the case in proletarian neighborhoods such as Belleville, Montmartre, and la Villette which had already had a long tradition of struggle. Although they never made a clear break with nationalism they had come to distance themselves from the Republican Central Committee, which coordinated the Republican Vigilance Committees‘s activities, tied up in the defense of the nation.

On September 5th proletarians came out of their neighborhoods several times to demand the government defend the nation better. Each time they were ignored. On September 15th and October 8th the Republican Vigilance Committees criticized the National Defence government’s indecision through posters. It was during the October 8th demonstration organized by the Republican Central Committee that the Commune was for the first time openly revendicated.

Starting in October the proletariat began to come out of its state of lethargy:

Contradictions were running through it. It was compelled to struggle against everything that bourgeois society had taught it, reproducing this society while at the same time fighting against it. This was the case, as we have seen, for nationalism, politicism, parliamentarianism, bourgeois traps in which the proletariat gets stuck from time to time. But the winter situation with its repression, misery, cold and hunger pushed the proletariat to forge ahead.

The proletariat’s strength could once again be felt through a myridad of organizations and meeting places. The more explosive the situation became the more rapidly events occured. Not only were the Republican Vigilance Committees becoming increasingly radical, but they had also given birth to a whole series of organizations such as the clubs. These tended to break free from any support, even critical support, for the National Defense government.

While the Republican Vigilance Committees are quite well known the existence of proletarian clubs is much less well known. They sprang up as direct descendants of the public meetings which had been authorized since 1868. Proletarians debated about all of the inherent problems in a revolutionary process in such clubs as le Club démocratique des Batignolles, le Club de le Révolution démocratique et sociale, le Club des Montagnards, etc. Speculators, pawnshops, the National Defense government’s lack of reactivity were most notably denounced here. The need for building the Commune was stated many times. These clubs became increasingly radical, parallel to the Republican Vigilance Committees. Many combative proletarians found a place for themselves there. They brought their grievances, their bitterness, their hatred. While governments changed dissent found continuity in the clubs!

Battalions of National Guardsmen left their red neighborhoods several times this month, led by Flourens, Sapia, and Duval to go to l’Hôtel de Ville in order to voice a series of demands. Their demands included a massive sortie against the German army, Enfeld rifles, municipal elections and the requisition and rationing of food. Each time the government, full of haughtiness and contempt, showed the delegations to the door. In such conditions it is of no surprise that the idea of a show of force had developed.

On October 27th the French army surrendered at Metz. Word of the surrender soon spread. The news didn’t reach Paris until the 31st.

On October 31st the show of force became concrete.