Street-sweepers burn their municipal uniforms while ‘arresting’ the mayor and Regional Executive Committee of the South African capital city, Pretoria (Tshwane), who they locked inside the mayoral building

(14th September 2015)

‘Developments in South Africa overwhelm all accounting. That which would cause headlines in most countries is often, in South Africa, so commonplace that it scarcely qualifies as news’

– Chris Shutes, On the poverty of Berkeley life and the marginal stratum of American society in general, 1983

Could Chris Shutes have had any suspicion when he wrote these words, that his statement would remain true over three decades later? Imagine what would happen if the mayors of London, New York, Paris or Moscow were trapped in their offices by street-sweepers, and only escaped under heavy police escort? Yet when this happens in SA today hardly anyone takes the slightest notice!

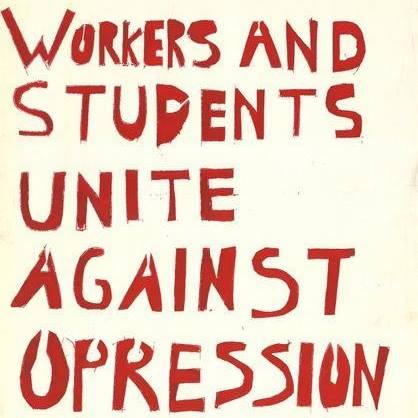

The action of the Gauteng workers (sequestrating Pretoria’s mayor and his executive committee, etc.) is interesting as a rather hilarious example of paternalism gone horribly awry. South Africa thoroughly conforms to the standard pattern of capitalist development in coca-colonial (i.e. neocolonial) Africa whereby the state serves not so much as an ‘instrument of government’ to balance the competing interests of ‘civil society’, but rather as a vehicle of accumulation by which a native bourgeoisie, previously excluded from the commanding heights of the economy, amasses wealth at an accelerated pace, some of which is used to buy-off the co-operation of the working class. Though in the case of South Africa the comprador BBBEEourgeoisie (the billionaire beneficiaries of ‘Broad Based Black Economic Empowerment’ also known, in the words of a new struggle song, as the black boers) came late to the table of political clientelism, the working-class backlash against this established order, which has begun to sweep through the continent literally from Cape Town to Cairo has not been delayed. The workers themselves, far from being gratified by the blatantly corrupt procedure by which they were preferentially given jobs as members of the ruling party (in a country with an unofficial unemployment rate of 40%, work is one of the primary favours dished out by the political classes to placate the masses), straight-away began, almost as soon as they were given their uniforms, to take audacious steps not only to impose their own conditions onto these miserably jobs but also demand the power to recall at will the very politicians whose power is supposed to be guaranteed by this favouritism!

The words of the workers themselves, who two weeks ago attacked six vehicles, burning four to ashes, as well as a municipal building and two water tanks, razing the latter to the ground, as part of the same struggle, and the impotent (ridiculous because blatantly false) response of the authorities, are priceless as a snapshot of the increasingly volatile power-relations in the South African class struggle:

“Vat Alles” worker, Emmanuel Maselane, said their grievances were valid and they no longer recognised what the City of Tshwane had to say about the matter as it was becoming devoid of any relevance. “We want Sputla (Ramokgopa) to step down. He can’t take this city forward. We were hired by the REC because we are members of the ANC and not part of the municipality. The REC, which is meeting here right now, needs to come out and address the issues that we have,” said Maselane. What angered them the most, he said, was that they were not being taken seriously. “They use us for taking part in door-to-door campaigns before elections, which is not stipulated in our contracts. We will join other political parties, because they know what is happening, if this situation is not addressed,” he added. However, ANC Tshwane regional spokesman Teboho Joala denied these claims and said the issues raised by the employees needed to be handled by the municipality as this was not an ANC issue. “Employment cannot be handled by a political party. This is a matter that needs to be addressed by the municipality…”

These lying assurances, met not only with howls of derision but precipitate action on the part of the workers, speak volumes about the erupting contradictions of the present moment. The conflation of the state with the ruling party, and the people with the state, a procedure which has hitherto been exploited with impunity for the benefit of a governing elite, is now turning around to bite these same governors in the arse with the fierce zeal of a starving jackal.

The moment people begin to take the false promises of the political spectacle at face value, the false unity under which real social antagonisms were previously hidden undergoes a reversal of perspective, and the irreconcilable conflict of interest between rulers and ruled is brought to the surface with a vengeance. Now that the cows have come home to roost, this explosive return of the repressed has left the blithe beneficiaries of blatant doublethink out on a limb, up shit creek without a paddle to stand on. The paralysis of the dominant regime, damned if it does and damned if it doesn’t, is illustrated by the ongoing rebellion in Limpopo, where earlier this year residents of Malumalele imposed a decision by the Municipal Demarcation Board to provide them with their own municipality through an extensive two year struggle beginning with a 20 000 person riot and culminating in a massive social strike, only to have this decision provoke another social strike this month by residents of neighbouring Vuyani who now demand the decision, which included them in the new municipality without their consultation, be reversed! Dilemmas such as these, which trouble the political managers of social crisis with increasing vigour as the years go by, bring to mind an apt adage coined by journalist John Reed: ‘In the relations of a weak Government and a rebellious people there comes a time when every act of the authorities exasperates the masses, and every refusal to act excites their contempt.’

This weakness at the theatre of operations level, as they say in military jargon, is mirrored by weakness at the tactical level: ‘On Monday, protesters implemented what they call a “total shutdown” of services, which has led to pupils being barred from going to school and community members not being able to go to work as all taxis and buses are non-operational. Several police vehicles were also damaged, and several nyala’s (armoured vehicles) were also seen parked at the local police station with flat tyres.” The situation here, especially at night is not good, because whenever the police try to disperse the protesters, they run into the bushes, where they set traps by leaving nails on the ground and that’s how some of the police vehicles get flat tyres,” he said. Malatjie said so far, two hardware stores and two taverns were broken into, where alcohol was stolen.’ (Violent Vuwani Remains Tense, The Citizen 2.9.2015) Which goes some way to explain why, in all this burning and looting, only a single person carrying a few bottles of booze was caught.

All of which is being played out within a context pithily summarised by Peter Alexander in Marikana: A View From The Mountain and A Case To Answer, written in 2013, the year after the state felt compelled to massacre striking miners whom it could no longer control through other means:

‘Since 2005, South Africa has probably experienced more strike days per capita than any other country. The two largest were public-sector workers strikes held in 2007 and 2010, with the second of these entailing greater rank-and-file participation than the first. More broadly, the Workers Survey revealed that “around half COSATU members involved in a strike thought that violence was necessary”, with most of the violence, or threats of violence, being directed at scabs. In addition, South Africa’s level of ongoing urban unrest is greater than anywhere else in the world, and there were considerably more community protesters in 2012 than in the previous year. The working class gained confidence from the critical part it played in the overthrow of apartheid, and it has been accumulating grievances without suffering major defeats in the post-apartheid period 1. This is a dangerous moment for the country’s rulers, and it is more difficult to reform the labour relations regime now than it was in 1924, 1979 or 1985. No doubt there will also be some in the cabinet who will recall Alexis de Tocqueville’s aphorism that “the most dangerous moment for a bad government is when it begins to reform.”‘

The fact that actions such as those of the Pretoria street sweepers remain ‘scarcely newsworthy’ seems to me a sign not only of the overwhelming extent of social contestation in this country, but also of the underwhelming effect these struggles have been capable of producing beyond their immediate local situation. The fact of the matter remains that, unless one takes an interest in these things, it is entirely possible for the readers and writers of the mainstream media to pass through the day completely unaware of the ferment bubbling all around them, and this is indeed what happens. The set-up of the cities was expressly designed for this purpose well before official apartheid was implemented, and things remain the same decades after official apartheid has ended. More than that, there is little tangible change detectable anywhere in everyday life regardless of where you are. The fresh air of rebellion seldom blows anywhere beyond the barricades. Housewives, pensioners, pupils, professional and manual workers, the unemployed, are not talking to one another about their situation, their desires and dissatisfaction any more here than they are elsewhere. There is no stimulating sense of expectation, that something new and beautiful is happening, or might happen at any moment. None of the fundamental alienations are openly or coherently challenged anywhere. Even the miserable poverty that is actively fought in streets and workplaces remains taken for granted by most people. When people revolt in the townships their neighbours, more often than not, regard them with indifference if not with open hostility as causing a nuisance. Instances of solidarity are far more rare than the ubiquitous material conditions which encourage it would suggest. The sense of isolation and despair, with no hope of reprieve, is pervasive among the unemployed, professionals and workers alike. There seems to be no way out, and this is reflected in the fact that in Gauteng hanging is the third highest cause of non disease-related death.

Whatever salutary steps are currently being taken by the South African working class; very little of the vast churning going on beneath the surface ever ruptures the whiteout imposed by the established order on all social communication. We have barely begun to lift the censorship by which the public secret of this miserable slave existence is privatised. When the reality of universal social oppression is allowed to assume the appearance of an endless succession of particular, individual disaster, a situation that would naturally produce widespread dialogue and anger instead produces widespread silence and shame.

We remain, by and large, a nation of separated and fearful individuals who are almost completely devoid of real courage, initiative, knowledge about the past and present, with no insight into ourselves, desires, and motivations and precious little practical experience of rebellion against the root causes of our everyday misery. For these and other reasons, dumb submission has us by the throat, and it is that same mute suffering that shackles us hand and foot at every step we take towards a beautiful new life. ‘Those who do not move do not notice their chains’. Those who never stumble through failure after failure never learn to dance in the direction of their real desires. Those who never stutter through the pain of their enslavement never learn to sing the song of their own redemption. Hemmed in by dead-ends on every side, even the paralysis of the current impasse demands a response by threatening to sweep the ground from under our feet. There is no getting used to it, however attractive complacency may be. Few can afford such luxuries in the gilded poverty of the present age. Somehow, we have to do better.

In the 1980s the children of France and South Africa pointed to a direction that seems most promising to us, both for the present and the future.

While the self-activity of wage-slaves scarcely counts as newsworthy today, a great deal of noise is made about the removal of an old statue at a university in Cape Town under the typically nonsensical label of ‘decolonisation’. That all this pretentious bluster about ‘transformation’ is nothing more than a imbecile spectacle is demonstrated by the fact that abolishing the blackmail of school-fees and academic discipline, two elementary oppressions that have inspired exemplary (and far more radical in practice) revolt around the country, has never once been raised.

Protest against the poverty of student life in its economic and intellectual aspects has already mobilised students around the country to shut down campuses altogether numerous times in recent years. As is the case with much rebellion in South Africa and around the world, recent student struggles have already taken on very radical forms. In January last year South Africa experienced three student riots in one week. Just this week all facilities at the University of Kwazulu Natal were closed after a university bus, two other vehicles, a campus residence and the Vice Chancellor’s office were torched in a sustained struggle that produced burning barricades and running battles between students and police over the course of numerous days. Exactly a year ago at the Tshwane University of Technology a bus and eighteen cars belonging to the university were burnt in a struggle against a system that forces young people to pay for the privilege of slaving to adapt themselves to the needs of bosses, and at the Durban University of Technology riots in which buildings on campus were occupied and windows smashed for similar reasons took place throughout the year. Similar events are ongoing throughout the world. During the course of a mere two days during the month of October last year, protests closed down campuses in Nigeria; high school pupils in Zambia improved the country’s 50th anniversary independence day celebrations with enthusiastic rioting; school kids clashed with soldiers in the Ivory Coast; and reports stated that ‘Two Kenyan universities have closed indefinitely after students protested against the recent decision to increase fees without giving prior notice… Students accused both universities of providing poor quality education and using student fees to fund corruption in the institutions…students and police engaged in running battles throughout the day, while students barricaded all roads leading to the universities and destroyed property estimated to be worth several million dollars. Students at Karatina University broke windowpanes and doors and destroyed three buses, over 10 schools vans and several staff vehicles on campus. Events at DKUT were similar, as students destroyed a school bus, personal transportation, ambulances and vandalized a teaching center facility on campus… protests in Kenya have rarely been as violent and destructive as the disturbances on a number of campuses and secondary schools in recent days and weeks…..There have been reports of arson in a number of secondary schools’ dormitories and other facilities. One school’s students are claiming that they burnt down a dormitory as a result of “exam fever”.’ A particularly imaginative action was undertaken in a private university in Chile earlier in the year when ‘During a recent student takeover of the school, Papas Fritas says he took the debt paper records, burned them and displayed the ashes inside a van as an art exhibition…’ Although the debt has not been eliminated by this act, apparently the university will now have to individually sue each student whose promissory note was burned, in order to continue to collect on the student loan debt.

‘AMY GOODMAN: On Wednesday, student protesters used the van that you used to display the ashes of the debt papers during a protest in Valparaíso. News footage showed a driver ramming the van into the barricades around the National Congress. What’s your reaction to seeing this use of your artwork, Papas Fritas?

FRANCISCO “PAPAS FRITAS” TAPIA: [translated] Well, I’m not a moral judge about what the students want to do, nor will I judge their creativity regarding what I donated to them, this object, this artistic work, so they could keep using, because the idea was to always to do a project, an artwork that belonged to the students and as a victory for the students and social movements. It’s not about putting myself in a position of heroism or to be a martyr. Rather, it’s about extending this action. Thanks to a lot of people in this country that have fought against constant dictatorship, people who have been killed by the military dictatorship, as well as by the dictatorship that we call democracy today here in Chile, and people who have been tortured in various ways, thanks to all those people and youth who have taken to the streets, that this work could be completed. This work is a joint effort. It’s a thing that happens in communities facing the same social problems. And it’s by understanding that erotic rush that we are able to feel empathy, a compassion, because of the problems we face as human beings. So what will be happening to the van is not something that affects an individual or an event that is something personal. It’s part of the decisions that they want to take. And in that sense, the only thing I can say is that I support and applaud what they did yesterday.’

Clearly the presentation of ash from debt certificates is far more artistic than that of a urinal with the signature of Damien Hirst, Marcel Duchamp or some other millionaire (Dadaist Duchampagne died with an estate worth $2 million in today’s currency; Neo-Dadaist Hearse currently holds assets upwards of $300 million in value). This cultural superiority can be ennumerated regarding the quality of form as well as that of content; it cannot be quantified in monetary value. The modern world, ruled by barbarism, progresses on the pretense that the life-activity of people like Hearse or Wanksy who successfully traffic in cheap tricks for the amusement and investment of philistine numskulls whose tastelessness is so manifest that they themselves acknowledge it in business terms (one realm where its easy to see the naked truth behind their bullshit facades) by hiring professional art trend-mongers to ‘consult’ them in order to make profitable purchases; brainless bourgeois logic bumbles along on the pretence that such cultural icons are ‘worth’ hundreds of millions of times more than a child who doodles just for the conscious pleasure and unconscious many-sided development it allows her since the kid has nothing in the bank account. Nevertheless, it is true that Tapias exhibition is immeasurably more valuable as a cultural expression than that of any professional artist.

Regarding its content, one can say that a heap of ashes are quite simply an accurate reflection of the world we live in. Firstly, in the sense that it must all be swept up in its entirety during the course of the coming revolutionary storms, secondly in the sense that its main product is waste, from the ashes of Belsen and Nagasaki, the rubble of Gaza and Nigeria, the corpses of Marikana and China, half the food produced on the planet which is thrown away because it’s more profitable in a dump than in people’s stomachs, the reproductive labour of hundreds of millions of women which come to nothing because malnutrition murders scores of infants daily, plastic, poisoned land, air and water, the majority of human labour, the vast majority of commodities whose built-in obsolescence is often pre-empted by the uselessness, or more often perniciousness, of even the functioning product. When the spectator is faced with a heap of ash in an art exhibition, he sees reflected the accurate expression of his epoch, his world, his dreams and his life’s work. The this truth has both an ironic and a pathetic appearance. Ironic in the sense that the slavery which dominates this world, based an uncontrollably accelerated frenzy of production, should specialise most of all in rubbish and destruction. Pathetic in the pathos of Ash Wednesday, when the community of men, women and children across the Catholic population are encouraged to kneel before the altar and recieve a dab of ash on their foreheads as a reminder: ‘Remember, Man, that you are dust, and unto dust you shall return.’ Moreover the content of this exhibition is as Tapia admits the product of a collective reinvention which aimed to create new ways of action and association capable of successfully subverting a miserable situation; it was an act which emerged out of a movement to change life. Lastly, it was a concrete act with concrete consequences: thousands of young proletarians were aided in their struggle against the sort of odious debt which oppresses millions of their fellows across the world.

In its form, this sort of demolition-play is superior to any artwork because the articles in question were presented not to passive spectators but to comrades-in-arms as a contribution to their own struggles. As a salvo in the permanent dialogue of proletarian combat it was communicated as useful material to be further developed in the creation of their own subversive adventures. In the ongoing assembly of dialogue and action it was gifted to the community of struggle as arms to be deployed during their own skirmishes. As is evident, its recipients did not fail to take up the offer. What remains is to put such promising actions, which for all their limitations represent at least a start, a rupture from the dreary facade of social peace which has reigned for the last two decades, in the service of an equally radical content.

At present, however, such struggles remain limited to very paltry demands regarding provision of student loans, scholarships, and so on. Despite having developed, during the second half of October, into a nation-wide movement involving all the major public universities in the country holding demonstrations throughout every major city, South African students still desire nothing more than the reversal of a proposed fee increase. A far cry from the recent proposal of professor Denis Rancourt in terms of minimum demands that ‘At the very least, students should be PAID a salary, and allowed to unionize as workers.’ Before anyone begins babbling about such demands belonging to some sort of socialist utopia, it should be pointed out that this state of affairs (minus the unionisation, which is irrelevant anyhow) already exists – in Saudi Arabia.

Against the intellectual poverty to which they are routinely subjected, students at the Pretoria campus of the Medical School of South Africa went on strike in early 2014, blockaded the entrances to campus, broke into and occupied the administration buildings and overturned a vehicle in a struggle against a system that everywhere forces young people to submit their minds to the arbitrary dictates of bureaucratic authorities. Their demands, however, remained limited to the most obvious manifestations of this system, in the form of particularly unpopular professors. Around the same time, on the streets of Johannesburg, hundreds of high-school pupils rioted and looted in an attempt to put an end to the still wide-spread use of corporal punishment, among other things. The system of discipline and punishment as a whole, which has nothing to do with education and everything to do with obedience training, was not thrown into question, despite the fact that now, for the first time in the history of this country, a widespread challenge to the practice of testing rote learning along with the role it plays in schools and education generally is being mounted — by primary school teachers. This month, the workers of all five teachers unions announced that they would refuse to administer the Annual National Assessment tests imposed by the state on the grounds that ‘The system encourages teachers to “cheat” by cramming students with soon to be forgotten information that can be regurgitated on the test date. Good, but fundamentally meaningless, scores benefit only the authorities.’ Although presented by the unions as if they were responsible for this decision by ‘appealing’ to the teachers to carry it out, the officials were doubtless trailing behind the rank and file in the same way as the ANC when these illustrious leaders of the liberation struggle ‘instructed’ the South African masses — from their safe headquarters in Lusaka, thousands of kilometers away from the blood and fire — to ‘make the townships ungovernable’ after these leaderless masses had already begun to do so themselves. Although their continued toleration of reprehensible representatives and their continued failure to speak for themselves (of course both the ‘alternative’ and the ‘mainstream’ media hardly ever communicate what workers have to say) means that it is difficult to get an accurate understanding of the true state of affairs; the likelihood that this admirable insubordination has been imposed on their unions by workers themselves is suggested by the fact that teachers and other state employees were among the first workers to confront on a large scale the servile position of the unions in relation to the ruling party by forcing the union leadership into what remains the biggest strike in South African history in 2010. Despite the fact that the objections of primary school teachers are no less applicable to high-schools and universities, which are just as much turned by exams and ‘a system of marks that might contribute to a “league table” of competing schools’ into places ‘where you follow meaningless procedures to get meaningless answers to meaningless questions’; despite the possibility of rebellious youth making common cause with their own rebellious teachers on this basis, a possibility more palpable today than ever before now that thousands of pupils and education workers have begun to elaborate a practical critique of a system of teaching that, in the words of Free State University vice chancellor, Jonathan Jansen, amounts to amounts to “the education equivalent of force-feeding an under-nourished patient on junk food”; students remain firmly in favour of keeping things exactly the way they are, going so far as to side with the state in its conflict with the teachers, as is the case with the Congress of South African Students which “indicated…that there was no hostility towards ANA by learners and they would be happy and ready to write the assessments this year in December”. However questionable the claims of these clowns who speak in the name of 7 year old kids may be; it is an unquestionable tho regrettable fact that an end to the compulsory miseducation of young people has not yet been placed on the agenda in any of the many recent struggles in this country. Unfortunately, exam fever has yet to strike South Africa.

Yet, in the struggles of the 1980s schooling was largely understood as counter-revolutionary indoctrination, revolution was declared to be the proper school for the oppressed, and education was considered worthless at best and more likely downright harmful unless it had to do with preparing young people for taking charge of every aspect of their lives. From the moment when Ongkopotse Tiro, one of the leading participants of the Black Consciousness movement, was expelled for tabling this proposal in 1973, to 1986 when Zwelakhe Sisulu spoke of ‘People’s Education for People’s Power’, the idea of schooling as it exists in the top-class white institutions – ‘education for oppression’ – was rejected with disgust. And unlike many pseudo-revolutionary student movements around the world, where radical rhetoric is donned as a fashion statement as long as it does not interfere with one’s qualifications, South African youth meant it: they boycotted classes so long the flower of a generation never bothered going back, then burned the buildings to make sure they couldn’t be used against them. They got jobs in factories in order to conduct sabotage and organise strikes. They expelled the cops and the local government from their neighbourhoods by force of arms and set up experiments in self-organisation on a street by street level, co-ordinated geographically via meetings of delegates.

Unfortunately, although politicians, cops and bureaucrats in league with the apartheid state were held in contempt, free reign was given to all the others, leading inevitably to the replacement of working-class self-activity with political wrangling by parties, unions and other rackets leading eventually to the vicious turf-wars of the late 80s-90s between minions of the UDF, AZAPO, IFP and ANC.

This is where their comrades in France have demonstrated some beautiful and perfectly complimentary suggestions. If the children of South Africa organised their anger in an exemplary manner, they failed to do likewise with their dialogue. Where dialogue is lacking, it is always replaced by monologue. In place of free and extensive many-sided discussion among themselves, the struggles of the era were dominated by the one-sided contemplation of the speeches and images of revolutionary specialists: struggle celebrities like Nelson Mandela, Steve Biko and Chris Hani. These images and this monologue continue to weigh like a nightmare on the brains of the living.

The children of France did not organise their anger to a degree anywhere near the extent or intensity of their South African comrades. But what they lacked in that department they gained in dialogue. During a series of university student mobilisations against a particular law, the ‘Devaquet Bill’, teenage apprentices (‘lascars’) at a technical high-school seized the opportunity to begin a remarkable movement of their own. In doing so they invited the students to join them, but only if they were willing to renounce the sort of top-class ‘education for oppression’ to which South African students today, even at their most militant, universally aspire. It was during this moment that social communication flowered through the streets in the form of pamphlets, posters, graffiti, banners, leaflets, placards and most especially passionate conversations among all and sundry the likes of which has not been seen in South Africa for at least a full generation. (A sample of these documents provides a small taste of what this was like: see Appendix On Proletarian Communication) These discussions emerged precisely because people had started talking to each other without the intermediaries who are usually allowed to (mis)represent and ‘lead’ them: ‘We want a wide open debate with no taboo. Everyone will have an equal right to speak. Now is the time to dare to say everything. But be warned – we won’t tolerate any trade-union, party , petty chief or bureaucrat.’

The marvellous message of the apprentices to the students is particularly relevant in this country at the present moment as the phony dream of a better future being sold to the victims of universities and colleges has never been more threadbare. Firstly, much more students fail to finish their studies in South Africa today than was the case in France back then. According to the Department of Higher Education and Training’s first annual statistical report, published in 2013, the graduation rate for South African university students is 15%. Of those few who do graduate, education inflation has devalued the worth of these qualifications; the world economic crisis has reduced demand for them; ever faster changes within the process of production has reduced the status, prestige, and working conditions of many white collar jobs to a level scarcely better than manual labour; 80% of the income from these jobs simply goes to service basic consumer debt such as housing, which alone accounts for on average 50% of household expenditure. Bitter strikes by public sector workers (the education and health workers, managers, clerks, engineers and journeymen who now form the majority of COSATU membership, which was, as late as the 90s, mostly blue-collar) in 2007 and 2010, the latter involving nearly one and a half million state employees and a loss of 20 million workdays, demonstrates the desperation felt even by this supposedly privileged strata of wage-slaves. It should be clear that the above historical examples are by no means presented here as complete and adequate models to be imitated. Even if such a feat were possible, the limitations briefly pointed out demonstrate the fact that there are no easy answers to be found in the past – or in the present, for that matter. They simply indicate the level of self-activity that can, under certain circumstances, be attained, and that must, anyhow, be surpassed. Despite the relatively promising indications detectable here and there, we have a long, long, long way to go.

Siddiq Khan

19 September 2015

Nyala after. Vuwani, Limpopo, August 2015

Nyala after. Vuwani, Limpopo, August 2015

For more information on the struggles in South Africa see “South Africa: A Reader” here on this site

Appendix On The Militant Student

(Added 3 October 2015)

As a welcome (though, as will be seen, severely limited and thoroughly inadequate) step in an altogether more promising direction than the previous focus on images of the colonial past, the leftist student movement in South Africa seems to be moving in a similar direction to the position that emerged during the revolutionary occupations movement in France — but without the occupations movement! In Cape Town there is a nominal occupation tolerated by the administration but no participation by anyone. I visited once at night and there was all of five people actually staying there doing nothing other than hang around surfing the net. There are a number of passive spectators that attend lectures and events organised by the active militants but the notion of everyone running their own affairs seems not to have entered anybody’s heads at all. To be fair, there are plenary sessions called to discuss proposed steps forward, but I am not sure whether this is very different to the consultation meetings implemented by unions, bosses and government where decisions already taken by the leadership are presented to the masses, with only the details up for discussion. Without a base of ongoing dialogue within a common space inhabited by the bodies, dreams, arguments, desires, passions and plans of those who participate in a shared project, I don’t see how it could be otherwise.

You will notice from the announcement reproduced below that there is also an artificial separation between intellectual and manual labour — students performing intellectual and clerical work called on to strike instead of manual workers rather than in solidarity alongside them, which is an admirable attempt to turn the ‘privileged’ bestowed on a fraction of workers by the established hierarchy against the establishment itself, but also seems naive in the expectation that the ‘privileged’ will be allowed to conduct such activity with impunity. If their strike proves harmless to the normal functioning of the institution, it will, like the removal of the statue, be tolerated. A one day symbolic strike promises to do just that. Since the stakes involve considerably more than mere statues, however, such symbolic action is also likely to prove entirely ineffective. The moment so-called privileged student workers take any steps that seriously threaten to achieve their stated aims these pseudo-privileges will evaporate faster than a snowball in hell. Moreover, the perspective that workers lower in the hierarchy are mere ‘victims’ leads to an attitude that those ‘better off’ do not suffer any poverties of their own that they need to struggle against for themselves, and thus reproduces the old militant role that aims to substitute one’s own actions for the self-activity of supposedly helpless victims.

This is precisely what has always separated white leftists from the struggles of blacks since the days of apartheid, as illustrated so incisively in Rian Malan’s My Traitor’s Heart. But it was also one of the main limitations of the revolutionary movement in France during the May days of ’68, as noted by R. Gregoire and F. Perlman in Worker-Student Action Committees. Those who spare their own everyday life and conditions from the blowtorch of practical criticism do their masters a big favour in supporting the pretence that only the most obvious, ‘marginalised’ aspects of the dominant slavery need to be destroyed, as if poverty is an exceptional and unfortunate by-product of an imperfect but basically good system (and what system is perfect? ask the guardians of the reasonable) that needs nothing more than the activism of good people in order to be reformed, improved and, one day, with the Grace of God, perfected.

The separation between everyone and the power to determine the conditions of their everyday existence (a power possessed by no-one precisely because an irrational division of labour between isolated producers of commodities is violently enforced by the lackeys of capital) will only be reinforced as long as this universal productive power is treated as the exclusive property of a particular fraction of the population — whether it be the bosses of a firm or the workers, the students of a school or the administration — rather than, in the unforgettable words of some long-dead poor and oppressed people of England, ‘a common treasury for all’.

The RhodesMustFall movement, in solidarity with UCT workers and other progressive organisations at UCT, join the October6 collective at WITS and UJ in embarking on a day of collective radical action in echoing their clarion call for the widespread end to outsourcing and the immediate implementation of a dignified living wage at all public institutions.

In solidarity with workers at public institutions across the country, RhodesMustFall specifically calls on all students employed by their respective universities to “Down Tools” on the 6th of October 2015 as we band together to demand that insourcing become a principled commitment of the decolonised African public university.

Let all students who work as tutors, secretaries, subwardens, teaching assistants, librarians, research assistants and more refuse to work for their universities for this day, utilising the positionality and the power we have within the university to raise awareness and solidarity about these issues, without the dire risk that the workers would face for embarking on an unprotected strike.

[…]

October 6, 2015 should be noted as a turning point in the history of staff, student and worker relations at public institutions in South Africa if we can successfully gather together to protect and prioritise the voices and struggles of the most marginalized and victimized members of our respective universities, the workers.

STATEMENT

#RhodesMustFall speaks: Why we disrupted Piketty

1 October 2015

The #RhodesMustFall movement in collaboration with the UCT Left Students Forum coordinated a demonstration that disrupted the “public” dialogue with economist, Thomas Piketty, who has been invited to deliver the 13th Nelson Mandela Annual Lecture in Johannesburg later this week.

Piketty was due to deliver a talk on “Income, wealth and persistent inequality” at the University of Cape Town via livestream from Paris. It was to be preceded by introductory addresses by UCT Vice Chancellor Max Price, former finance minister Trevor Manuel and former UCT Vice Chancellor Njabulo Ndebele, and followed by a panel discussion involving various lecturers and professors from institutions around the Western Cape.

Although many may wish to deny it, the year of 2015 in Higher Education at historically white institutions has been the year where “Decolonisation” has been thrust into the tired imaginations of administrators and “intellectuals” who have failed to lead South Africa towards a more positive trajectory and have succeeded spectacularly in developing one of the single most unequal societies on the planet.

The #RhodesMustFall movement, amongst many other revolutionary organisations, has been born and sharpened out of such a climate.

As the discourse surrounding “decolonisation” thrust forward by this particular movement begins to gain traction both nationally and internationally, we have begun to push harder on our commitment to the exploited and outsourced workers at UCT -whose voices, like ours, have been brutally suppressed for far too long.

This campaign against outsourcing is undertaken with clear continuity from RMF’s campaign demanding justice for Marikana in light of our home institution’s complicity through its persistent exploitation of workers, and it’s continued investment in a colonial legacy of social, political and economic violence that it steadfastly refuses to take responsibility for.

In 1999, UCT became the first public university in South Africa to begin outsourcing the labour of workers on its campus – soon to be followed by all other major universities in the country. Thousands of workers who clean, cook, tend gardens and sustain the day-to-day existence of these universities in countless other ways were suddenly no longer employed or paid directly by the institutions on whose campuses they work every day, but “outsourced” to receive their salaries through external private companies contracted to broker and oversee their labour.

Such companies include the likes of Supercare, Metro Cleaning Services, TurfWorks, C3SS Security, and the notorious security company G4S, who have been found guilty of human rights abuses the world over. These businesses make substantial profits from acting as ‘middle-men’ and paying workers poverty wages.

The advent of outsourcing saw workers immediately having their salaries cut by up to 40%, losing job security and losing the benefits they had once received as direct employees – including the right for their children to attend university for free.

The ideological motivation for the introduction and continuation of this exploitative practice is the idea that universities should be run as businesses, focusing on their ‘core function’- academia. Workers and the jobs they do are deemed ‘peripheral’ and handed over to external companies to manage.

This allows the university administration to deny any responsibility for the wage exploitation, abuse and victimisation of workers on its own campus. Additionally, the justification given by the management of these institutions for this practice is to decrease costs to keep fees low for the sake of students – almost all of whom are unaware of the conditions workers are facing in their name – all while these same administrators take home salaries which are sometimes, as with many university vice chancellors such as Max Price, in the order of millions of rands.

Exploitative treatment of workers is a fact of all outsourced companies. The only real solution is to end outsourcing and hire workers directly.

Looking once again to the background surrounding the day’s events, we remember the legacy of Leander Starr Jameson, after whom the venue for the talk – the pantheon that is Jameson Hall – is given its name. Jameson was a medical doctor in the late 19th century and who had used his reputation to facilitate the dispossession of Africans at the hands of none other than Cecil John Rhodes. This, among many other dimensions of Jameson’s legacy including acts of targeted violence, provide the backdrop through which the #RhodesMustFall movement is prompted to reject his memorialisation, particularly in the context of a conversation with an author such as Piketty, whose central thesis addresses the issue of legacies, inheritance and their relation to capital.

In fact, the #RhodesMustFall movement is acutely aware of Piketty’s case study on Marikana in his acclaimed book, “Capital in the 21st Century”. We critique his failure to adequately consider the intersectional dimensions of the people involved – be it race, gender or otherwise. Nonetheless, the fact remains that his conclusions surrounding inheritance and its relationship to growing inequality can and will be taken through to their logical conclusion by RMF and other revolutionary organisations.

Due to technical difficulties, Piketty was not even able to give his talk at UCT via livestream. Instead, Trevor Manuel facilitated a discussion between panelists which was then interrupted by a second wave of RMF and Left Students Forum protesters -we returned this time to deliver a statement highlighting the demands of the outsourced workers and commemorating the recent passing away of Mam’Victoria “Dledle” Luzipho, a Supercare worker at UCT whose death went unacknowledged by the institution but was reported on by UCT multilingual student newspaper Vernac News. In their words: May your soul rest in peace Mam’Victoria. Sizohlala sikukhumbula.

All the while Trevor Manuel antagonised our protesters and called for order even while facilitating an event that clearly cared little for resolving or even acknowledging the inequality in front of our eyes.

Ironically, the only workers who were present for this talk on “inequality” were outsourced security guards standing in and around the venue – employed by none other than G4S.

The #RhodesMustFall movement now asks the question, “What does it mean when UCT excludes the most marginalised members of its community from conversations that directly affect their lives?”

Through these considerations the #RhodesMustFall movement, along with the UCT Left Students Forum, took this opportunity to pressurise the university into providing the material substance and political will required to improve this deeply unjust landscape in which the ivory tower of UCT finds itself. This is especially the case as UCT is presently in an active dispute with the National Education, Health and Allied Workers Union (NEHAWU) over demands that seek to tangibly change the living conditions of workers at the institution.

The decision of the university regarding the dispute will be released by the University Council on 5 October 2015.

The basis for this consciousness raising intervention lies heavily on the ongoing work initiated by progressive staff, student and worker organisations at the University of Witwatersrand and the University of Johannesburg in calling for an end to outsourcing across public institutions, along with the immediate implementation of a dignified living wage. RMF and other progressive organisations at UCT have since joined in making this clarion call. Such demands cannot be deemed anything other than vital in our collective conceptualisation of a truly decolonised university.

A day of national action in calling for these demands at public universities across the country has been set for next Tuesday: this is the #October6 campaign. At UCT in particular, should the university decide not to end outsourcing or implement a dignified living wage in its decision on the 5th, the #RhodesMustFall movement and allied organisations will proceed to the #October6 mobilisation efforts in full force.

We will no longer stand for the hypocrisy of an institution that hosts elite talks about inequality whilst outsourcing and exploiting its own workers.

#RhodesMustFall in solidarity with Decolonise Wits, UCT NEHAWU Joint Shop Stewards’ Council (JSSC), the UCT Workers Forum, the UCT Workers’ Solidarity Committee and UCT Left Students’ Forum (LSF)

Appendix On Proletarian Communication

From France Goes Off The Rails, 1986-1987

WHAT TO DO?

Over the last few days many things have been happening in the streets and in our heads, we’ve gotten to know each other better, we’ve been thinking, we’ve discovered a lot of things. We must talk about all this. We are strong because we are many and stand together. And we stand together because despite our personal history and our unique identity, our experience has been the same and our future is the same.

We must talk between ourselves to clarify everything: what we want, what we don’t want any more, why we took action in the first instance and how to carry on. We need a place to do this; we’ve found it: it’s our school. It’s ours’, they’ve said so time and time again. We take it at face value and the school too.

Then we need to organize and unite around what we want. Define who are our friends are, get closer to them, who are our enemies and brush them aside.

We think we must rapidly get close to other LEPs who are in the same boat as us, but also to all the youth and older people already at work or on the dole because “they’re us and we’re them”. A few months or years ago they were where we are; if nothing changes, we’ll be in their position in a few months or a few years.

We think we must join forces with the students, but on a clear basis, stating who we are, what we want and impel them to clarify their position (see: ‘We criticize!” ) .

We think we have things to say to our teachers, some nice, some not-so-nice, for instance that if they can teach us some things, there are other things they should learn or re-learn from us.

We think we have a lot to say about work, i.e. about money, and as money is at the heart of society and weighs on the entire society we therefore have to say it to the entire society and first of all to our parents.

So here is what we propose. First we occupy the school, organize it and talk between ourselves. When once agreed on certain essential things, we’ll go and meet other LEPs to do with them what we’ll already have done together. Then we join the students in the streets on an equal basis. This is just a start…

To start the discussion we have prepared leaflets and we propose to talk about them in order to improve them, modify them, turn them inside out and/or write others. We want others to contribute and that everybody, teachers and staff included, has a say. We want a wide open debate with no taboo. Everyone will have an equal right to speak. Now is the time to dare to say everything. But be warned – we won’t tolerate any trade-union, party , petty chief or bureaucrat. Let it be known !

LIKELY LADS, LES LASCARS, L.E.P. ELECTRONICS

*

THEY WANTED TO TURN US INTO PRATTS…THEY BLEW IT !

We started walking out when the sound of the students’ movement reached our ears . At first we didn’t quite catch on. What were the students fighting against? We didn’t know. But they were fighting against… something — and we liked that.

We took to the streets to break with the tedium of school and because we too were violently against…something! But What ? Well, this was still to be defined.

When we took to the streets we brought with us all we liked at school – our friends, our mates, laughs, joy, friendship. We talked to each other as never before and we really bloody enjoyed it. So school wasn’t the four walls. It wasn’t the curriculum ?

IT WAS US ! ALL TOGETHER !

By speaking, running, thinking, talking, quickly, very quickly, we’ve understood a lot of things.

The students are fighting the Devaquet Bill which tightens the selection for university where we’ll never go! Yet we know about selection! We’ve already been up against that. Very early, “clever” people have orientated us towards short courses at the L.E.P.’s (technical colleges). We were really made to feel we weren’ t good enough to do anything else and that it would be even worse after leaving school – that is, if we could find a job. We gather the “Monory Bill” is relevant to us and that it too will make things worse. Worse than what ? How ? We don’t quite see !

Anyway ~ don’t need to know about this bill to reject it! We no longer want what we have – it is despicable. So we’re not going to ask for more or less of it. More of what ? Less of what ? What the hell does it change ? To be more profitable for those who want to keep our noses to the grindstone ? No thanks !

WE’RE NOT INTERESTED. FIND SOMETHING ELSE !

The teachers fostered in us (without much conviction) the illusion that our certificates – providing we were hard-working, punctual, attentive, conscientious – would enable us to find a position, oh, not a brilliant one, but a position nonetheless. They had us believe our studies would condition our place in the labour market. It seems to us instead that our future job already conditions our education.

SOUNDS PROMISING, DOESN’T IT ?

We thought we could get away from it through music, travel, theatre, friendship , that kind of thing…. that we’d manage somehow, without knowing how to escape. Meanwhile we just kept quiet in order not to offend them, not to annoy them…. but also because deep inside, we knew we were stuck, alone, isolated.

Now we know : it wasn’t a personal or individual problem, it’s our problem – all of us ! By refusing school, passively yesterday, actively today; it is work and the shitty lives they’d nicely prepared for us we refuse ! We talk, we think, we laugh,

YET WE’RE VERY SERIOUS!

You nearly got us; you blew it!

We’ve caught a glimpse of something else, we’re gonna go all out, the shit’s gonna fly!

LIKELY LADS, LES LASCARS, L.E.P. ELECTRONICS

*

SOME GRAFFITI TAKEN FROM THE WALLS OF PARIS, BEGINNING OF DECEMBER 1986

We’ve all been infected with mental Aids: it’s normal, considering the time we’ve spent being fucked by the government.

Cadillac arrest on Saturday.

The only freedoms we possess are those the government can control the use we put them to.

And if we did re-make the world…

Isolated…killed off

We want an explosive scandal and to explode ourselves (LEP school apprentices).

Be cruel.

Open the prisons.

5 cars are blocking the street, today they open the debate.

Tonight all Paris must be outside communicating.

If you remain all your life crushed and exploited, then you’ll understand the reaction in the streets.

Press mess.

Another cross drawn up on the pigs’ slate, shivers run down my spine.

Anger must come before something I find hard to be precise about [placard of an arab on the 10th December demonstration]

Paris belongs to us.

Me cold? Never!

Open your eyes, switch off the tv.

Time shall not pass.

The same wave rushes through the English streets & ghettoes (& in all Europe) but the international media won’t tell you about it because they’re afraid of our strength. Therefore, English ‘jeunes’ send you strength, support and eventually victory. [written in English]

Non-strikers are ‘Les Miserables’ [on a statue of Victor Hugo]

*

“EVERYTHING CRITICIZABLE MUST BE CRITICIZED”

WE CRITICIZE !

STUDENTS, we took to the streets with you yesterday but we might as well tell you now: we don’t give a shit about the Devaquet Bill !

For us selection is over, university is closed to us, our certificates lead us straight to the factory after a stretch on the dole.

As far as we are concerned, critique of the Devaquet Bill is useless:

We criticize university,

We criticize students ,

We criticize school,

We criticize work.

School gives us the bad jobs.

University gives you the indifferent ones.

Let’s criticize them together !

But don’t tell us: “workers, road sweepers will always be needed”. Or come on lads, take those jobs. You’re welcome to take them, don’t be shy!

WE’RE NOT ANY MORE STUPID THAN YOU, WE WON’T GO TO THE FACTORIES !

If you criticize the Devaquet Bill which only makes a bad situation worse, you haven’t understood anything! Besides, you aren’t much better off than us. A good number of you (60%, we heard) will give up before graduation and these “bad” students will go straight to the shitty badly paid jobs which is our lot. As to the “good” students, they’ll find out the middling jobs they’ll get (you can’t find the good ones at university) have lost a lot of their prestige and power. Nowadays a doctor is no longer a “Sir”, he’s just on the Social Security’s pay-roll. And what’s a teacher, a lawyer ? There’s so many of ,them…!

STUDENTS, if you criticize only the Devaquet Bill and not the university, you’ll be fighting on your own and the bill will go through parliament all at once or bit by bit and then YOU’LL ALL BE FUCKED ! And if by chance it doesn’t go through at all everything would be just as before and half of you would end up in offices, in YOUR tidy factories.

STUDENTS, you’re being called on to run this society and we to produce it.

IF YOU MOVE, IF WE MOVE, THEN EVERYTHING CAN MOVE.

But if all you want is to dutifully run this society, and on the cheap become social workers, team leaders, heads of personnel, executives, sociologists, psychologists, journalists, work inspectors, in order to educate us , counsel us , direct us , inspect us , inform us , lead us , make us work tomorrow….

THEN FUCK OFF !

But if to begin with you want to criticize the educational system which excludes us and debases you, if you want to struggle with us against social segregation and poverty -yours and ours -then…..

BROTHERS, COME WITH US? WE LOVE YOU !

LIKELY LADS, LES LASCARS, L.E.P. ELECTRONICS

A Chronology of significant events in South Africa over the last month

18/8/15:

South Africa, Gauteng: cops fire rubber bullets at schoolkids peacefully protesting racist schooling

19/8/15:

South Africa, North West: construction workers “go on rampage”, angry about wages…Western Cape: buses burnt in taxi driver protest…More here

On The Buses

24/8/15:

South Africa, Cape Town: protesters demanding electricity burn tyres, loot shops, throw stones at cops “Two violent protests rocked Cape Town on Monday, causing traffic jams and resulting in 21 arrests. Protesters were burning tyres and throwing stones in Klipheuwel Road near Philadelphia, while the busy Bunga Avenue near Langa was closed for traffic….about 100 people took to the streets, and cops were forced to close both on and off ramps from the N2 onto Bunga Avenue….Meanwhile, violent protesters clashed with police at Klipheuwel Road informal settlement. Residents blocked the road and demanded water and electricity….protesters burnt tyres in the street, looted shops and pelted cops with stones…Police fired rubber bullets to disperse the crowd…A Mvalo security vehicle was also damaged by the mob. A cop at the scene said the security company works for the nearby power station, the same place where protesters burnt down and cut some power cables earlier this week. ”More here “…tyres and debris were set alight and scattered in the streets on Monday morning. … on Friday night….residents from the Klipheuwel township set fire to the substation, plunging that section of Durbanville into darkness.”

25/8/13:

South Africa, Cape Town: hostel transformation project suspended due to protests about housing allocation “…a group of youths campaigning for a change in the agreed-upon housing allocation for this hostel project had intimidated members of the project steering committee.”

26/8/15:

South Africa, Eastern Cape: Black Students Movement occupy Vice Chancellor’s office “… these universities continue to benefit the elite, continue to punish the children of the black working class, families from townships from rural areas and informal settlements. The United Front calls on the Black Student Movement to come together and join up in a nation student initiative to build a new independent student movement so that these battles can be fought in a nationwide scale.””

1/9/15:

South Africa, Limpopo: roads closed after night of looting and burning of businesses “…residents continued to protest against planned inclusion into a newly demarcated Malamulele Municipality….a total shutdown in the area saw schools and businesses closing down as the protests turned violent… several businesses were looted and some burnt down. These include two hardware stores, two bar lounges and a butchery…there was no public transport in or out of the area as roads were barricaded with tyres and rocks. On Monday police fired rubber bullets to disperse crowds “…Cape Town: semi-homeless burn tyres, block roads in movement for housing allocation rights “Langa backyarders have burnt tyres and thrown rubbish in Bhunga Avenue, blocking several roads hoping that the City would include them on the list of beneficiaries for 463 houses being built in the area. On Tuesday an office of the City’s disaster risk management was damaged by the protesters and three people were arrested for public violence. “…Western Cape: student movement protesting 50% Afrikaans language policy hots up It should be noted that this is dominated by millionaire & demagogue Malumele’s EFF party, and comes almost 40 years after the Soweto uprising which started as a protest, totally independent of all formal organisations and political parties, against the state’s insistence that high school kids be taught in the language of the oppressors (Afrikaans). See in particular the section “Reflections On The Black Consciousness Movement and the South African Revolution (Aug. 1979) – here.

2/9/15:

South Africa, Limpopo: 3rd day of clashes as locals demand mining jobs “More than 500 residents in Malabana, a rural village north-west of Polokwane, halted traffic for several hours with burning tyres on Wednesday to demand jobs from the company mining on their doorstep. The premier producer of platinum in the world is faced with revolt from communities. Officials have, since Monday, had to be escorted by police to the site. The protest started on Monday after residents complained they were not considered for job opportunities on the mine. Protesters burnt the local clinic and vandalised garbage bins. Police had to use rubber bullets to disperse protesters and made 11 arrests on Tuesday….they did not have water in the area, and had to rely on contaminated stream water. When the struggle ensued with police on Wednesday, residents said police fired rubber bullets and broke some residents’ homes. A furious Maria Ledwaba of Ga-Molekane said police broke her door and forcibly entered her house and broke her wardrobe because they accused her family of hiding protesters. “

3/9/15:

South Africa, Gauteng: workers furious for not being paid burn 4 trucks, attack municipal building, block roads with fires, etc. “… as the fire engulfed the vehicles, the workers, employed under the Vat Alles programme, angrily threw stones, smashing the windows of two other bakkies. Missiles also rained down on the municipal building, as the workers smashed office windows with stones and damaged furniture. Computers, desks and chairs were wrecked and then the workers turned to the streets. One uprooted a road sign and hurled it into the fire….”…KwaZulu Natal: students shot with rubber bullets and pepper sprayed in protest against enrolment fees etc.

4/9/15:

South Africa, KwaZulu Natal: high school students riot after principal fails to give reports because parents hadn’t paid fees “An Overport principal’s car was trashed, and school property was damaged, when Grade 12 pupils went on the rampage because they were not given their reports on Friday afternoon. The principal… had not released their reports because their parents had not paid fees. As a result, they were unable to submit their university applications in time. Police arrested a 19-year-old matric pupil who threw bricks at officers and their vehicles. “

7/9/15:

South Africa, Limpopo: “violent” protests demanding jobs enter 2nd week “Running battles continue, roads around the mine are blocked leading to disruption of schools around the area.”

8/9/15:

South Africa, Limpopo: 20 buses burnt and satelite police station vandalised etc “Violent protests by residents of Mapela outside Mokopane, Limpopo, entered its second week as residents demanded jobs and community projects from mining company Mogalakwena Platinum Mine, owned by Anglo American Platinum. Learning at schools was disrupted as residents continued to block roads and vandalise properties in the area. …In another protest, buses were burnt down overnight in Marapong, Lephalale. At least 20 buses were reportedly set alight and a satellite police station was also vandalised. …In Vuwani, residents looted shops and vandalised property as they continued protesting against being included in the newly planned Malamulele Municipality.“…Mpumalanga: residents demanding jobs block road next to police station

9/9/15:

South Africa, Rustenburg: shops looted as residents block roads demanding municipality deal with sewage and allocate housing Invariably the reporters portray looting as being purely against foreign-owned shops, whereas often these are the only shops in the area or sometimes other shops are also looted but are not mentioned because it doesn’t help the journalists’ agenda to portray the looting as xenophobic. Which is also not to say that sometimes xenophobia plays a part.“These shops are expensive and they do not give us credit, that is why we loot them” …The group started blocking roads in the township with rocks and other objects following a meeting in which a resolution was apparently taken to block all entrances on Wednesday morning to prevent people from going to work or school.”

10/9/15:

South Africa, North-West: youths burn down tribal office in protest demanding jobs More here and here

14/9/15:

South Africa, KwaZulu Natal: vehicles and building set alight as students get angry over lack of accomodation & ending right to pay debts in instalments whilst continuing studying “Students damaged buildings and burnt at least two cars at the University of KwaZulu-Natal’s Westville campus on Monday in protests that again focused on funding and lack of accommodation. Roads near the campus were barricaded with rocks, turning the area into a traffic nightmare. Five campuses across the province were involved in the protests…Students emerged occasionally from residences to hurl stones and bottles at the university’s security guards …Campus security guards, known by students as the Red Ants because of their red uniforms and black bullet-proof vests, were armed with crowd control weapons similar to paintball guns. They used tear gas on Monday to fend off the students. The students used ironing boards as shields against the crowd control weapons. The smell of charred wood and melted metal hung over the campus, with the two burnt vehicles, twisted by the flames, in front of the university’s Risk Management Services offices. The offices had also been damaged by fire. Campus security came under attack from stone- and bottle-throwers who hid in the residences.” More here, here “Rubber bullets were eventually fired to disperse the throng that attacked police with stones and bottles. Fire Department officials were also at the scene after a bus parked on the campus was set alight. Several buildings on the main campus in Alan Paton Road were damaged after students threw rocks at the windows” and here “the main administration block was set alight. Protests continued through to Monday morning with the police’s Public Order Policing unit being deployed. Two cars were also torched and numerous tyres were set alight and staff arriving for work in the morning found the entrances blocked by protesters.”…Durban: roads blocked with burning tyres etc. for over 5 hours in protest over lack of electricity…Cape Town: local state destruction of homes met with stone throwing v. rubber bullets…report on illegal occupation of houses…Gauteng: workers demanding unpaid back pay blockade ANC regional executive committee and staff in building

15/9/15:

16/9/15:

17/9/15:

South Africa, Western Cape: arrests after strikers burn down and destroy warehouse…KwaZulu Natal: authorities close down all student facilities, on or off campus, after campus residence is burnt down in continuing protests about debts “Thursday, a Westville campus residence was torched and students staying there were taken to other residences. On Monday night, a private bus which the university contracted to transport students was burnt to ashes. On Sunday night, two cars and the building which houses the office of vice-chancellor Albert van Jaarsveld were torched. Police spokesman Thulani Zwane said at 2.05am on Thursday, a group of people wearing balaclavas set a laundry building at the Westville campus alight. About five rooms and the laundry were set alight while students were sleeping inside….After the announcement on Thursday that students had to leave, violence erupted at the Pietermaritzburg campus where a car was overturned.”

19/9/15:

South Africa, Johannesburg: report about clever method of opening upmarket squats

Footnote by SamFanto

1 I really can’t agree with this – any look at the period up until 2005 (and I can’t see that things have significantly changed much since then) shows how devastating neoliberalism has been for the working class – see the introduction to this.*

Footnote to footnote by SK.

* Maybe SamFanto’s definition of defeat is different to his. It seems to me that ‘how devastating neoliberalism has been for the working class’ precisely constitutes the accumulation of grievances Alexander mentions. Obviously, such an accumulation hardly constitutes a victory, but if you don’t fight against something you can’t be defeated, and maybe this is what he means. You can hardly say the working-class response to the ruling party’s neoliberalism has been particularly vigorous up until now. That is precisely the point: we are entering a moment where the deflection of proletarian anger hitherto accomplished by the ‘Mandela magic’ of the ANC with near complete success has finally begun to falter. The real battle, and consequently the real possibility for victory or defeat, is only beginning…

Leave a Reply