This comprises a translation of 2 short texts – one on the recent revolts in Guandong, the other about resistance to nuclear power, followed by a list of some of this year’s events.

1:

The events in Guandong, September 2016

13th September 2016

China, Guandong: heavy clashes with cops as villagers protest arrest of mayor “…the village was now in police lockdown, and internet connections were down. Videos obtained by Hong Kong’s RTHK from villagers show hundreds of police in riot gear confronting at least several dozen villagers marching with Chinese national flags on Tuesday morning….the police had used tear gas and rubber bullets in the operation. …The RTHK footage also showed villagers throwing rocks at huddled ranks of police equipped with riot shields….In 2011, Wukan made international headlines when villagers ransacked the police station and government offices in protest against landgrabs and corruption. After months of demonstrations, the government fired the former village chief and villagers voted in many protest leaders.”

Another video here

The following was written in French by Lao She (Old Snake), who knows China; translation by me [SF], from here:

Wukan:

strengths and weaknesses of the opposition to the expropriations in rural China

To understand anything about the latest riots in the village of Wukan, you must first understand what the characteristics of land tenure in mainland China are, characterised by the absence of private ownership of land. In essence, it is still based on two forms of ownership, established at the time of the formation of the Maoist state. The first is based on state property. Only the central government can dispose of it. The second is based on collective property. Local authorities can manage them within the areas under their control, the villages forming local bases of the statist pyramid whose summit is based in Beijing. In other words, land is no more commodified than it was in the days of Mao. Nobody can sell or buy it. On the other hand, depending on the extent of their respective powers, the authorities may authorize its use and distribution. In principle, unless authorised by the central government, the authorities in rural areas cannot expel farmers unless they, due to poverty, cannot develop the plots they lease them. However, with the accelerated expansion of market relations in the countryside, such poverty happens increasingly in huge proportions. In coastal villages like Wukan, in the past it was not so much the case, at least not to the same extent as today.

The extensive riots of 2011 broke out precisely because the mayor of Wukan, and his associates, with the aim of renting out the fertile and more or less valuable communal land to developers, tried to drive out the villagers, unleashing their particularly brutal militia against them. That’s why, in Wukan, as indeed in a lot of other villages in China, they brandished the banner of the fight against corruption as well as the red flag, a symbol of the collective ownership of land in their eyes – an illusion in my opinion – as their last line of defence. In 2011, given that the situation was becoming increasingly tense throughout the whole of Guangdong Province, the birthplace of “market socialism, and that the fierce resistance of Wukan was turning into a symbol, Beijing put pressure on Canton, the seat of the provincial government, to freeze land transactions, remove the mayor, to imprison and torture him, as well as members of his clan, in the special prison in the provincial capital reserved for corrupt local cadres, and to speed up the organization of municipal elections, scheduled by the 1987 law (!) which allowed those who had no party political affiliation to access municipal functions, including that of mayor. So it was Lin Zuluan, who had been appointed by the villagers to negotiate with Canton, presented by our democrats as “the leader of the revolt,” who ascended to the post and tried, from there, to domesticate the goat and the cabbage.

Today it is the same Lin Zuluan who is on trial for corruption in Canton and, of course, in the tradition of the Moscow trials and those of Beijing, has confessed to his “crimes.” I do not know to what extent he has “dipped his long chopsticks in the soup,” as the Cantonese put it. For those who know China and the mores of the members of the current “celestial bureaucracy”, from the bottom to the top of the pyramid, it would not be surprising. Anyway, the repression that strikes Wakun today is not contingent. The central government and all the bureaucrats involved in the provinces have decided to end the policy regarding concessions to those people they found difficult to deal with, who had tried to set up the previous team residing in the vicinity of the Forbidden City. As stated by the current Secretary General of the Party, during his inauguration speech on “market socialism”, there is certainly a “market”, but especially “socialism.” In other words, unrelenting coercion applied to all individuals who do not accept the yoke. Wukan was, somehow, the symbol of “local democracy” concomitant to the previous phase of “market socialism”. Which resulted, as elsewhere after a few years, in the ruin and accelerated impoverishment of hundreds of thousands of villagers. This led Lin Zuluan to sell communal land, already vacant or about to be, to developers, including those originating from Hong Kong, very close. It is against the resumption of such expropriations, where the role of the corruption of local officials from Wukan may have been negligible, that the villagers protested, more radically, at least in terms of form, because in terms of content the same limits, based on the defence of collective ownership and the red flag, quickly emerged. Sometimes associated with portraits of the Great Helmsman. In this sense, the mayor, Lin Zuluan, seemed to the villagers as the guarantor of the status quo. But the status quo is no longer a possibility for the state. The steamroller of “market socialism” is freewheeling ahead to crush the least resistance. Such is Beijing’s current objective. Wukan acted as a symbol of the earlier precarious compromise. So Wukan must be annihilated. We’ll see in the near future, in Wukan and elsewhere, if the wretched of the Earth in China can break with their own illusions and end the Chinese version of statist ideology which has been hampering them for generations.

Lao She (Old Snake), September 2016

PS: For further questions, please visit the site of “La Discordia” and its pages devoted to the discussion of revolts in China today, January 2016 (in French): Programme de décembre 2015/janvier 2016 et discussion “Des révoltes dans la Chine d’aujourd’hui” ( December 2015/January 2016 programme and discussion “Revolts in China today “)

[translation from the French by SF]

2:

Mainland China:

The emergence of massive radical opposition to nuclear power

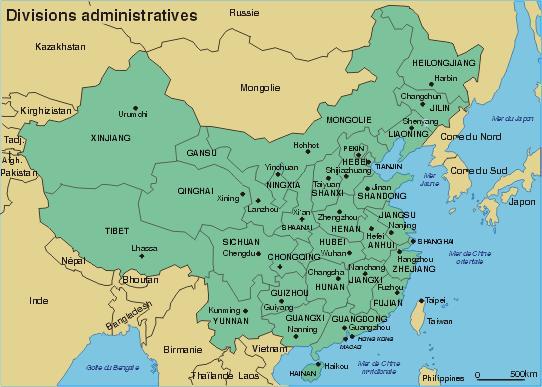

Dalian, in the province of Liaoning, third largest port in China, on the Korean Bay. In ten years, the region suffered two oil spills. In 2011, massive riots led Beijing to abandon the idea of installing the largest petrochemical plant in the country.

After hardly two decades, the devastating effects of the rapid industrialisation of China on the population’s health have been enormous, particularly those due to the proliferation of deadly petrochemical sites. These ravages are one of the causes of the revolts which increasingly upset the “harmony” of the country’s “market socialism”. To understand the meaning of these revolts, one must first understand that the key sectors of the economy, primarily nuclear, remain state property or the property of joint enterprises under the control of the state. Thus, the China National Nuclear Corporation (CNNC) essentially owns and manages the electro-nuclear power industry in China. This means that important decisions are made, in the final analysis, by the central government in Beijing – despite being the object of innumerable, more or less mafia-like, negotiations with local authorities, who don’t want to play the role of scapegoat in case of failure.

Up until recently, the petrochemical industry was the main target of opposition to the general poisoning caused by industrialisation. Massive and sometimes radical, this opposition has already led the state to suspend the implementation of construction projects intended for selected priority sites and has sought to install them elsewhere, which is not always possible. But from now on it’s the turn of nuclear power to be targeted. In 2012, the first warning shot was fired at Pengze on the Yangtze River in central China. It’s true that the building of the nuclear plant over the running water has been brought to a standstill since then for two different reasons: the concern of local residents, especially farmers, and the refusal of the provincial government of Jiangxi to bear the main burden of construction costs. But there is more. Since 2013, the realisation of two massive monumental projects as part of the State’s plans, which are as dangerous as the power stations, has been hampered by the insubordination of the potential victims of radiation. The first project concerns the preparation of the basis of nuclear fuel – enriched uranium; the second concerns the treatment and storage of nuclear materials created by the fission of uranium in reactors, starting with the highly valued plutonium. To the extent that the state intends to consolidate its position as a major world power in the nuclear field, military as well as civil, the realisation of such sites is crucial for the future of “market socialism”.

The sites preferred by the state, those likely to accommodate them, are primarily located in coastal provinces. Indeed, the nuclear power plants built or under construction in the near future are and will essentially be installed along China’s coastline, for reasons both strategic and geographic: the enormous need for water, the density of the rail network, etc. The first project dealing with nuclear fuel was to be built in Jiangmen, an integral part of the megalopolis of the delta of the Pearl River. It was steered by Beijing, in collaboration with the provincial authorities of Guangdong. Ever since the announcement of the selection of the site, in 2013, mass protests started up, accompanied by attempts at occupations of government buildings, clashes with police, sometimes involving the destruction and burning of official cars. As often happens in China, national flags were waved here and there On the other hand, , the slogans were not ambiguous: “Down with nuclear power”, “We want children, not atoms”, “We are already afraid to drink the water even without nuclear power,” etc. After some equivocation, the nucleocrats of the CNNC withdrew Jiangmen from the list of sites, claiming that “the maintenance of order and stability in Guangdong was a priority.”

“We want children, we do not want nuclear power.”

Jiangmen, in Guangdong Province. The first day of protest in 2013 against the project of a uranium enrichment plant.

The second project has just been reversed, during the summer of 2016 – the one concerning the processing and storage of fission material. Modelled on the plant at La Hague in France, the consortium formed by Areva and CNNC have committed themselves to realising it. The Town Hall council of the coastal city of Lianyungang, located in the Yellow Sea in Jiangsu province, was in the process of proposing the town’s candidacy to the consortium when the news filtered through. Which was enough to spark things off. It must be said that the region is already severely nuclearised. The reputation of the two reactors at the power station in Tianwan, thirty kilometers from the city center, is particularly appalling. In a few years, the site will include six additional reactors. Two are already under construction, making it one of the largest nuclear facilities in the world. That’s why this summer demonstrations, involving tens of thousands of residents of the prefecture of Lianyungang, have started – the demonstrations becoming increasingly violent since police killed two people. What’s more, sporadic strikes took place in the port area to protest against police brutality. Although, sometimes, the national anthem was sung, the slogans thrown up and adopted by the demonstrators left no doubt about their anger and determination. To cite the most repeated: “We love our Lianyungang – no nuclear dustbins!”, “Let’s protect ourselves from nuclear power!”, “Let’s protect the next generation “, ” Let’s not forget Fukushima ” and ” Don’t forget Tokaimura”. Tokaimura is the Japanese site for the preparation of nuclear fuel where, in 1999, uncontrolled chain reactions started, covering the surrounding areas with radiation. In short, for fear that the situation in the prefecture of Lianyungang would become explosive, the local authorities, with the backing of Beijing, decided to withdraw their application. But since then, they have been trying get dockworkers and other employees of enterprises dependent on the State, to sign papers in which they promise not to participate in activities or meetings hostile to nuclear power. Under the threat of losing their jobs. This shows that the previously mentioned hostility can’t bew reduced to the environmentalism which the new middle classes in China sometimes show, those who otherwise are more or less subservient to the Party.

Lianyungang in Jiangsu: a demonstration in August 2016, against the planned factory for the recycling and storage of uranium fission products. The slogan says: “Think of the future generations, refuse the construction of the plant for the treatment of hazardous nuclear waste.”

The revolt against the “lethal nuclear zones” has already gone beyond the limited framework defined by the members of environmental NGOs, who are often persecuted, beaten, kidnapped and imprisoned by the police. Yet their leaders, still tolerated in Hong Kong, claim they share the spirit of the laws enacted by Beijing against polluters. These laws seek only to sacrifice a few hated scapegoats accused of corruption. In the case of Jiangmen, these self-appointed leaders had advised the protesters to remain “peaceful” and not to “provoke” the Party. Following, in a sense, the Confucian precept that the meek shall, with the respect due to authority, present their petitions on their knees. But those who are primarily concerned have clearly decided to carry on regardless.

It is impossible to predict what will happen to such opposition, in terms of generalisation and further radicalisation. But they are a big threat to “market socialism”. Which the State has understood. And understood better than quite a few European marxist-type “revolutionaries” who, even when they stay in China, ignore or despise them, insofar as they go beyond their limited field of vision. They focus only on the struggles that they consider acceptable to them: the, certainly important strikes of the “mingong”, who for them symbolise the new “proletarian subject”, especially those concentrated in Guangdong’s barrack-like factories. Despite the fact that these “mingong”, who have settled for years in the province, have participated in the clashes in Jiangmen! But our ideologists show proof of their myopia in Europe when they’re confronted with similar things. So, in China …

■ Lao She (Old Snake)

October 2016

For all correspondance: lao.she@free.fr

3:

A few other links to articles about events in China this year (2016)

And this, from Its Going Down, is interesting: STRIKES ON THE YULONG RIVER: RURAL RESISTANCE TO CHINA’S CAPITALIST TRANSITION, though it reproduces, though merely in passing, as an aside not developed in the slightest, common historical myths about China, which are the subject of further critique by Lao She here (added 17/10/16):

Critical notes on ethnicity in China

Beyond the interesting information it provides on strikes in rural areas, this article about the district of Yangshuo, Guangxi, should, however, be subject to some clarifications. Because it implicitly accepts, in passing, the widely believed, hardly ever criticised, myth arising from the foundation of the Republican state in China, dating back to the 1911 revolution, attributed to Sun Yixian (Sun Yat-sen in Cantonese), and adopted by Mao Zedong. A myth that the basis of “Chinese civilization” has, for thousands of years, been driven by the Han, “the ultra-majority ethnic group,” surrounded by multitudes of “ethnic minorities”, to which the current state, in the “best case scenario”, confers local cultural and administrative autonomy. However, Jean-François Billeter, one of the few critical Sinologists today, like Simon Leys was in the past, said: “In the historical sources, which were almost all written by Confucian literati, ie by empire officials, the Chinese people appear not in their true diversity, but as a population subject to the emperor. This state was enough to define it. Revolutionaries, at the dawn of the twentieth century have transformed this administrative definition into an ethnic or racial definition. They needed a Han people as the foundation of their nationalism. The socialist system completed this idea by extending it to the national minorities. Ethnology could be of some service in the study of these “ethnic groups” because they were non-Han and “backward” but there was no question that it be used for studying the Han, a “revolutionary” people whose unity should never be the object of suspicion. That’s why researchers who nowadays go to the countryside sometimes feel like they’re discovering unknown continents.”– Jean-François Billeter, « Chine trois fois muette » (“China three times dumb”), Edition Allia, 2000. I recall that on Chinese identity cards, it indicated which “ethnic group” Chinese citizens are supposed to belong to. But there is no more an ethnic Chinese Han group than there is a Capetian ethnicity in France, a Tudor ethnicity in England, etc. The Han were there for over two thousand years, having succeeded the short-lived imperial dynasty, the Qin. The fame of the Han is because they consolidated and extended the centralizing statist process put in place by the Qin, in particular by crushing the great feudal families and not hesitating to place commoners throughout all the levels of the massive “celestial bureaucracy” being established. They even went on to nationalise the ground!

To return to Guangxi, I travelled there over twenty years ago, at the time when tourism was still limited. The reality of the local “unknown continent” was far removed from its official representation. The province, with 50 million inhabitants, has the status of an autonomous region – even its official name is the Autonomous Region of Guangxi Zhang. For although the Han officially constitute the “majority” (30 million), the Zhang constitute up to 15 million, the “majority” of the “minorities” in the province – the Yao, Dong, etc. Having moved around the region, I was, within the terms of specific local conditions, faced with customs, rituals, religions, more precisely with various pragmatic and more or less syncretic mixtures that did not match up with official classifications. I even met, not far from Yangshuo, a retired teacher who, to my question about his “ethnic” origin, had replied, like Woody Allen, “I am zhang when it suits me!” As with those Chinese who are more critical than the average, he did not believe in the founding myths of the national state, the creator of “market socialism “.

Lao She, October 2016

lao.she@free.fr

And the following are from the News of Opposition page:

8/8/16:

7/7/16:

China : Walmart workers launch wildcat strikes across China

3/7/16:

China, Lubu: government offices attacked as massive protest against plans for highly toxic incinerator hots up “…the Lubu town administration had suddenly halted plans for the construction. Residents expressed their anger believing the announcement to be temporary and a tactical move to diffuse unrest.”

25/6/16:

China: riot cops violently suppress demo against waste incinerator ” the riot police moved to clear the road, indiscriminately attacking the crowds with truncheons and fire hoses, according to locals. In a day-long battle that dragged on until about 11 p.m., the civilians responded by pelting the police with eggs and water bottles.”

21/4/16:

China, Zhejiang: heavy clashes with state over incinerator construction “More than 1,000 police officers deployed to the scene clashed with protesters, leaving scores injured or taken away after the most serious round of confrontations late Thursday…Despite the government announcing a halt to the incinerator project, some protesters carried on and broke through a police cordon and entered the county government premises, where police used water cannon, tear gas and pepper spray to disperse the crowd… Video clips and photographs posted online showed violent clashes between police and protesters, vandalized cars, and individual protesters with blood over their bodies and faces or with broken fingers.”…Daleks join China’s police force

14/3/16:

China, Heilongjiang: 1000s of unemployed miners clash with cops…more here…mainstream report on workers unrest … and another

8/2/16:

China, Hong Kong: fly pitchers resist state’s eviction policy – riots and clashes throughout the night

“During the clashes, police fired live gunshots into the air, wielded batons and hand-held water cannons and used pepper spray as protesters overturned and set alight rubbish bins and other debris, shattered car windows and threw stones at the police. …During the night, at least 24 people were arrested, while 44 policemen and members of the press were reportedly injured. It was not immediately known how many protesters were injured. As traffic started to resume in the early hours of Tuesday morning, many crossroads remained blocked by police and protesters cordons, and some fires continued burning unabated.” Video here: https://nz.travel.yahoo.com/video/watch/30773621/riot-police-protesters-clash-over-hong-kong-street-vendors/

More video: http://edition.cnn.com/2016/02/08/asia/hong-kong-riots-shots-fired/ (video)

10/1/16:

China: strikes and protests in China for 2015 double that of 2014…Hangzhou: state organises an innovative method of securing safe train journeys

And anyone disagreeing with the official reason for this will be subject to re-education classes [SF]

6/1/16:

Leave a Reply