“Mandela can go to hell!”

– the mother of a guy killed by the ANC’s cops on a demo, whilst Mandela was president.

“The great appear great because we are on our knees”

– Jim Larkin

A 95 year old multimillionaire dies peacefully and the ruling world treats him as an endearing demi-god because he spent 28% of his life in prison under a vile fascistic form of government and on his release became an international political star. Did the world’s most well-known shitheads turn up for the 34 killed at Marikana, who never even had the option of the misery of prison? Do people even know their names? Have they heard of Teboho Mkhonza, Michael Makhabane, Marcel King and all the others killed by the ANC cops in peaceful demonstrations before Marikana? No – because these unknowns never had any mystical aura fabricated for them that could possibly wash off on the powerful scum hoping to bathe in Mandela’s reflected glory.

Vitriolic? Sure! How else should one express oneself against such a sickeningly insidious manipulation? “Reasonable” genteel tones incite fuck-all.

In the melting pot that is South Africa, when things came to the boil and then the people stopped stirring, the scum rose to the top. The story of Mandela’s rise to Sainthood is the story of the revolution that stopped.

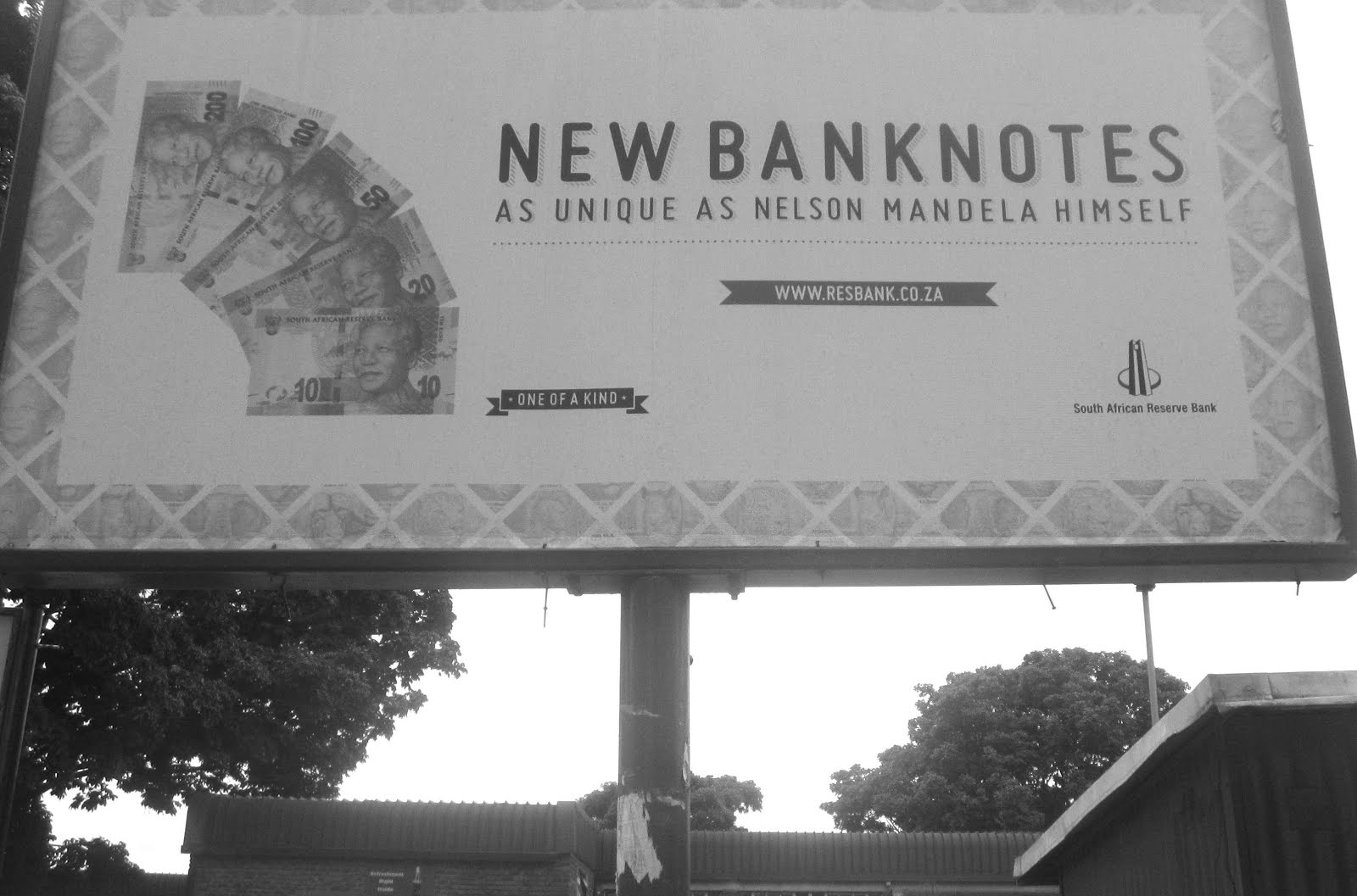

The function of the circus put on now for the funeral of Mandela in South Africa by the world’s dominant powers is to try to implant in the spectators’ heads the idea that capitalism can reform itself, can make progress, through “reconciliation” of formerly antagonistic forces. It is designed, once again, to reconcile the poor to those who keep them poor, smothering them in some transcendent fog where the only thing visible is Mandela’s smile whose charm is meant to induce amnesia about any significant contradiction. Judgement of people on the basis purely of their personality is generally a flight from looking beneath the surface, , which would entail a judgement on their relation to class society.. Whilst the intensified commodification of everything and the constant reinforcement of state power and the market economy everywhere creates ever-worsening disasters both on the ecological level and in the everyday lives of the vast majority behind the scenes, on stage the show must go on. We are everywhere encouraged to forget history in order to gaze admiringly on “the giant of history”, the man who, apparently, ended apartheid and improved the lot of millions of blacks. “History” is for the “Great”, not for nothings like you and me. The truth of the past and present of South Africa and elsewhere is photoshopped out of the picture. But in the real world, as a recent Oxfam report said, South Africa is “the most unequal country on earth and significantly more unequal than at the end of apartheid”. [ see also this – link added 18/12/13]

“ By sitting around a table and talking about these things with the whites brings no good future to us. It’s just like talking to a stone. Now by violence they will understand a little of what we say – a little. Now by war they will understand everything – by war.”

– young South African black quoted in the film “Call It Sleep” (script here)

After sitting round a table with de Klerk (a man who had been an integral part of the brutal apartheid regime since 1978) Mandela’s first gift to the rulers was to call for discipline, an end to looting and an end to the theft and burning of cars and an end to classroom boycotts. That is, an end to the subversion of exchange value and an end to the subversion of “education” – i.e. ideological conditioning aimed at acceptance of relations of domination and submission. Back to work, back to school. Back to wage slavery and back to brainwashing. Whilst the war cry of the uprising in 1976 had been “The school for the oppressed is a revolution”, the peace cry of the new rulers was “The school for the oppressed must be subordination”. The call for “discipline” here clearly meant a call to accept the discipline of the commodity economy with a bit of a change of those who run it, “peace and reconciliation” to your miserable lot. After 15 years of the advances and retreats of a genuine revolution already having a global influence, the vast majority accepted the “no good future” brought to them courtesy of St. Nelson, giving up practical struggle for the carrot of a better tomorrow through a change in the personnel of the state. A road that led straight to Marikana. So nowadays in any potential future uprising it would be better to say, “ By sitting around a table and talking about these things with the ruling world, black or white, in the electoral charade or on the telly, brings no good future to us. It’s just like talking to a stone. Now by violence they will understand a little of what we say – a little. Now by war they will understand everything – by war.”

As everyone with a bit of knowledge about the situation knows, the idea that apartheid no longer exists is yet another myth. See this, for instance, from almost 8 years ago:

“ Heritage Park is enclosed by a computer-monitored fence that zaps intruders with 35,000 volts and alerts a corps of security guards…. Heritage Park, at 200 hectares (494 acres) slightly bigger than Monaco, is resolutely middle class. Of 1,500 residents, 1,495 are white. Beyond the fence are three townships, home to tens of thousands of poor black people and coloureds, the term given to those of mixed race. It is a brutal juxtaposition: inside the fence, pastel-coloured two-storey homes in Cape Dutch, English Tudor or Tuscan styles, neatly divided into seven suburbs with names like Beaulieu, Cape Heritage and Tuscana Close. Walk outside the wire and within metres you are in a sea of tin shacks and low-cost government-built houses.” – from here.

And if you think this had nothing to do with the Mandela when he was locked up in prison, that he changed when power got to his head, then this quote of Mandela’s from the mid-80s should disabuse you of such illusions: “We want Johannesburg to remain the beautiful and thriving city that it is now. Therefore, we are willing to maintain separate living until there are enough new employment opportunities and new homes to allow blacks to move into Johannesburg with dignity.” New homes for the ANC and their lackeys, new employing opportunities for the small number of rich black middle class, but for the rest – very few nicely worded “employment opportunities” (ie an opportunity to get a bit more money being shafted than being “redundant”) and no social security – certainly not like during apartheid, when the whites desperately tried to buy off the revolutionary movement with increases in benefits and massive wage rises. Which poverty, of course, lacks “dignity” and the sensitive souls of the rich want their beautiful thriving environment to remain untainted by such unsightly sights.

The fact that this Christian funeral of the Modern Christ is attended by both the rich mass murderers of this world (Barack Obama, Tony Blair, George W. Bush, Hilary Clinton, John Major, Francois Hollande, etc.) as well as those at the sharp end is indicative of how Christianity means different things to different people depending on their position in the hierarchy. “Give unto Caesar that which is Caesar’s” is what the rich Christians promote, but the poor Christians, relegated to the back row, forget “It is easier for a camel to pass through the eye of a needle than for a rich man to enter the kingdom of heaven” when mourning the death of this multimillionaire. But of course, probably many adoring Jesus Mandela will express, sometimes even a little publicly, their contempt for the living fat cats at this funeral. The other day, at the memorial service, the crowd booed Zuma – but, ever-contradictory, remained respectfully admiring of millionaire President Barack Obomber (whose drones, may I remind you, just killed 15 people on their way to a wedding in the Yemen). This is the essence of the Christian mentality – it provides the vast majority with an internal moral sense of self-justification on the basis that they, at least, are not fat cats, that they are not patent scumbags, whilst remaining passive towards those who are and the society they maintain, and even wanting to believe that there is good in some of them, that, contrary to all honestly reflected experience, the system can be made good by a change in the personnel of those at the top.

“Turn the other cheek….Love your enemy” said Christ. “Mandela taught us to forgive”, say the spectators. Forgive and forget – the sermon of those who want history to be repeated: the chant of those who want the rulers to be forgiven will invariably want to become like them, as Mandela did. You can only really forgive and “move on” when the material conditions, the miserable social relations, have moved on – when the world and life has been changed fundamentally. The Mandela Show from his release from prison onwards aimed to give the impression that things had changed – but only in the standard sense (from “The Leopard”) of “For things to remain the same, everything must change“.

It’s no coincidence that this almost overwhelming show – the world’s biggest funeral ever – is taking place during an epoch when, once again, proletarians are expressing their anger everywhere. The global show of unity in false memory of the dead – aimed at distracting from the real struggle for life by the living. The spectacle is, as ever, the rulers’ most insidious stun grenade, making everyone see stars as they fall into unconsciousness. Mandela is constantly evoked by the world’s rulers as a model for correct forms of “opposition” as much as by some of the world’s ruled. “What cannot be done, as Mandela has taught us, is to sow hatred. Oppositions are a sign of democracy, but you should not stir up, nor exploit the anger and discontent or fuel dangerous feelings,” said an Italian politician about the wildcat strike and independent social movement spreading across Italy this week (see here). But for the masses of individuals attacked by the brutal power of the economy, by its ideologies, cops and armies, to evoke Mandela means repressing such feelings and repressing the acts that develop from them, which truly are dangerous to the hierarchical social relations embodied in bourgeois democracy.

When Mandela is evoked by the poor, it’s usually as support for some illusion of pacifist civil disobedience attributed to him (even though some of the ANC bombs during the 80s killed innocent bystanders). For example, this. Because the spectators remain above all external to history, they feel the need, particularly when the conflicts of present society have hit them directly, for their gestures of “opposition” to be embodied in mythological heroes, like St. Nelson, who represent history for them. Christ used to be essential to the Christian mentality because he is the subjective incarnation connecting Earth with heaven; he is the external being who makes the Christian mentality possible because it is the Earth that constitutes for Christianity the actual inaccessible heaven. The function of “the meek shall inherit the Earth” mentality for social relations on the Earth is to repress the recognition that the gates of heaven can only be stormed by furiously storming the Winter Palaces of the rich and powerful, and at the same time storming the palaces of richness and power that each individual potentially possesses. But for the ordinary submissive mentality “revolutionary” heroes like Mandela literally perform the function of Christ, and you don’t need to be a Christian to have a Christian mentality, to be hypnotised by the forces relentlessly promoting such an icon. The romantic vision of a “Giant of History” carries out, through the sacred person of the hero, the union of terrestrial triviality with the heaven of universal history. Zuma said, “Our nation has lost its greatest son. Our people have lost a father.” Only the Holy Ghost remains, haunting the living. And anyone who says “Mandela can go to hell” is a blaspheming heretic who should be burnt at the stake.

“Hanging on the walls of the house I had pictures of Roosevelt, Churchill, Stalin, Gandhi … I explained to the boys who each of the men was, and what he stood for.” (Long Walk to Freedom p240). In this autobiography Mandela declared that he “…had always been a Christian” (p620). It’s not in any way contradictory that this Christian used to have a picture of Stalin on his wall. Christians generally try to emulate or imitate Christ, just as Leftists evoke some other icon or other. The Bolsheviks were great pioneers in this type of cultifying: Lenin declared that to really be a Marxist one should always ask oneself, “What would Marx have thought and done in this situation?” Today one can find people protesting against this and that ignorantly using the image of Mandela to substitute for their own words and ideas. It’s no coincidence that the current global spectacle, with its tendency to pick up ideas and practices from, and unify, all previous forms of hierarchical power, particularly those developing capital accumulation, should today find itself united in its eulogy to a former Stalinist-turned-neoliberal. Christ, Roosevelt, Churchill, Stalin, Gandhi, Mandela – the need for “radical” heroes tears us away from our own rebellious initiatives, and ends up crushing and co-opting every independent initiative. The need for rebel role models, for external authorities in pretensions to changing the world, imbued in some glow of perfection (though the content varies between the different forms necessary for each geographical place and epoch) is based on the maintenance of the utter nothingness of the lives of the admirers. Such an emptiness expresses the brutal powerlessness imposed by the self-same system they fail to set their minds and bodies against, the system that erects and resurrects the need for heroes and saints, particularly ones that are integral to the system, as Christ, Roosevelt, Churchill, Stalin, Gandhi and Mandela, all in their different ways, most clearly were.

The mythical history of Mandela is a grandiose version of one that everyone is meant to somehow identify with: a long struggle, heavy repression, endurance in the face of persecution, release, realisation, and a happy old age surrounded by admirers, dying satisfied with the feeling that one has made a significant mark on the world. How we all would like to feel that! Pushed to the margins of existence, most of us enter old age with a feeling that our lives have been meaningless. Of course, loads of people have fought and been killed, or fought and been locked up, remaining unknown. So the political hero is created by the capitalist show to provide a vicarious substitute meaning. Above all, to provide those who are constantly crapped on from above and excluded from any direct power to have the deluded consolation that within this shithouse of a world not all those who occupy the thrones of power are bastards.

The reality of Mandela’s politics is a little different – I suggest those wishing to struggle against this world of lies read at least the first part of my introduction to a critical history of the social movements in South Africa, which I wrote almost 9 years ago. And for those who want some insights into the current situation, I suggest they read these passionately expressed pieces called, “Another man done gone” & “Post-marikana notes”.

– Sam Fanto Samotnaf, 13/12/13

**************

The following was written by Siddiq Khan of Love Letters Journal, just a few days ago:

Let us not mourn famous men

(formerly entitiled “Test Taste”)

Mandela is dead. Good riddance. Unfortunately the democratic lie is as healthy as ever. In 1994 blacks in this country were satisfied with electing a black president; if they were not, they would not have allowed him and his cronies to order an end to mass struggle – or to turn it off and on, like a tap – when it suited them. Twenty years later, the taps are broken. We are not satisfied anymore. More elections are around the corner, and we will be ordered again to voice our dissatisfaction at the voting booth with the old motto: don’t change life, change leaders.

The majority see through the con: most don’t bother to vote. The fact that so many people find such an apparently significant act not worth the trouble of standing in line for a few minutes (or hours) once every five years is indication enough of the level of disaffection felt by people towards the putrid corruption at the heart of this ridiculous charade. To us, ‘free and fair’ elections = ‘Free-from-relevance and fairly-useless’. We are disgusted not at ‘electoral fraud’ but at the fraud of elections. Despite the renewal of autonomous contestation at the point of production; most of this despair (and anger, as shown by ever-present protests) over the failure of politricks to change our condition of daily misery has thus-far been contained within the terrain of politics itself. What is necessary, however, is to direct this discontent towards its source – the miseries experienced in everyday life.

Often the route to this kind of radical simplification turns out to be complicated: To approach everyday life; it is necessary to return for a moment to Tata Madiba. He is a hero. There is perhaps nothing more to say about him. Like every other hero, celebrity, and star in this upside-down society (including those of the ‘progressive’, ‘radical’ and ‘revolutionary’ variety); Mandela has always been an enemy of ordinary proletarians. Next year there will be national elections; the politicians will use his image as a red flag, waving it around like bull-fighters to trick the working class into running this way, running that way — only to butcher us in the end (see: Cato Crest & Marikana). “The emancipation of the proletariat is the task of proletarians themselves”. An essential element of this task is learning to say: Fuck politics, political parties and politicians. Fuck the ANC, fuck all the fake-opposition parties, fuck the president, fuck parliament, fuck Desmond Tutu, and especially fuck Nelson Mandela. Unless we can tell them all to go to hell, they will do everything in their power to take us into its deepest recesses. As a matter of fact we already are there; and it’s the job of Mandela and all those like him to keep us here. Many mortals have had visions of “that abode of the damned which the justice of an offended God has called into existence for the eternal punishment of sinners”. Dante Alighieri, the inventor of the Italian language, was one of them. But, as a poet once said, “Visions are problems. Vision is the solution that precedes the problem.” To put it another way:

It was the earth that Dante trod

When he trod Hell, it was the earth:

Itself sufficient for the hearth

That warms the hands of a cold God.

We don’t need visions or visionaries, heroes or heroism. They are all part of the problem. What we need is clarity. A clear view of the problem. Then we can begin to experiment with solutions for ourselves. Everything about this society trains us to keep our eyes turned to the sky: “you’ll get pie there when you die.” This way we are unable to look at the un-heroic existence right in front of our noses. “The most powerful weapon in the hands of the oppressor is the mind of the oppressed.” We see visions, we follow dreams, we fight for phantoms. We fear ‘sin’, we pursue careers, we struggle for ‘democracy’. And every day, life passes us by because – unnoticed, unthought of, and unspoken – everyday life passes us by.

“But to use a somewhat simplistic spatial image,” wrote Guy Debord in Perspectives for Conscious Changes in Everyday Life – which, to modern ears, sounds like a self-help manual, and in a sense it is, but a radical one, “we still have to place everyday life at the center of everything. Every project begins from it and every accomplishment returns to it to acquire its real significance. Everyday life is the measure of all things: of the (non)fulfilment of human relations; of the use of lived time; of artistic experimentation; and of revolutionary politics.”

The English say “the proof of the pudding is in the eating.” Which means: “if capitalism were good, the lives of those who live in it would be good.” Our lives are not good. They have not been good. We know they will not be good as long as we have to work, so long as we have to make money, so long as we have to live in a world of jobs, couples, schools, prisons, armies, marriage, police, bank-accounts, gangster-governments, anarchism, democracy, socialism, NGOs, religion, family, The Mail and Guardian, shopping.

Of all these evils, work is the worst curse that ever struck mankind. When our ancestors lived off the land, when they hunted and farmed for themselves, they did just that: they lived. They laboured and they played, they struggled and they toiled – it was not always easy to make a living, but at least what they made, poor as it may have been in many respects, was life. The moment they started to work, labour stopped being used to make life. It is now used, as the bosses put it, to ‘make a killing’. When we enter our workplaces we leave our lives behind. We do the making, we do the killing; it is our lives that are killed. When it is done to make money, labour is murder. When it is done to make love, to make life – when a woman goes into labour – or to nurture life in child-rearing, housework, and re-creation; labour is not work. It makes no money. It means nothing, because it kills nothing. In the vile world of work & workers there is no meaning, no value, no use outside ‘the autonomous movement of non-life’ whose slick gears are greased by blood and fuelled with corpses. To be a worker is to be a slave. Many poorer workers are ashamed of their poverty. It is not the relative poverty of some but the absolute slavery of all workers that is truly shameful.

All of us – worker or unemployed, home-maker or student, suburbanite or bergie – are forced each day to live in ways that are out of our control. Until now we have failed at every opportunity for freedom because we never attacked this curse of work in a simple, straightforward enough way. We have confused ourselves with a mishmash of jumbled ideas about the economy, social-justice, the government, social-services, elections, social-democracy, growth-rates, grass-roots participation, self-management – we’ve tried every way to change our lives except the one way that will work: to get rid of work. There is nothing unusual about such a goal. For the majority of human existence on this earth, not a single person worked. For thousands of years women across Africa would call their neighbours to help them farm their fields, and nobody thought of turning it into a ‘decent job’ or demanding ‘a living wage’. They shared homemade beer, cider and wine; they sang and they danced in graceful, elaborate costumes; they smoked tobacco and dagga out of painstakingly carved, beautifully assembled pipes; they ate together with food freely provided by the host; the children played among themselves or snuck off, as they always do, to quench the passions of the heart in one another’s bodies. Even with all the digging, weeding, harvesting and planting, it was actually an excuse for a party. [Samotnaf note: whilst this may be true for South Africa and lots of other places, it’s not true for everywhere by any means; often conditions were very harsh and life was short and unpleasant.]

Today it is work rather than field-parties that organises social time and space; the only parties of any significance these days are political ones. Every Party, even when it calls itself revolutionary, promises to put us back to work. Whenever we walk out on the job, sure enough all the unions will call for a return to work. The problem with the worker’s movement is that it’s not an anti-worker’s movement. The only solution to the unemployment crisis is full unemployment. The proof is in the pudding; the truth is in the tasting. Now that the old parties and unions have so thoroughly discredited themselves, and more people are coming together to change their own lives, many choices will be faced which will determine whether the fate of our generation escapes the miserable failures of our parents. Many people will spring up with proposals for this or that imaginary system and requests for support of such and such a cause. From now on, whenever there is need to test if a course of action actually holds the possibility for moving us closer to liberation, the first thing to ask is ‘will this be a practical step towards the abolition of work?’ If not, not.

It’s never so simple, of course. Often the answer will be, ‘possibly’. Then the question is ‘how’ – and ‘how likely’? Another is, ‘what next’? Another is ‘what else?’ And so on.

Still, the first principle remains… primary.

If not, not.

Siddiq Khan,

7 December 2013

Leave a Reply