This is a recent translation (mainly by JR) from French of a text written by a guy with ex-Yugoslav family connections (he was born there and his parents came from different parts of the former country, though he’s lived in France for a very long time) who recently returned from Bosnia and wrote this about the recent events there. The title is mine. I’ve added a couple of photos to the text and some relevant bits and pieces mainly at the end (on Kosovo, the Tuzla proclamation and a separate text on the plenums).

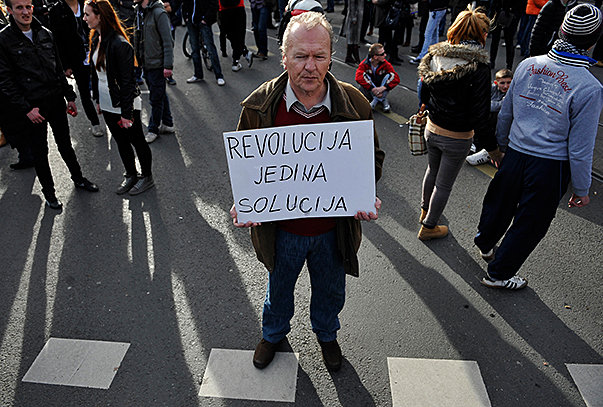

“Revolution – the only solution”

Bosnia

Part One:

Back from Bosnia

I had planned, on returning from Bosnia-Herzegovina, to write a more complete, in-depth text on all of the various aspects of what I witnessed or thought. But once back, I was faced with the choice of either giving some useful keys to understanding the recent events or the more laborious option of writing, for mere intellectual satisfaction, a more polished product. Fortunately, my hesitation was resolved by the sound proletarian principle that work is the worker’s first enemy. The prospect of production without productivity – which will abolish the economy we hate – brought me around to realizing that the actual usefulness of an activity is worth more than its abstract merit. The account that follows may then, if useful, have a sequel; for now, I don’t want to entrap myself in an activity I find difficult, that of a writer.

Long live revolution Down with work

I still think, though, that many interesting issues raised by these events should be developed further, on a practical level as well, and the more collectively the better.

The breakup of the Yugoslav State is inseparable from the social resistance, in Europe and elsewhere, against the restructuring that brought the post-war boom to an end and reached a peak of violence in the late 1970s/early 1980s. The same “liberal wave” that crushed the British workers’ struggles during the era known as the miners’ strike spread across Europe in the form of massive layoffs, plant closures and the elimination of entire industries. That wave was to have repercussions stretching all the way across Europe to decisively impact the breakup of Yugoslavia.

The existence of Bosnia-Herzegovina as we know it today, an artificially rigidified political construction, stems directly from the defeat of social struggles in Europe during the 1980s, as restructuring swept through the global economy. More specifically, it was shaped by the breakup of Yugoslavia, which inevitably gave rise to the present multiethnic hodgepodge. This whole issue was aptly summed up by a guy at the Mostar plenum, who reacted to a previous speaker’s enthusiastic words about the country’s multi-ethnic base by saying, “Who cares about your multiethnic stuff; before the war we didn’t know who was what, and we were all the better for it.”

A player in the global political arena, the Yugoslav economy grew steadily until the 1970s, while the country’s reliance on loans advanced by the international monetary system kept its internal socioeconomic structure under tight control.

The first signs of its dependence became evident in the 1980s, with the obligation to comply with new international exigencies introduced in the form of economic and social policies. Attempts to enforce acceptance of those exigencies triggered fierce social resistance in every single part of ex-Yugoslavia[*], as a continuous movement of determined struggles from 1985 to 1992 (and then on into the war) in opposition to the bureaucracy which controlled the country and carried out the IMF-mandated reforms in its own bourgeois interests.

It was against that background that the spreading social struggles in Yugoslavia demonstrated the State’s inability to continue playing its role as a State, i.e. to extract from its proletariat a sufficiently high return on the capital invested in the Yugoslav State. Yugoslav proletarian resistance was countered by organizing and supporting nationalist reactions and ethnic fragmentation, which during the war served to impose social peace. The determining factor in this solution, linked to the historical context, was the collapse of the Soviet Union, which paved the way for western capitalists to sweep up Eastern European markets and for German reunification to redefine the contours of the European project.

Twenty years and 100,000 deaths later, the proletarians of Bosnia are beginning to strike back, as a succession of social rebellions shake every part of ex-Yugoslavia. The struggles that exploded in Bosnia this winter may signal a re-awakening of the movements of resistance crushed by nationalisms and the war in a changing and unstable international environment.

It seems useful to recall that the eruption of resistance in ex-Yugoslavia, evidence of the “prematurely” exhausted State structures which had previously relied on nationalistic strategies to maintain social peace, has immediate bearing on the resurgence of struggles in Bosnia. Not that those strategies were magically overcome, but rather that their ability to pit the divided populations against each other by attributing one side’s misery to the opposing population’s national interests had disintegrated and become unworkable in the new European environment. Although visible in certain situations, this “ethnic” aspect – not of dividing the struggles but of keeping them from exploding – has lost momentum and is fading, even though it survives like a field of scars buried more or less deeply, depending on the regional situation. At the same time, a kind of “Yugoslavism” has re-emerged, and as such is an implicit critique of the crushing weight of nationalism. It is a new and now more concrete vehicle for neo-Titoist illusions of an idealized eastern version of the post-war social compromise, materialized as a broad welfare system, more extensive than in the West, which guarantees a minimum income, housing, healthcare, and free access to education. In that idyllic image of the period prior to the national divisions, “the State was, unlike the present, capable of successfully fulfilling its role.” Still hidden in the shadows of social memory, the current “Yugoslavization” of social discontent entails overcoming not only the nationalistic divisions of the past twenty years but the situation in the ex-Yugoslav federation, where each bureaucracy separately organized the social repression of its republic’s population to achieve the same aims of division. The speed with which the news of the Bosnian revolt spread and the swift reactions of solidarity, from Skopje to Zagreb, would have been inconceivable under the Titoist media and police system.

The arrogance with which the IMF reforms have been carried out over the past twenty years, first by a bureaucracy converted to liberalism and later by new generations of businessmen that largely took their place, only radicalized the desperate population’s perception of politicians and new local capitalists as Mafias. The alternately nationalistic and social democratic discourse that those “Mafias” wielded so skillfully did much to erode their ideological veneer.

Nevertheless, the discourse that dominates the protest movement in the region plays up the demand for a State conceived as “a good organization of society,” which would magically pull apolitical politicians and honest businessmen out of its hat – an ideal State, in short, which does its job well under its population’s control. This does not, however, mean that such demands should be judged by classifying them in categories solely on the basis of appearances. Social reality does not exist in a vacuum, but develops in the course of the movement. Its contradictions on the one hand, manifested in all their brutality, and on the other, the proletariat’s lucid recognition of their “no future” situation leave little room today for party politics to produce lasting alternatives. This is reflected in the progressive weakening of the political framework of governance imposed on the ex-Yugoslav territory some twenty years ago. As was the case twenty-five years ago, the limits of these situations are also determined by the international framework in which they develop.

The proletarian nature of the struggles pitting the dispossessed, faced with severe difficulties of subsistence, against the organization of the State and the economy is a permanent feature of social frictions both in Bosnia-Herzegovina and in the neighboring regions. This has, to a certain extent, fostered analogous conditions of struggle not only within the new borders but in all territories where struggles had developed before the war.

Democracy, whether real or participatory, is a recurring theme. The fixation with democracy, which often has a local focus, is primarily directed against the ineptitude of solutions devised in the faraway, lofty spheres of policy-making. An anti-party, anti-politician and anti-privatization discourse diffuses throughout social protests. In the case of Bosnia-Herzegovina, the protests are marked generally by anti-nationalism and by anti-fascism, although the latter has a different meaning in the mouths of bureaucrats in the Bosnian Serb Republic or in that of people in Herzegovina. The past also affects the nature of the antifascism in a region where, during the war, Croatian nationalist militias (backed by certain governments) openly proclaimed their adherence to Nazism (but not fascism, linked historically by the Croatian far right to Italy, which stripped Croatia of part of its coast).

Before going into other aspects of the protests, I will describe the “popular assembly,” or “plenum” as it was called in Tuzla, which in various forms swept across an enraged Bosnia-Herzegovina. The functioning of the plenum in Sarajevo highlights some of the contradictory oscillations at play in this new democracy:

On February 17, before climbing to the floor where the plenum was held, I was stopped in the lobby by cops (real ones in uniform) in charge of the assembly’s security. I had to walk through a metal detector and put my bag through another one. My water bottle was opened to check that I wasn’t trying to sneak in alcohol or gasoline (?).

The meeting room, accessed from the first floor, was an immense amphitheater with a large circular corridor above the central area lined with seats and small tables. One to three cops, very relaxed and not exactly friendly but almost, ambled here and there to make sure no one would disturb democracy. A few amongst that bunch of uniforms, visibly more attentive than the others, behaved more like intelligence agents than traffic cops.

Discussions and speeches flowed in easy succession. The concern with reaching a consensus did not prevent firm criticisms from being voiced. The atmosphere was cozy, suggesting that one was among decent people.

By my estimate, 600 to less than 1000 people took part in the plenum, more than at the rally held earlier in the street, no doubt because some came after work.

To sum up the main point on the agenda, “Although no one can represent the plenum, we have to choose who will physically present our grievances/demands to the authorities. Thirteen volunteers have come forward, we agreed beforehand (?) on a delegation of seven people, so that it wouldn’t be too big… Now we need to decide who will go and who won’t… The thirteen volunteer citizens will introduce themselves to you one by one.” (The word “gradanin”, derived from “grad”, town or village, may be translated as citizen but equally as bourgeois, an unintentional way of putting democracy in its proper place.)

The thirteen volunteers introduced themselves quite simply: first and last name, occupation and a couple of remarks. Most were unemployed, a few workers with jobs, some pensioners, two migrant workers who’d returned to Bosnia, one from Sweden and the other from France. As I recall, there were three women. (Many women were present in the plenum and, indeed, more generally.)

Once the introductions were finished, the woman who had the mike asked the “citizens” to come forward one by one so that the assembly could reach a decision about each of them. The first two were booed straight off, then the others were approved or rejected according to a somewhat haphazard, erratic procedure which was nonetheless always very democratic. For each of them, though not in any very specific order, the question put to the assembly was “Do you want this one or not?”. Those rejected were always, it seems to me, put through several rounds of questions before the decision was reached. Some of the volunteers, recognized by the assembly, were cheered and elected right away. By the end of the session, which lasted quite a while, the choice settled on seven people. At that point one of them took the mike from the woman who was moderating the discussion and said, “Listen, as far as I’m concerned, I was chosen, so I’m not speaking to try and change the decision about myself, but why don’t we all go?” Mad applause. The woman reclaimed the mike and put the proposal to a vote. The assembly decided that all the volunteers would be part of the delegation. During the entire process of rejecting or approving citizen-delegates, one section of the assembly seemed to me to carry relatively more weight in the decision-making – a cluster of likely participants in the criminal depredations of public property which left certain official buildings blackened by smoke… until the day they disappear altogether.

We will return to that question later. Interestingly, unlike Tuzla, here the assembly did not raise the issue of freeing the protestors who had been apprehended. How many they were was uncertain, and there seems to have been no follow-up on the issue. This is all the more disturbing in that there were references to police raids of people’s homes during or after the events of February 7th in the newspapers and in discussions I had, but without any details.

These are some of the practical aspects of the plenum. Although it cannot as such constitute a real counter-power, in its allergic reaction to the idea of politics it puts itself in a position as a possible force to improve the latter.

For an assessment of the more general situation, however, it should be assumed that substantial variations exist locally.

The events in Bosnia are not only affected by the broader international context but interconnected with the impoverishment and resistance prevailing in the various parts of ex-Yugoslavia. The whole area shares highly similar perceptions and socioeconomic conditions that are linked to the previous waves of struggle now re-emerging from collective amnesia. This is reflected in the spontaneous expressions of support that have poured in from all corners of ex-Yugoslavia since early February or in the frequent references to the situation twenty years ago, before the national divisions. (A recently-published pamphlet[†] on current resistance movements in Portugal discusses the issue of the memory of struggle. The same recovery process seems to be present in the struggles in ex-Yugoslavia, which are fueled by the resurgence of current and past experiences.) However long the path may be and whatever the discourse, these social movements help overcome the borders hewn with an axe to divide them.

To better grasp events in Bosnia and the situation more generally, it is worth mentioning an ongoing struggle in Serbia at a railroad car factory. The report dates from February 10th, coinciding with the Bosnian conflagration.

The 250 workers at a rolling-stock manufacturing plant went on strike and blocked the railway line at Kraljevo.

Back in April 1987, when 400 workers were on the company’s payroll, they launched a determined strike over their shrinking wages due to the plummeting value of the dinar. Their action was part of a widespread outbreak of increasingly radical struggles demanding that the company managements be sacked for not raising their real wages (following which the bureaucracy and its trade unions, both denounced by the workers, put forward nationalist arguments, with funding from their Western backers, to convince the workers that they should blame the population of the other republic for having monopolized the fruit of their efforts).

According to currently available information on the struggle, the back pay they are owed totals one year of wages, they haven’t been paid anything since their last strike eight months ago, they are blocking a rail junction and have set up a strike committee, implying that they’ve gotten rid of the trade unions. Insofar as the blockage apparently prevents vehicles produced at the Fiat factory from moving through, the position they occupy is strategic for freight transport. So far, the Serbian government seems unable to forcibly throw them out, and in fact the Finance Ministry met with the strike committee representative to propose payment of a month’s wages immediately and, a month later, payment of an equivalent amount. The workers rejected the offer and demanded full payment of back wages as well as the reinstatement of their benefits (which I understand depends on the issuance of pay slips). The company management quit, or was fired, but this did not in any way weaken the strike committee’s determination to continue blocking the railroad line.

A number of similar movements are under way in Serbia right now, but it is hard to know whether the worker occupations for payment of back wages are actually strikes or occur in companies that have gone bankrupt (more or less arranged in the wake of privatization, as witnessed on various occasions in Bosnia).

Movements of the same type are increasingly widespread in other Eastern European countries (and elsewhere).

Having gone into some of the reasons for the declining influence of the nationalist framework in the social realities of ex-Yugoslavia, another important point should be raised in this connection.

From the start, the complex cultural cohabitations within a small territory like Bosnia-Herzegovina left no possibility for delimiting the territorial boundaries of each of those realities, which were initially all the more absurd because the personal references to those identities were not just complex but relative. The Western option to break up Yugoslavia and recognize the resulting nation-states, each under the sway of a particular nationalism, was especially complicated to implement in Bosnia-Herzegovina. Nevertheless, to complete the breakup of Yugoslavia, it had to be done. Before this patchwork of States could gain political recognition, it was necessary to delimit territories each with its own ethnicized power, hence the hodgepodge result. Ethnic cleansing, as it is called, is a direct outcome of the implementation of that plan. The three national entities that had to be defined were the Croats, the Serbs and the “Muslims”, now known as the Bosniaks. The Croatian and Serbian nationalisms relied militarily on the resources of Croatia and Serbia, respectively, and ideologically on their patriotic national discourse and on the historical references resuscitated for the occasion. The “Muslim” area and its national discourse were invented, without any historical references, over a period of a few years, between 1992 and 1995. As a result, right from the start, patriotic national discourse was less well assimilated in the Bosnian area. While not an explanation, this needs to be factored in to understand how the latest revolt spread in Bosnia where, with the exception of Mostar, the most determined forms erupted in the Bosnian area of Bosnia-Herzegovina. Indeed, the uprising in the “Croatian” area didn’t go beyond Mostar, which overlaps the Bosnian area. As for the “Serbian” zone, there were troubles and protests in Banja Luka (and perhaps elsewhere) but not to the same extent.

Part Two:

The lovely month of February

Introduction

As early as February 5th, a trade-union activist whose name I lost had the following hallucination: “May everyone in all towns and cities and in all districts rise up and fight!” Lucky man, who at the very moment he had his intuition completely forgot to stick to his trade-union agenda!

February 5, 2014 could arguably be considered the date marking the beginning of a social conflagration which, with a little patience, could well have a promising future. Rather than making forecasts, the point is to try and grasp the possible implications of an event that concluded the defeat of the most important struggles against restructuring in the 1980s. With the present resurgence in what was formerly Yugoslavia, the point is to understand how these social struggles relate to the situation rooted in their past defeats, which subjected them to new States, which were reduced to local, more malleable underlings servile to the IMF’s successive instructions.

This situation shows concretely how the divisions created by the national borders put in place in the early 1990s to crush all social resistance to the “new world order” have been rejected socially. By recapturing the experience of past defeats, the struggles surging in Bosnia-Herzegovina have produced echoes beyond the borders whose national divisions had stifled them. The movement is a step forward, but it will only have a future in the struggles it sets in motion and to the extent that it becomes a moment in their emergence.

In defiance of the national divisions that served to crush resistance in the early 1990s, the present social resurgence openly and immediately rejects nationalism and asserts solidarity throughout former Yugoslavia, which has supposedly disappeared, according to the official line widely accepted in the West, rejected as a bygone oppression. It is not unusual in Bosnia-Herzegovina to hear talk of a “Bosnian spring”.

During its half a dozen years of perseverance, until the early 1990s, the proletarians of Yugoslavia remained utterly “anti-historical.” They never realized, in the situation at the time, that their workers’ struggles of another era, aimed at defending their rights to remain exploited as before, were doomed to failure. (Their resistance to the deterioration of their situation, then as now, determined their mobilization.) They fought until they drained the State of its raison d’être – to make them work within the system imposed by the new norms of exploitation.

This victory, won in the midst of general proletarian defeat, lacking any prospect for expansion and reducing the class to the mere reproduction of its own alienation, handed it over to its worst enemies by means of national reconstructions and their promises of a better future. Subjected to the twin influences of nationalism and terror, they let themselves be recruited by their respective armies, which armed them with weapons to defend themselves, their families and their friends, and to fire on yesterday’s friends. C’est la guerre!

The revolt that flared up in Bosnia-Herzegovina is a confrontation with that history, which had to be liquidated before proletarian solidarity could be rebuilt step-by-step, twenty years and countless hardships later. The enemies this time, more fearsome than liberal businessmen and corrupt politicians, are the new illusions – either democratic or smacking of neo-Titoism – fabricated to subject the proletariat once again to the very constraints that have doomed them to their appalling situation and kept them there. The crux of the battle to come is that no State can exist without the social relationships that make the proletariat the producer of the world that beats it down.

You need bread to make history.

The situation in Bosnia-Herzegovina mirrors that in ex-Yugoslavia and, more broadly, the social conditions in much of Eastern Europe: rampant unemployment, increasingly costly access to basic needs (food, health, housing), a social dead end resented all the more because getting schooling or a higher education is so difficult. Arrogant social practices: scandalous wages, routinely late or unpaid wages. Privatizations imposed by economic normalization go hand-in-hand with liquidations of industrial operations as dictated by the international market. The plant and equipment bought for next to nothing in the privatization process are commonly plundered and then sold for a profit or reassembled at another site some place in the world where they can be put to a momentarily more lucrative use. A great number of struggles are connected to this broader economic reality all over the globe, which is inaptly characterized as corruption. Such “misconduct” in fact reflects the very nature of a social relationship, not its aberrations. Nonetheless, workers deprived overnight of their means of subsistence may reasonably perceive it as such. Moreover, to cut costs, the consequences of the company liquidations are not mitigated by any social measures. Those consequences are all the more severe because the material impoverishment of the affected population limits the potential for social solidarity.

A large proportion of the struggles reported in newspapers or that we hear about revolve around the plundering of resources, which the victimized populations do not see as part of the economy’s normal operation and is often attributed to the “abusiveness” of economic laws rather than to the nature of those laws itself.

This in no way prevents such struggles from aiming directly at the bourgeoisie’s immediate interests and attacking its ability to fulfill its functions.

Brief Chronology

A few opening remarks on the Dayton accords are useful in giving an approximate idea of the institutional clarity of Bosnia-Herzegovina’s makeup. The country is a Confederation consisting of, on the one hand, the Bosnian Serb Republic with its capital in Banja Luka and, on the other, the Muslim-Croat Federation. The latter comprises Croat Herzegovina (a region distinct from Bosnia) with its capital in Mostar and, beginning at Mostar on the other bank of the Neretva River, Muslim (Bosniak) Bosnia, whose capital, Sarajevo, is also that of the Confederation. In addition, unlike the Croats of Herzegovina, the Serbs of Bosnia and the Bosniaks[‡] are Bosnians, i.e. populations of Bosnia. Simple, isn’t it? It is worth stressing that apart from those three groups, there is no institutional recognition of anyone not belonging, or not wishing to belong, to one of these identities, as is the case of Romas, Jews (in ex-Yugoslavia, they comprised the second largest Jewish population after those of Vojvodina) and several other minorities, although I don’t know how many of them remain.

February 5, 2014

Aggressive modern economic methods and the social pressures of unemployment directly contributed to the events that unfolded following the protests on February 5th. Side by side were poor workers or those waiting for payment of their back wages, strikers occupying companies after management made off with the money, a lot of unemployed workers and some students whose only prospect was unemployment, as well as the entire younger generation, very visibly present on the front lines, and very angry.

For years, nothing had changed in the population’s disastrous situation and everything was going well for the administrators of the Dayton accords and the beneficiaries of the economic reforms liberalizing the exploitation of regional resources, which of course included the workforce. On that day, demonstrations were held in Zenica, Bihac, Prijedor, Sarajevo (2,000 protestors), and Tuzla (6,000 protestors). Something bigger was brewing, which would take twenty-four hours to erupt.

Samotnaf note

The text misses out the following events from this day:

“Officials say 22 people, including more than a dozen police officers, were injured and 24 arrested when protesters in the northern Bosnian town of Tuzla clashed with police over the closure of local factories.

The clashes on February 5 began when some 600 people tried to break into a regional administration headquarters.

The protesters — who police said were joined by local soccer fans — threw stones at police and set tires on fire.” (from here)

“Around 600 people tried to storm the building of the Tuzla local government, accusing authorities of turning a blind eye to the collapse of a number of state firms after their privatisation.

Protesters joined by local football fans stoned the windows of the building and set tires on fire, blocking traffic in the city centre, a police spokesman said. Police eventually forced them back and cordoned off the building.

Eleven vehicles, most of them belonging to the police and government, were damaged, police spokesman Izudin Saric said.” (from here)

February 6

One of the rallies took place in Mostar, a key location during the revolt as the only city among all of those set ablaze that extends into a non-Bosniak (previously called “Muslim”) area. It gathered in the Croat area, where the center of the modern city is located. The protestors lit fires in the streets and stood around them discussing and shouting slogans. There were no confrontations that day.

The anger at that point concentrated in Tuzla, in what remains of the formerly industrial city. The protestors’ slogans denounced unemployment, the wheeling and dealing behind the privatizations, unpaid wages, plant closures.

It seems the cops attempted to intervene but ended up losing the day. Very violent clashes left 130 wounded, 100 of them on the cops’ side.

February 7. The reawakening of the Balkans!

In Banja Luka, Bosnian Serb Republic, another rally was held around the same issues that were raising tensions throughout the region: unemployment, crooked privatizations, corrupt politicians.

In Tuzla, Zenica, Sarajevo and Mostar, the main cities of Bosnia (formerly designated Muslim), the parliaments and government buildings were torched all on the same day, and fury erupted spontaneously all across the territory, electrifying the entire region and beyond.

In Mostar, which is significantly the only city in eruption straddling the Croat and Muslim areas, after the government buildings were burned, the headquarters of both the Croatian nationalist party HDZ and the nationalist Muslim party SDA were set on fire. Interestingly, graffiti signed by the “Red Army,” a group of “antifascist” fans of the local soccer team, covered one of the official buildings subjected to the flames of fiery critique.

February 8

Breakout of protests across Bosnia.

No confrontations were reported for that day in Sanski Most, Konjic, Sarajevo or Mostar.

In Bihac, the rally ended with a clash between two to three thousand protestors and the police.

500 unemployed and laid-off workers demonstrated in Bugojno in solidarity with Tuzla and to demand the release of all arrested protestors.

Suad Zeljkovic, head of the Sarajevo district administration, resigned.

In less than 24 hours, the news spread beyond the borders:

In Serbia, Croatia and Macedonia (and the following day in Montenegro), plans were made to organize rallies over the coming days in solidarity with the enraged workers of Bosnia-Herzegovina.

1st Plenum (name given to the assemblies) in Tuzla called for “citizens” to discuss the situation and work out their demands.

During the night, arrests were made in near Tuzla, apparently in the anarchist and “far-left” circles.

February 9

The daily rallies spread throughout BiH (Bosnia-Herzegovina).

Protest in Velika Kladusa. The recurring themes were 20 years of lies, Government of thieves. (The “20 years” refers to the lapse of time between the outbreak of the war and the creation of the States run by nationalist parties that had promised to solve the social problems through national “liberation.”) There as elsewhere, the rallies put forward plans to be imposed on the government. In Velika Kladusa, these involved limiting elected officials’ salaries, doing away with their “special” benefits, supervising or exposing privatizations, etc.

February 10

In Belgrade, a crowd of 300 demonstrated in support of “brave Bosnia-Herzegovina”.

Protest in Kalesija. On a banner:

Bosses = slave drivers

Workers = slaves

February 11

Demo in a dozen cities in BiH ( Bosnia-Herzegovina)

Sarajevo: Striking Holiday Inn workers and urban transit workers were present with their signs among the protestors in the demonstration.

February 12

1st solidarity rally in Zagreb (Croatia)

An anarchist banner: Long live the struggle of the working class.

Sarajevo. Occupation of the Holiday Inn by its employees, who hadn’t been paid for two months. The hotel, built for the Sarajevo Olympic Games, was privatized in 2003 and then sold to the Austrian Alpha Baumanagement for 22.8 million Euros. The workers accused the company of labor regulations violations, with the government’s complicity, and of noncompliance with the provisions of the privatization settlement.

Heads-up from Hungary over the overall situation in Eastern Europe: workers in the chemical industry occupied their factory and demonstrated in Budapest against its owners for refusing to pay their back wages.

February 13

1st Plenum in Mostar (capital of Herzegovina, encompassing a Croat-Bosniak area on the two sides of the Neretva river).

200 people gathered in the meeting room beneath a banner declaring “Liberty is our nation”.

Demands put forward: removal of the BiH government, no more financing of political parties.

Skopje (Macedonia). March to the Bosnia-Herzegovinian Embassy in support of BiH, “against nationalism, nepotism and corruption,” a slogan reflecting exactly the perception of the local situation, as generally across ex-Yugoslavia.

Zagreb (Croatia). A thousand people marched from the flower market to the square of the victims of fascism. Banners reading: No war between peoples, no peace between classes. One class, one fight.

Vranje (Serbia). Workers at the Jumko holding company without pay for the last seven months. 1500 protestors blocked the Belgrade/Skopje highway.

Kraljevo (Serbia). Demonstration by striking workers whose company had not paid their wages since May 2013.

February 14

Bihac. 220 workers at Bira Bihac demonstrated in front of the factory. They hadn’t been paid since November 2013. They were joined by workers from the Robot factory.

Zavidovic. 5000 demonstrators – unemployed workers, disabled ex-soldiers, civilian war victims and their families, pensioners, workers at Krivaje and other companies – demanded the resignation of the SDA mayor (Muslim nationalist) and the whole municipal government and proposed that the assembly appoint an unaffiliated manager until the next elections. Some of the protestors planned an occupation of the square, with a tent city, until the municipal government resigned. Rioting broke out on February 7th. The mobilization was massive (for such a small town) and went on until at least February 17th.

February 15

Podgorica (Montenegro)

In response to a call for: Revolution in Montenegro

Everyone in the streets

Tomorrow the Parliament

various local groups, anarchists, “ultra-left”, etc. organized a rally in support of the workers of Bosnia-Herzegovina. Chants by the crowd were punctuated in the background by cries of “thieves, thieves” directed against the politicians. The overriding sentiment was strongly anti-nationalist. On the far side of the crowd was a fire-blackened building but I don’t know the story behind that.

An elderly protestor commented, “Our children, the workers’ children, have not become hooligans (referring to Bosnia’s arsonists).Whatever they burned is nothing compared to what those vultures have destroyed.”

At the end of the demonstration, there were clashes with the police and stone throwing, after which 20 protestors were arrested.

Belgrade (Serbia)

Solidarity rally with the “heroes of Bosnia-Herzegovina.”

Signs:

Today Tuzla, tomorrow Belgrade

Heroic Bosnia we are with you

A kiss for worker’s Bosnia-Herzegovina

The nationalists are the capitalists’ lackeys

We are all hooligans

BiH hooligan, I love you

During the rally, the cops intervened when a group arrived bearing Serbian flags with the royal insignia distinctive of the Chetnik far right (recalling the Serbian royalist resistance liquidated during World War II by the “Croat” Tito’s communist resistance, aided by Churchill for political reasons). For a while they shouted the names of Karadjic (mostly) and Mladic.

In Futog (Vojvodina-Serbia)

Workers at Milan Vidak, who had been fighting against the company’s closure since January 21st, occupied the factory. (a struggle seemingly of much the same kind as we see in France.)

Osijek (Slavonia – Croatia)

Solidarity rally with the workers of Bosnia-Herzegovina. (Osijek is in the part of Slavonia that was occupied and bombarded by the Yugoslav army starting in the summer of 1991, before the war entered its second phase in Bosnia-Herzegovina in 1992. It was in this Croatian city that the politico-military situation led to a shift in the workers’ struggle in 1991, directly from striking to fighting in the war.)

February 16 (Sunday)

Mostar.

Spanski trg (Spanish Square). 250 protestors.

A huge banner:

Bosniaks, Herzegovinians

Don’t you realize that Romas, Jews and others live here

A curse on the constituent peoples!*

Together, unity of all citizens for prosperity and solidarity

Thank you Zagreb / Skopje / Belgrade

Also there was the banner hung at the front of the Plenum meeting room:

Liberty is our nation.

*The constituent peoples are, to the exclusion of all others, the three “constitutive nations” of Bosnia-Herzegovina, i.e. Bosnia, Croatia and Serbia.

February 17

Leskovac (Serbia).

Workers at Interleminda decided on an all-out strike and occupation of the factory. They blocked the main Belgrade–Vlasotince highway the same day.

The plant owners owed them 1 million Euros in back wages.

February 18

Skopje (Macedonia).

Several hundred unemployed, along with two groups, Lenka (Social Justice) and Solidarnost, demonstrated in front of the offices of a trade union (?) to condemn union collaboration with the political class. Unemployment is 30% for the country overall and 62% in the northeast.

February 20

Demo in Banja Luka (Bosnian Serb Republic). More than 1000 protestors against the social situation. Rally supported by veterans of the Republika Srbska army.

Demo in Bihac 100 protestors

February 25

Mostar. The association of civilian victims of the war joined the Mostar Plenum.

Croatia. Civil service strike over nonpayment of salaries of more than 70,000 employees.

Union-controlled industrial action by railroad, urban transit and healthcare workers.

February 26

Mostar: 20th consecutive day of protests.

Tuzla. 1000 demonstrators.

Zagreb (Croatia). Trade-union demonstration against the gutting of labor laws. The new legislation provides for possible extension of the workweek to 56 hours, facilitates layoffs and limits the right to strike.

Banner:

The plundering of Croatia began with the war in 1991…

So ends, at least for now, a somewhat disorganized account which nevertheless should help in understanding the situation.

ljutacorba@voila.fr

[*] See “De la grève à la guerre (1984-1992) : la situation en Yougoslavie face aux restructurations économiques des années 80,” a text not yet translated into English on the vast movement of worker struggles during that period.

[†] available at: http://echangesmouvemen.canalblog.com/archives/2014/01/09/28906377.html

[‡] Formerly, the term Bosniak designated an inhabitant of Bosnia. Today it is used to refer to the “Muslim” population.

Samotnaf Notes

1.

This text misses out events in Kosovo (also part of ex-Yugoslavia), perhaps because they were mainly student riots, weren’t directly linked to the events in Bosnia and weren’t as significant as these events. Moreover, the war in Kosovo (1999) happened sometime after the wars in the other parts of ex-Yugoslavia and involved NATO, so perhaps it’s a separate case in some ways. However, it seems worthwhile including these reports:

“Hundreds of students from the University of Prishtina marched from the Student Centre in Pristina towards Rector’s office, where they joined the rest of the protesters mainly from civil society….

A large number of students are blocking the rectors office in protest demanding the dismissal of the rector .. . The rectorate staff have continued working today to protect police forces reports Kosovo Police

Students of the University of Pristina are trying to enter the Rector of UP, while Kosovo police and Rectorate security are trying to stop the entry of the students in the Rector’s office. Students are staying already sitting inside the courtyard of the Rector surrounded by large numbers of the Kosovo police including the special unit.” (from here) (Feb. 3rd)

“Police in Kosovo used pepper spray and batons to disperse hundreds of students demanding the resignation of the head of Pristina’s state university on Thursday over reports their professors had forged academic works.

At least five police officers were injured when students threw rocks as they tried to enter the university building, a police spokeswoman said. Dozens of students also received medical treatment.

A flurry of reports in the Kosovo media have accused professors at the university of publishing works in fake online journals in order to further their academic credentials.” (from here) (6th Feb.)

“71 people, 31 of whom police officers have been injured during the protest staged in front of the Pristina University in Kosovo on Friday, the local police announced.

Police spokesperson, Brahim Sadrija, said that for the first time the protesters attacked the police and started throwing different hard objects at the law-enforcement officers.” (from here) (7th Feb.)

“Kosovo’s top most senior university official has resigned from his post following days of clashes between police and protesters who accused him and other staff of faking their teaching credentials.

Ibrahim Gashi made the announcement yesterday on Kosovo’s public broadcaster, RTK.

He blamed the events on Kosovo’s political opposition parties. Mr Gashi’s appointment was backed by the ruling coalition.

For over a week demonstrators, mostly students, said university president Mr Gashi and dozens of staff published research in dubious journals abroad.

Police in riot gear clashes with protesters outside Mr Gashi’s offices in the capital Pristina. Dozens of police and protesters were injured” (from here) (8th Feb).

2.

In mid-February, I wrote this on the proclamation from Tuzla:

About this declaration:

This is a rather sad example of positive political manoeuvres, in my opinion; it’s got lots of people desperately hopeful, but there’s nothing here that looks like much more than a standard form of recuperation, hoping to freeze the momentum of the movement and channel it into a bureaucratic programme. Whilst clearly expressive of an attempt to break with the past, it still sees things in terms of representative government. There’s an element of a utopian capitalist project here, unrealisable within any international capitalist framework. And worse – a “‘pragmatic government’ made out of professional, non-partisan and uncorrupted members”. Sounds like some proletarianised “pragmatic” middle class professional-cum-budding-politicans-of-the-people have prepared this proclamation beforehand. As if historical experience hasn’t shown us that even those who up until their entry into positions of state were not obviously compromised within the existing system, have still clearly gone on to develop the logic of their hierarchical position and consolidated it. Any “professional” political position inevitably leads to a self-interest separate from the general interest, whilst still needing to represent this general interest. And what’s this – “:Maintaining public order in cooperation with citizens, police and civil protection , to avoid any criminalization , politicization and manipulation of any protests .” ? Ambiguous at best. What order? What police? What “citizens”? “Civil protection ” of what? Of course, there could be a radical interpretation of this, but also a very conservative one. Despite graffiti like “Stop nationalism” (in Tuzla) and ” All of them must go- Fuck Nationalism.” (Sarajevo), this seems like an attempt to channel the movement into a purely national solution which, for the working class, is not only an impossible “solution” but also what the representatives of international capital undoubtedly hope for.

Titoism also developed some form of self-management within a state capitalist framework with a bit of private enterprise. The regional heirarchy of financial favours and poverty, was a divide and rule strategy to contain the massive class war there before the EU-provoked civil war massacres. It was a way of pitting region against region in order for the central state to appear to be the sole arbiter of peace which posed as the resolution of conflicts that the central state had itself encouraged. Which was one of the things it had in common with the Ottoman Empire before it, when it maintained; “a precarious equipoise of mutual animosity” between the different regions, as my O level history textbook put it. For some of the contradictions of the period from the end of WWl to the Titoist period, see Yugoslavery.

Maybe, considering the overwhelming disaster neoliberalism has been, there’s a kind of “inevitability” to this social democratic-cum-statist solution in reaction to neoliberalism. But historical experience has told us that the “inevitable” frying pan-fire false choice uncriticised and approved without attempting to go way beyond this “inevitability” “inevitably” leads to just as bad or worse. There’s no doubt that the most tragic aspects of history are those that are not-self-organised, those that resign themselves to an external authority. It is the fundamental tragic mistake that history and our own consciousness never forgive. Such tragedies repeat themselves, but the second time usually as an even worse tragedy – and no farce.

It might well be that history will repeat itself if people in different parts of the Balkans don’t explicitly oppose the attempts to manipulate, once again, the different regions against each other: Glas Srpske, the most widely circulated daily newspaper in Bosnia – Herzogovina, has even led with a cover story, claiming that protesters in the Federation were being armed and prepared for sorties into the Serb-dominated entity (see last paragraph here). Which is intended to once again turn the working class of the region against each other.

Whilst positive political “solutions” tend to be imposed as abstract ideals onto the fluidity of the movement, it might well help the current situation to take a critical look at the history of workers’ councils, with their system of permanently revocable mandated delegates. But this would have to be connected with taking over public buildings, work places etc. This is already happening a bit – but the content of these sit-ins (see, for exampole this) seems to be focussed purely on preventing asset-stripping; as far as I can see from this long distance, they’re not so far discussing how to connect internationally with people fighting their misery, or accompanying their sit-in with actions directly organising the distribution of food and other necessities. Though, of course, given the lies about what’s happened in each region, simply finding out the truth of the last 30 years would be an extraordinary leap.

3.

On the plenums, it’s worth looking at this article:

“There is something truly perfidious in the media that found it appropriate to interview intellectuals and cultural workers about the citizens’ plenums, even while a thousand of those citizens — in Sarajevo alone! — showed up and could have been interviewed at such plenums — they who used up their “adrenalin” to express just how much this system had humiliated them, denied them basic rights, made them bitter and brought them to the very edge of existence. Because, you see, had they interviewed them, they would have had to show the very thing that was nowhere to be found in yesterday’s news — namely, the deeply class-based nature of this rebellion, the sheer hunger and bitterness of these citizens who came not only for the “collective therapy” as Jeličić would have it, but in order to transform some of that anger, sadness, and despair into some action for a better tomorrow. Maybe then the media would also have to show the rather uncomfortable and unrefined expressions of the people who do not have any distance from the anger and social unrest that transformed into violence last week, the distance that highly educated cultural workers and professors whose opinions I was reading last night could have.

In other words, while that past Friday I could hear and read something about the socio-economic problems of workers, students, the unemployed, about the corruption of the entire government system in this state, about the kleptocratic privatization that was enacted over the backs of precisely those workers in Tuzla who brought out all of Bosnia onto the streets — tonight, I couldn’t find any of it. The violence that happened just a week ago was already well past us, there only in so far as we were all distancing ourselves from it, having forgotten, of course, that such violence is only a reaction to the kind of violence perpetrated by this state for over 20 years. And what is more important, that as soon as the violence stopped, so have the government step downs.

Today, we’re all talking about the plenums, but without any context or any idea what these people are doing there and what brought them into that gathering to begin with or what they are planning as their next step. To make matters worse, no one is questioning the causes or the consequences of this entire rebellion, but rather, most are reflecting on the psychological or the intellectual effects of the gathering itself. Well, damn it, it seems that the buildings of the cantonal governments went up in flames because they wouldn’t let us have plenums earlier!

This is also why, I guess, it didn’t occur to anyone to connect what was happening at the plenum in Sarajevo with today’s strike of all 140 workers of the Holiday hotel; that is, to show how these plenums were set up exactly for the purpose of organizing a more constructive type of rebellion than the spontaneous one that had engulfed all of Bosnia last week, and with such organization, bring about basic changes in this society so that it would no longer be possible for hotel owners to hold 140 workers as slaves for months! It also didn’t occur to anyone to connect the Mostar plenum with the shameful and cowardly attack on Josip Milić, the president of the Union of independent Labor Unions of the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina. While fascists with baseball bats understand quite well who, why, and in what way is responsible for the rebellion, such a lesson escapes the Bosnian media. The same is in Tuzla, where you can find dozens of statements by professor Damir Arsenijveć, before you will hear just one interview with the workers of Dita or with some other everyday victims of this system.

What is a plenum and what is its purpose?

Catharsis is important, to literature professors as much as to those who are living the tragedy of “transition” in Bosnia today. OK, let that be one of the functions of the plenum. But the way the media have served up the plenums, it seems like they are a pure idyll of some liberal understanding of democracy, in which, you see, the people came to lead themselves out of trouble, on some magical path akin to the one Alice in Wonderland takes. Except, it’s unclear which way or by what means one should go on such a path.

What is lost in all of that is that a plenum is first and foremost a meeting of citizens, not for the purpose of the meeting itself, but explicitly for some other purpose. These people at plenums were not there to supplement representative democracy, nor were they there to fruitlessly complain – the latter is a sport so well developed in Sarajevo cafés that people don’t need an excuse to engage in it. Those thousand people who showed up tonight at the Youth Hall in Sarajevo came to plan out their next move: the torch had been lit in Tuzla Friday a week ago; people have been on the streets for 8 days straight; but now that spontaneity has to be organized into a program, into some plan by which they would reach the demands that were read out tonight.

Demands are one thing; the path to their realization something different. And that is precisely the purpose of the plenum: to organize that same crowd on the streets, but what is more important, to find a way to organize the 93% (in the Federation) or 88% (in Bosnia/Herzegovina as a whole) of citizens that support this rebellion privately but are still waiting on the sidelines, fearful or unconvinced that this could possibly work. To organize them to join the protests and a movement that will create some other system that should be more just than the one we have now. But that new system will not fall down from the sky at one of the plenums; rather, the small army that has gathered at the plenums will organize it in the streets and squares of the cities, at workplaces and unions, at universities and high schools, and in the final analysis, in the homes and lives of those silent 88% of Bosnia’s citizens.

Despite positively referencing Cabral, and some other leftisms (eg the implication that one can organise other people, when it’s a question of creating situations which encourage their self-organisation), it’s still very interesting.

[*] See “De la grève à la guerre (1984-1992) : la situation en Yougoslavie face aux restructurations économiques des années 80,” a text not yet translated into English on the vast movement of worker struggles during that period.

[†] Formerly, the term Bosniak designated an inhabitant of Bosnia. Today it is used to refer to the “Muslim” population.