“The school for the oppressed is a revolution!”

“The school for the oppressed is a revolution!”

– Soweto pamphlet, 1976

June 16th 1976, the school students of Soweto rose up, initially against the obligatory learning of the rulers’ language (Afrikaans) in schools. What they initiated was one of the world’s greatest revolutionary movements, spreading throughout South Africa and way beyond a revolt of schoolchildren. And yet fairly little is known about it – as compared with, say, the Russian Revolution or France in May 1968. Here, I hope to begin to redress the imbalance.

The following is taken from 2 texts – “White man – we want to talk to you” by a white liberal journalist called Denis Herbstein. This has been put here because of the facts that it contains, not because of some of his silly reflections (e.g. his description of migrant workers: “twenty men are housed in a bleak dormitory, devoid of privacy, family warmth and lasting friendships — a prey to all manner of social and psychological evils that were uncommon in traditional society — broken marriages, homosexuality, prostitution, venereal disease, alcoholism.”). And Selby Semela’s first-hand account of what happened (co-authored with Sam Thompson & Norman Abraham), taken from “Reflections on the black consciousness movement and the South African revolution” (the first section, “The 1976/77 Insurrection”)

I have reproduced most of the content of 2 chapters from the Herbstein book, chapter 1 (Soweto — the First Four Days) and chapter 6 (the year of the schoolchildren), though I emphasise that these are extracts, not the complete chapters.

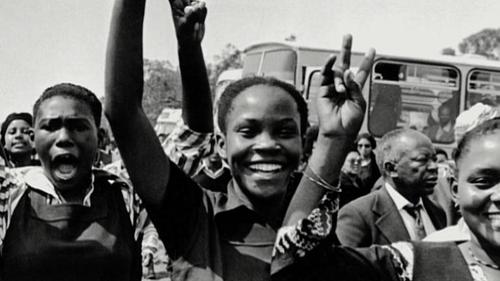

Wednesday 16 June 1976 is a cold winter’s morning in Soweto a South African township of a million, perhaps a million and a half, blacks. Teenage boys and girls, neatly dressed in school uniform, file out of their matchbox houses to join their schoolmates in the dusty streets. It is not yet seven, but their parents have long since left to begin their working day in the homes and factories of white Johannesburg. The students are whistling, singing, chanting, greeting friends with the clenched-fist salute of black brotherhood, shouting ‘Amandla Awethu’, ‘Power to the People’. Cardboard placards proclaim ‘Afrikaans is oppressors’ language’ and ‘Asingeni’ (We won’t go in). They merge into one of several streams —- from Orlando, Meadowlands, Dube, Naledi — the elite of young African boys a girls who have managed, against all odds, to reach secondary school.

But today they are not going to their classrooms. Their destination is the Orlando football stadium, where they will hold a mass meeting to protest against the enforced use of Afrikaans as a medium of instruction for mathematics and social studies. They move from school to school, calling on those who are already inside to come out and join them. One stream is heading first for the Orlando West junior secondary school in Phefeni, where the 500 pupils have refused to attend classes since the middle of May. Another six schools in Soweto have been ordered by a white circuit inspector, Thys de Beer, to use Afrikaans.

Tension has been running high in Soweto for several months culminating in an incident the week before, when a white security police lieutenant was trapped by angry schoolchildren at Naledi High as he questioned a pupil about a ‘subversive’ pamphlet. The lieutenant’s car was burnt out and he had to be rescued by police reinforcements armed with tear-gas. Most of the marchers today are at schools where English is the sole medium of instruction, but they fear that they will be next on de Beer’s list.

As the classrooms of one school empty, an irate black headmaster telephones the police. A member of the South African Students’ Movement, organizers of the protest, appeals to his ‘brothers and sisters’ to keep calm. ‘Don’t taunt the police; don’t do anything to them. We are not fighting.’ At police headquarters, Brigadier Schalk le Roux, divisional commissioner in charge of Soweto’s racially-mixed police force, is surprised to hear from his chief security officer that a big march is taking place. Despite the incidents at several Bantu schools, he does not think that the situation is explosive. He sends ‘a Bantu to the school to find out about the demonstration’.* But Bantu policemen are not welcome. ‘Go and stay with your Europeans in town,’ the students tell him.

Near Jabulani police station, a white man, thought to be a plain-clothes policeman, fires a shot at two students who are carrying a placard: ‘50—50 Afrikaans and 50-50 Zulu for Vorster’. A mile away, the largest group, numbering I0,000, but still growing, climbs up Vilikazi Street to the Orlando West school. They are excited, euphoric almost, at the success of their enterprise.

But now, screaming tyres and the revving of motor engines announce the arrival of ten van-loads of police reinforcements. There are nine whites among them, armed with revolvers, semi-automatic rifles and tear-gas. The show of strength, far from cowing the students, fuels their excitement. They taunt the police, wave their placards defianfly. They sing the national anthem of the black people: ‘Morena Boloka Sechaba sa Heso’ (God bless our nation). The officer in charge, Colonel Jobannes Kleingeld, does not have a loud hailer, and so cannot call on the students to disperse. Without warning, one of his men throws a tear-gas canister into the crowd, which retreats and, angry now, regroups.

More canisters are thrown, but the pupils hold their ground. Stones drop among the police. Colonel Kleingeld takes out his revolver and fires one shot into the crowd. Hector Petersen, thirteen years old and black, becomes the first recognized martyr of Soweto. No order is given, but the white policemen begin to fire repeatedly. Some students attack the police with stones, while others tend the dead and wounded. A seven-year-old boy is taken to a clinic, but he is dead on arrival. Colonel Kleingeld shoots an ‘adult ringleader’, Hastings Ndlovu, when, he claims, his life is in danger. By now Kleingeld is using his Sten gun because, he says, ‘it has a more demoralizing effect than a pistol shot.’ The students scatter into side streets, as still more police arrive.

Reports of the shootings spread rapidly through the township. The students surge up into Beverly Hills, past Uncle Tom’s Hall, through the dried-up bed of the Klipspruit stream, breaking into groups, calling for recruits, bumping into children playing in the sand, shouting out the news to old ladies on their stoeps, overturning and burning cars, and hunting especially for the white Volkswagens used by officials of the Bantu Affairs Department (BAD). They attack anything or anybody who is of the Government; and if he talks Afrikaans so much the worse, for this is the language on the lips of the white policeman on a dawn raid — ‘ Waar’s jou pas?’ (Where’s your pass?) — or in the court which sends a man to gaol for not having a pass, or which expels him to a distant ‘homeland’. But most of all, it is the language of the Government which framed the hated laws of apartheid.

A white W R A B (West Rand Administration Board) official is stabbed in many places, and left bleeding to death at the side of the road, draped in a poster with the words scrawled in blue ink: ‘Beware! Afrikaans is the most dangerous drug for our future’. A black policeman is pulled from his van, his hands are locked together with his own handcuffs, and he is beaten.

Others are luckier. A British immigrant, Mrs Sylvia Carruthers, pleads from her surrounded car: ‘I’m English.’ She is allowed to go.

The area around Uncle Tom’s Hall, not half a mile from Orlando police station, is like a war-zone. The students set up a road block, and question all who wish to pass. A driver, apparently white, is dragged from his car and beaten up, but his life is spared when the students realize that he is Chinese. Enraged groups of boys and girls attack, burn, loot, anything that has the stamp of white, and particularly of Government, domination: beer halls, bottle stores, post offices, administration buildings, the golf club house, even schools and libraries. Bakers’ vans are stopped and the black drivers allowed to escape, but the bread is distributed to the people and the vans set alight. When the police arrive, the students protect themselves with a dustbin lid in one hand and throw stones with the other. At Orlando High School, the Eton College of black South Africa, the words ‘Victory is certain — Orlando M P LA’ are sprayed on to a classroom wall.

Meanwhile, back at the headquarters of the West Rand Administration Board, which runs Soweto for the Department of Bantu Administration, the chief director, Mr J. C. de Villiers, is enjoying a cup of tea with his boss, Manie Mulder (brother of the Interior Minister, Connie Mulder). An official interrupts them to say that ‘there have been problems at a school again. Shooting has started and police dogs have been stoned to death.’ By now Soweto is ‘out of control’.

Meanwhile, back at the headquarters of the West Rand Administration Board, which runs Soweto for the Department of Bantu Administration, the chief director, Mr J. C. de Villiers, is enjoying a cup of tea with his boss, Manie Mulder (brother of the Interior Minister, Connie Mulder). An official interrupts them to say that ‘there have been problems at a school again. Shooting has started and police dogs have been stoned to death.’ By now Soweto is ‘out of control’.

The ordinary police cannot cope. Casualties only serve to swell the ranks of the resisters. For the first time since it was formed five months before, the police anti-terrorism unit goes into action. A highly trained group of fifty-five men and three officers is led by the infamous Colonel Theunis Swanepoel, once chief interrogator of the security police. Wearing camouflage uniforms which give the impression that they are soldiers, the members of the task force sweep through the streets of Soweto. Swanepoel alone claims to have shot and killed five ‘rioters’, while his men add another nineto the list. There are less precise figures for the wounded.

Swanepoel, self-styled authority on communist guerrilla techniques, is known as the ‘Red Russian’. He later explains how he dealt with ‘a stone-throwing mob of more than 4000’ in Orlando West. After firing warning shots, he saw one man standing in front of the crowd with arms outstretched and fists clenched. ‘It was the sign resembling the horns of an ox, and I noticed the crowd had suddenly closed in on us, approaching in flanks from the left and right. I fired directly at the leader, who staggered back and vanished in the crowd, and then I fired at the “lieutenants” on both flanks.’ Swanepoel explains that this ‘ox-horn’ sign is a ‘well-known communist tactic’, a method used in England and America.

It is two-thirty in the afternoon when the Minister of Bantu Administration and Development, M. C. Botha, introduces to the all-white Senate in Cape Town the second reading of his bill to give the Transkei Bantustan its constitutional ‘independence’: ‘Today is also a day of hope and vision for the future,’ he says. ‘We look forward to and cherish the hope that here beside us another autonomous and mature nation will flourish. Mr President, in all sincerity I want to express the wish and request that the proceedings that will now follow in this House and determine the fate of millions of people and various national groups in this country will be treated with the seriousness and dignity they deserve.’ So saying, the man most directly responsible for the events of Soweto that day begins a discussion that he hopes will solve his country’s ‘black problem’.

But the promise of independence in the Transkei does nothing to allay the distrust of the demonstrators in Soweto. By mid-afternoon they have been joined by the unemployed thousands of the township, and a sprinkling of tsotsis.** Some 30,000 bitter blacks are in the streets. Police drop tear-gas from Alouette helicopters. But the perennial haze from tens of thousands of coal fires and the shroud of smoke from the blazing buildings make pin-point accuracy impossible.

By early evening black men and women are streaming back home from their jobs in Johannesburg. They have heard reports of the shootings and are desperately anxious to learn the fate of their own families. At Inhlanzana railway station, commuters are met by a posse of police who look as though they are expecting trouble. They are not disappointed. As a huge crowd of Africans builds up, the police fire tear-gas, to which the commuters respond with bricks and stones. The parents of Soweto, for so long cut off from their better-educated children, have become part of the struggle.

In the darkness, police stand waiting for vans to pick up the corpses and dump them at the nearest police station. Only black newspaper reporters can move about Soweto now, but the police refuse to cooperate in giving any information about the dead. The official figure at the end of the first day is still only three: ‘a young black, an old man and a black policeman’.

Rumours are rife in Soweto that night. Has not Colonel Swanepoel asserted that the Africans drag their casualties away from the scene of a shooting? (‘It is an old Bantu custom,’ he is to explain later, ‘to remove the dead and injured from the battlefield.’) Later, the ‘official’ figure for Day One will be twenty-five dead (including two whites) and 200 injured. The second white official to die is Dr Melville Edelstein, a sociologist, who, ironically, had warned the Government that because of its policies resentment was swelling in the black townships.

The Minister of Police, Justice and Prisons, James Thomas Kruger, tells the Press that there has been smouldering unrest in Soweto for the past ten days because of ‘dissatisfaction with the curriculum’. At ten past eight, Nigel Kane reads the news in English on SAT V. The great mass of white South Africa sees the inside of a black township for the first time. The Johannesburg stock exchange takes the news of the rioting ‘calmly’, but in the city of London gold shares fall 75c to RI 50c, and Harry Oppenheimer’s de Beers lose nearly 15c.

The pink night sky is a reflection of the burning landscape. Blacks roam the streets looking for prey: the beer halls, which provide much of the revenue to administer the apartheid township; the Administration Board offices, where the rent records are kept; the schools which instruct the hallowed tenets of Bantu Education, the white-owned blacks-only buses. At 2 a.m. Barclay’s Bank International in Dube is burning fiercely. Members of the student movement’s action committee meet to plan their response to the police shootings. The ‘sell-outs’ —black policemen and Government officials, urban Bantu councillors, security police informers, any black man or woman who works for the ‘system’ — lie low.

All whites have been evacuated, except for the handful who are hiding at the homes of friendly Africans, or the heavily armed policemen, racing through the streets in patrol vans and shooting at random. A convoy of fourteen Hippos, anti-riot personnel carriers, arrives from Pretoria. The army is placed on stand-by, and units of the Witwatersrand Command defend the Orlando power station on the border of Soweto. A ring of policemen, commandos, police reservists, cuts off South Africa’s largest city from the rest of the world.

The headquarters of Mr Vorster’s security operation, Orlando police station, has become a fortress. In one of the cells is Mrs Oshadi Phakathi, president of the Y W CA and director of the Christian Institute in the Transvaal, who has been locked up after intervening on behalf of an arrested schoolteacher. ‘Throughout the night,’ she said later, ‘we heard shooting in the streets and in the police station. In the cells next to ours, we heard police assaulting the inmates, who were fighting back. Then there would be a shot … and the screaming stopped straight away. Then we heard a voice in Zulu: “ Izani nimkhipe, o se a file, ni mbulele” (Come and take him out, he is dead, you have killed him….). The door would open and close … it happened all night and the next.’

Mrs Phakathi said that two girls, covered in blood, were pushed into the cell. ‘They described how they had arrived in a van loaded with corpses and injured people. The corpses were dumped on one side, and the injured laid flat on their tummies with hands spread out, and then policemen walked on them till they died and were thrown into the pile of corpses.’

The late—night T V news in Afrikaans has an extensive coverage of the events, but fails to mention that the Afrikaans language is the immediate cause of the trouble. Already some whites are asking why all the early-warning signals were ignored. As early as January 1975, the African teachers’ association had told Minister M. C. Botha that the policy of forcing Afrikaans in black schools was ‘cruel and short-sighted’. But when the Minister was asked whether he had consulted the black people over the ruling, he replied: ‘No, I have not consulted them and I am not going to consult them.’

Now, Deputy Bantu Education Minister Andries Treurnicht complains: ‘In the white area of South Africa, where the Government provides the buildings, gives the subsidies and pays the teachers, it is surely our right to determine the language division.’ And he asks: ‘Why are pupils sent to school if they don’t like the language divisions?’

By the end of the first day of the rebellion, however, it is clear that the Afrikaans-language issue is merely the pin of a hand-grenade that is packed with the many grievances of South Africa’s urban blacks.

The next morning, Die Beeld, an Afrikaans newspaper supporting the Vorster regime, asks: ‘Has our government really no effective weapon other than bullets against children who run amok?’ A Nationalist*** commentator likens the language dispute to the hated policy of Lord Milner when, after the Boer War, Afrikaans schoolchildren were forced to learn through the medium of both English and Dutch. As a black clergyman explains, black children feel that the ‘language of the oppressor in the mouth of the oppressed gives tacit approval to the policy of apartheid’.

A picture of a Soweto schoolgirl carrying the body of a dying boy is splashed across page one of the world’s newspapers.

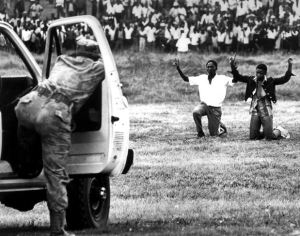

Soon, another photograph — of a Bantu policeman firing into a crowd of Soweto blacks — will do the rounds. Normally, only the rare Bantu sergeant carries a revolver, but as trouble brews there is a wider distribution of arms to the ‘black jacks’ (as the Sowetons call them). On 16 June, with the police taken by surprise, the black jacks begin their training on the spot.

Soon, another photograph — of a Bantu policeman firing into a crowd of Soweto blacks — will do the rounds. Normally, only the rare Bantu sergeant carries a revolver, but as trouble brews there is a wider distribution of arms to the ‘black jacks’ (as the Sowetons call them). On 16 June, with the police taken by surprise, the black jacks begin their training on the spot.

During the night, burnt-out hulks of motor cars have been pushed on to the railway line near Phefeni station,, so that commuter traffic is disrupted. And as the PUTCO**** buses dare not enter the township, many parents are forced to stay at home. Angered by the shootings, some join the protesters. For the deaths, far from dampening down the ardour of the students, have incensed them to further action. The ‘Township’ edition of the Rand Daily Mail, with first-hand accounts by trusted African reporters, is available in Soweto, bringing home the full extent of yesterday’s violence. The people of Soweto now hear that it is the fault of ‘agitators’ and ‘tsotsis’. And if the official death-toll is three, many have seen more bodies than that with their own eyes.

During the night, burnt-out hulks of motor cars have been pushed on to the railway line near Phefeni station,, so that commuter traffic is disrupted. And as the PUTCO**** buses dare not enter the township, many parents are forced to stay at home. Angered by the shootings, some join the protesters. For the deaths, far from dampening down the ardour of the students, have incensed them to further action. The ‘Township’ edition of the Rand Daily Mail, with first-hand accounts by trusted African reporters, is available in Soweto, bringing home the full extent of yesterday’s violence. The people of Soweto now hear that it is the fault of ‘agitators’ and ‘tsotsis’. And if the official death-toll is three, many have seen more bodies than that with their own eyes.

Early in the morning, men, women and children sack a beer hail in Naledi, in the far west of Soweto. When Brigadier Jacobus Buitendag of the South African Railways Police arrives on the scene with two van-loads of men, they are assailed by stones and beer bottles. They shoot the ‘ring-leaders’, but the crowd refuses to disperse. Buitendag is surprised that ‘the people have enough Dutch courage to face shots fired directly at them’. He does not use tear-gas because, he claims, the wind is blowing strongly in the wrong direction. In all, the railway police kill five people at Naledi, and another three at the next station on the line, Merafi.

Thousands of schoolchildren report for classes, unaware that M. C. Botha has closed Soweto schools for the rest of the week. But the older students return to protest, rampaging through the streets in search of targets. More schools and government buildings are razed. There are no white motorists about any more, for a white skin is a death warrant. Every black in a car must convince the students that he does not work for W R A B, then shout ‘Amandla’ (Power) and give the clenched-fist salute. Otherwise, the car is set alight and its occupant beaten up. Students visit African shopkeepers and ask to see their trading licences. If there is white participation in the business, the shop is burnt down. They cross the Potchefstroom Road, which borders Soweto, and burn down half a dozen Indian stores.

There are now 1200 policemen in Soweto, operating from rebellion headquarters at Orlando police station. Many are raw, rural Afrikaner recruits; at seventeen or eighteen, no older than the town blacks whom they are hunting. Alouette helicopters land at the sports field across the road, ferrying canisters of tear-gas. Hippos patrol the streets with guns protruding from the steel windows. Any group of youths standing about on a street corner or walking on the pavement is fair game; the more so, if they are seen giving the black power salute. In Diepkloof the police fire without warning into a group of youths, killing three. A black student says: ‘We will not go into our houses. The streets of this place are all we have and we insist on walking in them.’

Ten miles away, in a white Johannesburg suburb; a teacher discusses Soweto with his English-speaking middle-class pupils, aged between fifteen and seventeen.

Teacher: ‘What do you think of the trouble in Soweto?’

Pupils:[ above the hubbub, is heard] ‘Shoot them’, ‘Kill them all’, ‘Teach them a lesson’.

Teacher: ‘What was the cause of the riot?’

Pupils: ‘Agitators’, ‘Terrorists’, ‘They don’t want to learn Afrikaans.’

Teacher: ‘What do you think about the Afrikaans-language issue?’

Pupils: ‘It’s one of our official languages, that’s the law, so they must put up with it.’ ‘I’m Greek, but I have to learn everything in English.’ ‘Before we gave them schools there was no trouble. Now we are building schools for them and this is all the thanks we get. They should be left uneducated.’

Teacher: ‘If you had to learn biology in Zulu, what would you do?’

Pupils: ‘We’d do what we were told.’

Teacher: ‘I hope you find a teacher, then, because I can’t speak Zulu. Many Soweto teachers can’t speak Afrikaans. They’d lose their job and so would I.’

Pupils: [all boysl: ‘Well, they shouldn’t kill people.’ ‘They are savages.’ ‘They are straight out of the jungle.’ ‘They are so stupid they burn their own buildings.’

A girl: ‘We should feel sorry for the ones who didn’t want to join in.’

A boy: ‘Our girl [maid] told us that two small black kids killed their own mother because she wouldn’t give the black power salute.’

Teacher: ‘They were on strike, peacefully, for five weeks, you know, to try and get the authorities to talk with them. Nobody took any notice. It can’t be very nice

to have no say in the running of your own life.’

Pupils: ‘We haven’t either, no one listens to us.’

A boy: ‘Why should we learn Zulu anyway, what use is it?

Other pupils: ‘Of course it’s useful.’

The same boy: ‘Useful for what? To talk with your garden boy?’

A girl: ‘Very soon it might not be your garden boy, it might be your doctor.’

There is a rare moment of sympathy from white South Africa, as Witwatersrand University students take to the streets of Johannesburg carrying placards proclaiming: ‘Don’t start the revolution without us.’ They are joined by black workers but very soon the march is broken up by a mob of whites, armed with chains and crowbars. Four students are taken to hospital; others are arrested.

Gunsmiths do a brisk trade. Mr Julius Garb, a dealer in Rosettenville, explains that ‘it’s hard to say whether the sudden surge is purely because of the Soweto disturbances. The hunting season has also just opened.’ But at least Johannesburg is clean. The municipal dustmen, who collect the rubbish and sweep the streets of the city and its white suburbs, are housed outside Soweto — and so have no choice but to go to work.

Black nurses at Baragwanath Hospital, on the outskirts of Soweto, protest when armed police refuse to admit a youth with three bullet wounds. In their starched white uniforms they give the black power salute to the black protesters outside the fence. All but six of the medical staff are white, and they are finding it difficult to get through into the hospital. In Orlando East a shop is burnt out when the owner refuses to sell paraffin to students wanting to set fire to a nearby W R A B municipal office. The students are led by the shop owner’s son.

In the afternoon the Diepkloof Hotel, Soweto’s finest, is ablaze. Indeed, nowhere within Soweto’s sixty square kilo-metres can calm be taken for granted. The situation, according to one police source, is ‘under control in the circumstances’, but General W. H. Kotze, head of the police anti-riot squad in Soweto, asks: ‘Can it get worse? We have no contact with the rioters and they have no contact with us.’ He calls for still more police reinforcements.

Back in the Cape Town Parliament, there are calls for the resignation of Minister M. C. Botha and his’ deputy, Andries Treurnicht. In the absence of a statement by Prime Minister Vorster, his Police Minister, Kruger, is left to carry the can. He praises the police for maintaining ‘the greatest measure of self-control’, in face of strong provocation. He entrusts the task of inquiring into the causes of the riots to an Afrikaans-speaking, Government-supporting judge, Piet Cillie. Kruger talks of Herbert Marcuse, and black power and Danny the Red. ‘Why do [the students] walk with upraised fists?’ he asks. ‘Surely this is the sign of the Communist Party?’ And he concludes: ‘It is my task to preserve law and order.’

By the end of the second day, the official count is fifty-four dead, all of them black except for the two whites killed at the start of the uprising. Mrs Phakathi is told by a black policeman at the Meadowlands police station that on the Thursday, he and a colleague collected 176 corpses in one section of Soweto alone.

The police have begun to arrest ‘agitators’, holding them under the no-bail clause of the Terrorism Act. Manie Mulder, the white boss of Soweto, appeals to the youth of his fiefdom, ‘as well as their leaders and elders’, to realize that they will not resolve the issue at stake by vandalizing their assets. He says: ‘Let us come to our senses and discuss the cause of the trouble.’ The students appear to have won a small point.

The violence can no longer be confined to Soweto. In Alexandra, a black dormitory in the heart of the city’s wealthy, white, northern suburbs, schoolchildren burn down administration offices and vehicles, and erect a road block under the banner: ‘Why kill kids for Afrikaans?’At Tembisa, east of Johannesburg, 700 boys and girls match in orderly protest through the streets.

As night falls, student demonstrators in another West Rand township, Kagiso, are joined by adults on their way home from work. The police intervene, and five more Africans are shot dead.

Meanwhile, the bodies of the dead pile up outside the Orlando police station. There are not enough blankets to cover them. Black policemen have rounded up a group of twenty youths, who are led into the courtyard and made to hop for twenty minutes while the police hit them across their bodies with batons and rubber hoses. Under cover of early morning darkness, the youths are forced to load corpses into a mortuary van. White policemen watch the scene, unconcerned.

By Friday morning, white South Africa knows that it has a full-scale uprising on its hands. The ‘unsettled conditions presently prevailing’ persuade the (white) Housewives Le’ague of South Africa to cancel its planned week of protest against an increase in the price of milk. The rebellion roars through seven townships in the Johannesburg area.

The most serious incidents are in Alexandra, home of thousands of black women who work as domestics in white suburbia. Unlike Soweto, which stands on its own in the veld, this is a black enclave, where migrant labourers living in single— sex hostels can compare their dreary lot with that of their prosperous white neighbours. The students and residents come together to vent their anger on white-owned properties. As the Dutch Reformed church, bottle stores, beer halls, the sports club house, a school, Indian businesses are set on fire, smoke drifts across the white suburbs of Bramley and Lombardy West. White shop and factory workers are evacuated as Africans spill Out of the township and burn and ransack white-owned shops. Police, rushed in from Pretoria, cordon off the township, diverting traffic to the near-by Louis Botha Avenue, one of the city’s two main roads to the north. Terrified white families in houses only yards away from Alexandra’s fence hear chanting, shouting and gunfire, and catch a whiff of tear-gas.

The white women’s civil emergency brigades have been called out, but they are not as effective as they should be. The North Eastern Tribune reports later that ‘some of the people who had been trained in the civil emergency units — and particularly those in “Cell I” who were nearest to the riot area —barricaded themselves into their homes. These women all said “my husband will not let me leave the house”. They fried their fish and made their soup for the volunteer firemen, but they would not leave their homes to deliver it to the fire station. It was left to a few of the “brave ladies” to collect and deliver the foodstuffs…’

Colonel Swanepoel and his anti-riot unit are summoned. Swanepoel later explains why tear-gas was abandoned in favour of ‘buckshot’ as a means of ‘quelling the riots’. ‘They would taunt us, throw stones at us and urge us to throw tear-gas. They became very good at handling it. They would just move to the left or right and avoid the fumes. Only innocent bystanders and residents suffered.’ Swanepoel claims that he and his men fired 979 canisters of tear-gas. ‘In the end we had to find another method. We decided not to use Ri firearms which would send the death and injury rate soaring. Instead we chose buckshot, which can seriously injure a man at ten yards but is more of a discomfort at twenty yards.’ At least twenty blacks die from gunfire in Alexandra that day.

Now four black universities, hundreds of miles apart, react in solidarity with the students of Soweto. At Turfloop, in the northern Transvaal near Pietersburg, 2000 University of the North students gather on the football field and pray on their knees for the dead of Soweto. This time the police do not use their guns, but instead they chase students across the campus with batons and dogs. One student jumps to his death from an upper-storey window. The officer in charge, Colonel Matthinus van Zyl, a self-styled expert on ‘Bantu’ behaviour, doubtless recalling the numerous incidents of ‘window-jumping’ by victims of security police interrogation, remarks: ‘It is a phenomenon I have often noticed among blacks. In fact, three students jumped from windows that day. One was unfortunate enough to land on his head.’ 359 students are arrested.

At the University of Zululand, Empangeni, three hours by car from Durban, students drive out the white staff and burn down the administration block, the library and a church. In Durban itself, police arrest eighty-seven medical students from the ‘non-white’ (African, Coloured and Indian) medical school, as they march through the streets waving placards. In Cape Town, at the Coloured (mixed-blood) University of the Western Cape, the staff association affirms its solidarity with the children and people of Soweto and pledges support to free South Africa from ‘racism and oppression’.

At this point, the Government publishes the long-awaited report of the Theron Commission on the future of the country’s two million Coloured people. The two most important recommendations — Coloured representation in the white central parliament and the repeal of laws forbidding sex and marriage between Coloureds and whites — are immediately rejected by Mr Vorster. If the Government cannot make concessions on the Coloureds, who are culturally and racially part of the Afrikaner’s own family, what chance is there of liberalizing the ‘Bantu’ policy?

In Soweto the burning has died down, if only because everything that symbolizes apartheid is already in ruins. The attacks are a mixture of ideology and thuggery: the students aim at political targets, such as government offices, while the tsotsis, the township hooligans and small-time gangsters, loot the bottle stores. If the students do go into bottle stores it is invariably to empty the liquor into the gutter. A puritanical streak runs through the rebellion; whereas, early on Thursday morning, white policemen are seen carrying bottles of whisky from the looted stores to their ‘pick-ups’.

The language of black consciousness is everywhere heard: ‘Azania’ (the name for a black-ruled South Africa), ‘the people’, ‘possessing what is rightfully ours’, and always ‘Amandla’ and the clenched-fist salute, which by now is rewarded with automatic arrest. The tsotsis also demand the salute, but only to see if their victim is wearing a watch, from which he is then smartly separated. They speak a gangster Afrikaans, as if to distance themselves from their fellow blacks.

Now, at last, W R A B officials agree to talk to Soweto ‘leaders’. But the meeting with the normally compliant urban Bantu councillors and school-board representatives is stormy. These ‘uncle Toms’ are conscious that their actions could invite retribution from the students. They refuse to participate in reconstructing Soweto until basic grievances are met. They want Afrikaans removed, the police withdrawn from Soweto, and a multiracial commission of inquiry into the disturbances. Says the Rev. B. Phofolo: ‘If you have a nail through your shoe into your toe, you do not go on polishing the shoe. Let’s remove the nail.’ The only student present, Walter Mazula, tells officials that the students will refuse to have lessons in Afrikaans until the Prime Minister begins to learn Zulu.

In Parliament, Mr Vorster warns that the police ‘have orders to use all the means at their disposal without fear or favour to protect life and property’. Referring to his coming meeting with Secretary of State Henry Kissinger in West Germany, Vorster says: ‘In case, as it appears to me, the idea exists that the Government would hesitate to take action because of my coming talks, they [the protesting blacks] will be making a mistake … However important these talks may be, order in South Africa is more important to me than anything else.’ Brigadier J. J. Visser, Assistant Commissioner of Police on the Witwatersrand, is pleased: ‘I will have the support from above that I want. From now on we will use tougher methods.’ The police announce that they will not publish further figures for dead and wounded until the riots have ended.

Justice Minister Kruger invokes the Riotous Assemblies Act to ban all public meetings for ten days. And two white Christians, Dr Beyers Naude, director of the Christian Institute, and John Rees, secretary-general of the South African Council of Churches, are ordered by the chief magistrates of Johannesburg to ‘dissociate yourselves completely from the present unrest’. Later they are accused of ‘polarizing the races’, though in fact they are trying to bring representatives of the races together for talks. Chief Gatsha Buthelezi, chief minister of the Zulu Bantustan of Kwa-Zulu, arrives in Johannesburg to ‘identify with the people of Soweto’. By nightfall, Soweto’s official death toll is eighty-eight blacks and two whites, with another boo wounded. Mr Thys de Beer, the school inspector, advises the Government ‘not to step down on the language issue’.

On Saturday, Minister M. C. Botha meets Johannesburg ‘urban black leaders’ and says that he has no authority to suspend Afrikaans, because both English and Afrikaans are entrenched as official languages in the constitution. His deputy minister of Bantu Education, Dr Treurnicht, is not present, but he feels that ‘it is for the Bantu’s own good that he learns Afrikaans.’ (Three days later, Botha suspends the compulsory use of Afrikaans and Mr Thys de Beer is transferred to Kimberley. Four other Afrikaans education officials who have been directly implicated in forcing Afrikaans remain in their posts, despite black calls for their dismissal.)

Long queues wait outside the mortuaries, as parents search for missing children. The official death count rises to 109 but after visiting Baragwanath Hospital, Chief Gatsha Buthelezi says that the true figure is closer to 700. Justice Minister Kruger denounces the claim as ‘irresponsible and unfounded’, and makes some claims of his own. He says that the riots were ‘definitely organized’, and names ‘black power movements’ like the South African Students’ Organization and the Black People’s Convention. Answering criticism of the high death toll, he says that the police did not use rubber bullets because they make people ‘tame to the gun’. Later, pathologists will find that more than half the rioters killed by police in Johannesburg were shot in the back.

On Saturday afternoon, Prime Minister Vorster flies off to West Germany for talks with Henry Kissinger. Their primary objective: to bring Ian Smith to his senses over the deteriorating racial conflict in Rhodesia.

Soweto, the police report, is ‘calm but tense’.

Footnotes

*Bantu is the term for a group of languages spoken as far north as the Gulf of Guinea. The word -ntu simply means ‘a person’ (Bantu — people), but apart from its vagueness, the association with apartheid — and the fact that it was foisted on blacks by whites — makes it unacceptable as a description. The youth now refer to all ‘nonwhites’ as ‘black’, but where necessary for purposes of clarity I have stuck to ‘African’, ‘Coloured’ and ‘Indian’.

**Mostly primary school drop-outs, aged fifteen to late twenties, who have adapted to the lawless life of the townships by thieving (with or without violence), dagga (marijuana) smoking and wearing racy clothes. The word could be derived from the Sotho ‘,notsu’ (sharp), perhaps referring to their traditional weapon — the thin wire that glides between the ribs in a fight. The pointed shoes and stove-pipe trousers were once known as ‘zoot suits’, and could have been transformed into tsotsis. To be contrasted with the genteel township middle class, the ‘oosczese-me’ (sing. wscuse—me).

***The Purified National Party was founded in 1934 by a group of Afrikaners under Dr Daniel Malan, who refused to follow General J. M. B. Hertzog’s old National Party into a coalition government with General Jan Smuta’s largely English-speaking South African Party. By the end of the Second World War, the Malanites drew majority Aftikaner support. They won power in 5948, and have ruled South Africa ever since. ‘When the Hertzogites returned to the fold, it became the Reunited National Party. Afrikaans newspapers are invariably official organs of the Party.

****The privately-owned Public Utility Transport Company provides bus transport between the city and most Rand black townships.

The Year of the Schoolchildren (chapter 6 of Herbstein’s book)

An icy wind drove through Soweto that first week-end of the uprising. The people withdrew to lick their wounds and count their dead. It was by now obvious that there was more to ‘Soweto’ than a mere objection to the enforced use of Afrikaans. ‘To say that the uprising was over Afrikaans language instruction,’ one black remarked, ‘. is like saying that the American revolution was over King George III’s stamp tax.’

By Sunday night, the rebellion was launched on its nationwide spread; first to Pretoria and other Transvaal towns, then to the ‘homelands’, and eventually to the Coloured communities of the Cape. In practically every township where the youth organized protests in solidarity with Soweto, the police – all peas out of the same Transvaal pod – reacted by opening fire. In each black and Coloured township, the parents, workers, and in the end, after some false starts, the migrant workers, reacted by joining in the rebellion as well.

The defiance of black people was much more sustained than the protests which followed the shootings at Sharpeville. This was largely attributable to the vastly improved network of communications that stretched across black urban South Africa. There were black newspapers now, and there were also blacks working on white newspapers, even Afrikaans ones. The day after the first shootings, any black virtually anywhere in the whole vast country could read an eye-witness account of how a Soweto girl had been shot in the back while going to the corner shop to buy margarine for her mother. The report was by-lined in the unmistakable syntax of an African, and the picture was attributed to Peter Magubane or Willie Nkosi. If the radio maintained its blindfold version of the events, the television cameras were unable to obliterate the open rebellion. Few blacks owned sets…

With the police facing growing criticism, Kruger went out of his way to ‘pay tribute’ to the nineteen white policemen who had died while on duty during the previous year. Reminded that sixteen ‘non-white’ policemen had also died, sympathy was duly extended to their families as well. His words set the tone. One MP praised the ‘superhuman self-control’ of the police in Soweto; a colleague declared that ‘any South African — white citizen, immigrant, black, Coloured or yellow — who does not want to associate himself with the action of the police outside [Parliament] does not belong in South Africa.’

The public relations offensive included a statement that morning by the Commissioner of Police that only forty-two of the 130 blacks killed had died at the hands of the police. Later Kruger was to say that .22 bullets were found in twenty-two of the bodies, and as the police did not use this calibre ammunition they could not have been responsible. The implication was that Africans had shot Africans. The fact that no policeman had been shot by .22 bullets, however, pointed a finger at white free-lancers from among one of the world’s most heavily armed communities.

Kruger’s colourful turn of phrase was brought into play to answer opposition queries over why bullets and not water-cannon had been used on the students, and why the police had not worn face guards. He rightly pointed out that face guards were unnecessary because policemen were not ‘injured on a large scale’ and he added: ‘Therefore to have our policemen running around like knights of the Middle Ages, heavily armed with coats-of-mail and visors and goodness knows what else —policemen in such a garb pursuing fleet-footed little Bantu all over the veld — is something I can hardly imagine.’

If Parliament had intended to inform an anxious public of the reasons for the previous week’s momentous events, it proved incapable of doing so. It was left to Mr Langley to lament:

‘Where do those riots come from all of a sudden, now that we should be reaping the fruits of the years of positive work to establish a model state in South Africa?’

There was one white man who had taken the call for change seriously. Just as the students were beginning their protest, the stationmaster at the Transvaal country town of Standerton had removed the ‘whites only’ signs from the lavatories, waiting rooms and even the pedestrian bridge. There was no reaction for a few days, then a white resident complained. Out came the white paint and the signs were restored. ‘Nobody meant him to go that far,’ said a railway official.

At Atteridgeville, near Pretoria, posters went up proclaiming ‘Don’t pray — fight’ and ‘Support Soweto’. On the Monday the township of Duduza, near Nigel (which Mr Vorster represents in Parliament), was astir. Ten more people died that day in townships near the capital, while bottle stores, municipal buses and government buildings went up in smoke.

Though the security forces had ringed off the townships there were isolated reminders to whites that their lives were in danger as well. Blacks from the township of Mabopane invaded the nearest white farming disLrict, Rietgat. In days reminiscent of the ‘kaffir wars’, women and children were evacuated to Pretoria while patrols of armed white vigilantes guarded their farms. One optimistic farmer thought that the trouble would soon pass, ‘like the drought or the measles’.

And though the black workers of Johannesburg remained outwardly calm, their despair was getting out of control. In the middle of the city, in the gardens of the city hall, a black man wielding an axe and demanding ‘revenge for the children of Soweto’ injured four whites, before he was shot by the police. He was taken to police headquarters at the near-by John Vorster Square, but within minutes he had ‘fallen out of a fourth-floor window’. Nothing has been heard of him since.

The rebellion spread rapidly to several Bantustans. In Bophutatswana — which had townships within commuting distance of Pretoria, and tribal areas in the Cape Province and the Orange Free State — schools and training colleges were stoned and burned down by angry students. The Tswana chief minister, Lucas Mangope, was particularly unpopular for his enthusiastic conversion to ‘separate development’ and his declaration that the Bantustan would follow the Transkei to ‘independence’. Two opposition MPs in Lebowa, a Bantustan in the eastern Transvaal, issued a statement declaring that ‘the situation has unearthed the innermost frustrations of the black people, which were hidden from the outside world.’ The determination of the students and their contempt for separate development was going to make it more difficult for Mr. Vorster to sell independence to other tribal leaders.

The uprising also exposed the chasm that separated the mental attitudes of teenagers from those of their parents. In traditional tribal society children were meant to be seen and not heard. Now, in many urban families, the reverse was true. Parents had lost status in the eyes of their children. ‘We cannot take it any longer,’ one student lamented. ‘It is our parents who have let things go on far too long without doing anything. They have failed. We have been forced to fight to the bitter end.’ One parent, in the language that reflected the anguish of the times, said, ‘they will spit on our graves when we are dead.’ When parents complained that ‘we can’t talk to our children any more’, it sounded like an echo from the West.

But the rift in Soweto was not the traditional ‘generation gap’. Both generations understood only too well the nature of their common grievances. The parents, however, were so bound down by long hours of work and travel, by rising prices and the insecurity of their jobs and homes, and the need to find the money to educate their children, that it was very hard for them to step out of line.

A Johannesburg psychiatrist has suggested that children in black areas resorted to violence as a result of the breakdown of home life and the indignities to which their parents were subjected. Better educated, without the responsibility of supporting a family, and with time on their hands, schoolchildren were the obvious spearhead of demands for political action. Now, the barricades, the running battles with the police, the sleepless nights on the run, the deaths and injuries of schoolfriends, had raised their defiance into a truly revolutionary mood.

A week after the beginning of the uprising, a group of respected leaders in Soweto founded the Black Parents’ Association (BPA) with a primary aim of bringing children, parents and teachers together. Its leader was the Lutheran churchman Manas Buthelezi, a cousin of the Zulu chief minister, and a man once banned under the Suppression of Communism Act until world-wide protests persuaded the Government to revoke the order. Another prominent BPA member was Winnie Mandela, herself a long-time victim of bannings and imprisonment without trial.

The B PA did attempt to talk to the Government on behalf of the students. Its leaders took pains to make the point that they were simpiy acting as a conduit for grievances. However, there was no positive response from any cabinet minister.

The Government, having destroyed every representative black political organization, bad nobody to negotiate with but the discredited Urban Councillors. Minister Botha, who had treated them with contempt for years, now attempted to bolster theit standing. On 21 June he announced that in future there would be ‘continuous consultation’ between black urban leaders and white authorities, and that these discussions would not be limited to the language issue. The black ‘leaders’ were grouped into a Government-tacked ‘Committee of Thirty’.

On 6 July, M. C. Botha, following discussions with these ‘leaders’, announced the first major concession: school principals would be able to choose the medium of instruction, Appearing on television that night, Botha tried to cover up the retreat by claiming that principals had always had a choice, that there had been ‘confusion’ over the matter.

No such platform was allowed to the secretary-general of the Black Teachers’ Association, Mr H. H. Dlamlense, when he referred to departmental circulars which stated categorically that social studies and arithmetic must be taught in Afrikaans. Principals had been able to apply for an exemption, said Mr Dlamlense, but these applications had been refused.

The teachers’ union had other demands: among them, the removal of six senior white Bantu Education officials and the reinstatement of the dismissed school board. A fortnight later, Joseph Peele and Abner Letlapa were reappointed to the Meadowlands Tswana school board by the Department of Bantu Education, while Mr W. C. Ackerman, regional director of Bantu Education, and the circuit inspector Thys de Beer were told to expect to be transferred. Never before in twenty-eight years of Nationalist rule had blacks persuaded their masters that some aspect of apartheid might be unacceptable. Now they had done it by the use of force. The lesson was not lost on the protesters.

One other task of the Black Parents’ Association was to arrange for the burial of the dead. But the chief magistrate of Johannesburg refused permission for a mass funeral. Dr Aaron Mat]hare, one of a handful of black doctors practising in Soweto, was told that ‘if a mass funeral were to be allowed, the police would have to be there and that could spark off more trouble.’

By the end of June, two state mortuaries — at Hillbrow and Fordsburg — were full to overflowing, despite the fact that the piles of black bodies were being ceaselessly carted away. The dead were also stored in Soweto police stations. These inadequate facilities provided scope for commercial enterprise. A man looking for the body of his brother-in-law was confronted by a group of black men in camouflage uniforms sitting around a fire in the grounds of Moroka police station. ‘One approached me and said I would have to pay R200 if my brother-in-law had been killed by a bullet, because the Government needed the money to rebuild Soweto.’

The exact, or even approximate, number of dead was a matter for widely diverging estimates. But rumours abounded of mass burials in the grounds of police stations and of mysterious ‘undertakers’ who buried bodies at night. For some time police patrolled all cemeteries, day and night. One grave-digger reported having dug a number of new graves each day and finding them filled in the next morning.

On one matter there was little doubt. The police reacted to demonstrations by blacks with bullets only. Chief Gatsha Buthelezi reflected the opinion of most blacks and many whites when he lamented that South Africa had learned nothing since disasters: from the Congo, through innumerable coups and counter-coups, to the person of President Idi Amin of Uganda. (The Israeli raid on Entebbe and the humiliation of Aniin provided a heaven-sent opportunity for the S A B C to take the minds of its listeners away from the townships.)

Unlike the days after Sharpeville, there was now no ‘state of emergency’. It did not matter that South Africa, thanks to half a dozen detention-without-trial measures, was living under a permanent but undeclared state of emergency. This time, the only whites to be arrested were students from the universities of Cape Town and the Witwatersrand.

Mr Vorster conveyed the impression of stolid realism, which for the Western world meant that the man would protect its investments. The blocked rand prevented an outflow of foreign capital. In the first week of July the Financial Mail surveyed the country’s top executives. Its conclusion: ‘Caution — yes. Pessimism — no. The [average businessman] has noted the muted reaction overseas and has drawn comfort from it; he is confident the wrath of the world is not about to descend on South Africa and snap his foreign trade and investment links.’ This view would have to be revised in the months to come.

After a week, Soweto was reasonably quiet, its inhabitants sullen and tense. The road blocks had been removed, including the sewerage pipe with the words ‘Kruger, we want to see you’ painted across it. Hundreds of boys and girls, some only eight years old, were in prison. The police at first denied that any chijdren were in custody. But when reporters claimed to have seen them in prison they were told: ‘What do you think would happen if we let them run around the streets? Do you think that we would ever find them again?’….

*****

…. though the ‘agitation’ had by no means eased, he [Kruger] allowed the schools to reopen on 22 July. Few pupils turned up. Heavy police-patrols drove other students off the streets. Soweto’s 400 school principals, anxious to get classes back to normal, called for the removal of the ‘hippos’ from the vicinity of schools. Colonel Jan Visser of the C I D explained that the police were there ‘to protect the public in cases of intimidation.

Demonstrations began again with stones thrown at police and schools being fired. Kruger received the favoured Urban Bantu councillors and promised that the police would stay away from school premises during lesson times. The concession made no difference, though the student leader Tsietsi Mashinini lent his weight by urging a return to school and an end to arson. The police, for their part, were incapable of leaving matters alone. They entered a number of schools in a search for partisans of black consciousness. The unwelcome visitors were taunted, and clenched fists were thrust in their faces, even though, the week before. Two blacks had been sentenced to three years’ imprisonment for giving the black power salute in Alexandra. The police opened fire.

The following day, Wednesday 4 August, marked a significant point in the Soweto struggle. The Students’ Representative Council (S R C) had used the time to develop a basic strategy. They understood that the bravery, perhaps even the foolhardiness, of their colleagues in the face of police bullets was admirable, but it hardly seemed to dent the complacency of the white suburbs and city, cosily sealed off from the explosion a few miles away. Now parents were told to stay away from work as a show of solidarity in the campaign for the release of detained student leaders. To encourage the strike, the traffic control mechanism of the Soweto railway line was sabotaged, and passenger coaches were stoned. It was a three-cornered battle, as parents resisted their children, and the police stepped in to restore order in their own way. At times it was vicious: a black woman broke her neck jumping out of a bus under attack by students.

The reasons for the parental resistance might have been found in the latest poverty-datum-line figures for Soweto, published the week before by the Johannesburg Chamber of Commerce. In the previous six months the cost of living had risen 55 per cent — including a 7 per cent increase in the price of food, which accounted for over half of the average Soweto’s family budget. At the end of the day, Mashinini declared his disappointment at ‘the number of parents who went to work this morning when we pleaded with them that they should not do so until our brothers are released’.

Mashinini had underestimated the success of the stay-away. The streets of Johannesburg were empty; some factories and stores were without half to three quarters of their black work-force; and often those workers who did arrive came from Alexandra or the edges of Soweto. One industrialist received a deputation of black workers asking him to tell newspaper inquirers that nobody had turned up for work that day. Who worked where was common knowledge in Soweto.

Whites had to take over black jobs: they sold newspapers on street corners and carried messages about the city; white office workers waited hungrily at undermanned lunch counters. It was a taste of the event long feared by white employers — the general strike.

Inside Soweto, the police were again shooting students in an effort to counter that other white South African fear — an invasion of their suburbs by a black mob. Students and their supporters, estimated by the police at 15,000, began a march which they hoped would reach police headquarters at John Vorster Square. Here they would demand the release of their colleagues and ask for an interview with Justice Minister Kruger.

They marched in school uniform, some carrying the optimistic banner: ‘We are not fighting, don’t shoot.’ Near the New Canada railway station, the main junction into the city, the police were waiting. But, anxious to avoid bloodshed, the police sank their pride momentarily and chose the only people they knew who might have some influence with the marchers — the Black Parents’ Association. Dr Buthelezi and Mrs Mandela pleaded with the students not to proceed, but they were angrily dismissed. Battle recommenced.

By now, the students had acquired some amateur antidotes to the weapons of the enemy. Women had brought along bottles of water, and after each tear-gas attack, they washed out the eyes of friends who had come close to the exploding canisters. Some marchers fled up near-by mine dumps and regrouped, trying again to break the police cordon. The police opened fire and three more died.

With Soweto ringed off once again, armed police reserves manned road blocks, pulling homeward-bound blacks out of cars, searching and insulting them. One reservist, an immigrant, was heard to tell a passing African motorist: ‘We will call in the Army and shoot all you kaffirs down.’ A young government official told a group of Coloureds: ‘You hotnots [a perjorative term derived from Hottentots] should also be shot.’ In that atmosphere a white traffic cop on point duty at the road block was run down and killed by a black truck driver. He was the third white to die in the month and a half of disturbances.

The students did not break through the cordon. They went on the rampage in Soweto burning down the one beer hall that had survived, and razing the homes of black members of the special branch. That night, too, petrol bombs were thrown through the windows of the houses of Winnie Mandela and Dr Aaron Mathlare. Mrs Mandela was not at home, which was fortunate as she invariably barricaded herself in at night and would have had some difficulty escaping. The police tried to blame the arson on students who, it was suggested, might have been annoyed at the Black Parents’ Association’s efforts to stop the march on Johannesburg. In Soweto, however, it was widely believed that the culprits were the police themselves. Said Mrs Mandela: ‘No black man throws a bomb at the home of Nelson Mandela.’

By the end of the week, eight more blacks had died. The police were now on stand-by throughout the country. Soweto was closed once again to whites. The stock exchange was knocked flatter than ever. Mashinini had gone into hiding, vowing that ‘we won’t rest until our objectives have been achieved.’…..

*****

….So nervous were the authorities that they even arrested Steve Biko, the 29-year-old father-figure of black consciousness, despite the fact that he was already banned under the anti-communism laws. Several other black leaders in the Kingwilliamstown area of the old British Kaffraria were detained. The police there were particularly sensitive to the possibility of repercussions following the death in a local prison of Mapetla Mohapi, one of the most promising black consciousness leaders. Mohapi, aged twenty-five, a social science graduate, was at the time of his death administrator of the Zimele trust fund, which cared for released political prisoners and their families. He was a level-headed man, and during his detention had smuggled letters to his wife, which had not indicated ‘any desperation or frustration’. Yet on 5 August the police claimed that he had committed suicide in his cell by hanging himself with his jeans. When she identified her husband’s body, Mrs Mohapi said she had seen no evidence of suicide. The two African doctors who attended the post-mortem examination were themselves detained, thus making it dangerous for them to communicate with the family solicitor.

The chairman of the Zimele trust fund, Mr M. Tembeni, commented that black people were ‘highly suspicious of the frequent alleged suicide incidents among people detained under the Terrorism Act’. He, too, was detained. Perhaps the best clue to the circumstances of the ‘suicide’ came from an African woman journalist, Tenjiwe Mthintso, who was detained by the same security police squad. On one occasion they put a wet towel round her neck, telling her: ‘Now you know how Mapetla died.’

All the while, black people in ever increasing numbers were going out intO the streets to express their hatred of ‘the system’. At Fort Hare in the eastern Cape, students met to discuss a day of prayer for Soweto. The meeting got out of hand, the university was closed down, and its students were sent home. The near-by Lovedale teachers’ training college was extensively damaged by fire. In Zululand the university would remain closed till the end of the year. Students marched through a township near Mafeking, in the Cape section of the Bophuthatswana Bantustan, and a black ‘Guy Fawkes’ burnt down Chief Mangope’s parliament building. The disaffection reached Mdantsane, the giant Ciskei township which supplied labour to East London; and then Cape Town, the legislative capital, where the fighting was even fiercer than in Soweto.

M. C. Botha chose the moment to make another important concession, On 14 August he announced that the leasehold for Africans wanting to acquire their own homes in a ‘white’ town would no longer be dependent on producing a certificate of citizenship in a Bantustan. Furthermore, the lease would be for an unlimited period, not just for thirty years; though Botha later reverted to type by reminding blacks that they were present in white areas ‘to sell their labour and for nothing else’.

Within days of the ‘concession’, Port Elizabeth, the country’s fifth largest city, was the scene of a two-day flare-up in which thirty-three blacks died at the hands of the police. The men who marked the incidents on the map of South Africa at police headquarters in Pretoria were having to work overtime.

Later, the senior state pathologist at the Johannesburg mortuary, Professor Joshua Taljaard, disclosed that, up to the end of August, the majority of blacks killed by police bullets in the townships around the city had been shot in the back. Giving details of post-mortem investigations, Taljaard said that eighty people had been shot from behind, forty-two from the front and twenty-eight from the side.

By the end of August, 800 people, including seventy-seven black consciousness leaders, were in detention without trial. Students were arrested at a meeting in Daveytown, near Germiston, and brought before the local magistrate. There were no defence lawyers. They were quickly convicted and most of them, including nine children under the age of sixteen, were given cuts (strokes of the cane).

A senior riot squad policeman prophesied that the violence which had disrupted South Africa for two months was in its ‘final throes’. The assessment was hopelessly wide of the mark, for, by then, rebellion had erupted in the Cape Peninsula. What should have worried both white police officers and theoreticians of separate development was the cross-racial nature of the protest.

Students at the Coloured university of the Western Cape in Bellville South (Belville proper is the centre of the peninsula’s largest Afrikaner population) and other black consciousness supporters at high schools and training colleges demonstrated with the Africans of Soweto. The police held off and there was no bloodshed. Early in August, the students began a week-long boycott of lectures. Their Coloured rector, Dr Richard van der Ross, suspended lectures altogether; to the fury of his students, who regarded this as a betrayal of their cause. The whites-only staff association (only a handful of lecturers were blacks) dissociated itself from the student protest. The students set up road blocks outside the university. The police were called, and their vehicles were stoned. Soon enough, the administration building was in flames and other educational institutions were set on fire. The process of action and reaction between Coloured students and police was heading for bloodshed. But when this came, on 11 August, it took place not in the Coloured areas but in the three African townships of Langa, Guguletu and Nyanga.

It was surprising that the rebellion had taken so long to reach Cape Town. The city’s 200,000 Africans were the worst-off of all the country’s urban blacks. The thirty-year leasehold concession was never available to them, because white politicians still cherished the hope of one day expelling every single African, whether migrant worker or ‘bonier’, from the western Cape. Langa had the highest proportion of ‘single-men’ hostel dwellers of any township in the country. Many had seen their wives and children driven out to the Bantustans under the influx control laws. Their sense of insecurity was heightened by the prospect of being forced to become Transkeians (they were nearly all Xhosa) when the first Bantustan became independent in October.

The trouble began with a Soweto sympathy march by Langa high school pupils, stones thrown at a bottle store, a police order to disperse in five minutes, tear-gas and more stones, clashes in the two other townships, government buildings ablaze and, finally, police roaming the streets taking pot shots at the young protesters. By morning sixteen blacks were dead.

The confrontations continued into the next day. In Langa, students paraded placards proclaiming ‘We are not fighting’; but they were gassed and shot all the same. White students marched from their ivy-leafed campus on the slopes of Devil’s Peak. The show of solidarity led, as the townships began to burn, to seventy-six arrests. One hundred and thirty riot police were airlifted from the Reef under the direction of the veteran of Soweto, Brigadier Visser. He had been sent down to stop the rioting, he said ‘and that is just what I am going to do.’ By the next morning another seventeen Africans were dead.

The success of the August stay-at-home had demonstrated to the students of Soweto that the one really weak point in the fortress of apartheid was the white man’s almost total dependence on black labour. Increasingly, this was to become a major factor in their planning. Now the S R C prepared for a three-day general strike starting on 23 August. Blacks with access to photocopying machines at their places of work produced pamphlets; posters went up at street corners; and in the homes of Moroka, Dube and other Soweto suburbs, fathers were told by their twelve-year-old children: ‘On Monday, Tuesday and Wednesday you are staying away from work. Just to ensure that you do, will you please see to it that your car stays in the yard.’

Over the week-end the students delivered leaflets to houses, to emphasize their point:

The racists, in our last demonstration — called by the cynics a riot — lost millions of rands as a result of the people not going to work. Thus they thought of immediately breaking the student— worker alliance, [and] called on workers to carry knobkerries and swords to murder their own children who are protesting for a right cause. Parent-workers, you should take note of the fact that, if you go to work, you will be inviting Vorster to slaughter us, your children

…. We want to avoid further shootings. Parent-workers, heed our call and stay away from work.

The anonymous leaflet recalled that: ‘Vorster is already talking of home ownership for blacks in Soweto. This is a victory achieved because we, the students, your children, decided to shed their blood.’ The clandestine African National Congress lent its weight to the strike, printing and distributing leaflets in its own name.

The ‘Azikhwelwa’ call — the word, ‘we won’t ride’, had its origins in earlier bus boycotts (Samotnaf note: see “The Lessons of Azikwelwa” by Dan Mokonyane )— resulted in an absentee rate of up to 80 per cent in Johannesburg, with the supposedly apolitical manual labourers especially solid. And the alarming fact for white employers this time was the relative absence of intimidation by students. No barricades went up in Soweto to prevent workers from travelling into the city. Students did picket railway stations, but they were heavily outnumbered by police. The taxi drivers, who were affiliated to the parents’ association, took the day off, while the municipal buses had not dared enter Soweto for several weeks.

The only substantial group to ignore the strike call were the hostel dwellers, who had been given a free hand by the police to arm themselves (with knobkerries or wooden clubs) against the students without fear of prosecution.

At Orlando station, police fired on students, killing a bystander on his way to work. By mid morning strike-breaking workers were trickling back to Soweto, either because they and their employers feared reprisals or because there weren’t enough men and women to keep the production lines moving. Two student picketers were beaten to death by returning hostel dwellers. That night, rooms in the Mzimphlope hostel in Orlando West in were burnt out. It was the pretext for a police-encouraged backlash that led to forty officially-admitted deaths in the next week.

The stay-away held firm on the Tuesday. In the old days, strikes had been broken by the simple device of sending policemen to round up or assault every adult who was not at work. This time, perhaps fearing that such methods would have the opposite effect, the police contrived to set black against black. The hostel dwellers were used for this purpose.

The hostellers, as we have seen, are the premeditated result of the policy by which Africans are uprooted from their homes in white cities, dumped in the tribal areas, and allowed to return to Johannesburg, or wherever they are needed, in the guise of ‘bachelors’. In Soweto they included one-year contract workers, but also a fairly large number of people, especially Zulus, doomed to live there for much of their working lives.

Often, twenty men are housed in a bleak dormitory, devoid of privacy, family warmth and lasting friendships — a prey to all manner of social and psychological evils that were uncommon in traditional society — broken marriages, homosexuality, prostitution, venereal disease, alcoholism. To Soweto residents, hostel dwellers were country bumpkins, and contact between these two well-defined sections of township life was scant. Now, boys and girls still in school uniform had the impertinence to order the hostellers not to go out and earn their keep. Nobody bothered to tell them what the strike was about. The fires in the hostel had destroyed not only their worldly possessions, but also their earnings, stored in boxes under their beds for dispatch to destitute families in the Bantustans.

The ‘backlash’ had been prepared in advance of the strike. On the preceding Sunday, security chief Mike Geldenhuys had warned that ‘agitators who attempt to enforce a work stay-away will experience a backlash from law-abiding citizens in the townships.’ On the Tuesday, the World, the African newspaper, quoted Colonel Visser, head of the Soweto C I D, as telling people to go to work ‘and just thrash the children stopping them’.

On Tuesday evening, a thousand frenzied Mzimphlope Zulus, armed with knobkerries, pangas, assegais, rampaged tbrough the streets and into the private houses of Orlando and Meadowlands, robbing, raping, killing. The ‘Zulu warriors’ banded together into impis’ and scoured the streets for cheeky children, terrifying the residents. They were led by police ‘hippos’ which fired on groups of youths who were blocking their way in an effort to defend the houses. Having cleared a path, the police then stood aside, sometimes shouting the two Zulu words that they had lately acquired — ‘Bulala zonke’ (kill them all) — before leaving it to the impis to impose law and order. Panic-stricken housewives seeking help at the Orlando police station were reminded that ‘you did not want protection to go to work, so why do you want it now?’.

Confirmation of the central role played by the police in inciting the ‘backlash’ came from a black reporter on the Rand Daily Mail, Nat Serache. Finding it necessary to escape from the mob — while on the look-out for a good story — he hid all night in a coal box near one of the hostels. At 2.15 a.m. he heard a policeman with a loudhailer tell the hostel dwellers not to raid and damage houses, which after all belonged to the government. ‘We didn’t order you to destroy West Rand [Administration Board] property,’ the police voice said in Zulu. ‘You were asked to fight people only, so you are asked to withdraw immediately.’ And peace was immediately restored in Orlando West.

Another black journalist, this time from the Star, got into the Mzimphlope hostel, where he heard a white policeman, dressed in a camouflage uniform, tell the hostellers through an interpreter: ‘If you damage houses you will force us to take action against you to prevent this. You have been ordered to kill only these troublemakers.’ Two hostel dwellers were later shot while disobeying instructions.

The Wednesday stay-away figures were as high as ever. The police swept through Soweto in convoy, shooting and rounding-up students. Minister Kruger commented: ‘The situation will calm itself once people realize there is a strong backlash.’ On the Thursday, the three-day strike having achieved its aims, the workers of Soweto returned to their jobs. The ‘backlash’ had nothing to do with it.

It was known in Soweto that the police had used the Zulu cultural movement Inkatha to orchestrate the hostel violence. Chief Gatsha Buthelezi, as founder of Inkatha, made an early call on his members to stop fighting. When he flew into Johannesburg from Durban he was warned by Kruger not to interfere. But Buthelezi’s representative in Soweto, Gibson Thula, also warned him that if he did not intervene he would never gain the support of the people of Soweto. On the Friday, Buthelezi met the hostellers and afterwards told reporters that the Zulus had been given dagga (marijuana) by the police, who had encouraged them to kill and even driven them to areas where crowds were gathering. The hostel dwellers, he said, had been joined by heavily-armed black groups, whose black boots ‘looked similar to those worn by the police’.

Now, for the first time, the migrants were told what the strike was about. Buthelezi apologized to the people of Soweto on their behalf. The students rushed out pamphlets to the hostellers telling them that they too were victims of oppression. A reconciliation of sorts was effected. The ‘backlash’ had back-lashed on the Government. When the next stay-away was called, many hostellers were among its most active supporters.

Leaders of commerce and industry had decided not to pay absentees, irrespective of whether or not they thought that their workers had been intimidated. The president of the Transvall Chamber of Commerce, Ernest Housmann, declared that employers had ‘every sympathy with law-abiding workers who are intimidated, [but] they simply cannot afford to pay absentees’. And Hausmann added that some employers ‘may decide to dismiss employees who have given trouble in the past’. During the first strike a black woman earning R50 a month as a chambermaid in a posh Johannesburg hotel was so determined to get to work that she took two taxis into town and two back to Soweto in the afternoon. That cost her R2 —more than her day’s wages. The proprietor of the hotel refused to reimburse her. ‘Why don’t you bring your children up properly?’ he asked. On the Tuesday night of the strike, as if to compound their hardship, the people of Soweto heard that the price of bread, which was more of a staple food in the townships than in white suburbs, was going up by a quarter.