Originally published on Libcom, Apr 23 2011

An unfinished text, written in 2006 (originally entitled “1981 & All That”), intended to be about the riots of 1981, but only the bit about the uprising in the St.Paul’s district of Bristol was completed.

The introduction gives a flavour of the pessimistic feel of 5 years ago. The last 5 or 6 months since Millbank has changed that, but there’s still a long way to go (and a fairly short time to do it) for the new social movements to re-learn the strengths and weaknesses of past movements in order to go beyond them – and this time without a significantly “definitive” defeat and retreat.

1981 & All That

1981 seems a billion miles from 2006. In 25 years, from being the Wests’ most explosive hotspot, Britain has become, with sporadic and marginal exceptions, a virtual no-go area for the class war. In 25 years the UK decayed from being a breath of fresh air, the class struggle expanding in unforeseen ways, sometimes evermore conscious of itself, to becoming a suffocatingly ever drier, narrower and unprecedentedly ultra-conservative ultra-mad place. A whole generation, schooled on largely uncontested alienations derived from the victory of Monetarism/Money Terrorism, has learnt only how to become as suicidal as capitalism in this world without exit. Almost everyone is forced to lead a normal life and are going loopy in having to try to pursue this normality.

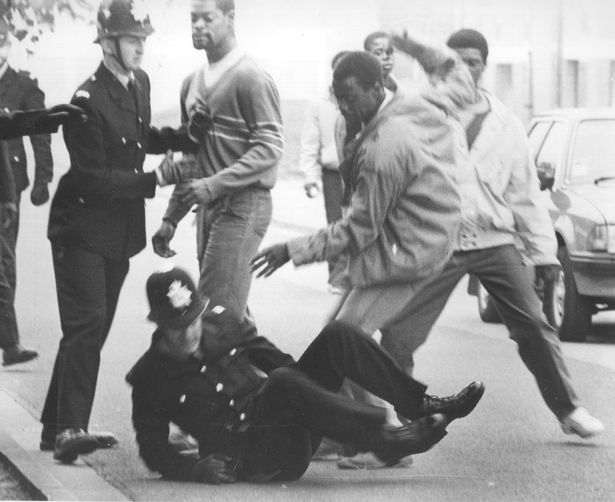

In this totalitarian society that constantly re-writes history just as previous forms of totalitarianism have, the riots of 1981 are presented as “race riots”, like the riots in Burnley, Oldham, Bradford and Leeds. Present history is re-written instantaneously of course. In lumping all the Northern riots in the spring of 2001 together, presenting all of them as race riots when not all of them were, the totalitarian liberal media hoped to incite in the white working class the very racism they pretended to lament. Since the Bradford and Leeds riots were mainly anti-cop riots, with a bit of window shopping thrown in, with more than a handful of whites joining in, they had to be crudely presented, complete with crocodile tears, as race riots in order to reinforce this divide, and to make all riots seem the same inexplicable expression of the nastiness of the human condition.

Likewise the media’s mention of the memory of 1981 is only to claim they were race riots, when the biggest of these riots – in Toxteth, Liverpool – involved a lot more whites than blacks, like virtually all of the riots following Toxteth in July ’81. For the benefit of this generation without history we present this corrective to official history – not out of nostalgia for the tragically sad virtual disappearance of these stumblingly struggling movements against normality but to see what there is in this history we can apply to our understanding of, and struggle against, the present. What we have lost is also what we must re-gain in the very different conditions of the here and now. Our roots are part of us and are part of the fertile means through which we extract the necessary nutrition for our future flowering. But in this sterile world we have to dig deep for them.

For the rest of Europe, many countries now face the kind of restructuring – Thatcherisation, or liberalisation as its now called – that was achieved in the UK 20 years ago. …..

So what happened back in them golden olden days?

“Bristol today – Brixton tomorrow!”

– graffiti, Brixton, 1980

In April 1980, less than a year after Thatcher’s coming to power, a mainly black area of Bristol, St.Paul’s, rose up against the cops. This was just as the steelworkers strike against mass redundancies, the longest steelworkers strike since World War II, was fizzling out, a defeat for the strikers. 11 months after the start of Thatcher’s Blitz, there came a little sparkle of hope – a firework to light up the night of demoralisation, a small taster of explosions to come.

St.Pauls at this time was an area of Bristol with less than a 50% black population, but which was a magnet for many Bristol blacks who didn’t live there – a bit like Notting Hill. A red light district, it was where the street life was, the night and day life, the focus for black social life. In Grosvenor Road the Black and White Café, run by a black and white husband-and-wife team, was its centre. Created from the ground floor of a terraced house, it was the only mainly black café in the area which had not been forced out of business for contravening local authority health regulations or for other bureaucratic reasons. But it had had its licence to sell alcohol removed.

Between 1977 and 1980 unemployment among blacks in Bristol doubled (whereas it declined for whites). So there was a lot of street life during the day – no New Deal crap or computers keeping you stuck indoors, out of trouble. Equally there was no heroin or crack – Rastafarianism, for all its mysogeny and weird illusions in the dead Emperor (“Sieg Hailie!”), was absolutely opposed to heroin – and prevented any heroin dealers moving in at this time. It also had an o.k. ideology of sharing everything which often helped contribute to a friendly atmosphere.

On April 2nd, 39 cops armed with search warrants for drugs and illegal consumption of alcohol moved in, arresting the male owner, taking him away in handcuffs, protesting loudly, to be charged with possessing cannabis and allowing it to be smoked on his premises, whilst they emptied the café of its bottles of brandy, vodka and 132 crates of beer, loading them into a van in front of a growing and increasingly restless crowd outside. As the van with the alcohol left, a bottle was thrown. When the cops tore a man’s trousers and the drugs squad made a run for their car with their booty, there was a shout, “Let’s get the dope, let’s get the drugs squad” and missiles were thrown at the cop car and at the cops. Under a hail of bricks, bottles and stones from the crowd of about 150 black and white youths on the grassy area opposite the café, the cops who were left took refuge in the café, radioing for help. Two hours after the raid had begun, reinforcements arrived, 100 cops assembling down one end of Grosvenor Road hoping to intimidate the crowd with a military-style show of strength – marching “left, right, left, right, like they were on parade. They had dogs with them. When they came in front of the café, we let them have it.”, a black prostitute told the press.

Once the cops in the café had been rescued, there was a lull in the battle. But the State cannot allow no-go areas, so reinforcements had to be called in from outside the immediate area. A couple of cops on their own were attacked with flying objects, their cars turned over by about 12 black youths, one of the cars being set on fire. About 30 cops came under attack as a breakdown van came to take away the burnt-out vehicle. 50 – 60 cops with recently designed, and somewhat cumbersome, riot shields began to move towards about 200 missile throwers, but the bombardment was so intense, they had to move back, cops getting injured, cop cars overturned and set on fire and the crowd starting to loot. Lloyds Bank was attacked, broken into and set on fire. Firemen trying to quench the flames were also attacked. Cops trying to protect the bank were forced to withdraw under ferocious attack. Of the 50 – 60 cops on the scene, 22 had to go to hospital, 27 more had minor injuries, 21 cop cars were severely damaged and 6 were destroyed beyond repair. At the height of the battle there were at least 2000 rioters, a minority of whom were white. The cops decided to withdraw in order to collect reinforcements from neighbouring police forces around Bristol. But for over 3 hours the area was a no-go area for the State and there was massive looting, much of it by whites: about £150,000 worth of goods was nicked from the stores. Rioters were just about to set fire to the local Labour Exchange when a black former employee at the Labour Exchange warned them that if they torched the building they’d lose their weekly giro – a load of crap, of course: the State at this time was on the defensive, and would have been shit-scared of even a few day’s delay in issuing giros…By 11p.m., over 7 hours after the raid had begun, the cops saturated the area and by midnight the State had re-asserted its authority. By no means had this been a race riot – the only whites attacked were the cops, and clearly whites, despite not suffering as much abuse and humiliation from the cops as blacks, had joined in the battle. A third of those arrested were white. One of the blacks who reduced the cause of the riot to racism – “What has to be faced up to is that Britain is deeply racialist” – was Francis Salandy, a Rasta, who’d been consulted about the cop raid 9 days before it happened. The all-embracing generalisation “Britain is deeply racialist” acts as a cover for the fact that he collaborated with the main enforcers of this racism – the State in the form of the police. But then that’s the classic contradiction of all the anti-racist Middle Class, and would-be Middle Class.

16 of those arrested were charged with riotous assembly, carrying a maximum sentence of life imprisonment. The committal proceedings to decide whether there was a case to answer lasted 6 weeks and sometimes involved fighting breaking out in the courtroom between youths and cops. Some of the accused leapt from the dock to join in and there were clashes outside the court between about 100 demonstrators and the cops. Eventually 12 youths were put on trial, 11 of them black, 1 a prostitute mother of 4 kids (who was also charged with maliciously wounding a cop), 5 of them aged just 17. The trial eventually collapsed – with the jury giving 5 outright acquittals and deadlocked on the remaining 7. The failed trial cost half a million pounds – the same cost as riot damage. The ruling society hoped that this would be a one-off riot – and if it wasn’t going to be, they’d make a few preparations. But they didn’t realise how much the marginalised – especially the blacks – were beginning to grow in confidence.

It’s indicative of how much mutual hatred there was between the cops and blacks that in mid-1980 100s of representatives of largely middle class black/Asian organisations, such as the inaptly named Indian Workers Association, called at a meeting in London for all blacks and Asians in Britain to withdraw co-operation from the police. There probably is still a mutual hatred amongst most blacks, but the middle class black organisations nowadays wouldn’t for one split second even dream of breaking off relations with the cops.

On January 18th 1981 a fire in Deptford, South London, almost certainly deliberately started, gutted a family home during a party – 13 blacks died. The cops got heavy with black witnesses, forcing them to tell bullshit stories about a fight in the house. Though an “incendiary device” was found outside the house, the press and the cops reported it as an accident, then tried to ignore it. The blacks organised The Massacre Action Committee which in turn initiated a demonstration on March 2nd, a weekday, when 10,000 – mainly blacks – marched from Lewisham, across the Thames, along Fleet Street and into central London. Children skipped school to take part, and others had the day off work. As the march wove up Fleet Street windows were smashed and shops, including a jewellers, looted.

Just over a year after Bristol the predicted uprising in Brixton happened, but when history is made predictions turn out as insubstantial as a sexual fantasy: the real thing is something else.

In the few days up until Friday 10th April, Brixton had been the target of a saturation point cop stop and search plan called “Operation Swamp”. Private Eye later called it “Operation Sambo-bashing”. Every black guy, and some black women and marginal whites, was getting hassle.

On the Friday, a black guy, having been stabbed in some fight or other that nobody knew anything about, tried to avoid being helped by the cops – for the obvious reason that they would want to interview him later. The crowd of blacks misunderstood the situation a bit – one shouted “They’re killing him” – and released him from the cops trying to tend his wounds in order to put him in a passing car to take him to hospital.

This fairly minor incident was the catalyst for two days of what up until then was the U.K.’s most explosive violently anti-State rioting of the 20th century.

(text incomplete)

Originally published on Libcom, Apr 23 2011

Followed by these comments by me:

A friend, admitting to being pedantic, claimed the graffiti in Brixton a few months after the Bristol riot, was not “Bristol today, Brixton tomorrow” but ‘Bristol yesterday, Brixton today!’, adding “It would fit in more with the immediatist impulse ascribed (once) to anarchists than the ‘let’s wait till tomorrow’, ‘hope is the leash of submission’ implied by ‘Brixton tomorrow’.” Maybe – can’t remember. He also reminded me that that bit of graffiti was denounced in one of the Sunday colour supplements (I seem to remember The Observer) by none other than Jamaica’s pet poet laureate (well, winner of “a silver Musgrave medal from the Institute of Jamaica for distinguished eminence in the field of poetry” as Wikipedia puts it) – Linton Kwesi Johnson, who contemptuously denounced the slogan just a few weeks before the uprising in Brixton as something written by”white anarchists”. This was at the time when 121 Railton Road in Brixton was an anarchist squatted bookshop and clearly he felt the need to represent the blacks, present them as special victims of the racist cops without the need for whites (particularly anarchists), also victims of cop brutality, expressing some desire for a breakdown of racial separations.

see also youtube video

Hits as of 15/9/17: 1548

Leave a Reply