This is taken from “cop-out – the significance of Aufhebengate” (2012).

Many people have said that this is the best section of the text. It’s not hard to understand even to those who are unfamiliar with “Aufhebengate”, as it extracts general attitudes applicable to other situations, even if “Aufhebengate” was the specific event that stimulated me to develop the ideas in this text (some of which have been plagiarised from other people in other contexts). It seems worth putting it up as a separate text.

or

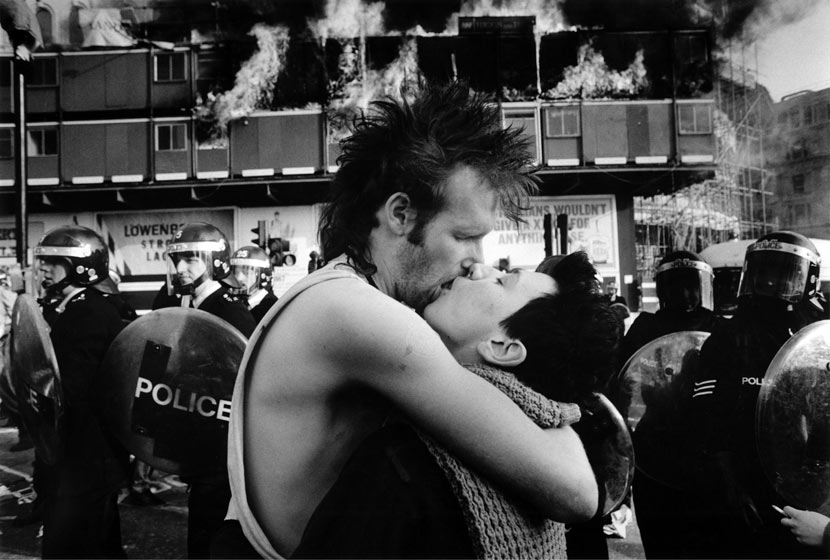

or  Poll tax riot 1990, London, Trafalgar Square

Poll tax riot 1990, London, Trafalgar Square

Stanley cup riot, Vancouver , 2011

Stanley cup riot, Vancouver , 2011

FRAYED THREADS OF FRIENDSHIP

“Opposition is true friendship” – William Blake

Many of those who supported JD, from Aufheben to Libcom and beyond, did so because he was their friend. Yet, in the complex dialectic of subjective choice and objectively determined circumstances, it is as essential to unravel the contradictions of friendship as all the other aspects of life. History is not simply an external force we have to intervene in. Friendship, the area of life most dominated by individual choice, is also affected by history, by the ebb and flow of class struggle.

1

Just as we cannot understand the world unless we try to change it, so we cannot seriously understand our friendships unless we try to transform them. Clarity begins at home.

2

In many ways the dominant relationships of this society continue in part because of varying degrees of the complex web of toleration for what is termed “friendship”. This society is maintained as much by the repressions involved in traditional friendship as it is by political identification or identification with the Nation, particularly as friendship functions at a far more personal, less objectively defined, level than nationalist or traditional politically organised substitutes for genuine community. Equally, opposition to this world will never develop unless friendship becomes inseparable from solidarity. Anti-politics and affection must combine. Solidarity begins at home.

There are two sides to this separation. It’s clear, for instance, that in many anarchist or ultra-leftist organisations daily life is reduced to something you get down to after the meeting is over. Such political organisations inevitably develop a functionalising of people as mere members and the members gladly take on this role. For most, the separation of means and ends and the rivalrous/complicitous mentality is pursued spontaneously with a “what else can you do?” shrug. Shortly after the fall of the Berlin Wall, a Berlin ultra-leftist, after asking if we were there to have a drink and a chat or if we were there to discuss politics, admitted, after a couple of pints, that he felt that sometimes being into politics was like being a businessman. But over twenty years of counter-revolution later, the dominant separation of intellect from the emotions, analysis and critique from the positive and negative poles of feeling (love, friendship, respect and affection; hate, anger, contempt and disgust) are not even conceived as a problematic terrain of struggle for most of the ultra-left 1

The other side of this separation, though is traditional friendship. Traditional friendship bases itself on the ideology of “friendship above politics”. Insofar as this is a refusal of the racket mentality that pits political gang against political gang, this has all the appearance of being an improvement. Traditional friendships generally are less pretentious than political relationships. They involve a minimum of generosity, mutual concern in adversity, and a desire to enjoy each other’s company as far as possible. But some of their limitations are a lack of critique of anything outside the immediate and often a sentimental attitude based on what you had in common in the past, but less and less in the present. What’s more, often this “friendship” is as subject to the gang mentality as politics is. Often it’s a question of one friendship network against another, and of the habitual avoidance of questioning significant contradictions amongst one’s friends, particularly when this friendship avoids expressing itself in acts of solidarity with those struggling to confront concrete expressions of complicity with this society.

In reality, of course, these “two sides” often overlap in some way – but for the purposes of trying to unravel different elements of these “types” of friendship, it has been necessary to look at them as two distinct “forms”.

3

In uprisings people go beyond their particular scenes, break up with some of the people from before, meet and connect to individuals and groups from different scenes and a new fluid world opens up. Then, after the retreat or successful repression of an uprising, the old relationships, from couple to political organisation, can seem insufferable and artificial, their separations and obvious narrowness all too cardboard. So some then either try to supersede these habitual relationships by critique and experiment insofar as these are possible. Or they fall into the depression and/or boredom and/or narrowly easy pleasure-seeking that comes from the sense of defeat and betrayal, arising from experiencing the open air of freedom and being shoved back between the grey walls of old habits and a life going nowhere.

4

“.. all the good times that I’ve wasted having good times” – The Animals 2

The need to have “a good time” defined within the acceptable limits of resigned forms of hedonism is as subject to history as anything else. As a friend from the USA wrote recently, “Oakland seems to be in sort of a rough state right now. I encountered a few of my friends being a little bit more into drugs and partying than I felt comfortable with, which was hard to see. I think things are collapsing a bit there, maybe now that there isn’t as much conflict in the streets people are looking for that buzz elsewhere…”. Struggle unrenewed tends towards this kind of desperate pleasure, which is never pleasurable enough.

In this opening scene of the old 1960 movie, “Saturday night and Sunday morning” 3 the main character, played by Albert Finney, says as the week’s final work shift comes to an end before the weekend: “I’d like to see anybody grind me down – that’d be the day. What I’m out for is a good time. All the rest is propaganda.” Nowadays people are ground down far worse than during the 60s, and one of the reasons people avoid arguing about significant social matters, particularly those that lie closest to home, is that they’re just out to have a good time after the stresses of work and other externally-imposed miseries. It’s not just propaganda they reject, but also critique, which they consider a cold distraction from having a good time. But critical ideas one has developed oneself through trial and error, through struggle and reflection on struggles, in fact can only develop partly by opposing the manipulations of propaganda (whether obviously capitalist or, apparently, anti-capitalist) but also by opposing significant forms of complicity with this society. At the same time, the rejection of propaganda (whether in the form of the dominant dogmas coming from the commodity economy, ‘oppositional’ ideology which reforms this or just simply malicious gossip) obviously recognises that the rejection of critique is not the way to reject manipulation, and insures that these conventional “good times” get worse and worse, increasingly frustrated by social constraints the more they are not the result of opposing such restraints. Everyone wants an easy life, but finding it is not at all easy. Consequently these “good times” involve an increasingly desperate attempt to immerse onself in the immediate without critical distance, an immediate of ever more devastating drugs, drink, culture (popular or “sophisticated”) and other religions. Though the desire for life which asserts itself in practical-critical activity is a source of joy, often fun, absorbing, meaningful, exhilirating and funny, it is also necessary to launch battles which are not always the cause, or even the aim, of the immediate pleasures that far too many people seek to consume. Nowadays, almost anybody who tries to argue over significant contradictions is regarded as a killjoy, and certainly someone who takes themselves far too seriously. It is not that people are necessarily against having a good argument, but they only look for arguments that remain at the most “objective” level, abstracted from any particular contradiction of the person one is having an argument with, and particularly one that requires absolutely no practical decision on the part of the arguers whatsoever. Anybody who stirs up emotional and personal tension in an argument, particularly when some kind of action is shown to be vital, is regarded as a pain-in-the-arse, and not invited to the next dinner party.

5

“Having feelings of affection in regard to other people is not contradictory in itself with maintaining an individual point of view – true affection can only exist where there is individual affirmation, except when these feelings serve as justification for a person to abandon their point of view. I define affective relations as those relations justified by “affection”, which can only maintain themselves on the basis of repression.

Pseudo-affection, which serves as justification for self-betrayal, must itself be justified – to give a coherent appearance to this very betrayal – with objective qualities, be they real or imaginary, encountered in the people who are the objects of pseudo-affection. But in so doing, the affective individual reveals that they aspire to be loved for their “objective” intrinsic qualities, even though they do not know how to put them to use for themselves – and thus these qualities do not exist – any more than they know how to recognise, through practice, the qualities of their friends. Having…renounced critique, they demand that others reciprocate, that they leave them alone, that they accept them as they are. What is to be found here is…the old mystico-bourgeois conception of the “interior richness of the human being, always there to be discovered”, which would have it that a person is something other than what they actually do.”

-

Nadine Bloch, ‘All Things Considered, 1976’.

6

From the late 1970s onwards we have seen the development of enormous amounts of proletarians who thankfully no longer play any arrogant, verbose or rigid rôle. Unfortunately they also don’t put themselves in any serious opposition to this society or to the powers-that-be, particularly when ideological pro-state or pro-market comportment expresses itself in their own friendships. Here we see the development of the “anti-role” amongst individuals which, whilst often paying lip-service to “anti-capitalist” verbiage, says or does nothing that might upset the equilibrium of their conservative social relationships. Humility has replaced arrogance. If the false self-importance of the “arrogant” comes from the illusion of being significant despite the paucity of the social effect of their ideas, as well as their inability to empathise, the excessively “humble” regard their point of view as being so insignificant they’ve decided that expressing and arming it is being over-serious, too self-important and pretentious.

In a meaningless world, to struggle for a rational passionate society is considered as having an unrealisticly inordinate sense of purpose. Whilst the still-present hangovers of post-modernism continue to try to valorise present meaninglessness as realisticaly unideological, such flaccid resignation is becoming all-too obviously complicitous with the intensifying horrors of an intensifying crisis-ridden class society. Yet, despite the obvious, the feeling that nothing can be done becomes an excuse for not even taking the first step. After all, it’s just one measly step and not worth the bother. Here “critique” of the obvious limits of “first steps” is not intended to lead to any personal proof of something better, but just as an articulate excuse to not do anything even as good. The negative petrified into negativism. The demoralised always have to sneeringly reduce those trying to do something to their own demoralised level because they cannot stand anything that reminds them of their own inertia and need to pretend that everyone else is the same. Here humility and arrogance combine in an aggressive display of impotence. What the humble arrogantly demand is to become as inconsequential as they are. And it is you that gets accused of arrogance for changing, however minimally, a situation that they have stubbornly resisted changing. “Failure to transform oneself and to transform society is jabbered away in the public expression of a powerless consciousness. This is everywhere acclaimed, acknowledged as the mark of sophistication …Beyond the aestheticized folderol, the choice is simple: you either submit to your “fate” or undercut in practice the objective bases of your own participation in what makes you a perennial loser.” – Chris Shutes, “Two Local Chapters In The Spectacle of Decomposition” 4.

7

Over 20 years of serious counter-revolution have fretted and frayed the fragile threads of friendship, and inseparably the fragile sense of self, in such a way that people tend more and more to desperately latch onto any “community” just to feel they exist.

In the UK, this repressed subjectivity has been compounded enormously since the early 1990s when one could say that the last national crisis of class society (the poll tax riots) hit the streets, only to have such crises assuming an increasingly marginal aspect up until the attack on Millbank in 0ctober 2010. This profound weakening of individuals’ ability to contest this society brought about by the counter-revolution has infected “revolutionaries” as much as anybody else, surprise surprise. A kind of indifferent relativism reigns, an eclecticism in which all conflicting perspectives are reduced to a post-modernist equivalence. Anyone who considers something as vital, is thought of as getting on their moral highhorse and clearly compensating for some other misery.

Certain geographical areas in which isolation is particularly acute, particularly those where there is very little community of struggle, contribute towards this “any friendship is better than taking a calculated risk with friendships”. Whilst boasting about the sexual “conquests” one has notched up is considered a little shabby, sad and definitely archaic, this is not the case with friends. Hence all those Facebook pages with a large list of friends you try to impress the world with how much you’re liked (often, particularly with teenagers, this includes people you’ve only met once whilst drunk at a party). To hide our isolation we have to make a show of these numbers: not only does quantity takes precedent over quality, but the show of friendship hides its superficiality, the avoidance of trying to go beyond its limits.

In the UK I know people who are friendly with an ex-Class War guy who, publicly on the internet, advocates, using a semi-anarchist self-management ideology, an entirely nationalist attitude towards immigration control because that’s what the (UK) working class wants (this at a time when various pseudo-anti-capitalist nationalist “solutions” to the crisis could lead to some form of fascism). He is tolerated because he’s a “nice guy”, a justification which ignores the very nasty politics he advocates (in fact, over a hundred years ago, Irish immigration to the UK was also opposed, in a racist manner, because of its undercutting of English workers’ wages – Keir Hardie was one of the more public advocates of this nationalist perspective).

But this is not at all confined to the UK. An absurd example of this pushed to extremes is a story I recently heard of Australian anarchists who, when it was discovered that one of them was an undercover cop, declared “But he’s a nice guy”. As if this hadn’t caused these anarchists to have a crisis over their notion of what “nice” meant. Judgement on the very superficial considerations of someone’s personality and image, the criteria by which increasing millions of proletarians are accepted or rejected for many different types of wage labour, is increasingly applied to personal relations as well. But the shallowness of such criteria are rarely tested, because, if challenged in any significant way helpful to subverting the nasty world we live in, one can find behind many a nice persona a very unpleasant attitude, utterly complicit with the viciousness of capital (and not just amongst undercover cops). Such superficial judgement is a mark of how enormously weakened the working class has become.

Ignoring (in any practical sense) someone’s sick behaviour because they are “nice” is often a reflection of one’s desire to be accepted and liked for your own resigned self as long as you put on a smile. In a fundamentally schizoid world, this toleration and desire to be tolerated for ones’ resigned self is bought at the cost of a fundamental self-betrayal. People have become so neurotically unconfident about asserting themselves and upsetting people that they almost sound like those teenagers of the last 20 years or more who make every sentence, even the least controversial, sound like some tentative question for fear of sounding too strident. The desire for popularity, the tendency towards a need to be liked above all other considerations, expresses a deep-seated terror of recognising the reality of separations and even more so of trying to overcome them. In a world of strangers, those who strive to take off the socially acceptable masks are considered strange. In the UK more than anywhere….As people’s lives have become increasingly precarious, so their sense of self has also become increasingly precarious. And avoiding confronting the material base of this fragility also involves avoiding trying to subvert frustrations in friendships, and avoiding activity which could overcome such frustrations. This intensified fragility means that everytime a significant contradiction arises in friendships, instead of making an irreversible demand on the friend to not continue doing what’s seriously pissing you off in their repetitive behaviour or proposing a project that could challenge the contradiction, a compromised avoidance of a break with the past is reached and the tension is repressed until the same old contradiction surfaces again and the whole tension is repeated. Or else a break happens without explanation and so the social consequences for such a friendship network is also avoided. These vicious circles must be broken (and some of these circles of friends can be very vicious).

The contradictions of traditional friendships accumulated over these past 20 years or so of counter-revolution niggle like a disconcerting dream on the brains and bodies of living relationships. In the previous epoch of restless sleep into which proletarians have settled, the sentimental attitude in friendships based in the past and in habit, even those born out of struggle, have become, for many, reduced to the minimum give and take without much exigency at all, other than a vaguely oppositional verbiage. But in the current epoch, where clearly a brutal future awaits us, the traditions of “any friendship is better than none” function as a brake on the need to advance a desperately felt opposition to the accelerating runaway train of the rulers’ economy. We must demand more than this bare minimum if friendship is to mean solidarity. And strive to clarify what such solidarity concretely means.

In this unexperimental retreat, there are many who have adopted a spectacle of opposition as complacent as all the other pseudo-communities. “Polite society”, based on not speaking your mind, has so invaded daily life that even those claiming to oppose it avoid the slightest awkwardness of significant critique, let alone consequential critique. In fact, those who apparently oppose this society actually often seem more afflicted by the self-satisfaction constantly generated by it than those who haven’t developed the smokescreen of “critique”. Their identity as rebels lets them believe that purely by holding this identity are they actually doing something to undermine their complicity with this society. That by consuming &/or adopting and mouthing a set of beliefs and routines they can feel safe within the category “rebel”/”communist”/anarchist/Marxist/whateverist. There are some who are clearly intellectually (but not practically) adept at bringing new light onto the more objective aspects of the new forms of alienation, but remain merely theoretically innovative, a bit like the Frankfurt school in its time, even if a more proletarian class conscious version. But they have forgotten those past moments when they expressed genuine dissatisfaction directly, made a decision that challenged their equilibrium and that of dominant social relations a little, took some angry initiative, used their insights consequentially, and demanded the support and encouragement of their friends. Here, a community of “intellectual” critique proves itself to be as tenuous a link between individuals as that between individuals in “communities” based on taste and hobbies, yet even more self–contradictory since it claims to be confronting social misery. The counter-revolution has meant a repressed reversion to traditional “friendship”. And when there are split loyalties, usually those in the middle choose to avoid the discomfort of either taking sides or of ”making sides” by openly stating their differences with both sides, for fear of a consequence they feel they can’t control. That is, they remain to all intents and purposes, passive and silent, only having the intent and purpose of sitting on the fence, staying ‘friends’ with everybody and dismissive of any attempt to persuade them to make a stand as pushy and “alienating”. Friendship discovered by making some stand and joining others who do so has been forgotten, and yet in this epoch, with so much at stake, it is this, this elemental solidarity, that will have to become the norm if the struggle to defeat the terrors to come has any chance of making progress.

8

It is in this accepted atmosphere of merely going through the motions of contestation that making our disgust for Aufheben and its defenders public had to be obstructed, resisted and opposed with endless bullshit obstacles, even by some of those who also felt disgust. To make this public (essential if you were serious about making sure that this kind of recuperative rip-off never happens again and that people on demonstrations could make an informed decision about whether they wanted to have a crowd psychologist next to them) challenged everyone’s “Let’s not look at our own indifference and cowardice, politics as normal” mentality. And in the UK this routine “community” just wants to get on; ok, some political ganging up, siding with this clique or organisation against another, or against some individual, but nothing more than sectarian political bickering, or psychologistic criticism, and often private and inconsequential. Everyone in this scene is connected to everyone else, if only by the friendship network. So being public about such contradictions had to be resisted not just with lies but also fake humanist concern. For these people, all those thousands directly affected by the ideological application of the crowd psychology team’s divide and rule tactics were just abstract people “out there”; what mattered were the people or individual (JD) they personally knew.

9

In the 70s amongst some sections of what at that time was some kind of revolutionary milieu, when people had a conflict with friends that also became something significant for the other people who knew them, this conflict was made public to the people concerned (in fact, to a certain extent, this is still the case with some people, though hardly at all in the UK). Curiosity about immediate concrete problems were partly the basis for developing a wider social curiosity. Nowadays, there’s an attitude that “my conflict is my conflict, your conflicts are your conflicts and it’s entirely our own separate business”; yet, though certainly this is not to suggest people take sides necessarily (they could equally take a 3rd or whatever position, in other words, to make sides), it seems that significant arguments are also indicative of wider contradictions and it’s part of the retreat into abstraction, into individualism and into a separate ideological notion of “autonomy” that what is in fact social has become separately, privately “individual”.

10

While modern capitalism manufactures en masse the need for consoling illusion, above all the need for the illusion of community, those who identify with, and try to contribute to, an opposition to capitalism rightly recognise themselves in a genuine community of struggle with all its various contradictions. However, the shattering of marginal areas of life partly free from and resistant to the economy has made more and more shattered individuals identify with a gang, a milieu, a clique, a political organisation or a commune as their safe illusion of community, their often fantasy, sometimes genuine, protection from the cold winds of capital. For many of those who hope to contribute to the class war, instead of organising particular activities as part of their mediation between them and history, they identify with a particular scene or organisation, which mediates their relation to the global community of struggle. This replaces the traditional family with an alternative one. But as with traditional families, familiarity breeds a mix of contempt and respect (respect for a person’s acts, not simply blindly hierarchical, mixed with the contempt that comes from people not being honest or assertive). Everyone with any healthy instinct develops networks of friendship that involve more respect than contempt, and so give some kind of stability in an unstable world. But unless such friendships develop a constant self-questioning as well as affection, and a questioning that leads to activity and decisions, they become increasingly a spiral downwards of more contempt than respect. As petrified as the traditional hierarchical family they hope is a thing of the past. Loyalty to these habitual friendships overrides loyalty to the desire to liberate oneself, inseparable from the desire to contribute to the liberation of humanity. Some of these friendship scenes develop a kind of corporatism, in which loyalty involves the underlying threat: if you dare step out of line, we will gang up against you, and humiliate you, and you will be sacked/ostracised. Loyalty is a fine thing, a basic expression of solidarity. But when it expresses itself as loyalty to ‘friends’ who have clearly manifested a betrayal of perspectives that have formed a basic part of the friendship, it becomes a form of masochism, the kind of self betrayal that niggles and wears you down for the rest of your life unless you express yourself in such a way that breaks with such a submissive loyalty. Which is not to say that there are any quick solutions to this split loyalty conflict.

The gang mentality most often manifests itself in the way people change friends with the wind: if the family/clique oppose the person where once they liked them, then the individual has to choose between having some integrity of independence whilst feeling their way around a complex situation or silently going along with the most articulate view of the people in their scene. Affection is abandoned too quickly, too easy to be genuine. It takes time, tears, questions, patience…before ones patience runs out.

The enormous intensification of the individualist mentality brought about by the repression and marginalisation of communities of struggle over the last 20 years or more, has, seemingly paradoxically, also had the effect of reinforcing all the “collectivities” (from the nation to the traditional couple, from the clique to NGOs) which seem like some exit from bourgeois individualism. But as the proletariat starts to resurface and once again strives to seize the stage of history, the false conflict between individualism and collectivism also seems to intensify and functions as an even more complex force repressing the struggle for a community of mutual recognition. In this context, Aufhebengate revealed the “loyal” attachments of those collectivists who supported Aufheben – a kind of blind faith in their friends (like faith in God or the State, it was not tested by open practical questioning). At the same time, it revealed the indifferent individualism of those who kept quiet about their misgivings, those who considered such a contradiction to be a private individual affair, and maintained their (largely secret) critiques of Aufheben without considering any public decision had to be made. In both cases (collectivist self-repression, and individualist self-repression) the desire to avoid any progress or upset was necessary to maintain a fixed notion of an incontestable reality.

11

In mid-October 2011 ocelot, a regular contributor to Libcom, wrote about Aufhebengate: “The underlying issue here is the tendency of people who elaborate sophisticated politics in “peacetime” – i.e. in conditions free from any stress – to revert to unthinking or opportunistic politics at the first sight of trouble. Given that politics effectively only really matters in whether people make the right decisions or the wrong decisions in the most desperate situations, only “politics under fire” is real politics. In this case, under the relatively minor stress of a perceived online threat to a friend and comrade, people involved in Aufheben and Libcom both, apparently, have come out with some completely untenable politics in their somewhat panicked efforts at defence. If you can’t even hold a proper political line under relatively minor stress, what chance have you got when people really are being killed or jailed forever? Worse still, experience teaches that some people are so lame that rather than admit that some of the things they said under stress, were a mistake and/or politically absurd, they then spend the rest of their days trying to rearrange their political frameworks to retrospectively justify hastily adopted opportunistic positions, forced on them by the contingencies of the moment .”

On the eve of possibly the world’s gravest crisis ever (both economic and ecological, and possibly eventually military) one wonders how those who haven’t the will, nerve or strength to confront an individual helping the state within their midst, or confront those making excuses for him, dare have the pretension to believe they could significantly contribute to subverting the power of the state when it attacks them as an external and far more powerful force.

Poll tax riot 1990, London, Trafalgar Square

Stanley cup riot, Vancouver , 2011

____________________

_________________

“True friends stab you in the front” – Oscar Wilde

__________________________________________________________

There will doubtless be people who will object to this or that as being too superficial, not being fairly balanced or “objective”.

But I have written this from the simple perspective:

“if the shoe fits – wear it.”

(and point it in the right direction)

Footnotes

Please note: 2 of the return links in these footnotes lead back to the original “cop-out…” text, not to this page. To return to where you clicked the number for the footnote, you’ll just have to scroll back upwards or click the return arrow on your browser.

1 A contact wrote, “There’s something about the lingo of the Solfed group which rubs me all wrong. It lacks any emotional substance or grit, it reeks of academics trying really hard to speak like a simple prole. Their brains have been morphed into a cobweb of formulaic abstractions, it’s just so boring and tedious and bureaucratic, it really has no relevance to the world of flesh and blood people, ‘political groups vs. political/economic groups’ and so on. I remember awhile ago reading some of the writing from members of the FAI….whatever we think about the FAI these days, what made that writing stick in my head is that it communicated a degree of passion and despair which you never really see coming from revolutionaries these days. It struck you as people speaking from their hearts. You don’t get this from solfed or from many of these ultra-left communist groups like Aufheben even when their articles are very good in other ways. I’m not sure exactly what that means except that maybe too many people have a largely intellectual attachment to class struggle which is why they’re really bad at communicating what they feel as well as what they think.”.

Please note: the return link on this footnote doesn’t work. To return to where you clicked the number for the footnote, you’ll just have to scroll back upwards or click the return arrow on your browser.

Leave a Reply