Chapter 15:

2nd dockers strike…TUC Brighton Conference…pathetic Leftism…

…niceness and urgency…Contradictions of the NUM….

…More attacks on NCB property and on cops…

…Thatcher almost caves in…IRA bombs Thatcher…

…unpublished leaflet…NACODS and the almost strike…

…MI5’s dirty tricks…Thatcher almost lost…almost almost…

September saw the second national dock strike, called in response to the BSC allowing a coal ship to dock at Hunterston in Ayrshire without TGWU boatmen to moor the ship – they used a local contract firm instead. The union had blacked the ship after talks broke down between them and the BSC over the level of iron and coal supplies to Ravenscraig. In Scotland, dockers responded immediately with solid strikes in all 12 DLS ports. None of the non-DLS ports in England joined at any stage and the situation in the English DLS ports was a complete mess, with dockers either unable to decide whether they were in or out, expressing and ;encouraging serious splits within ports. In Britson, a meeting broke up in confusion after shop stewards refused to allow a vote. At Tilbury, the shop stewards blatantly tried to rig the vote byt means of a confusing resolution which led many dockers to believe they were voting to return to work when in fact they were voting to strike ( a cou;e of days previously 600 dockers had held an unofficial meeting and voted to return to work, but only 40 of the scabs actually dared to cross the picket line.

By the second week there were over half of the DLS dockers (almost 8,000 out of 13,000) out on strike and almost none of the non-DLS dockers. Then John Connolly said that although the strike was over “scab labour”, it could be resolved through lower coke quotas for Ravenscraig. In other words, the question of preserving the Dock Labour Scheme was being quietly shelved once again. During this second week, there were quite a few attempts to picket out the working ports, with Southampton dockers unsuccessfully picketing Felixstowe, Portsmouth and Poole, and by the third week some miners were jioning in the picketing of Grmisby and Immingham (several hundred being turned back by the cops, as were 50 Hull dockers). In the middle of all this the TGWU leadership responded by saying that pickiting must be stepped up providing, of course, that it is within TUC guidelines. The TUC picketing guidelines were drawn up between the TUC and the Callaghan Government after the Winter Of Discontent. Basically, the guidelines said that pickets should act in a “disciplined and peaceful manner”, even when provoked and should obey the instructions of union officials at all times.

By the end of the third week a shabby deal was patched together involving collaboration between union bureaucrats and slimy Labour politicans like John Prescott and Neil Kinnock. At the end of it all, BSC gave nothing away over the employment of non-DLS labour and the union agreed to meet the BSC/ISTC quota of imported coal through Hunterston in Scotland within 2 months. Another great victory!

3/9/84:

In Brighton there was a mass lobby of the TUC by miners and supporters. In different parts of the town there’s graffiti saying T.hatcher’s U.nofficial C.ops.

“We arrived, about 12 of us, men and women, in Brighton after going a round about way to avoid the cops’ possibly turning us back. It’d been an unusually long drive in the van, considering the normal short distance. We parked the Southwark Unemployed Centre van over half a mile from the beach, drank a bit of wine and headed off, mid-morning, towards the sea front for the demonstration, armed with spray cans and pamphlets. There’s a statue of Queen Victoria in the park so two of us went down to the statue and one gets up high to shove a black flag in her hand, whilst the other one at the bottom spray-paints, “We are all abused”. Cops come along and, without radioing for back-up, attempted to arrest him, holding him in an arm lock from the front round his neck and at the side. The others came along and one of them bit one cops hand, whilst others pushed the other cop out of the way, and the guy ran like fuck through the narrow streets and everybody else did likewise – everyone gets away. As soon as the spray-painter meets up with one of his mates, she gives him her jumper so he looks different, whilst the cops go round Brighton peering out of their cop car in vain all round the demo for the crowd who assaulted them. No one gets nicked, and we continue the day in good spirits, elated by this small victory, handing out subversive pamphlets and chatting and arguing and feeling good, whilst most other people felt pretty bored.” At the time, this seemed to be the only incident of the day, the rest of the lobby being utterly peaceful, whilst the TUC leaders bent over backwards to praise the miners all the better to bury them – basically to avoid any conflict which would show up their utterly repressive function. Like bosses and leaders everywhere, they were full of promises – which meant zilch. But, it seemed like a successful method of pacifying the miners, who’d been threatening for days, weeks, months even, to get angry with the TUC: according to the papers, the whole day passed peacefully.

A letter was later sent to one of those involved in the incident mentioned above:

“Dear G.,

I have been asked to write to you about the incident involving you, some of your friends and the police at Brighton on the TUC lobby on Sept.3rd.

Whilst it is obviously no concern of ours how individuals behave in their own time, a number of those attending the lobby and several Miners Support Group members who did not expressed their feelings that it was frankly out of order for people representing the MSG and therefore the NUM as a whole to behave in such a way that could bring the miners and their supporters into disrepute. We spoke to a number of Kent miners whom the MSG is supporting and they have echoed our sentiments.

At last Monday’s meeting of the MSG (10/9/84) it was therefore suggested that we write to you expressing our concern over the matter and requesting you to inform your friends that, should they wish to attend future lobbies, demonstrations etc. organised by us they must refrain from acting in the way they did previously or else exempt themselves from the right to attend such events in our name and using our transport.

Yours fraternally,

N.Phillips,

for and on behalf of Southwark Unemployed Centre Miners Support Group.

Sheer poetry. Especially the bit about “how individuals behave in their own time” – if only we’d realised this was work-time, we could have demanded a wage for the day. Or perhaps we weren’t meant to be wage-slaves at all, simply slaves.

But what a laughably pompous bureaucratic representation of outraged reasonableness! What’s sadly sad behind this joke is that there was too much of this crass conservative desire to represent, and demand that everyone represent, a ‘reasonable’ moral goody goody image amongst the Left and the liberal supporters of the miners which miners failed to oppose.

There was a more interesting incident the day of the TUC lobby deserving of mention which would have shocked the above quoted N. Phillips into writing an even sterner letter and maybe wag his forefinger till it dropped off – if he’d heard about it: several union leaders cars had been attacked and smashed in the evening in a car park near the TUC conference – but it was mostly kept quiet to give the image of sweet harmony. People only heard about it some time after. This ability of the ruling world to keep secrets until their revelation has no practical use is something that any future movement will have to find ways of attacking – not just by creating informative information nextworks (like the regular monthly, sometimes, weekly, journal produced during the Wapping dispute – “Picket”) but also finding ways of uncovering the seemingly invincible manipulations of the State’s secret services – but more of this later.

Let’s continue the point above where we said, “… there was too much of this crass conservative desire to represent, and demand that everyone represent, a ‘reasonable’ moral goody goody image amongst the Left and the liberal supporters of the miners which miners failed to oppose.” This was probably because it would have seemed too much like ungratefully biting the hand that feeds them. They were grateful for any support they could get, and held back on any criticism of patronising attitudes or ‘correct’ line-pushing. The desire to just get on, to be ‘nice’, can often repress the most fundamental things, particularly in a struggle as vital as this. Too often those fighting this fight confined their criticisms to behind people’s backs. A Fitzwilliam miner’s wife said towards the end of the strike, “I didn’t mind the lefties at first. Then I realised they just wanted to manipulate us.”

In fact, on both sides – miners and even their most radical supporters – there was a tendency to hold back what you really thought. Those supporters who were critical of the NUM and of Scargill voiced their critiques fairly mutedly – holding back on any sense of urgency in trying to find some way of going beyond and subverting the union. This was partly because they felt kind of grateful that they could come along and help out the struggle, grateful for the generous warmth and spirit, grateful that the miners were open to support as compared with a more corporatist mentality – “we’ll fight and win our fight on our own – we don’t need outsiders” – from the pre-Thatcher epoch (a mentality which, in its own terms, was true: workers often did win without connecting to ‘outsiders’ because there was already a general rising confidence to struggle and because the State hadn’t yet found a way to divide and rule so well).

The path of least resistance is paved with good intentions and we know where that road leads to.

Nowadays people’s sense of self and of each other is so fragile that niceness seems like the only essential thing in life and the slightest expressed frustration leads to an explosion of variations on “You’re not being nice to me!!”. Arguing having less and less connection to a social struggle against hierarchy, avoiding arguments seems like the only way to be.

But at that time arguing about what to do to extend the struggle for ‘outsiders’ should not have contradicted the desire to get on on a friendly basis. Which was why it was a shame we didn’t express ourselves better. Perhaps this was just a fear of falling into the role of arrogantly trying to teach the workers lessons. Whilst everyone could agree about the media and Kinnock and the cops, arguments about the union were far too often avoided, or limited to light chat. This isn’t a plea for the virtues of getting heavy, like some people play the challenger role – but over time, it was very important to do something about the union – not just chat…In part, however, this was due to the surprise that the union wasn’t exactly like other unions…For some, this meant completely dropping their critique of unions (or at least of the NUM) – a cowardice justified with a Leninist-political mentality of trying to be popular above all, the place where ‘niceness’ and opportunism meet [11]. Whilst others just didn’t want to analyse the subtleties of the contradictions of the NUM, falling back on an oversimplified critique from a distance. They condemned the NUM as being like other unions, looking mainly at unionism as a generality and in terms of its most well known full-time leaders but not at the daily life of the NUM in the villages. Unlike most unions and industries, its members were still living as a community in the locality of their workplace, a kind of “throwback” giving them an unusual cohesion and solidarity (the absence and/or disappearance of this in other industries has certainly affected and weakened work-based struggles). The hit squads were the living evidence of an autonomous self-organised struggle which also usually involved the local union leaders, and union equipment and local union financing – although it should be emphasised that union officials contributed no more than any other striker. In fact, the union was seen as being a lot less separate from the strikers and from the wider community than in other (non-miners) strikes. Ultra-leftists and others were right to point out the times when the NUM clearly did act as something against the strikers (e.g. when in Fitzwilliam, the NUM withdrew its mini-bus, enormously limiting locallly controlled action) but tended to exaggerate them and ignore the aspects of how the NUM were also intertwined with independent struggle. At the top it was partly an old vanguardist project of developing a State capitalism tied to industrial capital, but at the bottom it was a hell of a lot more blurred. Without wishing to minimise some of the hierarchical aspects of the NUM at local level, there was a difference between the national NUM and the local NUM. Of course, NUM ideologists ignored the aspects of the NUM which contradicted their notion that there was no difference between the union and independent struggle, that it was nothing more than the autonomous power of its members, that the Union was its members. They see no critique, hear no critique, speak no critique. Simple. Fitzwilliam strikers were far more critical of the national leadership, which may have been one of the reasons why the NUM withdrew its minibus in the last couple of months of the strike. The reason for their dislike of Scargill was straightforward. Kinsley, the Fitzwilliam pit, was originally a deep mine, which closed, leaving all the Fitzwilliam miners having to get jobs in pits miles away. Then some years later, it re-opened as a drift mine – Kinsley Drift. The miners from Fitzwilliam wanted their jobs back, but Scargill helped to stitch them up by getting the miners from his own pit jobs there. The fact that Fitzwilliam miners didn’t work at Kinsley was significant during the strike because the miners at Kinsley (and therefore in the local NUM branch) were far less militant that the Fitzwilliamers, and they weren’t part of the community, nor did they have any stake in it.

* * * * * * * * * * * *

3/9/84: 2 molotovs are chucked at the electrical substation near Kiveton Park colliery as 7 miners went back to work. Later on in the strike (no date, but well before Christmas) a TV programme showed the dispute between scabs and pickets in the area by reducing this to two personalities (the leading scab and the local NUM branch official). Up till Christmas there were something like 15 scabs in Kiveton out of a total workforce of almost a thousand, but the TV gave equal time to the leading scab and his wife and the branch offical. The scab was portrayed as reasonable. This is known as ‘balance’. Just how balanced the scab was is shown by the fact that after the strike he went to his local bank and demanded to see his bank balance, his savings. When the manager showed him the credit print-out, he said he didn’t want to see it on paper he wanted to see the actual amount of cash he had saved, in notes and coins to make sure the bank actually had his money.

4/9/84:

16 members of management and lower management of the Edinburgh Destroyer and of an off-shore platform near Cammell Laird shipyards, Birkenhead, try to get on board the ship which had been occupied for 11 weeks by just 50 boilermakers protesting against redundancies. Immediately, having been alerted by the unemployed centre in Birkenhead, 200 people, among them many miners, arrived quickly and chased them off.

12 unemployed members of Clydeside Anarchist Group stormed a multi-storey office block in Glasgow and occupied the 13th floor office h.q. of the Price Waterhouse millionnaire accountancy firm responsible for sequestrating the South Wales’ miners funds. 2 60 foot banners were stretched around the outside of the block, reading, “Glasgow Backs The Miners” and “Unemployed Solidarity”. 1000s of leaflets explaining the action were handed out at job centres and dole offices throughout the city. The 12 were arrested by the cops, strip-searched and charged with breach of the peace and malicious damage.

September saw the 2nd national dock strike, which was a defeat – it didn’t even achieve the “promise” “won” by the first strike. It wasn’t a sign of growing docker’s solidarity with the miners, even if there were postive moments such as joint dockers’ and miners’ pickets (as there were in the first strike) – it wasn’t even the usual story of growing discontent forcing the union to make the strike official. In the end the TGWU virtually allowed the bosses to ship in any amount of imported coal they wanted through Hunterston in Scotland (which was the origin of the strike). Both unions and bosses claimed a victory, and that they had conceded nothing.

6/9/84:

9 cops and 4 pickets injured as 3000 pickets gather outside Kellingley coliery in North Yorks. The nearby A615 is closed for a time. An ITN crew’s Volvo Estate, parked near the Nottingley miners’ welfare centre, is turned over, partially set on fire and its tyres slashed. Film equipment worth more than £10,000 is taken from the car and strewn across the road. Council workers from the road department of S. Yorks. county council went on strike and joined the miners pickets after 3 of them had been threatened by cops when they were searched in a particularly rough way. In Kiveton Park, 3000 pickets gathered to prevent 7 scabs from entering: the village was under total occupation of the cops, with cops giving V signs to miners’ kids as young as 8 for no particular reason, openly urinating in front of pickets and their families, charging through parts of the village on horseback and beating people up. Seizing the opportunity given by the concentration of police forces at Kiveton

Park, 3000 pickets gathered to prevent 7 scabs from entering: the village was under total occupation of the cops, with cops giving V signs to miners’ kids as young as 8 for no particular reason, openly urinating in front of pickets and their families, charging through parts of the village on horseback and beating people up. Seizing the opportunity given by the concentration of police forces at Kiveton, the people of Edlington attacked scabs’ houses and the few cops remaining there were injured.

24/9/84:

Over 4000 pickets occupy Maltby where there are a couple of scabs and bombard the cops, several of whom are injured.

During August and September, every single local coal board had its reports of sabotage. The Sunday Times moaned, “it is the thousands of cases of minor damage that may in the end prove more costly than the spectacular vandalism”.

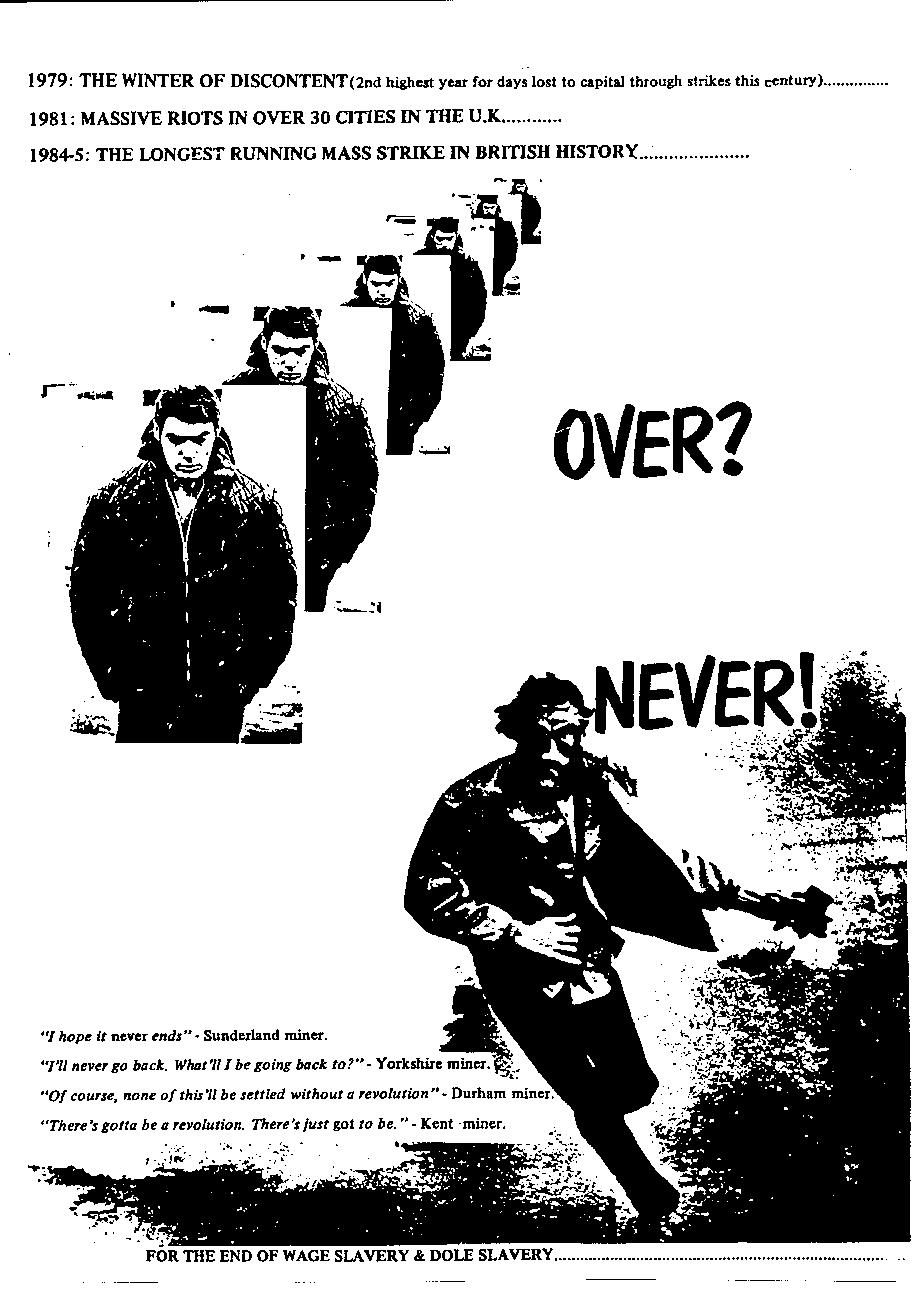

Incomplete and unpublished leaflet written at this time:

The fundamental lie of all the current false choices of submissive life is to scream out at you, 24-hours a day, from the billboards, the radio, the TV, the newspapers, from the teachers and social workers, from shop windows and from the city’s architecture, from every nook and cranny of colonized space, that your anger, your desires, your point of view are all nothing, unrealistic, impossible. If you don’t resign yourself to the ‘realistic’ inevitability of cops, schools, money, hypocrisy, mass starvation, wage labour, buying and selling, bureaucracy, boredom, despair and all the forms of external authority that organize this misery for you, you’re obviously just an idle dreamer, well on the way to being locked up in a bin. Calm down, take some valium, switch on Channel 4, go down the club, find someone to screw with, score some speed, try roller-skating or take up gardening, invent a dance or turn your frustration into a song or a poem or something – just don’t take life so seriously – after all, we’ve all gotta compromise – what makes you so different? Why do you have to remind me of the anger I’ve managed to repress?

As the ruling scum’s servile guard-dogs, the cops, and the courts, get heavier so the rulers’ lies aim closer & closer to Goebells’ dream that “The bigger lhe lie, the more it is believed.” In the miners’ strike this is already a daily banality: everyday the BBC or ITV churn out lies with the cool calm assurance of bourgeois ‘objective’ truth (for example, on the day the strike became 6-months old, all channels published the lie that striking miners had lost £4000 in lost wages, as if the average miners wage was £160 a week, instead of the average £80 for 40 hours without overtime which was the true figure). It’s no coincidence that the monologue of the radio was one of the fundamental means of manipulation used in Nazi Germany. Since the war, the box has supplanted the radio as the main form of manipulation. Everyday the Left and the Centre churn out different lies and half-truths and the spectator is meant to join in on one side or the other, rather than make sides, rather than intervene to uncover the false choices of all hierarchies, of all wings of capital.

28/9/84:

Half a mile from Silverwood colliery, where just 2 scabs had returned to work, a convoy of cop vans are stopped by a 3 foot high barricade and are surrounded by pickets. The press and the cops refer to this as a “diabolical ambush”. “Striking Times”, a one-off radical paper set the following competition:

Striking Times Diabolical Competition

All you have to do is decide what truly happened in the so-called ‘Diabolical Ambush’ at Silverwood Colliery on 28th September. Was it:

(a). 9 police dog vans and a cop Range Rover were attacked by 700 miners acting on the

direct instructions of the NUM leadership? (Home Office version)

(b). 2 dog vans were overturned and one dog handler was knocked over, his dog escaping to attack both pickets and cops (Guardian, 29th September).

(c).500 pickets plus their cars were attacked by 1,500 police in riot gear? (Sheffield Police Watch version).

(d).Up to 3000 pickets threw stones at police vehicles and at pickets’ own cars by mistake? (Police version)

(e).Miners had finally had enough of bieng continually on the receiving end of police violence and harassment. The miners acted on their own initiative, not the NUM leaderships, according to the old saying “Attack is the best form of defence” (Striking Times version)

(f). Other journalistic lies and distortions?

Send your answers to Striking Times along with a cheque for £5. Please include a statement using not more than eight four-letter words on the role of the British Bobby in industrial disputes.

The lucky winner of this competition will win a cheque for £2.50p.

The police weren’t the only repressive arm of the State that the miners direcly confronted. In Burnley, a 19 year old pregnant miner’s wife was told by a Social Worker to “eat potato peelings”.

Round about this time, though it may have been earlier (no date) 2 striking miners (from South Wales, I think) in a car are driven at at full speed by cops and are foced off the road, their car crashing and they’re killed. Nothing in the press about it. And the NUM could’ve made more about it….

2/10/84:

Village of Rossington completely occupied by anti-riot squads equipped with vicious dogs; against this provocation, people succeed in building a barricade.

Round about this time (no date), the people of Wooley, near Barnsley built barricades across roads and at the pit gate. The fight lasted two hours without any arrests. A group of cops under hot pursuit retreated into the colliery and were immediately locked in.

4/10/84:

Just after midnight, about 600 pickets blocked the entrance to Hartlepool nuclear power station. 2 patrol cars get stoned by the pickets and were forced to withdraw. The miners then barricaded the entrance, ripping up fencing and setting it on fire. Two British Oxygen tankers which were driven up to the site were pelted with stones and one of the windscreens was shattered although the driver wasn’t hurt. John L:yons, general secretary of the Electrical Power Engineers’ Association condemned the pickets saying that the TUC had specifically excluded nuclear power stations from any action and the behaviour of the pickets breached TUC guidelines.

At Wooley colliery, hundreds of cops get pelted with stones for a short while.

5/10/84:

Once again, a scab, father of two, died – crushed by falling coal 3000 feet underground at Wolstanton Colliery whilst he was clearing a blockage. These kinds of facts could’ve been shouted at scabs on picket lines – and maybe sometimes they were.

In some of the most combatative mining areas, where the miners had been unable to pay their bills for 7 months, fuel workers refused to go in and cut off supplies, some out of solidarity, some out of fear of the reception they’d get. In Glasgow, a group of unemployed workers cut off the mains to the Electricity Board Office to give them a taste of their own medicine, and organised an “Instant Response Unit” to intercept employees going to cut off working class households.

This kind of exemplary act of solidarity was too rare throughout the strike; too often the support remained just that, rather than turning into any independent iniative to be acted upon. Supporters generally stood behind the miners struggle, rather than alongside them. The heroic, vanguard reputation of the miners worked against them – aided by years of Lefty mythologising, people saw their support as giving secondary backup activity to the strikers, rather than taking a lead from their own situation to initiate something. Just as the majority of miners ulimately abdicated initiative to the NUM leadership, so did ‘supporters’ abdicate initiative to the miners they supported.

Some time during the week 8th to 13th October (can’t be bothered to find the date), the IRA bombed The Grand Hotel in Brighton where Thatcher was having a piss at the time of the explosion. The London radio station vetted all incoming phone calls to the programme to make sure that only “outraged members of the public” would have their say about the Brighton Bomb. One woman slipped through the net and said that most of her friends saw “the funny side”. In fact, the bomb was a great show – the IRA’s image shot up in the eyes of the miners, and no-one could understand it if you said they just aspired to be another government. This uncritical admiration for the IRA was helped by the anti-terrost style of Thatcher’s rousing speech to the faithful, implicitly comparing violent pickets with the IRA knee-capping nationalists. After that, a certain anti-terrorist revulsion-inciting amalgam technique on the part of the Tories and the TUC developed against the picket-line violence, as if a hierarchical elite force aiming to take over the State, often killing indiscriminately, brutally punishing soft-drug dealers because they intruded on their own dealing, knee-capping looters, partly financed by sections of the American bourgeoisie – that this racket could compare with the direct autonomous actions of people fighting for some sense of community against State power. However, a helluvalot of miners had illusions in the IRA just on the basis of ‘our enemy’s (apparent) enemy is our friend’-type identification.

At this time, I suspected that the State would carry out some atrocity and blame the IRA or the miners or both, preferably. But the State was subtler than that, as we only discovered several years later.

15/10/84 – 18/10/84:

Grimethorpe, early morning of the 15th, lorries coming to load coal were bombarded with missiles; a worker left his excavator and it was set on fire. At midday, 200 young people, some wearing balaclavas, attacked the police station. A male and a female cop, who came to help put things in order, were chased off. The female cop, who had been known for her viciousness for some time, was caught, knocked to the ground, kicked and ended up in hospital. She said, “I am going back to work as soon as the swelling on my head goes down enough for me to wear my hat.” In the evening, people gather to attack the shops, while at the same time, several masked pickets ransacked the colliery control room and tried to set fire to the manager’s office. On the 16th, about 200 youths stoned the police, the police withdrew and 50 – 60 men and women built a barricade across the road with a car which was then set on fire; 3 shops had their windows broken and £100 worth of spirits was taken. On 17th October a 13-year old boy was arrested by 4 cops in riot gear.

All this was a response to the arrest on the week-end before of 19 people for ‘stealing’ coal off a coal-tip (expropriating the expropriators, more like). Whereas before the strike there had always been an agreement with management that miners could take some coal from the slag heaps, from the summer of ’84 onwards the NCB began prosecuting every miner caught helping himself. When a young teenager died on a slagheap collecting coal because part of the heap collapsed, papers like the Daily Mail blamed “Scargill’s strike”. Such professional manipulators will, hopefully, one day end up like the Mussolini or Hitler they once admired – hanging from a lampost or driven to suicide. The total value of the coal was £100.50p. – and miners were fined £375. A Grimethorpe miner, at a meeting on the 18th Oct., pointed out of the window at a cemetery and said that the coal morally belonged to the miners, “There’s men laid in them cemeteries that died through being gassed or explosions, having their legs blown off. They paid for that coal.”

At the meeting, the chairman of the South Yorkshire police authority, Mr.Moores, said the police joined the force as decent chaps and were then sent to training centres and came back “like Nazi stormtroopers”, adding that he “would defend to the last any policeman who used his truncheon in defence but I abhor situations where policemen are dishing out punishment as judge and jury”. A young miner got up at the meeting and said that no one condemned David when he stoned Goliath. Mr.Moores said that no one would get anywhere by throwing stones, to which miners responded “David did”. The Deputy Chief cop responded by quoting the Bible, saying “blessed are the peacemakers.”, and then added, “I have shuddered at many of the things said against police officers. For some of the things they have done wrong, I unreservedly apologise”. One member of the police committee, Councillor Tom Williams said the community would only damage itself through violence – “Just keep emotions down and give us a chance.” Here we have all the typical contradictions of British workers when dealing with the cops and their hypocrisy. That is, the police are seen only in specific circumstances as an arm of government policy – but the local copper is seen as somehow ok, and at least someone you can have a polite dialogue with, to whom workers feel they have to justify illegality in pursuit of basic needs. It’s probably not since the First World War that there’s been a working class culture that recognised cops as a whole as inherently part of the enemy. The intensification of ideological manipulation has something to do with it, but also it’s because the State recuperates real needs arising out of the misery of the market: psychos and muggers, arising out of the suppression of community, have to be dealt with, so the State presents itself as the protector. So even in situations of mass class struggle the complaint is that the cops aren’t doing their job – protecting workers from burglars, for instance. If a radical movement doesn’t take on the task of both protecting people from the State and from the ‘enemy within’ – i.e. those who embrace this dog eat dog world and prey on the weakest of the working class – then obviously the State will fill the vacuum.

17/10/84:

Clashes between cops and 2000 pickets at Wooley colliery near Barnsley. A cop has his face punctured in 2 places by pickets with darts in their fists. 25 cops injured officially. At Tow Law, a private coal stocking site in Durham, 700 pickets attack the cops with bricks from a ripped down wall, and 3 cop vans are overturned whilst the cops abandoned the vehicles and retreated into the depot. At Rossington, 2000 pickets tried to prevent 5 scabs going in. “This police horse box accelerated and swerved towards a group of pickets. Darrel got hit. I thought he was dead. Another two feet and he would have gone right under the wheels. Some lads went over to tell the police he was seriously injured and all they did was laugh. They started chanting ‘We hope he’s dead’. They wouldn’t call an ambulance”. `A wall was pulled down and used to stone the cops. 2 barricades were built, one set on fire. 2 cops were hospitalised

In October NACODS, the union of safety workers and colliery overseers, a union a majority of whom were what in other industries would be called “foremen”, was involved in a widely publicised dispute with the Coal Board over the conditions which its members were expected to have to face in order to get to work, and over closures. MacGregor had ordered them to cross picket lines at strike-bound collieries, provoking them into a major threat to go on strike, thus shutting down every pit, because it was illegal for a colliery to be in operation without safety workers. 9 years after the strike, Thatcher described on TV the crisis this provoked: “We had got so far and we were in danger of losing everything because of a silly mistake. We had to make it quite clear that if that was not cured immediately, then the actual management of the Coal Board could indeed have brought down the governement. The future of the government at that moment was in their hands and they had to remedy their terrible mistake”. It turned out, however, that all those who thought that a traditionally ‘moderate’ union would do such a big favour for the miners already on strike were wrong. Despite an 83% vote for a strike, the NACODS bureaucrats agreed to a deal over “revised conciliation procedures” just 24 hours before the safety workers and overseers were supposed to come out on strike. Under Thatcher’s instructions, MacGregor offered NACODS a sop – a mildly souped up closure review procedure, which, in the decade that followed, didn’t save a single pit, surprise surprise. There were no condemnations of NACODS by Kinnock or by Thatcher for refusing to abide by the decisions of the majority (as always, ballots mean fuck-all – what matters is how people act).

There were a few reasons why this strike didn’t happen:

–First of all, none of the moderate members of the moderate union had a tradition of going against their leaders, unlike in the NUM: despite the fact that the leaders acted undemocratically even in terms of bourgeois democracy, the overseers and safety workers had neither the will, the experience nor the audacity to go on a wildcat. Those most used to giving orders were also those most used to following them – so they submitted to the NACODS leaders.

–There were also external pressures not to show support for the miners at this moment. The media “revealed” that an NUM bureaucrat had met Gadafy, public enemy no. 1 after the killing of a policewoman supposedly by Libyan diplomats during a demonstration outside the Libyan Embassy, London, in April 1984 [12]. The meeting between Gadafy and the Union bureaucrat – the NUM’s top accountant, Roger Windsor – was very publicly broadcast on Libyan TV (so-much for the Sunday Times’ stunning revelations!) under Windsor’s insistence – he claimed that the NUM had nothing to hide in accepting this money. This put a lot of pressure on NACODS leaders and members not to side with the miners, who were rapidly being portrayed as terrorists – or , at least, in the pockets of terrorists [13]. As revealed about 10 years later, by a Lefty journalist – Seumas Milne – Windsor was working for Stella Rimington, later head of MI5, who won her spurs heading the MI5 section directly responsible for policing the dispute. Phones were tapped, the State surveillance apparatus of GCHQ deployed, buildings bugged, bundles of supposed Libyan cash faked. Windsor was at the time the highest ranking non-elected official in the NUM and was later revealed as a double-dealing security service agent positioned, almost a year before the strike, to destabilise the dispute. Later in 1990, he acted as chief witness in the prosecution of Arthur Scargill, when he claimed that money collected for the miners during the strike went to pay off Scargill’s supposed mortgage, when he never even had one (in fact, there’s plenty of evidence that much of this money went into Windsor’s pocket).

–The attitude of the miners themselves didn’t help: they were almost completely indifferent to whether NACODS went on strike because after all these were ‘foremen’ who’d humiliated them in the past and they rightly had complete contempt for their function (though not all of them were foremen). This was understandable given the fact that up till then they had been the bosses’ toadies – but hardly strategic. A total strike at this point would have meant almost certainly that the miners would win, and any return to work would have weakened the authority role of these overseers (as it was, their authority role was strengthened). To assume that people are immutable on the basis of their past and their most conservative past, is to ignore the process of struggle and of what happens when people are challenged to change. An aggressive direct challenge to them, which needn’t have involved challenging overseers personally known to the pickets, might have made them at least realise that their self-interest, their desire not to lose their jobs at least, lay with the miners. Pressure from strikers may have tipped them over into having a wildcat. Indeed, many NACODS members refused to go into work when confronted with a picket line they could very easily have crossed (invited to do so with the usual protection of the cops) as late as February 1985, when there were increasing amounts of strikers turning into scabs. Hardly the sign of people reluctant to strike. But the miners treated the whole situation impassively, as if it was something they couldn’t affect, certainly something they were indifferent to affecting. One suspects that this attitude on the part of the miners was also part of a hangover of the 70s strikes – when the miners won on their own. They believed they could do so again. Partly stemming from this, many miners had a vanguardist notion of themselves, that they were the most radical section of the working class, even though, for instance, very very few identified with the 1981 riots at the time that they happened (by 1984 this had changed – retrospectively they understood these riots).

At this time, as later admitted by Government ministers and even Thatcher herself, the miners were close to winning. 10 years afterwards, Frank Ledger, the Central Electricity Generating Board’s (CEGB’s) operations director, recalled the situation as having been verging on the “catastrophic”. Throughout the autumn months, there was a serious risk of power cuts. Secret internal forecasts predicted that – in the words of Lord Marshall, then CEGB chairman – “Scargill would win in the autumn or certainly before Christmas”. In a tense meeting, a “wobbly” Thatcher told him she would have to send troops in to move the coal (see this recent article revealing her belief in using the army). If that had happened, Marshall believed the power workers “would have gone out within a week”. Thatcher was persuaded to hold off, while CEGB managers started to bribe certain groups of workers with vast wage hikes to move the vital coal supplies (mainly, lorry drivers, who’d been particularly petit-bourgeoisified – encouraged to become self-employed – after their collective victory in the Winter Of Discontent, when most lorry drivers had worked for bosses). The miners’ failure was to fail to communicate directly with electricity workers – not to try to overcome the separation imposed on them by the cops at picket lines keeping them from talking to power workers and lorry drivers – but of course, such a possible course of action would have been very difficult, though not impossible – it would have involved making connections away from the immediate power station gates, which the cops controlled. UK workers have often had a crippling tendency to rely on solidarity between workers in different industries to be negotiated through official union channels; if the solidarity is not forthcoming this is usually accepted as an immovable fact of nature. Yet situations where workers could talk face to face, unmediated by their official representatives – such as a simple visit by strikers to the workers’ local pub – were rarely attempted as ways of forging links. The official political/union arena, with its tedious bureaucratic rituals of motions, meetings, negotiations etc were allowed to have their intended effect of dissipating energy, spontaneity and initiative.

November 1984

A divided ruling class…NCB bribe…more rage against the State…

…Willis attacked…NCB figures for scabbing…death of scab driver …

…Kinnock…discussion on class violence…

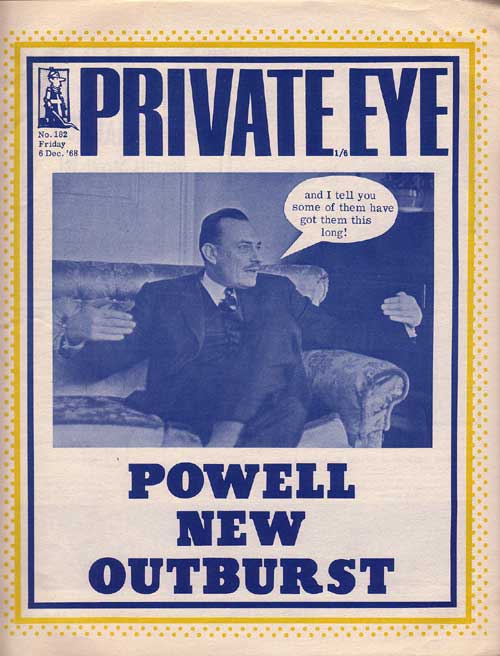

“Britain is fast becoming that most dangerous of societies, a nation in which Government and the governed speak different languages…The atmosphere is reminiscent of the countries on the eve of revolution in the past, where the ruling class never mingled with the people at large, did not know how they lived and seemed not to care what was to become of them…Beneath the glossy conventional surface of tolerated opinion and authorised vocabulary, the absence of real communication permits and encourages the growth of resentment…Resentment at the apparently wilful blindness and ignorance of those in authority, resentment at the apparently unrecognised destination towards which those living under authority are being inexorably borne…hope has become extinct, and where there is not hope, people will not hear.” – Enoch Powell, 10th November, 1984.

1968 Private Eye cover

As a somewhat ‘independent’ member of the ruling class, detached at least from any party allegiance, after having been kicked out of the Tory Party for his racist demagogy and after urging voters to support the Labour Party in 1974, Powell could occasionally express openly what other rulers dared only mutter in private. Of course, he had to pose things in terms of ‘resentment’, rather than class anger because for the ruling world there cannot be any reversal of perspective, any fundamental hatred of hierarchy – it’s all just a matter of envy and spite. Nevertheless, substitute the word “hatred” for resentment and Powell’s quote is a lucid insight into the atmosphere of Britain in 1984. And now? – there is far less real hope now than in 1984 because at that time practical hope was being developed in the subversionof the “destination towards which those living under authority [were] being inexorably borne”– but now people with plenty of false hope are “listening” much more to the dominant authority of the commodity economy, even if they bemoan all its results, precisely because the hope of some genuine reversal of perspective, the hope of a revolution, seems to be becoming increasingly extinct.

It’s a measure of how out of touch many ‘revolutionaries’ are that they have no idea or, even no interest in, how close to a revolutionary explosion Britain was at this time. If the miners had won, it would certainly have encouraged a far more widespread movement as well as a lot of repression, but also inspiring a lot of resistance globally, especially as the possible coming to power of a Left-nationalist-social democratic government under the likes of Tony Benn would very likely have caused a run on the pound and a realisation that reform or keeping things as they were was not an option and…..But this is only if only. And then again, fear, including the fear of revolutionary upheaval by a significant number of proletarians, was certainly a factor in why this chance was missed.

Powell’s fears, and that of sections of the ruling class in general, are illustrated by the previous chronology of violence but this rage against the State continued into November and beyond, in part incited by the NCB offering a bribe of £600 – a hell of a lot in those days, and especially for those who’d not had an income for 8 months – to miners who returned to work before Christmas (in addition they were informed that their income would not be subject to tax):

7/11/84:

Barricades built across road to Whittle colliery, Northumberland, to stop 27 scabs, 12 having been persuaded to return home. A bus carrying the scabs was stoned, and the barricade set alight.

9/11/84:

Just 1 scab escorted to work by 1000 cops. Barricades burnt, 2 cop Range Rovers crashed as cops were hit by a fusillade of ball bearings fired from catapults, along with loads of milk bottles. An air gun was also used against them.13 cops injured (as well as the usual injuries to miners) and a police horse visor was smashed. Miners rolled a disused workman’s hut twoards police lines, then moved a second hut nearby and set it alight.

12/11/84:

About 25 pits experience significant violence against scabs, cops and NCB property. We mention half. At Dinnington, barricades were set alight, stones hurled relentlessly at the cops and a steel rod speared through colliery windows. A concrete block and two petrol bombs, one failing to explode, were hurled at the cop shop. A 4 inch bolt was hurled through the cops window. 27 street lamps smashed to the ground. £1000 worth of electrical equipment stolen from looted shop. Maltby: 3 cop shop windows broken, street lamps pulled down as barricades and a garage and general store near the pit are looted. Hickleton: a steel wire was strung across the road aiming to severely injure cops on horseback, but it only tore off the aerial of an NCB management car. 2 NCB security guards attacked by a group of men wearing balaclava helmets, one ending up in hospital. 2 management cars were overturned, one set on fire. 33 cops were injured. Brampton: barricade set on fire near the co-op, whilst cops standing behind shields were repeatedly stoned. A huge turf roller was taken from the nearby cricket ground and rolled through police lines. A molotov lands near a cop car. Cortonwood: stones, bottles, nuts and bolts used to pelt cops. Molotov hits cop Range Rover. South Kirby: colliery offices broken into and ignition keys removed so that earth-moving machines could be moved to block roads. Windows smashed in the NCB buildings and fires lit. Dodsworth: fires lit and 3 foot steel rod pitched through pit windows. Darfield Main: pit roads blocked and stores looted. Dearne Valley: NCB office windows smashed and a foklift truck and crane damaged. Rossington: pit control windows smashed and 3 cars and a motorbike overturned. Barrow: trees felled and hauled across the road as blockades. Oil poured all over the road. Stainforth: A Sunday Times cameraman was punched and had his camera snatched, with the film dropped in the mud. “Fortunately it’s only my pride that was damaged”, he said – as if anyone working as a cameraman for Murdoch has some pride left to be damaged. St.Johns, S.Wales: pit gates blocked by telegraph pole, so manager abandons car, which is then overturned. Cwm, S.Wales: bottles, stones and iron bars hurled at cops, as old railway sleepers were used as barricades. etc.etc.etc.

13/11/84:

Norman Willis, head of the TUC and ‘benign’ bastard with the ‘common’ touch, denounced the violence at a meeting in Port Talbot, but his speech was barely audible as strikers chanted “Off off off!”. He apologised for the lack of support from other unions, but stressed that the TUC was “backing the miners in the very best traditions of the trade union movement”. This was undoubtedly true – traditions which went back to 1926, when the TUC also did its best to fuck over the miners, though we suspect that these were not the traditions Willlis was talking about. In a famous incident, 3 Welsh miners clambered onto roof supports and lowered a rope with a noose on the end to loud cheers from the audience. Justified as the miners’ criticism was, it still remained at the level of ‘the leadership have failed us again’ – with all the acceptance of the leader/follower relationship that this implies. Only a seizure of initiative by miners on the ground to themselves approach workers in other industries directly could have transcended this. 8 years later, in 1992, I saw Willis with his entourage of bureaucrats in the crowd of a miners demo against the decimation of the pits proposed by Major’s government, and shouted “This time we’ll string you up properly”. Having had 8 years to work out some kind of clever pun, he retorted, “Thank you for your support”, the kind of typical joke people tell at their own expense designed to take the wind out of the sails of an attacker. He’s now a Lord, for services rendered to Thatcher and to capital in general.

Norman Willis: no noose is bad noose

Goldthorpe: a bus driver driving scabs to work had his bus attacked and broken into and he was beaten up. Frickley: 42 cops injured. Barrow: power line brought down. Celynen pit: cops bring out the riot shields for the first time against missiles, as 18 miners refused to accept the decision of a mass meeting of the 12th to continue supporting the strike, and turned into scabs. Strikers occupied NCB premises, and were evicted by the cops, whilst tyres of a TV crews van were let down.

The NCB claimed that 56,000 miners were working, the vast majority having scabbed from the beginning, whillst 133,000 were on strike, a figure of 189,000, 7,000 more than the total number of miners accounted for in the boards accounts, a contradiction never pointed out by the media, which was generally becoming recognised by strikers as “an arm of the State”.

The fears amongst the ruling class of everything going pear-shaped were expressed not just by Powell, as in the quote above, but also by the former Tory Prime Minister, Harold Macmillan, who, after praising Thatcher for her “courage, determination and persistence which must surely be admired by all reasonable men and women” then went on to bemoan the dangers of the strike, “It breaks my heart to see what is happening in the country today. This terrible strike – and by the best men in the world. They beat the Kaiser’s army. They beat Hitler’s army. They never gave in…We cannot afford this kind of thing.” (interestingly, he also attacked the growing submission of British capital to American capital, something that many of the anti-Iraq war movement today also bemoan, wthout seeing how conservative such a limited take on world politics this is).

15/11/84:

Savile pit: strikers stone the pithead baths where 17 men have supposedly returned to work. Windows are smashed. Goldthorpe: barricade built and set alight because of one scab returning. BBC cameraman has a stitch inserted in his chin after being pushed while filming.

Father Christmas arrested outside Hamleys in Regents Street – a member of Westminster Miners Support Group launching a Christmas toy appeal for miners’ kids.

A striking miner, 47, father of 4, dies whilst digging for coal on a tip, trapped under tons of rock falling on him. Virtually no mention in media.

19/11/84:

NCB geological exploration unit in S.Yorks abandoned by staff after being sytematically wrecked. Computer terminals and keyboards smashed, 22 out of 24 offices vandalised and rooms flooded after a mains pipe was burst open. Windows smashed and typewriters and other equipment damaged. An IBM computer linked to the NCB’s computer centre in Cannock was smashed. The 20 members of staff had to be placed elsewhere in Yorkshire until the building became operational again. The NCB said that the incident brought their whole planning procedure to a halt as they did not have access to records. How sad. Damage was estimated at £250,000. One of the better critiques of computers, which now dominate our daily lives in ways unthinkable 20 years ago.

Aberaman, South Wales: pickets smashed window of Land Rover taking a single scab to work, and a cop van windscreen was broken. At Merthyr, S.Wales barricades were built and oil poured on the road outside the pit. According to (dubious) NCB statistics, 85 men are scabbing in South Wales out of a total of nearly 20,000 miners – a bit over 0.4%.

24/11/84:

Yorkshire scab’s £40,000 house gutted by fire in arson attack. This was before the protperty boom – £40,000 for a house in this part of the country was a hell of a lot of money. The owner claimed that strikers had threatened to kill his 2-year old daughter and that the blaze had started in her bedroom. Not sure if this was the case, but a couple of arson attacks which at the time were attributed to strikers turned out to be self-inflicted, done for the insurance money. Certainly, to threaten and even try to kill the daughter of a scab was not the kind of thing 99.99% of strikers even remotely considered. Another scab was hospitalised with a broken shoulder, broken ankle, bruised ribs and other injuries when beaten up by masked men. In a well-publicised visit to the hospital of the latter, the former fire victim (?) urged the NUM to change its rules so that Scargill could be got rid of. The NUM, the NCB and the cops were all united on the attack on the scab: they condemned it. The media, of course, always gave full publicity to the attacks on scabs – attacks, including arson attacks, on strikers were never mentioned.

All emergency calls throughout most of Mid-Glamorgan were blacked out by the sabotage of a South Wales police telecommunications station – 20 inch-thick cables were severed with an axe.

Merthyr Vale, S,Wales: 11 cops injured, one suffering a fractured cheekbone and a bruised eye.protecting 2 scabs.

By the end of the month, the NCB bribe had not worked. Even according to the grossly inflated figures of the NCB (which even a Tory recently admitted, because it was safe to do so, were absurdly inflated), the increase was only 8000, leaving 50,000 working – most of whom had never been on strike in the first place , and 140,000 on strike. Admittedly these figures didn’t make sense – but even within their own terms, this meant, that in the areas most threatened by closures – Yorkshire, Kent, South Wales, Scotland and the North-East there were at this time 113,000 strikers out of a total workforce of 116,500. Pretty solid after almost 9 months on strike!

30/11/84:

First and only death on the enemy’s side during the strike, near Merthyr pit. A concrete block dropped on a mini-cab taking a scab to work killed the driver. This is an occasion for endless horror shock pronouncements by the media and the State, with the Sun, the paper that cheered the sinking of the Belgrano with “Gotcha!”, leading the attack on “anarchy and murder”, complete with photos of the scab-drivers’ family, a classic hypocritical manipulation of the emotions. The families of the Belgrano sailors were never shown, any more than the families of Joe Green or of anybody else killed by scabs or cops were shown. Why mention the obvious? Because in these chronicly ignorant times, the obvious is often the last thing most people think.

3/12/84:

Kinnock denounced the killing of the mini-scab driver, as well as all picket line violence, during a speech on a platform shared with Scargill. “You shame us all”, he said of the men who did it. Had Kinnock said anything about David Jones’ murder? About Joe Green’s? About the other deaths of miners or their kids scrabbling for coal during the strike? About the cops who drove at full speed at strikers in a car, forcing them off the road and killing them? About the oh so tragic deaths of scabs in pits due to unsafe work conditions during the strike? No – but he had had nothing but praise for Indira Gandhi, who, before being assassinated, had ordered the shooting down of up to 100 blind demonstrators. Kinnock, some time later, went on to support the Gulf War, which killed 200,000 Iraqui civilians. Those who attack anti-hierarchical violence from their position in the hierarchy attack it because they know that they could be the victim of it – they want this society to have the monopoly of violence.

Scargill himself denounced all violence “away from the picket lines”, dissociating himself from what had happened in Merthyr. Sadly, no-one heckled him for this or for sharing a platform with Kinnock. Kinnock’s speech, which was inaudible for the first 5 minutes, was permanently interrupted by shouts of “scab”, “traitor” and “Judas”. These insults weren’t entirely accurate: Kinnock only visited one picket line during the whole of the strike, which he did for the cameras, and didn’t cross it, so ‘scab’ made no sense. If he’d done that, he’d have had absolutely no credibility within the Labour Party (or even for the rest of the pro-strike supporters) who needed him to play up to his down-to-earth image so as to represent the working class in a period when the class struggle could’ve gone either way, all the better to fuck us over. “Traitor” is hardly appropriate either – those whose career is part of the State (either as an M.P., or in his capacity as President of the European Union, and now as a member of the House of Lords) cannot betray the class struggle since it implies they are on the side of the struggle; in fact they would only betray themselves, or, at least, their well-paid complicity with this society which their role implies, if they sided with the class struggle. As for “Judas” – you usually apply this to friends who betray you, and Kinnock was never a friend: he himself declared he was “the policeman’s friend” and said, at one time, that he’d wanted to be a cop. Some time after she was forced to retire, Thatcher praised Kinnock for his gentlemanly conduct. That’s as much as can be expected from “Her Majesty’s Loyal Opposition”. Those who have always looked to the Labour Party, strangely use the same kinds of words (such as ‘traitor’) to attack Blair, when, as part of Her Majesty’s Loyal Opposition, he’d always shown his true colours – e.g. by refusing to support the signalman’s strike of ’96, despite 95% of the population supporting it. So much so that Thatcher herself recommended, in 1997, that Murdoch plump for him, since a further continuation of Tory rule might backfire against the ruling class. As a piece of graffiti painted on a wall outside a public meeting where Kinnock was speaking just a few days after the end of the strike said, “Kinnock, like the rest of the Filth, like all leaders, is only doing his job – policing autonomous class struggle.”[14]

In the days that followed the killing, many strikers showed none of the remorse that was demanded of them by the NUM, the media, the Labour Party and the rest of the power of this society – “Go get a mini-cab” was constantly shouted at scabs going into work. And just 4 days after the death, a 3 foot metal spike was dropped from a Derbyshire railway bridge onto an NCB van carrying 100lb of explosives, the blunt end penetrating the metal and lining of the cab roof. Cops said that those who did it, if found, could face a charge of attempted murder. And this violence was “away from picket lines” – so not something approved of by Scargill. And a cab from the same firm that had hired the killed scab driver had its window broken, the driver being hit in the back by an 8lb stone, on 16th January 1985.

It’s maybe hard to comprehend in today’s atmosphere of depressed indifference why strikers could be so violent towards scabs. When class conflict is intense, when it really matters, the conflict between those who are actively resigned to the violent stupidities of this world and those taking the risk of opposing it is fundamental – there can be no reason for “tolerance”: such “tolerance” is tolerance for a complicity with a very brutal enemy, an enemy which kills with the swipe of a pen or a bid on the stock exchange and which is prepared to destroy this world to insure the victory of the economy. As I said in “Miner Conflicts…”:

The working miner has all the reasonable lies of the commodity economy on his side: he knows that £1,000 for every year worked isn’t bad compensation for having slaved his guts out to be able to consume the videos and three-piece suites of his choice. The cynical dreariness and hierarchical ‘security’ … seems almost ‘natural’ to those who see their own narrow immediate interest as separate from their class interest. It is not merely the cops and ruling ideology which break up the possibilities of class solidarity: the Notts miners are not victims – they have consciously chosen to accept all the hypocrisies of the State. They know all the media crap about the cops protecting their “Right To Work” (read: Right To Be Exploited) is bullshit, even in it’s own terms: it’s a “right” their continuing to work is going to take away from thousands of others. They know that all the media crap about “Democracy” (read: the right of each isolated intimidated individual to choose who is going to isolate and intimidate him) is bullshit: when – in 1977 – all the miners voted overwhelmingly against productivity deals, Nottingham area voted separately, and undemocratically, for their own bonus scheme. They know that they too will be the victims of pit closures…..Those who choose, with the support of the whole weight of the commodity-spectacle, to reduce their lives to a narrow survivalist notion of their immediate interest obviously regard history , both past and possible future, with equal indifference.

Undoubtedly in periods such as this, almost all of us, from very different levels in the hierarchy (and it’s these levels that are vital), support, in practice, this brutal world – for example, the poor in the UK buy cheap goods often made from death-inducing conditions in countries such as China. We cannot avoid participating in violence. Which is why, when people risk attacking the system violently all those who denounce them become very definite friends of the violent system that crushes people daily, even if they claim to be pacifists. The economy kills – whether it be the thousands of old people who die from hyperthermia each winter because they can’t afford to pay gas bills or nurses avoiding treating dangerously ill patients in casualty so that they don’t get the sack for prolonging, beyond the target times, the waiting time of less threatened patients or…the list is endless and anyone reading this far will know how violently crazy the commodity economy is.

Work accidents and other disasters caused by the need for profit are only the more visible aspects of this violence. The enormous levels of stress and psycho-socio-somatic illnesses, even in kids and teenagers oppressed by the increasing pressures of an education system geared to intensified exploitation at work, are probably a more significant part of this violence.

We cannot renounce our share of violence – directed at the right people at the right time. However, if people seem wary of riotous violence it’s partly because riots ain’t what they used to be. A riot against the cops in Bradford in 2001 also involved crazy psychotic behaviour such as the parking of a car right across the entrance of the Labour club and setting fire to it, preventing those inside from fleeing. Though they managed to get out through windows, if this tactic had succeeded it would have been a massacre. The increasingly mad behaviour of some young people is a sign of how defeated all sense of community has been since the strike. Fewer and fewer people have any idea who their real enemies are.

If there was a big riot now in an urban working class area it might be really depressing, scary and horrific – the number of gangsters and anti-social vicious youth around nowadays would possibly see it as indiscriminate open season and easy pickings on the general public. So if such riots were to maintain some clear anti-hierarchical perspective, it’d be necessary to create some way of dealing with these psychotic elements – by organising some kind of healthy (as opposed to crazy) vigilantism. However, it’d be a mistake to think of riots as automatically outmoded in the present epoch: a break with the normal violence of capitalist daily life involves violence as the physical expression of this break, and though such violence might not conform to a theoretical ideal of what should happen, proletarians are going to have to deal with such contradictions when they arise, not condemn them but to find some practical way of overcoming their miserable side. Maybe this would involve occupying public or empty buildings so as to at least create an area in which people can work out such practical questions in some form of mutual dialogue. Just because something like a riot or a strike doesn’t nowadays develop into something new and different in a positive way doesn’t mean we should say such methods of struggle are automatically outmoded.

Most people think of violence as individuals or gangs attacking you for money or for perverse excitement and somehow think that an attack on a scab is like that, because violence is violence is violence, making no distinction. Whilst in times of intense class struggle verbal or theoretical violence might be more appropriate towards the more passive spectators, physical violence towards those who are actively supporting the brutality of hierarchical power, like scabs, is essential. However, given the enormous retreats and defeats suffered by the masses of individuals, it’s hard to know whether violence towards scabs today in fact advances the struggle. But one day such violence will be both appropriate and strategic.

During the strike, various professional feminists condemned the violence of the pickets towards the cops as typical macho posturing, making an equivalent between the cops and the picket’s violence. This was not echoed by the women directly involved in the struggle – the miners’ wives etc., who knew well the cops’ brutality and generally supported the violence. The logic of this crass feminism would be to condemn the actions of a woman who hit out at a rapist as mere macho posturing. In other words, to effectively say you can and should do nothing against hierarchical violence if you want to maintain some feminist purity/political correctness/moral superiority.

The nauseating 20th anniversary programme “WhenBritainWentToWar” showed the Battle of Orgreave with the song “When two tribes go to war money’s all you can score.” sendingthesubliminalmessagethat this was a tribal conflict, both equally violent and equally to blame and equally having a narrow tribal mentality. For those who see things utterly superficially, this kind of rubbish might work. But it’s kind of obvious that it was the cops who were scoring big bucks (two and a half times their normal already inflated wage[15]) whilst the miners were deprived of any income other than the pittance given them by the NUM for picketing and Social Security and anything they could get through collections.

The Last Three Months

Collections, charity and the Band Aid spectacle…strikers Christmas…

…Snow fun……Power cuts…the subtle sell-out…

…contradictions of low level NUM officials…increasing scabbing…

…Tony Benn…indifference towards the strike…Paul Foot…

…the bitter end…

As mentioned in the previous chapter, Father Christmas, a collector for the striking miners, was arrested mid-November. Collections up down the country were subject to police harrassment, collectors often having the money confiscated – but then the working class have always been robbed.

Recent picture of Slob Geldof and his mate: for the most interesting account of the Gleneagles conference see “Aufheben” #14 (October 2005).

Recent picture of Slob Geldof and his mate: for the most interesting account of the Gleneagles conference see “Aufheben” #14 (October 2005).

At the same time as thousands of people were giving money and gifts to the strikers, Band Aid was launched by Slob Geldof [16]. In Apocalypse Now, the main character says after an accidentally shot Vietnamese woman, bleeding profusely and half-dead, is given a plaster “First we shoot them half to death then we give them a band aid.”– the kind of one-off insight one occasionally hears amongst the pile of dross coming from the movie industry. That more or less says it all about Band Aid and all the subsequent guilt-quenching spectacles brought to you courtesy of the same society that starves millions. The condition of aid is that the recipients produce cash crops, which makes them utterly dependent on the world market, and destroys the margin of self-sufficiency they had. In this way Aid – dependent also on compliant governments – kills as much as Third World debt (incidentally in 1985, for example, – the year that Band Aid supplied the money it collected to Ethiopia – Africa’s debt was 3 times the amount given by all the nicey nicey charities to the starving). Moreover, in presenting illusions that one can somehow save lives through the charity business it props up the system ideologically and reinforces resignation and illusions, making people believe that something less than global revolution can assure that the unnecessarily starving can survive. Is there any coincidence that Band Aid was launched at this time – when the possibility of challenging the system of mass slaughter, the world market, was a genuine concrete threat? Though for Geldof himself, the concern for the world’s poor was merely a career move, for the rest of the dominant society it served a very useful function as a distraction from the essential. Some journalists even made direct comparisons between giving to the deserving poor – the starving Ethiopians – and giving to the undeserving poor – the striking miners (the obnoxious Julie Burchall, whose career was and is based on an ugly aestheticisation of petty, shallow, arbitrary ‘shock’ provocation without point, was one).

The collections for the miners, whilst also having some of the defects of charity insofar as they were often seen as substitutes for solidariity action and were extremely unevenly distributed, were also self-organised expressions of identification with a real movement of opoposition. Loads of people throughout the country used the collections as a point of contact, a place where they could talk about the news, about what was happening in the strike and about themselves.

Before this intensified spectaculisation of Giving epitomised by Band Aid, Comic Relief, etc.etc., the tendency was for people to give money – but not to make a song and dance about it. Few made much about giving to the miners, for instance – it was just something that had to be done [17]. But since then, the tendency has been to make a big moral thing about how much or often you give, people more and more feeling the need to wear their pure hearts on their designer sleeves. For most, charity is simply an instant cleansing of the soul, a redemption for the ‘sin’ of being better off than someone lower down the international hierarchy, who are seen as merely victims to be pitied, not fellow proletarians in struggle with whom one can express practical solidarity. “There’s always someone worse off than yourself”just keeps the international division of labour going: on the one hand it provides ‘solace’ for those who remain passive before their own misery, on the other hand, it substitutes mutual recognition and a sense of responsibility for changing the world with mere guilt.

***********************

“In anticipation of Christmas, at the end of September me and a couple of others decided to go round toy shops on a regular basis and accumulate loads of toys, using large coat pockets and bags, to be given to miners’ kids at the end of the year. This has been recounted in ‘Jenny’s Tale’ in a slightly embellished form: “He had asked smart London shops for donations to the miners’ strike and those that didn’t cough up he and his mates would rip-off blind. Mind you, even those shops that agreed also were shoplifted, but it didn’t really matter as they had more than enough in this society of raging inequality.” We certainly never asked them, as most of them were in wealthy areas and wouldn’t have given us any toys if we’d asked, and asking would have certainly made it very difficult for us to shoplift since they would have been suspicious. No – we just simply shoplited them, helped, on occasion, by others. It might have been that someone else elaborated on the story to Jenny, because, as it is, it’s fairly banal, though we helped save the Christmases of 2 pits – Kiveton and Monkwearmouth. The latter seemed largely indifferent, even when we put two nicked battery-operated fluffy rabbits that moved onto a table and set them up in a fucking position – a somewhat dour lot dominated by the Communist Party”.

Despite the image perpetuated by the media of misery for striking miners’ families at Christmas, and in particular by the well-known film Billy Elliottwhich presented the father and Billy as alone, cold, presentless and almost foodless, many if not most strikers had a good communal Christmas – and for many it was better than the usual nuclear family-round-the table watching telly, having a traditional Christmas row, with the kids complaining that they haven’t got what they wanted or wanting more…Though undoubtedly there were far less presents for the kids, the excited collective atmosphere and sense of support from others made it, for some at least ”The best Christmas I had”, ”Everyone banded together”, ”Lots of cheap wine flying about – brilliant – really good atmosphere”as various miners put it on the BBC’s 20th anniversary programme. Sure, there were always hardships, but community in struggle, even with poverty, is infinitely more enriching than the impoverishment of conspicuous consumption. And many miners stole to make up for their poverty, to make sure their kids had enough – theft as part of struggle is always simply one method amongst many of stealing back the life that’s been stolen from us. Another miner, who’d had a fight with the cops, been arrested and beaten up, said, ‘‘I got more women that Christmas than I’ve had since. Unbelievable.” At this time it wasn’t hierarchical power and money that (supposedly) was an aphrodisiac but the passion of revolt: one became attractive by asserting oneself against everything that repressed oneself. Although at that time there was a common practice of middle-class lefty women trying ‘a bit of rough’ during the strike by getting off with a miner, as they came into closer than normal contact with them through miners support groups etc., it’s hard to know whether this was the case with that guy, as it seemed the Christmas festivities at Hatfield mainly involved the locals. However we shouldn’t ignore the fact that there was added prestige at this time on the lefty scene to be seen to be shagging a striker (or a miner’s wife) – a kind of ‘donate your body to a miner’ attitude. Patronising but true.

Christmas also saw one of the few collective attacks on the NUM by striking miners. A few days before Christmas, hundreds of Durham miners (can’t remember what pit), promised £40 Christmas money by the relatively cosy officials, when given just £10 each, ransacked the whole of the Union building, looting everything that hadn’t been nailed down, including furniture.

* * * * * * * * * *

One of the lighter incidents of the strike happened about this time, though perhaps a bit later – in January: in the snow at Kiveton Park, a Chief Superintendant – Nesbit – drives up to the picket line and sees a snowman with a cop’s helmet on it. This is clearly an affront to the dignity of policemen everywhere, so he orders the other cops to get rid of it, but they can’t be persuaded – it’s too silly. So he gets in his cop car and drives full speed at it. Little does he know that the snowcop is built round a concrete post – with the obvious result of a smashed up cop car, a very undignified Mr.Nesbitt and a very happy picket line, a story that spreads, despite the snow, like wildfire and keeps strikers warm for weeks to come, and picket lines reverberate with the following song, sung to the tune of “John Brown’s Body”: “The pickets built a snowman Around a concrete post. The pickets built a snowman Around a concrete post. The pickets built a snowman Around a concrete post…But Mr.Nesbit mowed it down. Silly bugger Mr Nesbit. Silly bugger Mr Nesbit. Silly bugger Mr Nesbit…And he needs a new Range Rover Now!”.

* * * * * * * * * *

The year ended with one of the most significantly stupid statements from Peter Heathfield (NUM general secretary) and from Arthur Scargill that there would be no power cuts this winter, and that they’d never said there would be power cuts. ”I accept that if this Govenment, regardless of cost, is prepared to use substitute fuels in power stations, then with the current level of economic activity, and with a mild winter, it is probable that there will be no cuts. The Central Electricity Generating Board will survive on a wing and a prayer.” , said Heathfield, adding ”I never anticipated power cuts’‘. This was a double lie:

1. They’d both repeatedly said there would be power cuts, as did the NUM paper The Miner.

2. More importantly, there had been power cuts and there continued to be power cuts in January. Not many and not nearly enough, but significant ones neverhteless. And if the strike had continued there certainly would have been more, particularly with the blacking of international coal distribution to the UK on the cards.

At a time when, as never before or since, the pound almost reached parity with the dollar – and this solely because of capital’s fears about being defeated by the miners, one has to assume that these statements amounted to a sell-out. The point was not to be superficially upbeat about power cuts, but being so downbeat as this was deliberately demoralising. On January 15th, Edward Heath, former Tory PM, was more encouraging of the strike than Scargill and Heathfield had been two weeks previously. Referring to the collapse of sterling, he said, «People abroad are worried about a prolonged miners’ strike which is very damaging indeed.» Certainly the NUM leaders had a more demoralising effect. One wonders whether this was to give a nod to the NCB that they were worth negotiating with because they could help to deflate things or if this was just plain stupidity. But the national negotiations did start up again at this time (in 1981, the most exemplary action in Poland was the use of public loudspeakers to broadcast the negotiations going on between Solidarnosc and The State, a way of reducing the chance of a sellout, which has rarely been used as far as I know, and sadly was never used in the miners strike).