Deepl translation of this published 3rd September 2021

SF note: this is not a radical text by any means but I’ve put up this translation because it brings together some pertinent criticisms of how “fact checking” functions.

For some time now, most of the mainstream media have been fulfilling a purificatory function: distinguishing the false from the true. Self-proclaimed fact-checkers pinpoint incorrect information and its improper authors. An inquisition that, under the microscope, has many shortcomings… and many dangers.

In this article, we look at 7 problems raised by fact-checking when it is practised in a simplistic, biased or manipulative way.

Contents:

Frugal fact-checking: inconsistency in citing sources

Emotional fact-checking: announcing reason and brandishing emotion

One-sided fact-checking: the end of the dialectic

Defamatory fact-checking: the death knell of the medicine man

Self-contradictory fact-checking: the truth, when it suits us

No-questions-asked fact-checking: the case is closed!

Dramatic fact-checking: welcome to the Karpman triangle!

The fact-checking movement, or ‘verification journalism’, is not new. It began in the United States, where it has its roots, almost 100 years ago i, but in recent years it has tended to become widespread in the Belgian and French press. It took on a very invested dimension during the health crisis.

Some examples in France:

https://factuel.afp.com/ (L’AFP)

https://www.lemonde.fr/les-decodeurs/ (Le Monde)

https://www.francetvinfo.fr/vrai-ou-fake/ (L’audiovisuel français)

https://www.liberation.fr/auteur/service-desintox/ (Libération)

https://www.20minutes.fr/societe/desintox/ (20 minutes)

Some examples from Belgium:

https://www.rtbf.be/info/dossier/faky-fact-checking (La RTBF)

https://www.lesoir.be/336427/sections/le-vrai-ou-le-faux (Le Soir)

Some see this phenomenon as a response to the need to shed light on the large amount of false information or rumours circulating on social media. Others see it as an opportunity to restore the image of journalism at a time when the credibility rating of the traditional press is falling in public opinion ii.

However, a paradox is emerging. “Fact-checking is criticised by some citizens for claiming to tell the truth, a criticism that is becoming increasingly common against the media in general,” Cédric Mathiot, journalist in charge of the Désintox section at Libération iii, lucidly points out.

On the other hand, it seems that fact-checking is having an effect. A study conducted in 2019 by American researchers indicates that fact-checking significantly influences political opinions, even if readers are more or less permeable to it depending on their beliefs and knowledge iv.

Of course, fact-checking is sometimes beneficial

Before delving into the excesses of fact-checking, as it is sometimes used today, I want to pay tribute to the principles of verifying information and cross-checking sources, which are the pillars of quality journalism, the guarantor of a democracy where citizens can make informed choices.

For example, social networks are awash with quotes allegedly attributed to charismatic figures such as Steve Jobs or Gandhi, but which they never actually said. Albert Einstein would be rolling over in his grave twenty times over if he knew how his intelligence is regularly exploited to increase the impact of the messages we want to put across v.

“If bees disappeared from the face of the earth

man would only have four years to live”.

… this sentence often attributed to Albert Einstein

does not appear in any archive vi.

At other times, it is politicians who are attributed with statements they never made. All political camps are potentially concerned, including President Emmanuel Macron himself vii.

In some cases, the rumours may come from the media, which have been too quick to spread unfounded information, the verification of which is beneficial to everyone viii. The race for information and ratings sometimes leads to missteps.

So yes, of course, verifying the veracity of information is an important foundation without which any reasoning or decision would lose its consistency.

In this sense, fact-checking is particularly suitable for simple, concrete and 100% verifiable information.

For example:

Are some airlines banning vaccinated people? ix

Are 45,000 churches threatened with demolition? x

Is it true that 10,000 new police officers have been recruited in France xi?

Where things get complicated is when journalists claim to separate the false from the true on more complex issues, subject to nuance, criticism of source data or the prism of opinion.

Frugal fact-checking

It is quite striking that many fact-checking articles published in the mass media lack consistency in citing sources.

Take this article published by RTL xii. The only links it contains are to other posts on the channel. Not a single scientific source is provided. At most, there is a reference to the WHO, which is said to advise against prescribing ivermectin, without specifying that this position is provisional, “until more data are available” xiii.

In this article dated 16 July 2021, the television station RTL brushes aside a medical option with a wave of the hand… without referring to a single scientific study, when there are dozens of them.

Some fact-checkers will do the same job with a little more consistency, for example through this article signed by the decoders of Le Monde and dated 13 April 2021 xiv. Has the question of the effectiveness of ivermectin been reliably answered?

This is not the view of the author of a well-sourced article published on 15 April 2021 on Mediapart xv, which offers a robust critique of the so-called fact-checking of Le Monde‘s decoders. The article refers in turn to multiple clinical trials, meta-analyses, systematic reviews, epidemiological studies, benefit-risk analyses, legal bases, and attaches a bibliography of 33 peer-to-peer articles.

Meanwhile, as of July 2021, more studies and meta-analyses on ivermectin continue to be published. In any case, there are many more scientific references than the two or three studies mentioned by Le Monde when it claims to summarise the question “On what do they base their defence of ivermectin?” To speak of frugal fact-checking does not seem to me to be an exaggeration.

Note the highly emotional rhetoric of the Le Monde article, which uses words clearly likely to discredit the approach of the scientists studying therapeutic alternatives to the vaccine: “miracle treatment”, “therapeutic mirage”… this is how the solution is presented from the outset. From the very title, the story becomes emotional, which is rather paradoxical for a fact-checker.

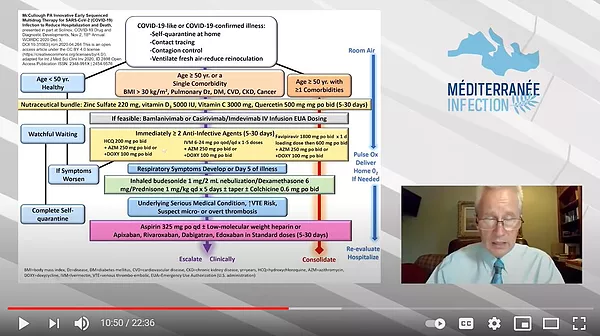

Moreover, the initial question is often insufficient to grasp the complexity of reality. In this case, the question is not just “Is ivermectin effective? But under what conditions, in what proportions, with what other drugs and at what time is ivermectin effective? This is how scientists such as Didier Raoult and Peter Mc Cullough approach the issue.

Professor Mc Cullough, invited here to the IHU Marseille, explains in detail the medical protocol that he believes is effective.

The drugs are not seen as miracle pills, but they are integrated into a whole medical workflow xvi.

This brings us back to the root of the problem: can we afford to fact-check, in one clear-cut article, complex issues that are the subject of a myriad of studies, parameters and viewpoints?

Paradoxically, it is sometimes in the alternative media, often called “conspiracy lairs”, that you will find the good practices of scientific journalism and the citation of sources. Platforms such as ReinfoCovid regularly conclude their articles with bibliographical references, as in this article on the methods of calculating the effectiveness of vaccines, to give just one example xvii.

Criticism of the feverishness of fact-checking is not reserved for the alternative media or people involved in associations; it is the scientists themselves who sometimes take to the stage to denounce the fragile reasoning of certain journalists.

For example, in June 2021, American scientists sent a criticism to the fact-checking media in the form of an article on the first results of the analysis of deaths reported in the US pharmacovigilance system, called VAERS xviii.

You will find the French translation of this article on the RéinfoCovid website xix. In particular, the researchers denounce significant omissions, such as the fact that the fact-checkers fail to specify that the post-vaccine deaths in the pharmacovigilance databases have not been de-correlated or declared not attributable to the vaccine. Therefore they may be!

The article concludes: “In any case, we believe that fact-checkers should be treated with the same degree of scepticism and distrust that they recommend we employ when we read the sources they so strongly refute.”

Emotional fact-checking

The lightness with which some information is brushed aside by the mainstream media is quite startling. Take this article in Le Nouvel Obs. It announces a major news item: a scientific meta-analysis, based on 18 randomised trials, which concludes that ivermectin is effective in reducing mortality in the face of COVID-19 and in speeding up the recovery of those affected.

Observe the scepticism with which the American Journal of Therapeutics study is greeted by the Obs. A scepticism a priori, totally unsupported on the factual level.

After calling ivermectin a “miracle treatment” (a term that is not claimed in the scientific literature in question), the newspaper multiplies the expressions of scepticism and doubt. An amalgam is then made with the most controversial personalities and themes: Didier Raoult, Donald Trump, Bolsonaro, hydroxychloroquine. But these elements have nothing to do with the subject of the study.

The link to the study itself is… wrong! I searched for it xx. The references on which the study is based are not communicated at all. And neither its content nor its methodology are analysed.

Nor is the mistrust with which the study is received substantiated. No mention is made of a counter-analysis or of experts who would have spoken out against the conclusions of this recent report from the United States.

After casting doubt on the hopefulness of this research, the journalist concludes by referring to the “worst side effects” of ivermectin, adding fear to doubt.

There is no question of fact-checking. One line to announce the study and fifty lines to discredit it. No details on the researchers’ profile, methodology, sample and conclusions.

Other studies have been published in the meantime, in the United States xxi and in France at the Institut Pasteur xxii. But these studies are systematically disparaged xxiii by the mainstream media, which focus on vaccine advocacy.

One-sided fact-checking

The mainstream media sing from the same hymn sheet. And fact-checking is a one-way street. Systematically, reframing leads back to the official position: pro-vaccine, pro-mask, pro-lockdown. The only time problems are brought up is to point out their exceptional nature xxiv. Equally systematically, alternatives to the vaccine are downplayed, as we have seen previously.

Rather than allowing the reader to forge his or her own truth on the basis of a contradictory debate, which in fact exists, fact-checkers take sides. True or false’ signals the death of dialectic and Socratic questioning. We are no longer in a science that researches, but in a science that knows, or claims to know without a doubt. There are good scientists, and bad ones, those who are blacklisted because they do not adhere to the consensus.

This is how Nobel Prize winners or experienced researchers can find themselves, overnight, on the shelf of mad scientists, failing brains or ego-driven scientists, as soon as they no longer fit into the official line of thought.

The list of scientists who have gone mad in 2020 and 2021 (editor’s note: this is irony) is growing. I made a poster with a first selection:

I designed this poster as a wink. A factual study would quickly show that dozens of extremely brilliant profiles have been the subject of a real rampage by the mainstream media. Type their name into a search engine and savour the creativity that some journalists deploy in practising the snake’s tongue and biting the reputation of courageous and brilliant personalities.

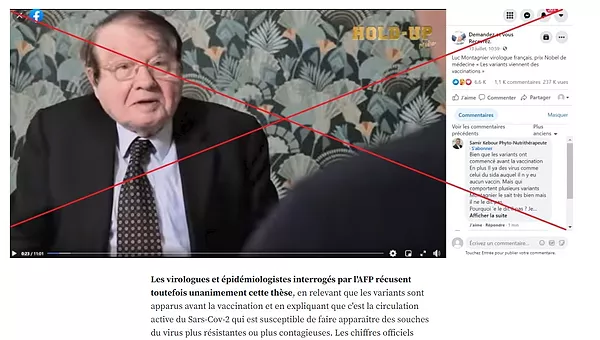

Below, a Nobel Prize winner in medicine is crossed out in red pen by AFP journalists xxv.

The emotional effect of this kind of process of crossing out a person (literally, in this case) rather than crossing out a specific statement, obviously leaves its mark on that person’s reputation. The most critical among us will wonder whether this is not precisely the objective pursued by the ‘watchdogs’ xxvi of mainstream thought: to discredit the very people who have been praised, as soon as their discourse deviates from the consensus.

Note the weak consistency of the argument: “The virologists and epidemiologists interviewed by AFP unanimously reject this thesis.” The experts in question are not cited precisely. It is specified that these are the experts that AFP decided to interview. Fortunately, because if they had interviewed other experts on the same subject, such as Didier Raoult or Kaarle Parikka xxvii, there is a good chance that the aforementioned unanimity would be scratched.

Below, in line with the AFP, the RTBF xxviii frames our Nobel Prize more gently: a rounded “Faky” logo accompanies a photo that has been kindly chosen so as not to highlight Professor Luc Montagnier.

To make sure we have understood correctly, RTBF will add a subtitle on “Professor Montagnier’s mistakes” and another entitled “A Nobel Prize, not a source of absolute truth”… it being understood that you will find the absolute truth in the “Faky Fact Checking” section of your national television station.

Equally symptomatic: the link to the YouTube video, which is no longer available. Logically, in times of censorship, it becomes difficult to refer to divergent actors, if only to discredit them.

RTBF refers to a YouTube video, which has meanwhile been censored. It is becoming difficult to fact-check in some cases, because censorship acts upstream.

We are no longer in the age of debate. The journalist does not position himself as a facilitator of a diversity of opinion. He takes a position. And by the same token, he implies that there is one correct position, and that all others must be discarded.…

I don’t necessarily have a strong opinion on the issues we have discussed (the effectiveness of ivermectin, the number of deaths attributed to the vaccine, the origin of the variants), but I do have the great frustration of not being able to witness a true democratic, open and respectful debate between scientists with different points of view, information and sensitivities.

Would we have discovered anything interesting in science if we had never accepted a different point of view? Would relativity, quantum physics and electricity have emerged if fact-checkers were waiting for Albert Einstein, Max Planck and Thomas Edison at the turn of any non-consensus hypothesis?

Defamatory fact-checking

Increasingly, fact-checking is turning away from its original purpose. Rather than being about verifying a fact, it is mobilised around the reputation of a person.

Let’s take this example from the ‘True or False’ section on the France Info website:

Screen shot of the “Vrai ou fake” section of the France Info website – 24 July 2021. Title of the article: “True or false: Didier Raoult, the career of a decried scientist” xxix.

What exactly is being verified? It is totally vague.

The title makes no clear proposition that can be verified. Do we verify certain elements of Didier Raoult’s scientific career? Do they verify the fact that he is being disparaged? The France Info article has the appearance of a fact-checking piece, which does not state its thesis, the truth to be verified.

In the end, the reader can imply that what is verified is the legitimacy of the person himself: is Didier Raoult… real or fake? Or what should we remember about Didier Raoult’s background?

The article then goes on to say 214 words… 214 words that are supposed to summarise what is legitimate to think about Professor Didier Raoult. The 2-minute video is like a montage of an egocentric and overconfident character. This montage is very ’emotional’ for an article dedicated to fact-checking. It would be very easy, from the dozens of videos of Didier Raoult, to make a montage that, in contrast, would show all the nuance and wisdom of which this same character is capable xxx.

An intertitle then summarises, in seven words, the scientist’s career: “From French idol to rejected scientist”. Neither of these two assertions (“idol of the French” and “rejected scientist”) is supported by facts.

A more detailed analysis would quickly show that these two assertions are totally abusive simplifications. On the one hand, some French people do not consider Didier Raoult an idol at all, and even those who follow him or give him credit are not obliged to sink into idolatry. On the other hand, several eminent scientists continue to support Didier Raoult’s statements, so he is not rejected en bloc by the scientific community. We are not in a black and white reality, but in a much more nuanced scientific debate, despite those who like to rest on a clear-cut truth.

From the point of view of storytelling, we are witnessing what I call ‘the narrative of decay’ or ‘the scientist gone mad’, which we will find applied to other scientists, such as Christian Perronne, Alexandra Henrion [SF note: this woman is an anti-abortionist who has been for some time part of the “Manifs pour tous” movement, which in itself does not mean that some of her information and facts concerning Covid etc. may not be correct] or Luc Montagnier, each time that they present, at the outset, such a credible and consistent track record that it is necessary to discredit them on another level.

In this article, which raises the banner of “true or false”, there is a great inconsistency in the citation of sources: only one link is provided… to an article devoted to the investigation of Didier Raoult at the University of Aix-Marseille. So the fact-checker has chosen to rely on… an ongoing investigation.

No link is provided to :

Didier Raoult’s curriculum vitae xxxi

Didier Raoult’s very detailed book published precisely to defend himself from the media manipulation he claims to be subject to xxxii

The official video channel of the IHU Marseille (which has nearly half a million subscribers and hours of scientific reflection) xxxiii

French and foreign scientists who continue to give Didier Raoult their full support

The reasons why Didier Raoult’s team continues to defend the idea of studying the effects of hydroxychloroquine administered under well-specified conditions of timing and drug combination xxxiv

The many other subjects on which Didier Raoult shares his work or thoughts

Very sparse in objective facts, this article is, on the other hand, flooded with emotional vocabulary: “decried”, “miracle” (x2), “idol” (x2), “rejected” (x2), “fans”, “such assurance”, “very controversial”. We are sailing in the emotional.

In short, this “real or fake” :

starts without identifying a precise fact to be verified ;

is based on few factual elements

contains zero references to the principal concerned;

is flooded with emotional semantics;

conveys a negative image of the person, without counterbalance.

In the background, the approach is very insidious: fact-checking is used to damage a person’s reputation. The overly docile or unavailable reader will easily conclude that… Didier Raoult is not (or no longer) a person to be trusted. Welcome to the era of ‘people-checking’.

It is all the more insidious because the same person can sometimes be right and sometimes wrong, or simply see things from another angle. This shift from fact-checking to checking the legitimacy of a person as a whole is, in my opinion, a real lapse in journalistic integrity.

From the moment that the focus shifts from WHAT to WHO, from the moment that fact-checkers confuse the role of verifying “what is true” with the mission of designating “who is telling the truth”, from the moment that this role is invested in an emotional rather than a factual manner, it is not an exaggeration to speak of an editorial inquisition.

In other places on the France Info website, the discrediting takes place in a more diffuse way. Like on the home page of the “True or Fake” section, where you land on a photo of an anti-vaccine demonstrator holding up a makeshift sign with spelling mistakes.

Screen shot from the “True or false” section of the franceinfo website – 24 July 2021. The choice of image (an improvised sign with a message in broken French) deliberately aims to discredit the opposition.

It goes without saying that the choice of this photo is not neutral and tends to sabotage the credibility of the demonstrations against mandatory vaccination. A photo of a lawyer speaking in front of a crowd of thousands of people would be just as realistic and would convey an entirely different image of the opponents of vaccination.

In this example, the discredit is not on a specific person, but on a group of people or on a point of view. This is the same ambivalence I mentioned earlier: fact-checking claims the legitimacy of factual verification, but drifts into highly emotional communication choices.

Self-contradictory fact-checking

In some cases, fact-checking media contradict themselves in terms of what they themselves have previously published.

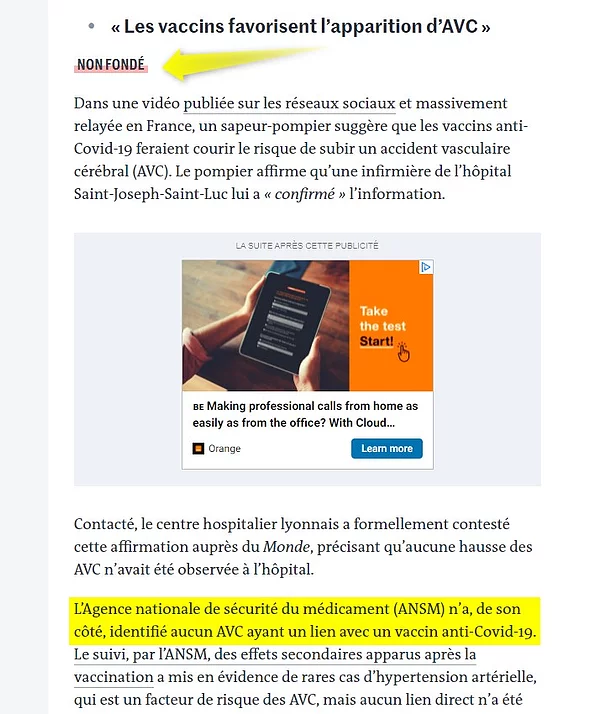

Take the example of the newspaper Le Monde which, on 29 June 2021, pinned down as “unfounded” the fact that COVID vaccines promote strokes xxxv. This statement contradicts their own article published on 26 March 2021 in which they wrote that the French National Agency for the Safety of Medicines confirmed a risk of thrombosis, particularly cerebral thrombosis, associated with the vaccine xxxvi.

The reinfocovid.fr association criticises this example and points out that several other sources attest to the risk of thrombosis, even if this remains infrequent xxxvii.

Extract from the “Les décodeurs” section of the newspaper Le Monde – screen shot dated 24 July 2021.

Above, the decoders point out that the link between the vaccine and strokes is “unfounded”. Further down, it is stated that no stroke has been recorded by the ANSM in connection with the vaccine. However, three months earlier, this risk had already been identified… by the same sources!

In a letter to health professionals in March 2021, says ReinfoCovid, the ANSM reported an association between cerebral venous sinus thrombosis and the AstraZeneca vaccine xxxviii. The Vidal also reports post-vaccine cerebral thrombosis in its article of 18 May 2021 “thrombotic effects of Astrazeneca and Janssen vaccines: what treatment?” xxxix

The contradiction is such that Réinfocovid wonders whether journalists are aware that cerebral thrombosis is in fact a cerebrovascular accident, generally abbreviated as a “stroke”.

It is true that everyone agrees that the risk of thrombosis is very low, but it is not non-existent. This is the great danger of binary “true or false” approaches: they lead to the erasure of nuances and to taking liberties with reality. If we take Le Monde‘s decoding word for word, it is irretrievably false with regard to the same sources.

The reality portrayed by ReinfoCovid may seem more accurate to some: on 12 March 2021, France, like 12 other countries, suspended vaccination with the AstraZeneca vaccine following the recording by the European Medicines Agency of 30 cases of thrombosis (as of 10 March 2021) in the context of pharmacovigilance following the administration of this vaccine. A possible link between thrombosis and this vaccine was recognised on 16 March by the ANSM. Nevertheless, vaccination resumed in France on 19 March with the blessing of the HAS (Haute Autorité de Santé); the vaccine is now reserved for people over 55.

Anti-vaccinators are regularly labelled as “reassurance seekers” or “covidosceptics”, on the pretext that they would minimise the danger linked to COVID-19. But at the other end of the spectrum, governments and the media routinely downplay the danger of vaccines. My point is not to take a position, but to highlight the fact that the communication from both sides is not neutral. The difference is that fact-checkers claim to be the holders of objectivity.

Fact-checking without appeal

In general, fact-checking aims to settle a question and then close the case. The dynamic is “This is not true, don’t talk about it anymore” or “This person is delusional, stop listening to him”.

This is how the RTL article mentioned above xl takes the liberty of stating that the studies on ivermectin are not conclusive and that the WHO advises against its prescription, even though, during the month preceding the publication of the article, research was intensively pursued and new studies emerged.

Not content with insisting that there is no evidence (probably an Anglicism from a clumsy translation of the English) of ivermectin’s effectiveness, the journalist concludes with a sledgehammer that there is not even “any benefit to be expected”.

And since fact-checking is often accompanied by a dose of mockery and disdain, it is pointed out that the treatment was only effective “on 18 golden hamsters”. Clearly, the journalist is not aware of the many much more recent studies on ivermectin. And he buries the debate as one would bury a living person six feet underground, having forgotten to check whether his heart is beating, or worse, wishing not to hear it, that heart of the divergent.

Dramatic fact-checking

In this last part of the article, I use the term ‘dramatic’ in reference to a widely used model in psychology: the Karpman triangle. Because I am convinced that what is fundamentally problematic about fact-checking, beyond the epistemological aspect, is the psychological posture.

Stephen Karpman is a psychiatrist and transactional analysis practitioner who has developed a model to explain ‘psychological games’ that lead to a ‘dramatic’ relationship xli.

He distinguishes three “roles” that we sometimes tend to assume and that will generate unbalanced and painful relationships. These three roles alternate and play out in all directions: saviour, victim and persecutor.

Where does the fact-checker fit into the Karpman triangle?

Decoding: the fact-checker perceives that the poor citizen (VICTIM) is confronted with disinformation. He or she takes on the role of truth teller (SAVIOR) and is prepared to become the great whistleblower (PERSECUTOR) of the perpetrator of the misinformation. The person concerned may, in turn, feel attacked or misunderstood (VICTIM). They may want to react (PERSECUTOR) by fact-checking the fact-checker. The situation may become polarised and the citizen may feel uncomfortable (VICTIM) between these sources of information that say everything and its opposite. In order to stabilise, they may be tempted to take sides, for one or the other (PERSECUTOR). And so on.

You can see that this type of relationship generates tension and disharmony.

In transactional analysis, another model is often presented, that of Eric Berne, which induces 4 relational positions, according to the relationship to oneself and the relationship to the other xlii :

You OK, me OK (this is the recommended position, assertive and open)

You OK, me not OK (this is a submissive position)

You not OK, me OK (this is the position of the persecutor)

You not OK, me not OK (this is a cynical position where nothing is good)

Where does the fact-checker fit into Eric Berne’s model?

By definition, the fact-checker is in the “me OK, you not OK” zone. In other words: I am entrusted with the mission of telling the Truth in a world where some people have it all wrong. This implies, psychologically, that I place myself above others.

I don’t need to show you a picture: this posture leads us straight to dramatic relationships.

In conclusion

Just as one enters the Karpman triangle ‘by wanting to do the right thing’, fact-checking starts from a good feeling, the taste for truth, but very quickly runs into problems.

Among the problems encountered:

Frugal fact-checking, which is not itself based on very consistent sources or reasoning.

Biased fact-checking, which only sheds light on the facts that fit into the accepted lens and only questions experts on one side.

Emotional fact-checking, which gets carried away in inquisition until it forgets its factual purpose.

Defamatory fact-checking, which no longer checks the veracity of information, but attacks the legitimacy of a person.

Binary and definitive fact-checking, which chooses black or white in a world of 50 shades of grey.

Badly outdated fact-checking, when you don’t know what you’re checking anymore.

How high is the Eiffel Tower? How many calories does a kilo of white rice contain? Did President Macron really say this during his presidential address? The answer to these questions will be unequivocal and it will be possible to fact-check them effectively.

Is ivermectin effective? How many deaths are attributable to COVID-19 and how many are attributable to vaccines? What is the origin of the virus? What creates new variants? We are entering a field of nuance and movement, where the truth of some will not be the truth of others, even among scientists.

And when several truths face each other, we have the choice between letting them coexist in an open dialectic (Me OK, You OK), which will perhaps allow us to enrich and adjust ourselves, or we wish to impose a dominant voice (Me OK, You not OK). In this case, we are responsible for creating the polarisation between those who are right and those who are wrong (but will continue to think, out of your sight, that they are right).

Fact-checking has sometimes been presented as an instrument of democracy, on the basis that the citizen has the right to be reliably informed. In reality, it sometimes becomes a tool for imposing the official, dominant or consensual point of view at the expense of a minority who think differently. It is clear that, no matter how good their experience or argument, the minority is discredited and ostracised. In such a scenario, fact-checking becomes, no more and no less, an instrument of totalitarianism.

ii https://www.liberation.fr/france/2019/01/24/les-francais-font-de-moins-en-moins-confiance-aux-medias-d-information_1704808/

iii https://www.clemi.fr/fr/ressources/nos-ressources-pedagogiques/ressources-pedagogiques/le-fact-checking-ou-journalisme-de-verification.html

vii https://www.francetvinfo.fr/replay-radio/le-vrai-du-faux/le-vrai-du-faux-non-albert-einstein-n-est-pas-l-auteur-d-une-phrase-connue-sur-les-abeilles_2416553.html

viii https://www.20minutes.fr/politique/2667719-20191205-attention-fausse-citation-emmanuel-macron-budget-cadeaux-noel

ix https://www.lemonde.fr/les-decodeurs/article/2021/06/29/aucune-compagnie-aerienne-n-interdit-aux-personnes-vaccinees-de-prendre-l-avion_6086229_4355770.html

x https://www.lemonde.fr/les-decodeurs/article/2021/06/29/aucune-compagnie-aerienne-n-interdit-aux-personnes-vaccinees-de-prendre-l-avion_6086229_4355770.html

xi https://www.lemonde.fr/les-decodeurs/article/2018/08/01/non-45-000-eglises-ne-sont-pas-menacees-de-demolition-en-france_5338143_4355770.html

xii https://www.lemonde.fr/les-decodeurs/article/2021/05/12/recrutement-de-10-000-policiers-et-gendarmes-durant-le-quinquennat-le-gouvernement-pas-si-loin-du-compte_6079990_4355770.html

xiii https://www.rtl.fr/actu/bien-etre/coronavirus-l-ivermectine-est-elle-efficace-contre-le-virus-7900055084

xiv https://www.who.int/fr/news-room/feature-stories/detail/who-advises-that-ivermectin-only-be-used-to-treat-covid-19-within-clinical-trials

xv https://www.lemonde.fr/les-decodeurs/article/2021/04/13/l-ivermectine-traitement-miracle-contre-le-covid-19-ou-mirage-therapeutique_6076630_4355770.html

xvi https://blogs.mediapart.fr/enzo-lolo/blog/150421/covid-19-les-decodeurs-du-monde-sur-livermectine-decryptage

xix https://www.researchgate.net/publication/352837543_Analysis_of_COVID-19_vaccine_death_reports_from_the_Vaccine_Adverse_Events_Reporting_System_VAERS_Database_Interim_Results_and_Analysis

xx https://reinfocovid.fr/science/des-scientifiques-adressent-une-critique-aux-fact-checkers-et-a-certains-journalistes/

xxi https://journals.lww.com/americantherapeutics/fulltext/2021/06000/review_of_the_emerging_evidence_demonstrating_the.4.aspx

xxii https://journals.lww.com/americantherapeutics/Fulltext/2021/08000/Ivermectin_for_Prevention_and_Treatment_of.7.aspx

xxiii https://www.pasteur.fr/fr/espace-presse/documents-presse/ivermectine-attenue-symptomes-covid-19-modele-animal

xxiv https://www.lefigaro.fr/sciences/covid-19-l-ivermectine-traitement-miracle-ou-enieme-fausse-piste-20210715

xxv https://www.rtbf.be/info/societe/detail_coronavirus-deux-deces-en-belgique-sont-probablement-lies-a-l-administration-du-vaccin-selon-l-afmps

xxvi https://factuel.afp.com/http%253A%252F%252Fdoc.afp.com%252F9FC93L-1

Reference to the documentary film “Les nouveaux chiens de garde”, directed by Gilles Balbastre and Yannick Kergoat.

xxviii https://www.rtbf.be/info/dossier/faky-fact-checking/detail_non-les-vaccins-contre-le-covid-19-ne-creent-pas-des-variants-comme-l-affirme-un-ancien-prix-nobel?id=10764833

xxix https://www.francetvinfo.fr/sante/maladie/coronavirus/chloroquine/vrai-ou-fake-didier-raoult-le-parcours-d-un-scientifique-decrie_4667341.html

My aim is not to defend Didier Raoult, but to shed light on the journalist’s subjectivity

xxxiv https://www.lemonde.fr/les-decodeurs/article/2021/05/28/tests-sur-les-animaux-risques-d-avc-apparition-de-variants-le-tour-des-nouvelles-rumeurs-sur-les-vaccins_6081873_4355770.html

xxxv https://www.lemonde.fr/sante/article/2021/03/26/vaccin-astrazeneca-l-existence-d-un-risque-rare-de-thrombose-confirmee-par-l-agence-nationale-de-securite-du-medicament_6074628_1651302.html

xxxviii https://www.vidal.fr/actualites/27117-effets-thrombotiques-des-vaccins-astrazeneca-et-janssen-quelle-prise-en-charge.html

xxxix https://www.rtl.fr/actu/bien-etre/coronavirus-l-ivermectine-est-elle-efficace-contre-le-virus-7900055084