Preamble

Unlike most of the reflections on the strike 20 years after, and on the history of miners struggles in general, its aim is to contribute to developing an analysis of the strike and the present day situation in Britain in order to extract a few pointers to a possible future practical use, just as analyses of, for example, the Spanish Revolution (1936-37), contributed to a supercession of anarchist ideology and an attack on Stalinism. In the present desert of practical opposition to this increasingly suicidal world, this may seem over-ambitious. But if you don’t aim high you always end up low.

Although I sometimes use “we”, this text has essentially been put together by just one person, though with considerable help, advice, and encouragement from a good friend.

Chapter 1:

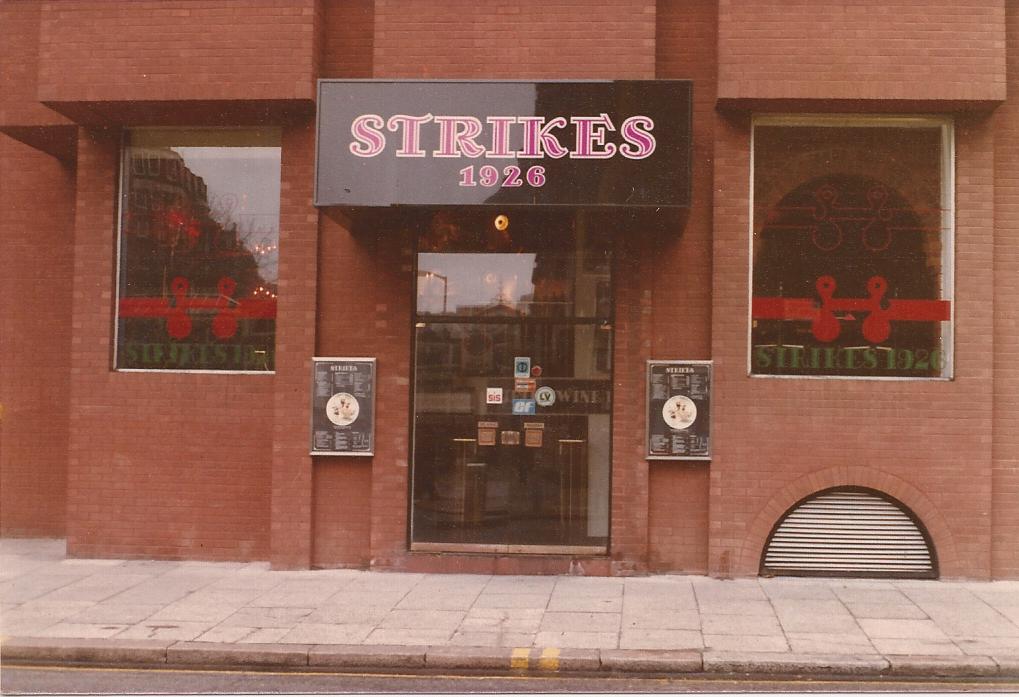

1926 to the early 60s:

The General Strike…Spencerism…A.J.Cook and the project of nationalisation…World War II… Nationalisation…wildcats against the NUM…Industrial capital v. Finance capital…

Chapter 2:

A True Story of A Young Miner in the 60s.

Chapter 3:

The Late 60s to early 70s:

1969 wildcats…In Place Of Strife…1970 wildcats…

Chapter 4:

A Look at Dave Douglass’s View of Miners Trade Union History Up Till The’72 Strike

The 1972 Miners Strike

Chapter 6:

1973 – 1980:

1974 strike…a conversation with miners…Labour government…Benn helps divide miners…Tory plan for defeating working class…

Chapter 7:

The 1980 Steel Strike.

Chapter 8:

1980 – 1983:

Tories test water…’All Lies’ leaflet…NUM collaborates in closures…

Chapter 9:

The Printworkers Struggle At Warrington, 1983.

Chapter 10:

The run-up to the Great Strike.

Chapter 11:

March – April 1984:

The ‘inevitable’ strike…from wildcat strike to official strike…ballots and bourgeois democracy… cop repression…killing of David Jones…imaginative actions…Ravenscraig… Edlington schoolkids…’Misery of Unions’ leaflet & the Barcelona dockers…

Chapter 12:

May- June 1984:

More imaginative actions…Orgreave…Central London comes to halt…Maltby riot…shops looted…

Chapter 13:

Beginning of July 1984:

The text “Miner Conflicts – Major Contradictions”.

Chapter 14:

July – August 1984:

1st dockers strike…Fitzwilliam riot…hit squads and more local riots…

Chapter 15:

September – October 1984:

2nd dockers strike…TUC Brighton Conference…pathetic Leftism…niceness and urgency…Contradictions of the NUM….More attacks on NCB property and on cops…Thatcher almost caves in…IRA bombs Thatcher… unpublished leaflet…NACODS and the almost strike…MI5’s dirty tricks…Thatcher almost lost…almost almost…

Chapter 16:

November – beginning of December 1984:

A divided ruling class…NCB bribe…more rage against the State…Willis attacked…NCB figures for scabbing…death of scab driver …Kinnock…discussion on class violence…

Chapter 17:

The Last Three Months – December to beginning of March:

Collections, charity and the Band Aid spectacle…strikers Christmas…Snow fun…Power cuts…the subtle sell-out…contradictions of low level NUM officials…increasing scabbing…Tony Benn…indifference towards the strike…Paul Foot…the bitter end…

Chapter 18:

The End of the Strike – March 1985

Chapter 19:

The Period Up To The Present.

Chapter 20:

Now and the Future:

Atmosphere in pit villages…media images of strike…gang psychosis of daily life…suicide…comparisons with France…

All useful, radical, analysis of the history of class struggle comes down to recognising how we, the masses of individuals, failed to make that leap in the past so as to ” learn the lessons ” of this failure in order to help make that leap in some possible future (whether it be next week or in ten years time). However, the miners strike was unique and such an opportunity will not arise in anything like such historical circumstances ever again: history does not repeat itself at this level, but clarifying the past is a necessary moment in helping us see and confront the present afresh. It’s certainly not essential in itself but such reflection is one of the essentials. Sure, we have some misgivings about writing about the history of the miners, and in particular, the Great Strike, when there are very few miners left. It’s a bit like fighting ghosts – even though the ’84-’85 strike haunts us in the present, it’s clearly also dead.

For some, recounting these past details of a semi-revolutionary movement might seem like pornography for the celibate – a vicarious pleasure in past passions to console for the lack of real excitement between people in the present. So if it doesn’t incite something really good between people, then much of this is not much better than an erotic memory. For this reason, we hope that this is not just treated as a curiosity, informative and interesting to read: we hope it will have some use – sometimes in its general insights, sometimes in its details, for people in the world (if not in the UK for the moment) who might yet find – or put – themselves in a situation of mass struggle, even though obviously no struggle is ever the same. We trust that there will be some things in this text, and not just banalities (e.g. a critique of trade unions), which are still applicable for other places in another epoch.

What is the relation of the past to the present? Marx famously said “the traditions of the past weigh like a nightmare on the brains of the living”.

Clearly, analysis of the past and of your relation to it is part of breaking through to a more experimental and subversive life in the present. But, contrary to what radical historians say, you only begin to understand the past, to uncover and use it, when you attack the present. Psychologists claim an individual must first of all understand their past in order to supercede it. But this is a task without end and if one is always looking for the cause one remains stuck in an introspective retreat from action. Moreover, one only discovers which aspects of the past need to be focussed on in finding out how to use this knowledge in the present, in confronting the obstacles to one’s desires. What’s true of individuals’ pasts is also true for the pasts of the masses of individuals, the pasts of social movements. So, even on the level of preparing for an attack to come, the extent to which a thorough critical knowledge of struggles from 20 years ago plays a part is fairly tenuous. Though some general and even very specific lessons can certainly be applied to possible present and future struggles, such knowledge doesn’t play the essential part – the essential theories relate to events which can be influenced by the theories – anyone can be ‘right’ 20 years too late. Theory in the present is always made on the hoof: sadly, so many of those that claim to be revolutionary think they can wait till a struggle is over before they can provide some analysis, because they are fearful of making mistakes. Maybe better late than never, but like those involved directly in the practical risks of the moment, far better to make new mistakes with all the risks of imperfection they entail, than to wait till it all becomes a largely abstract question. For this reason, amongst others, this text should have been written in the few years after the strike, when such a reflection could have influenced miners when there still were some (although it was very difficult to see clearly the enormous extent of the coming devastation until it was too late). In fact, one of the main reasons for writing this is to feed a subjective need: to help exorcise the obsession of the miners strike that has churned through my head – and other people’s – for the last 20 years, to off-load the traditions of the past weighing like a nightmare on my brain. Of course, as I have just said, the limitations of psychoanalysis show that obsessions can only seriously be exorcised by some practical supercession. And most of the essential aspects of practice depend on not so much just individual will (say, by writing this bit of critical history, for example) but on the will of the masses of individuals, on a social will, which advances and – at this moment in history – enormously retreats. For this reason this writing will have achieved some real exorcism only by influencing the mass action of individuals a little. Ambitious maybe, but this would be the only satisfactory overcoming of the constant niggles that the miners failure still causes people, because the results of this failure are still in the world about us and still desperately need to be corrected. There is no ‘moving on’, to use the psychological buzz word beloved by our beloved Prime Minister, until the practical situation is changed.

The effects of the miners’ defeat were global. Just as it severely weakened and demoralised the working class, particularly in Britain, so it boosted the confidence of the ruling class immeasurably, and was one of the major factors ushering in privatization, the roll-back of the welfare state and all the horrors of a world apparently without exit. To show the truth of this it’s sufficient to point out that in the budget immediately following the strike, Nigel Lawson, the then Chancellor of the Exchequer, reduced the threshold of top income tax to 40%, an unprecedented rise in income for the rich paid for by cutbacks to those at the other end of the hierarchy.

The present evaporation of community and intensified isolation and reification would have been very unlikely if the miners had won. You only have to look at the brutality of everyday life in the former mining communities themselves to see that. Nowadays these areas suffer from a big increase in:

– burglary and muggings by the young of the old in areas which, up till 1985, had no experience of mugging, areas where people regularly left their front doors unlocked even as late as the 80s,

– alcoholism and drug addiction rife

– general suicidal tendencies and nervous breakdowns amongst the old and young

– intensified domestication – everyone indoors.

– intensified madness of all varieties.

And all this taking place in a booming economy:

– property prices soaring

– a building boom for middle income housing

– gentrification

– the transformation of pit villages into functional dormitory towns for the larger close-by cities

– pretty good wages amongst the skilled working class compared with the past

– scary poverty for the rest, though with relatively low unemployment levels, compared with the 80s.

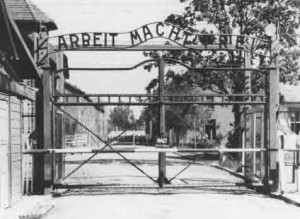

As virtually everybody reading this will know, these tendencies are by no means confined to the former mining areas, though they seem to be more intensified there. Whilst the defeat of 1926 was brutal, the difference between now and then is that in the aftermath of 1926, an aftermath which lasted generations, there was at least a community of class hatred towards the ruling class and its middle class minions. Nowadays, particularly amongst most of the young, there’s just an individual consciousness perplexed by the meaninglessness of life and at a loss to comprehend the reason and history of this meaninglessness. This society tries to wipe out all memory of what was radical in these former communities – either by aestheticisation (former pithead winding wheels turned into sculptures; pits made invisible by being covered over and turned into parks; pits turned into museums for tourists; the Battle of Orgreave re-enacted by historic societies; movies showing the tragedy of it all; etc.) or by more direct lies, lies by omission and ideologies.

the aestheticisation of history (Kiveton Park today)

the aestheticisation of history (Kiveton Park today)

If ‘lessons’ are to be learnt from past and present movements we must look not just at the ruling classes’ strategy – but, more importantly, at the weaknesses and contradictions in the opposition, as well as its strengths. In relation to the miners strike this involves looking not just at the Thatcher government, the National Coal Board, the cops, the media and the Trade Unions but also the failures of the more independent miners, of revolutionaries and of the rest of the working class, as well as their strengths – their audacity, initiative and solidarity.

Amongst the failures on our side we could list:

– the inordinate respect for leaders big and small

– Trade Unionism as an ideological and practical Trojan Horse amongst the working class

– the failure to involve the more passive striking miners

–the failure to make connections between miners and other workers in their workplace

– the increasing indifference towards the strike amongst many who initially identified with it

– the failure of many of those who identified with it to push for their own demands and desires, treating the miners as heroes who could save them

– the demoralising weight of the confusions of the pseudo-revolutionaries in the political groups and parties

–the failure of theoretically sussed revolutionaries to initiate practical activity that would advance their project in a historical situation that made everything so more vital.

All these aspects interacted and it’s only those who don’t want to look to themselves as well as external factors, and the relationship between themselves and the objective forces encouraging defeat, who become experts in reducing the defeat to one or two things.

The good side of the strike was that it got the ruling class very rattled because we almost won, and almost won a very violent confrontation which developed significant radical changes to the daily lives of those who were involved in it. It could only have won if it had developed its most radical autonomous aspects.

We have not given references because references are a way of seeming correctly researched and objective in a University sense, and passes the buck of responsibility for the facts onto the references: if the facts are wrong you can blame the references. In any case, very few people check references – for academics it’s enough to give the appearance of a factual basis for what one writes and most people, out of blind deference, respect the ‘objective’ nature of what is written. Suffice to say, we have done our best to ensure that the facts we put in here are accurate, but sometimes the information we have kept is sketchy and at times contradictory: so, occasionally dates, numbers and places might not be entirely correct. We have been here neither “economical” with the truth nor the other way – excessively ‘lavish’ with the ‘truth’. Invention would distract from our aim.

Up until 1984, and even up till the savage destruction of the pits in the early 90s, coalmining ”communities” were very closely-knit places. The social clubs were always very well-attended. Almost everyone knew everyone else. Tens of thousands of families had men working in the pits for three or four generations. The fact that it was one of the more filthy, dangerous and undesirable jobs as compared with the jobs done by most of their fellow wage-labourers, and that it was essential for the running of the economy, meant that the struggles of pit ‘communities’ were more central than most other struggles. The miners were not a ‘vanguard’ of the proletariat, but often their struggles were the fiercest and most inspiring. They remembered the history of their “section” of the proletariat more than did any other “section”, even if this was often (though certainly not always) from an uncritical contemplative perspective. For the moment we won’t go into what was undoubtedly partly repressive in some aspects of the history of these ‘communities’. Their most publicly significant moments are what concerns us here. It is a rich but (inevitably) contradictory history.

In the struggle to make sense of the past for some future use, there is a fundamental difference between the perspective which defends a particular organisation and a perspective which looks at the strengths and weaknesses in the organisation of the struggle itself. A reflection on the the contradictions in the struggles of each individual proletarian is fundamentally different from a partisan ‘reflection’ used to evasively defend an organisation of which one is a member. Leftist specialists in trade union history tend to only look at the miners from a distorted NUM angle that wants to crudely represent this history by mythologising everything, simplifying everything – a way of looking at history that’s usually been nurtured by a union-subsidised stint at Ruskin College. Its aim is to present and justify a trade unionist role as compatible with a subversion of this society, as genuinely ‘socialist’. For ourselves, we shall try to look at some of the things they don’t even mention.

– John Dennis, Yorkshire miner who died in May 2002.

***

1926 to the early 60s

The General Strike…Spencerism…

…A.J.Cook and the project of nationalisation…World War II…

…Nationalisation…wildcats against the NUM…

…Industrial capital v. Finance capital…

In May 1926 the miners struggle against wage-cuts and increased hours sparked off the General Strike. The bosses, the Tory Government and the TUC combined to break the strike, aided to a certain extent by the miners allowing the Union (the Miners Federation) to isolate them and calm them down. Though it was a powerful strike – in some areas workers militias were formed, and improvised locally initiated Councils of Action were created – it was defeated primarily by a faith in Trade Unionism, and above all by a faith in leadership, which prevented the working class from seeing and extending what they’d already done. Namely, the fact that there were more workers on strike after the TUC had called off the General Strike than before, was not understood by the strikers as significant (perhaps most didn’t even know about it) and the habit of looking to leaders meant that workers quickly returned to work. The essential reason for its defeat is also one of the essential reasons for the defeat of most subsequent struggles: the failure to go beyond the Trade Union hierarchical form, to consciously attack this form. J.R.Clynes, one of the Trade Union leaders at the time, said in his memoirs, “No General Strike was ever planned or seriously planned as an act of Trade Union policy. I told my union in April, that such a strike would be a national disaster…We were against the stoppage, not in favour of it”. Despite this failure, the General Strike still had a significant effect on the working of capital: for example, nine days of just 1% of normal train services running “caused chaos on the railways for months afterwards. The breakdown was greater than that caused by the air-raids on London in 1940-41 and took much longer to repair.” (Tom Brown,The Social General Strike).

The miners themselves continued to strike for over 7 months after the General Strike but in almost total isolation. Due to lack of support, combined with poverty and starvation (though, as in the Great Strike almost 60 years later, soup and meals were provided, and there were collections through benefit concerts), the strikers were humiliated back to work.

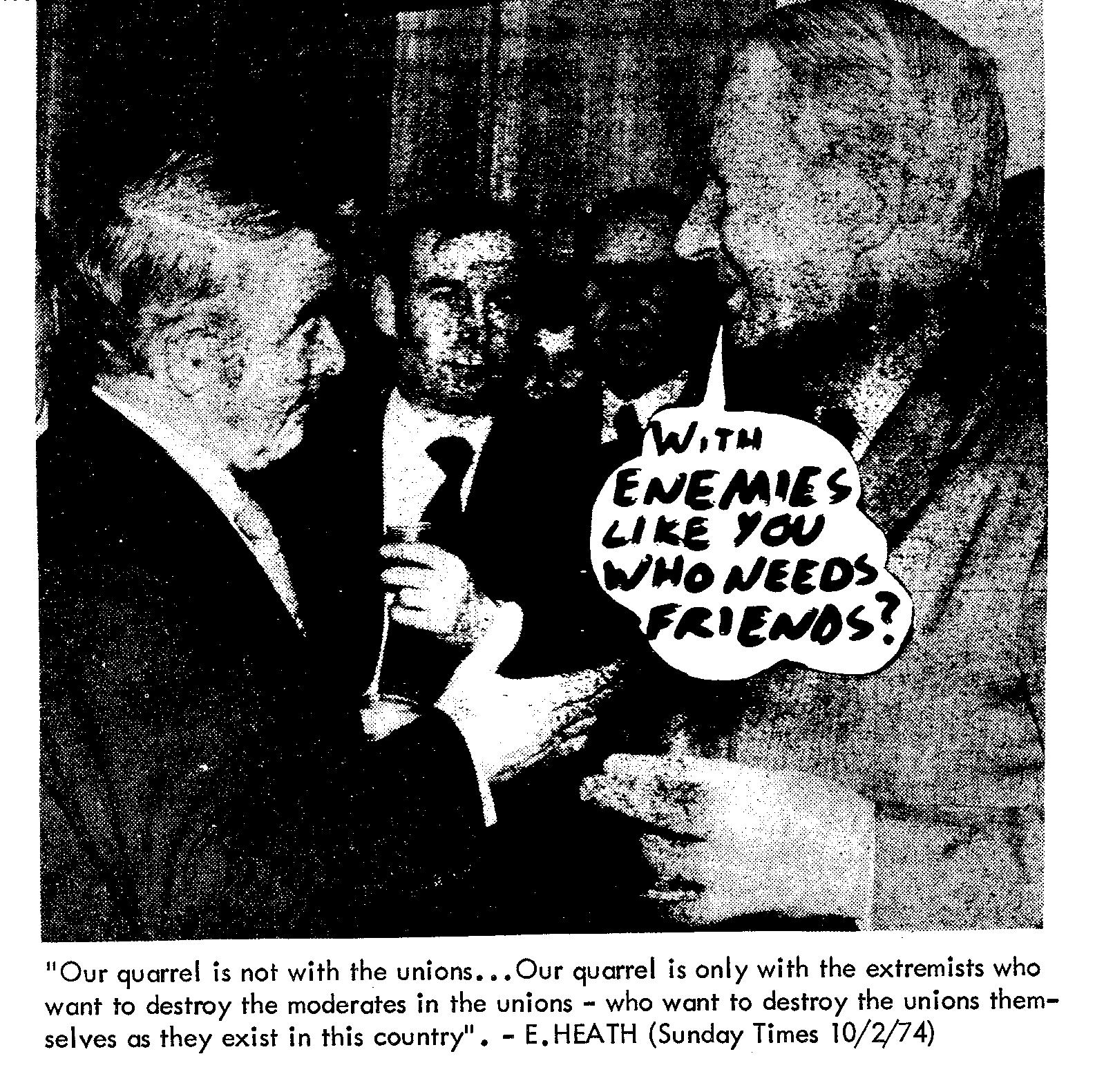

Ready – Steady – Cook (during the General Strike)…

Ready – Steady – Cook (during the General Strike)…

…those who make arfur revolution dig naught but their own graves…

The miners were led by the famous A.J.Cook, the “revolutionary” leader of the Miners Federation [1a] (the forerunner of the NUM), the first miners’ Arthur, whose image is as much a legend as the King some people have treated him as. A.J. Cook was undoubtedly a good passionate speaker. Though he was paid as a Union official, he was never a full-time bureaucrat; he worked alongside the miners he represented – all of which is why he was uncritically supported by the vast majority of the miners of his time. But he was very much an expression of the weakness of the old workers movement, and believed, amongst other things, in professional paid leadership and whose idea of justice for miners was simply nationalisation. Moreover, he insisted that miners weren’t lazy and that they were not saboteurs (see The Case For The Miners, written by Cook, pubd. 1924). It’s very much part of the schizoid leadership role within this society, especially within trade unionism, to present a ‘reasonable’ (reformist) image to the general public, whilst rabble rousing to your followers. He was briefly a member of the CP, having left in 1921, probably because being a CP member would have prevented him from being elected as miners leader (according to Paul Foot, anyway). Certainly there was nothing particularly principled about his departure and, unlike for example Sylvia Pankhurst or Anton Pannekoek, he never incurred the wrath of the international or national CP, and indeed was praised after his death by Arthur Horner (the leading Stalinist miner’s bureaucrat who insured that the miiners buckled down to the State as boss of the new nationalised mining industry after World War ll). He remained a member of the ILP (one of the best of the old workers’ movement parties), but was never one of the more independent-minded members.

As for nationalisation, in Britain at least, nationalisation was never considered a particularly socialist, let alone radical, idea. The Sankey Commission into the mining industry which published its findings in 1919, recommended “nationalisation or a method of unification by national purchase and/or join control”. This Commission included a Tory member of the government – Andrew Bonar Law, who later became Prime Minister for a short time. Undoubtedly this recommendation came as a verbal sop to the workers movement which, in the wake of the October Revolution in Russia, was growing more confident. The Miners Federation accepted the Sankey Commission’s findings without question, which shows how easily recuperated the British workers movement was at this moment. Of course, its findings weren’t put into effect until almost 30 years later. Regardless of its words, in practice the British ruling class rarely makes concessions of any significance until well after the social pressures to make concessions have receded. It doesn’t like to be seen to be giving in. Shortly before the General Strike, a different Royal Commission – the Samuel Commission – reported recommendations which were a retreat from the suggestion of full nationalisation, suggesting only that coal royalties be nationalised, recommending the continuation of private ownership with a few minor concessions thrown in – pit head baths, and improved government aid for research and distribution. Despite the fact that it suggested immediate consideration be given to the lowering of wages (some months into the miners strike, but after the defeat of the General Strike) the great radical A.J.Cook said the miners would accept its findings. But even then, the mine owners, the balance of class forces having been firmly tipped in their favour, refused to accept even its very minor concessions. Which just goes to show that, even on the level of ideas, to concede anything to the dominant powers will, rightly, be taken as a sign of weakness, and, as is the case when confronted with mad dogs, only encourages further attacks.

During this strike, George Spencer, a Labour M.P. 1b , was instrumental in forming an openly scab union in Nottinghamshire which signed a local agreement which was rather like Franco’s model of unions, which later on got some support in most other mining areas. Areas were picked off individually for lower wages because the owners knew that if there was a strike in one area, coal could still be mined in another. In the aftermath of the wildcat strikes after the TUC called off the official General Strike, the Tory government made wildcats illegal. In 1936, some Notts miners, despite being in the Spencerite scab union, were sent to prison for going on wildcat strike.

During the early 30s, parts of the left-wing of capital wanted the coal industry to be run by a “mining council” with 10 State-appointed members and 10 union-appointed ones, which had already been proposed by union bureaucrats from 1912 to the late 20s. Whilst in the Labour Party, Mosley, a Keynesian at this time, had put forward a Manifesto proposing temporary deficit financing for public works and protectionist imperialism, which was signed by 17 people – 16 Labour MPs and A.J.Cook. This was later demagogicly taken up by Mosley’s fascists.

The temporary State management (not ownership) of the pits during World War ll didn’t stop trouble at the pits despite strikes being made illegal (”without State permission”). State management during wartime meant a worsening of conditions: safety regulations were suspended, overtime was made compulsory and, with increasing amounts of miners being made unemployed, miners who were still employed were made to work harder. In 1942 there were wildcat strikes in Yorkshire and elsewhere. In Betteshanger, Kent, over a thousand miners appeared in court for striking contrary to wartime law. All were found guilty and fined, three being imprisoned (unlike Lady Mosley during the war, however, they were not allowed to have their butler in prison to cater to their every whim).

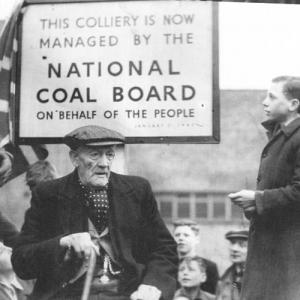

On January 1st 1947, the pits were nationalised with the post-war Labour government in power, who were conscious of the need to grant concessions for the securing of social peace in the wake of general increased expectations in the post-war era – and the National Coal Board (NCB) came into existence. Emmanuel Shinwell, a former radical jailed during “Red Clyde”, the semi-revolutionary atmosphere in parts of Scotland after World War l, who later became Lord Shinwell, presided, as Minister of Fuel and Power, over the nauseating nationalistic ceremonies under the banner of the virtually Stalinist slogan, “The National Coal Board now owns and manages the industry on behalf of the people.” 2a On the NCB of 9 men, 3 were ex-mine owners (amongst them, Lord Hyndley, former president of the Company of Mines) and 2 were high level Union bureaucrats – Ebby Edwards (in charge of labour relations) and Lord Citrine, an old enemy of the miners who, as acting General Secretary of the TUC in 1926, had sold them out. The National Union of Miners (NUM), born 2 years previously, pledged itself to “do everything possible to promote and maintain a spirit of self-discipline…and a readiness to carry out all reasonable orders given by management.”It had no formal representation on the Board but the NCB labour department, the day-to-day cops of wage labour, was staffed largely by their own ex-officials. Many regional officers of the union took up jobs with the NCB but the NUM’s rules forbade them to keep up their formal union membership. Miners themselves didn’t seem to have many illusions in the new Board. As early as summer ’47, a delegate at the annual NUM conference warned against “the terrible tendency to paint the face of the coal-owners over the face of the Coal Board.”

After 1947, both the NCB and the NUM were finding it difficult to generate “the new responsibility” which Arthur Horner, the NUM General Secretary who was also a leading light in theCommunist Party [2b]., wished for. The National Reference Tribunal (mandatorily binding arbitration) was excitedly praised by the NCB who hoped “to infuse a new spirit into management and men, new partners” and by Horner, who thought it “would achieve the maximum results for our own forces with the least possible damage to them”. The NUM used all the influence it could muster to ensure restraint in wage negotiations. As Horner said, “If we asked for the moon, we could get it. Instead we have shown the highest sense of social responsiblity of any organisation in this country”. Translated this means: “The miners have enormous potential power – but the NUM, as a capitalist organisation responsible to this society and the country/nation, has shown its ability to defuse that power.”

After 7 months of nationalisation some of “the people” came into conflict with the organisation which acted on their behalf – a wildcat strike broke out at Grimethorpe which was described by one union leader as the most bitter he had ever seen. The NCB wanted a 5-day week, but wanted to reorganise shifts so that the extra production which used to be done on Saturdays was compensated for by an increased workload during the week. The NUM opposed the strike. Within 3 weeks it spread to 38 pits and the Yorkshire Area General Secretary told the men to choose “between industrial democracy and anarchy”. Will Lawther, ex-President of the General Council of the TUC and an NUM bureaucrat, said that the NCB should prosecute the strikers“even if there are 50,000 or 100,000 of them” and he attacked strikers for not recognising “their responsibilities” and for committing a “crime against our own people”. Strikers at Grimethorpe responded by painting a gallows outside the colliery gates with the slogan“Burn Will Lawther”. Shinwell pleaded that many Yorkshire firms could go bankrupt if the strike continued and Horner warned that the shortage of coal could bring down the Labour Government. The union signed an agreement with the bosses promising “to prevent unconstitutional stoppages” and to prohibit any financial or verbal support to strikers in such stoppages, whilst the NCB took 40 miners to court who were penalised for damages under a law passed in 1875. In the year after nationalisation miners strikes accounted for 33% of days lost (lost to capital that is – but gained by the workers) through strikes that year. Miners were just 4% of the workforce.

It’s significant that Lawther was knighted by the Queen a year or so after the above mentioned strike. Later, in July 1953, he said in a speech to the Durham Colliery Mechanics’ Association:

“We cannot afford to be Luddites…We must rebuild this nation to be as formidable in this century as in the past. This cannot be achieved by following people who are always cursing the land of their birth and speaking as if we are among those countries who never know, when they go to bed at night, who will be in charge in the morning.”

The decade after nationalisation – the period of the most capitalist reconstruction up till that time – nevertheless insured a growth in wages in part due to the combativity of the miners, but also due to Keynesian government policy of full employment which needed to develop proletarians as consumers, and required better health for wage slaves, partly because of the possibility of war constantly in the background. Mechanisation was brought in, and so were free baths, newer canteens, better housing, better compensation for injury, a pension scheme, and better safety conditions (though mechanisation involved the creation of vast amounts of coal dust particles which produced an epidemic of pneumonicosis – a kind of lung cancer). Although production had remained steady up till 1960, manpower had fallen from 704,000 to 602,000, the increase in productivity being mainly down to mechanisation. Moreover, the increase in oil imports from the end of the 50s meant coal production was being increasingly cut and by ’65 there were only 456,000 miners, and by the end of the 60s this had fallen to 287,000, 47% of what it was in 1960, though productivity had risen by 57%.

From ’59 onwards, the NUM, while recognising that “all pits must eventually die”, were warning governments about “the effect on the community” of “premature” shutdowns. The NUM defended capitalist policies in the interests of the NUM – i.e. investment in coal, the more the better. Unions defend their own particular interests within capital – hence the NUM represented a section of industrial capital, unlike banks or financial institutions, which are not concerned with investment in any particular sector 3. Apart from the Unions’ role as police, as negotiators of wage labour, as recuperators, they also have to defend their specific role in the reproduction of capital – because they depend solely on the union dues paid by their members and on the investment of these dues and pension funds. The NUM cannot suddenly relocate to another industry. Hence, in the 60s, both the NUM and the NCB campaigned for a greater consumption of coal on the internal market – both extolling the homely virtues of coal fires. The NCB too had to defend its own position – the defence of the profit-rate of a sector of capital. In 1966, Lord Robens, Chairman of the Coal Board, said “A lot of people in the union attack the Coal Board…I attack the government.”

Formerly on the Left of the Labour Party (he was shadow foreign secretary during the Suez crisis, and considered “too left-wing” by its leader, Hugh Gaitskell) Robens ended up supporting Thatcher in 1979.

Formerly on the Left of the Labour Party (he was shadow foreign secretary during the Suez crisis, and considered “too left-wing” by its leader, Hugh Gaitskell) Robens ended up supporting Thatcher in 1979.

The highpoint of his life was the Aberfan disaster in 1966 when a a massive spoil heap from the nearby Merthyr Vale Colliery collapsed onto the village of Aberfan, burying 20 houses and the Pantglas Junior School in a 10-metre deep landslide of water-saturated slurry, killing 116 school children and 28 adults. The report of the Davies Tribunal which inquired into the disaster was highly critical of the NCB and Robens (the possiblity of such a disaster had been foreseen, but of course, nothing had been done). He eventually appeared in the final days of the inquiry and conceded that the NCB was at fault. In the wake of the disaster Robens refused to allow the NCB to fund the removal of the remaining tips from Aberfan, despite the fact that the Davies Tribunal concluded that the NCB’s liability was “incontestible and uncontested”. Despite this conclusion, Robens refused to pay the full cost. Robens then raided the Disaster Fund (which had been raised by public appeal) for £150,000 (£1.8 million at 2003 prices) to cover the cost of removing the tips – an action that was “unquestionably unlawful” under charity law – yet the Charity Commission took no action to protect the Fund from Robens’s thieving. Those were the days!

Chapter 2

We interrupt this chronology to reproduce a personal account by a miner of a series of incidents in his pit village, which gives some idea of the atmosphere of the mining areas during the mid- 60s. It is not the kind of history one is likely to see from those trained to write “History” with a capital “H”. It is lived personal history.

The Story of a Boat

(no title in the original)

by John Dennis

This story begins in the early sixties. I would be just sixteen years old, just entering the world of work. Life appeared good and for me – everything seemed possible (people of my age are obliged to say that sort of thing about the sixties). Anyway, Europe at that time had a massive mining industry in which millions of people were employed and on which millions depended. We happily polluted the skies with our smoke and denuded the land and forests with our acid rain. The Beatles were beatling and The Stones were beginning to roll. Good whisky was about two pounds a bottle, beer was around seven pence a pint. We teenagers were being trained to provide the hands and minds that would begin to embrace the white heat of technology. Most of us in the mining communities seemed to have a place in the present and great expectations of the future. Ignorance was bliss and we were blissfully ignorant.

For such kids as myself who did not enjoy an above average intelligence or parents with middle-class aspirations we generally gleaned some sort of education from the secondary modern schools. Thus after spending five years learning the rudiments of social interaction, petty crime and sexual experimentation it would be time to leave and be taken into one of the three great soaks of the young white male in Yorkshire. For the majority it would be the mines, the steel industry or the armed forces. If you consider my family history and the proximity of the coal mines – six within a three mile radius and one on the doorstep – it’s not too surprising that I should take what seemed to be the easy option and sign up with the NCB (National Coal Board).

After the primary euphoria of acceptance and a vigorous sixteen week training period a great disappointment befell me and the likes of me. Because we were above six foot in height and weighed less than eleven stones it was deemed that we were physically unsuited to become face workers. It would seem that the ideal face worker should be five feet nine high and five foot six across, social engineering maybe? The shame, all our clan had been underground workers, my father, his father, his father, cousins, brothers, maybe the odd sister, all of them members of that industrial elite, the money, the hours, the social kudos. I was willing to be killed, crippled or rendered lungless, if only I could have carried on the family tradition. Alas, no, so a compromise was made. I would be apprenticed into one or more of the mining trades. In time I would be a blacksmith, welder, farrier, learn the mysteries of rope making and in my spare time make tea for the craftsmen, clean the workshop and not complain if I should be beaten up or sexually abused.

So it went busily on until one dull as dishwater morning in 1964 the foreman came to us and gave us our tasks for the day. He began with the opening, “John, Mick, Alan, you’ve shown such promise in your metalworking skills that the engineer has seen fit to give you lads the chance of a lifetime.” We heard the man’s blatherings with some suspicion but not with optimism, he was Alan’s father after all. What sort of a chance of a lifetime? Some task to test our newly founded skills? Some project in the mine to stretch our physical and mental capacities? Imagine our disbelief when the lickspittle gaffer’s running dog said, “Lads, you’re going to help build the Chief Engineer a sailing boat”.

I think it may be wise at this juncture to explain some of the social relationships between the miners, the village and the employers that existed during the 1960s and 70s. We seemed to be in a period of some consolidation between the barbarities of the coal owners and the savagery about to be unleashed during the Thatcher years. After nationalisation, conditions in the mines improved, poachers turned to game keepers, the NUM incorporated its powers. Investment in mining was massive, there seemed to be a tacit agreement that, “if it was good for the miners it was good for Britain”, and no doubt the miners thought vice versa. In villages such as Kiveton Park with a population of around three thousand, one thousand worked at the mine and seven hundred in mining support industries. The old patrimony seemed to carry on seamlessly. The Dennis family like many more had fled the famine in Ireland during the middle of the 19th century. They had washed up on the shores of this uncompromising land and straightaway signed up to work in one of the most barbaric industries in Europe. Great grandfather John had been a shaft sinker at Kiveton Park, his son John a driver of tunnels. I would be the third and the last John Dennis to work at Kiveton Park Colliery. We lived in low rent houses owned by the NCB. The schools, medical facilities owed their beginnings to the miners, even the churches and chapels were built or renovated by the good will and labour of the workers. We would nowadays be described as a close community.

The hierarchy at the mine itself was only slightly revised from the days of the coal owners. The Colliery Manager could be likened to the captain of a nineteenth century sailing ship, his powers awesome, his responsibilities equally so, described by act of parliament he answered for every life, human or animal, every nut, bolt and cobble of coal, the mine and its environs and to a great degree, the social and economic life of the village in his grasping paws. Directly below him on the ladder to fame and fortune, stood peering up his trouser leg, my boss. The enginewright, to give his job description, would be engineer in charge of the mine. In those days enginewrights had so much room in which to line their pockets and abuse their many powers, but one source of unending conflict between the manager (in charge of overall production) and engineer (in charge of the mode of production) was that machines would be smashed, worn out or sabotaged by the elements in a growing bolshy workforce. From the workers point of view the problem was really simple. It took x number of pounds to buy and maintain a mining machine. It took x number of pounds and two years of valuable time to train a pit pony. The workers earn and maintain their own keep. He or she is not a capital investment. For us the answer was simple. We not only stole the bosses’ materials, we stole their time. To the bosses the machine and the pony were of more value than the workers. Also the government had decreed that machines and animals were tax deductable. In those days we knew exactly where we stood.

We all knew the pedigree of our enginewright and we all knew of his predicament in the year of the boat. In 1964 he would have been around sixty four years old, tired and embittered and certainly fraying at the edges. He had married young to the daughter of a second generation colliery manager. He was at that time a lowly machinist, she a lass of great appetite and social conscience. Naturally his ambitions to be an enginewright were fulfilled. Marrying the boss’s daughter assured that. In fact in his younger days he was considered a rising star and it would only be a short time before he attained a place on the board of directors, owning several mines in that area. Then for him tragedy. His wheel of fortune and fame developed a flat tyre. It was 1947 and those red-in-tooth and claw socialists went and nationalised the mines. No more would marrying the boss’s daughter assure him of a safe passage on his slimy journey from rags to riches. In truth, marrying the boss’s daughter scuppered any chance of furthering his career at all. The reason being the reputation of the father-in-law in question. This creature made Josef Stalin look positively avuncular. During his time as Squire of Waleswood and manager of Brookhouse Pit he took his pleasure by sacking any worker who displeased him then evicting them from their homes. Thuggery, buggery and intimidation were all watchwords. But to cap it all he and the mining company owned all the shops and public houses in the village, so by selling them cheap strong beer and relatively expensive food he entrapped the miners and their families into drunkenness, poverty and debt. Even by his contemporaries he was considered an ineffable bastard which must put him in the same league as (fill this space if you know of anyone that wicked who has not been exposed in the full glare of left-wing historians or the mass media).

Thankfully, “the mills of justice may grind slowly but they grind exceedingly small” and the lousy old sod got his punishment in the true and tried English tradition. Firstly, he was given the options of resign or carry on working, sharpening pencils in some obscure office in deepest Doncaster. If he resigned he would be forced to take approximately ten years wages in lieu of lost earnings. His shares in Waleswood Mining Company would be bought from him at premium prices and his pensions would be paid in cash on the day of his resignation. He died a mere 87 years old in his swimming pool on the island of Antigua, some say from a surfeit of rum and rent boys. His days of shame and exile must have given great satisfaction to those many poor and damaged souls he inflicted such gross inhumanities upon. But worse still our poor enginewright was shuffled to the sidelines, there to waste his remaining years, a frustrated Brunel. His wife, now of independent means, would desert him at least twice in the year to do good works in the East End of London or to sojourn with struggling young artists in the steamier regions of Italy. His children despised him, his colleagues pitied him and we made his life as unhappy as he tried to make ours’.

At times of great despondency he would unburden his woes around the pubs and clubs of the villages. It is said that during one of these two-bottle unburdenings he came upon the idea of building a boat that upon his retirement would take him through the canals and rivers of England and thus escape the miseries of mining and the contempt of his family. The spirits guide us in mysterious ways.

Between the Pit Manager and the enginewright there was an old festering conflict. As an ex-lover of the engineman’s wife the manager knew well his propensity for drink and theft, but the enginewright knew of the manager’s weakness for cooking the figures (which enhanced his bonus) and the fact that bedding another man’s wife would not enhance the happiness of that pillar of the local Methodist community, the manager’s wife.

The dimensions of that boat would be thus: in length 18 feet, in width 6 feet, the mast 16 feet tall, the hull to be made of supermarine plywood, the fitments and fittings to be hand crafted, the engine to be a two litre Coventry Climax converted from the pit potable fire pump, hydraulics and pipe work gratis from Doughty, the labour and time gratis the NCB. It was to be built in the carpenter’s workshop but hidden from prying eyes by a canvas partition.

My tasks from the beginning would be to hand finish all the many copper and brass fitments which would be delivered from the foundry in a rough condition. It’s strange how fortune seems to favour the favoured. In this case it manifested itself in the guise of the foreman carpenter, his war service had been spent in the construction of torpedo boats for the British and US Navy. After five years of bending plywood in some Norfolk backwater he could nearly do it blindfold. The sealords work in mysterious ways.

At the start of the project we didn’t mind the painstaking and repetitive nature of the work, after all there was a certain thrill in taking part in such a scandal. Then there was the fact that much of the work was done outside production time. This meant working Saturday and Sunday, time and a half and double time respectively. Add to this the fact that if we felt like a lazy hour in the workshop we would take a small work piece, place it in the vice and pretend to file or polish it. The foreman would peer over our shoulders, put his finger at the side of his nose, nod sagely, then slope off to pester some other unfortunate.

But alas the novelty began to subside and maybe the work began to suffer as a consequence, or maybe we were beginning to react to the attitude of the enginewright. He was becoming obsessed with the time the work was taking. He would stride down the workshop, arms waving, spittle splashing, eyes popping. “Two hours to polish a bollard, that’s bollocks Dennis!” This hurt. All craftsmen know the adage, “More haste less speed”. It’s imprinted in the back of our minds like a mantra, so we naturally resent such talk.

After work we’d sit in the pub and talk of the really important things such as money, sex, money, Alan’s latest wet dream (they were becoming really bizarre). The things that lad got up to in his sleep would keep a Jungian trick cyclist in work for a lifetime. On the afternoon of the gaffer’s outburst about my bollocking bollards, he related his dream of the night before. It seems he was page boy to the mother of the queen. It involved him guiding the penis of the queen mother’s horse into her vagina (which was tastefully kept from view by a tartan blanket) while he was being masturbated by the young Princess Anne, naked but for a golden miner’s helmet. Bloody hell! Then we’d talk about money again, the advantages of the condom as a device for halting premature ejaculation, the quality of the beer and then finally the boat and how everybody but the bloody enginewright was becoming so disenchanted with the whole bloody project.

Things took an extra turn for the worse a few days later when the enginewright brought his new assistant to the workshops on what could be described as a guided tour, during which he mapped out the pitfalls, snares and traps his prodigy would encounter in his daily dealings with the proletariat. In fact on passing our workbench at which I was putting the final shine onto another (or was it the same?) bollard the old snake said to his new gofer, “Watch that bastard Dennis. He’s idle, shifty and he’d steal the coat off the back of a leper.” I was most offended, shifty indeed! I’d never been called shifty before. This new guy was of old mining stock but had just graduated from Sheffield University. He had the wit to understand the boat situation but from the onset he had made it clear that he would collect feathers in his cap if by hassling, hustling and bustling he could expedite the completion of the “Marie Celeste” (as the boat had now become known to we three apprentices). To these ends this man would be found prowling the workshops at 6.30 in the morning. Management in its senior forms would never be seen before 9a.m. if the good running of any enterprise is to be assured, workers in all walks of life understand this basic tenant. This guy would appear before we’d finished wiping the sleep from our eyes and say in a loud voice, “Right men, let’s show the boss what we can do. Come on, let’s get cracking!” Indeed one morning he said to the foreman, “Get the bollard boys off the boat work and onto some fucking pit work. It’s a bleeding disgrace this workshop.” Imagine the foreman’s shame at being usurped by an overweaning toe rag the likes of an assistant engineer. Also the added shame of having his son described as a “bollard boy”, this epithet was to remain with Alan for many years. In fact to this day when father and son are seen together the cry will go up: “Here comes Blacksmith Bill and his bollard boy,” a remaining stain on a proud working family.

The situation finally came to a head one morning when the assistant discovered the foreman blacksmith trying to fold a piece of canvas into the boot of his car. The assistant with his usual calm and considered approach said, “Right! What do you think you’re doing stealing the Gaffer’s sailcloth?” The blacksmith replied, “This is not a sail, this is a hammock for my back garden, so fuck off”. The assistant stamped his feet, turned pink, turned purple, whipped off his helmet and kicked it across the car park shouting, “Right, that’s it. You’re sacked, fired, I’m going to have you prosecuted.” You may have guessed that by this time everybody called him Mr. Right. But let’s not digress. The assistant went to the manager, the foreman of the Union and the rest of us looked like going on strike.

In 1964, my father and the pit manager would be 53-54 years old. They’d both left school at 14 years of age and had started in the pits as pony drivers, their job to lead the pit ponies pulling the tubs on their journey from the coal face to the collecting points. To the pit bottom it was an arduous and dangerous journey. In those days it was a rigourous training for even harder things to come. Their careers had parallels in time and in some ways circumstances. When I look at photographs of my father as a teenager at 14-15 years old I can see a child but eyes are already ageing beyond his time. His body is that of the small Dennis’s – around 5′ 6″(full grown 5′ 9″), big shoulders, thin waist, long arms and those silly tendril-like fingers that we’d all inherit – except for his hands the perfect mining shape. Early in life George, through the influence of his beloved mother learned to and became a talented violin player. The manager at that same age found that most cherished of Yorkshire sports, cricket.

During the 1926 strike father learned hard lessons about the lack of solidarity of the English workers when threatened by the middle classes. In the late twenties he joined the Communist Party. Our manager in the meantime through his ambitions to rise in mining and his contacts in the higher echelons of cricket became a deputy (underground foreman). Father led a local dance band, the manager led Worksop cricket team and was very active in the North Notts Tory party. They both married in the late 1930’s. The manager left the Tory Party in 1939 because of the appeasement of the Chamberlain government. Father left the Communist Party in 1941 when Stalin signed the non-aggression treaty with Hitler 4. In 1964, father at that time was union secretary, enjoying all the benefits that the position accrued to him, one of which was having intelligence on all the dubious doings of his membership at the mine at that time. Mr. Right had hardly finished his tirade in the car park before father was on his way to the manager’s office with certain cards to lay on the table and a few kept in reserve up his sleeve. His main argument was really direct and to the point. If any action were taken against the foreman blacksmith he’d be on the phone to the area offices describing the scandal of an engineer who seemed to think he was Noah and his upstart assistant who didn’t understand the basic rules of one illegal item for the management meant one for the workers. The manager didn’t even alter his countenance, he just waved his pen in the air and said, “George, what do you expect from a young lad straight from college. Let’s talk about getting a little bit more effort out of these chaps down in the headings.” To father that meant the subject had been settled satisfactorily. Mr. Right was less than satisfied when he was called to the presence later that morning. The information came back to father via the manager’s personal secretary, who was allowed by the manager to hand down information to the workers when the occasion suited. The meat of the interview was as follows. “What do you mean stealing canvas? There’s enough canvas in the stores to fit out the fucking Spanish Armada. Mind your ways laddie or it’s the Scottish coalfields for you”.

Young Mr. Right, a well chastened assistant, was very subdued for long into the future, but still given to uncontrollable helmet kicking when primed and fired by the expert wind-up artists.

Let me explain my piece in the jigsaw. For example, as many as fifteen bollards would arrive at the mine from the foundry. The attachments look like the letter “I”. They are fixed firmly; thereby ropes can be safely tied off and sales and masts can be made secure. Each small brass object would arrive from the foundry in a rough condition. To make it smooth the sharp edges had to be taken off with a very coarse file. Then marks and gouges had to be taken out by a less coarse file until a smooth file could be used to take out those marks, then metal abrasive cloths and then a polish hard and a polish soft. But every time I looked at the boat I was charmed, it’s lines, the work, it was becoming pleasing to the eye and to my mind a pest. For my two friends it may have been worse. The fitting of the engine and the keel would be educational but just as exasperating.

Later that day, showered, needlessly shaved and very thirsty we assembled ourselves at the bar of the Saxon Hotel. There we ordered our beers from one of the few Calvinist barmaids in the county of Yorkshire. She held we youngsters in the deepest contempt saying we were doomed to the fires of hell and damnation due to our drinking, gambling, fornications and foul-mouthed unruly behaviour, then promptly gave us the wrong change (always short) and scream for the landlord if we complained. This woman exercised my curiosity no end. She would wear low cut sweaters hardly hiding her upthrusting breasts, the shortest of mini-skirts, make-up by the kilo and then declaim religion in a manner which would have made Martin Luther King reach for his tape recorder.

In those days we would drink our first two pints standing at the bar (why waste time and energy walking?), order the next round, then find a table away from the jukebox and set about the foul-mouthed repartee which would so inflame the senses of our beloved barmaid. We were thus engaged when in walked father, who with no more ado came up to our table and sat down. “Well lads, I’ve just come from a chat with the manager and Alan’s dad. I think the best solution is for you lads and everybody concerned to get your fingers out and get the bloody thing finished and off the premises as quickly as possible.”

I couldn’t believe my ears. What was he saying? Rush a job which by my crude estimations would, if dragged out for another three months, earn the people involved at least four hundred pounds in overtime let alone hours fruitful pleasure baiting the bosses? No way daddio! I saw his eyes glint and his shoulder muscles hunch when Mick said, “Bollocks! Whose fucking side are you on? Are you up the manager’s arse or something? This is money for old rope and it’s going to last as long as we can spin it out.” Father turned to me smiling, then as quick as a cobra back to Mick and grabbed him by the throat pulling him over the table and whacking him on the side of the head with his open hand. Mick spun to the floor, mouth open, eyes ablaze and hand reaching for a bottle. Things looked on the verge of serious violence when a voice high on righteousness and indignation rang out, “George Dennis, have you no shame? Striking a boy just out of school, not old enough to vote, let alone see the ways of the Lord. Well, I think it’s time you and your Communist kind were hounded out of office and sent back to Russia. And as for you, young Michael, he could no more creep up a gaffer’s arse than an elephant’s, his bloody head is too big. Now get out the lot of you afore I call the police.”

Father stormed out first and we trailed after. This boat business was getting out of hand. As we stood on the terrace of the pub watching father stride away, the words came hissing out of Mike, “if he ever tries anything like that again, I’ll fucking have the bastard.” Try as I may I couldn’t think of any reply that would support him without betraying father. Then Alan said, “Did you see her when she lent over the bar? Did you? Her titties just about fell out, they did. You could see the brown bits. You know the ear holes? Fucking hell, I hope I dream about her tonight. Talk about hard-on.” I looked at Mick, we both looked at Alan, shook our heads and headed towards the working men’s club. I didn’t want to see father just yet.

I arrived home after a couple of subdued pints to find father and mother just getting over one of those rows, the subjects of which tend to rumble on for years between couples who have been married for nearly quarter of a century, in this case, booze, money and the union – mother hated the first, never had enough of the second and resented the third, father loved all three. For the next half hour mother berated the both of us with our shortcomings. These included my moral laxity in not defending father, his propensity for violence, Mike’s hypocrisy, him coming from a family that had scabbed during the 1926 general strike and the mortal folly of drinking in the afternoon. When a person like mother took the high moral ground it was wise to sit down, switch off and think of barmaids with big boobs, just hoping she’ll finish the tirade before the potato pie became too cold to eat (see Vol. 1 – “The Matriarchs in Mining Villages” for a different perspective of life when the bounds of their reason were overstepped).

About mother. My mother’s father had been killed in a mining accident in 1928. Kiveton pit after the defeat of the miners in 1926 was not a good place to work. The miners at Kiveton had been some of the most militant in Yorkshire. Now the bosses had the whip hand and they cracked that whip with increasing brutality. Conditions and pay had degenerated to almost pre-1914 standards. Mother’s family hand the story down that the undertaker had to put stones in the coffin to give the illusion of at least a little weight, there being so little of grandad to bury. The manner of his death was a scandal even for those dreadful times. The man in charge of igniting the explosives (the shotfirer) had set six separate sticks of gelignite, these he would fire in succession. This would bring the wall of rock down in a controlled manner instead of firing the charges simultaneously which would lead to unforeseen and chaotic results. The bloody man miscounted, he fired only five, then ordered grandfather forward to remove the fallen rubble. The poor man was standing over No. 6 shot when it exploded, he took the full force of the blast and was never seen again. All that was remaining could easily have been put into a small shopping basket without filling it. Not even his boots were recovered. The shotfirer was demoted and fined a week’s wages, grandmother was given £100 and a pension of 4 shillings a week for life, but only if she would accept that her husband’s death was due to his own fault. She had five daughters and two sons. The boys, just out of school, went into the mines. The girls, all except one, went into “service”. (this was a euphemism used to describe young girls working for low wages in the houses of the middle classes). All her life mother venerated the memory of her father and would become misty-eyed and tearful at the mention of his name. She was twelve years old when he was killed; she has many stories of the hard life.

Due to a surfeit of Sam Smith’s bitter, potato pie and a troubled mind I overslept next morning. When I arrived in the carpenter’s shop it was to find Alan staring into the fireplace. The blaze was huge and the heat intense. “What the fuck are you burning, Napalm? That’s ridiculous!” I was standing about twenty feet away and my overalls were beginning to steam. I could just hear Alan’s reply over the roaring of the flames. “It’s that cotton waste you used yesterday to soak up that spilled varnish and paraffin. I threw it on the embers, it warmed up, smoked a bit, then WHOOSH! Fucking great, hey?” “Fucking great? Fucking fantastic, that’s what!”

It was one of those occasions on which two people have the same idea at the same time and no words need to be spoken, all that’s wanted is time and certain trigger words to channel the thought process along similar avenues. In our case the words were Revenge and Blame – how to achieve our revenge and not take the blame. The conflagration subsided as quickly as it had begun, but it was gratifying to note that the wrought irons in front of the fire place still glowed a dull red after the fire had settled to it’s usual level. Our plans had to be set aside for the time being when the foreman arrived to give us our jobs for the day. I was to apply the umpteenth coat of varnish, Alan was to assist in assembling the steering gear. The mechanic working on the boat that day was to be George Marsh. His nickname (but not to his face) was Bog Breath.

That morning we ate our sandwiches and drank our tea and tried not to get too close to George’s halitosis, we would look at each other and smirk and use phrases which only the two of us would know the secret relevance. Finally old Bog Breath had suffered enough innuendo, turned towards us and shouted, “Are you two shagging each other?”

This would not have mattered too much had he not sprayed us with half chewed lumps of cheese and onion sandwich, mixed and softened with his usual strong black coffee. We quickly straightened our faces, washed our cups and went back to varnishing and tinkering. After work we sat in The Saxon together playing cards and planning how we could utilise this gift of wonderful destruction without being sent to prison for the rest of our teenage years and beyond. We thought of making electric devices which could ignite the varnish, we thought of clockwork devices, we thought of elaborate fuses. Fantasies evolved and disappeared but with each plan the risk outweighed the gain or proved impractical for our limited skills. As we sat, subdued and thoughtful, becoming more frustrated by the minute, in strode father. “Hello lads, I’m looking for volunteers to carry our “Beloved Union” banner in the carnival on Saturday. You three are perfect. You’re young and fit and you’ll be given free drinks in the beer tent at the end of the march.”

After the nastiness of the previous days Alan and Mick were none too keen to comply with father’s proposition, but like Paul’s vision on the road to Damascus it came to me – “THE CARNIVAL”. Every year the management, the church and the chapels put aside their rivalries and sponsored a carnival on the second Saturday in August. This coincided with the religious harvest festival and the return to work of the miners from their annual holidays. Also every year after this carnival day would follow carnival night, naturally. During the daylight hours of carnival most of the enjoyment was focused on the children, the fairground, the fancy dress parade, the games, fathers being pelted by soaking sponges, mothers hiding pieces of rock and broken glass in the sponges and all the things that make a carnival a carnival. But after twilight things would change. In the local church hall many of the famous rock bands of the sixties would raise the emotional temperature to boiling point. Freddy and The Dreamers would create the adolescent nightmare of unrequited love. The Seekers would be lost forever. In pubescent orgasms, as young girls threw their soaking underwear onto the stage, young men would seethe. Gene Vincent would slink onto the stage, clad in shiny black leather, and promise covertly with his index finger to stimulate places in the female anatomy that young Yorkshire miners had yet to discover. We seethed, being the rough-arsed rednecks that we were. Instead of burning down the church and church hall, stuffing Gene Vincent’s digit up his own arse and giving The Dreamers and The Searchers a nightmare to remember, we would turn inward and fight each other. The cops loved it. After we had finished kicking the shit out of each other, they would arrive and carry on kicking the shit out of us. What a wonderful decay.

We made the molotov cocktail using a wide-neck milk bottle so that the petrol would splash even if the bottle didn’t break. Before the end of the shift on Friday I collected all the varnish-soaked wasted cloth and spread it at the side of the boat. All we needed was Saturday night and luck. The decision as to who should do the job was easy. I was the hardest drinker and the fastest runner and, shit, it was my idea anyway.

During the carnival and on the march through the streets we met the bastards who had given us the hard times with the boat. The Enginewright and his assistant shouted to us as we carried the banner, “Nearest you three have been to work in months. Nice work lads. At least you can follow the band.” We smiled. We took part in the games that children of all ages enjoy – drinking, eating, hitting, throwing balls, laughing at others and being laughed at. After a while we forgot our secret agenda and became part of the carnival.

The British are renowned throughout Europe for their inability to deal with alcohol and rightly so. Adults are regarded as children. When buying booze and drinking in public, the times would be strictly enforced. Between 11 ‘o’ clock in the morning and 3 ‘o’ clock in the afternoon you could buy a drink in a pub (then you must rest). Between 6’o’clock in the evening and 10.30 you could buy a drink in a pub (then you must rest). Thank you Mother State but no thanks. Treat people like children and they behave like children. So it was with us. By 2.30 in the afternoon the consumption of beer had become ferocious. The young girls of our milieu had become emboldened by Babycham and barley wine (a most potent brew devised by a witch and warlock in Norfolk), we young men rowdy and bilious on black puddings, pork pies and warm ale.

The entertainment for the rest of the day was set. As we lounged in the sun, searching for dregs to drink or underwear in which to wander, we became restless at the futility of it all and made our ways home to wash and dress for the evening enchantment.

The off-licence is a peculiar place. It can sell all manner of goods but could only sell booze at the times mentioned above. Thankfully, the owners of these places were, and still are, greedy, unscrupulous and totally understanding of the teenage predicament. Therefore, before going into a gig or concert we would fortify ourselves before entering the totally teetotal church hall or equally benign establishment. In those days, under such circumstances, I would drink two or three bottles of Guinness and buy half a bottle of rum to mix with the coke to be bought inside. Alan would buy brandy to give to the girls who had smuggled in Babycham (brandy and Babycham – another potent mixture from Norfolk), Mick would smuggle Bacardi in, drink two-thirds of the bottle, then re-fill it with water and pass it round with largesse (nobody ever suspected him) and so the night progressed.

If I remember correctly the group that headed the bill that night was Wayne Fontana and The My Members, a bunch of fortunate 23 year olds posing as teenagers. Wayne Fontana looked old beyond his years even then, lucky bastard. As I watched I became him, as I picked up the pheromones my mind began to wander again – this was not the plan – WHAT PLAN?

Glad to relate that as the night wore on I became drunker by the minute. The rest of the story was given to me the next day. It would seem that the three of us had agreed to separate and then meet up at the bridge on Hard Lane. We then met at least five people walking back to the next village (Harthill) and had drunken conversations. We then strolled through the pit yard, picked up our molotovs, lit them, threw them through the carpenter’s window and wandered as pissed as rats to the end of Pit Lane. By the time the fire alarm was raised we were sat across from the tobacconist’s wondering what the fuck all these people could be dashing about at. The next day after the admonishments of mother about drinking till early on a Sunday we met at The Saxon. The first pint is the most important after a night when you can’t remember how you arrived home or found your bed. After the first sips I asked Alan, “How did it go?” He answered, “Great! Don’t you just love the smell of Sunday dinners cooking?” I said, “Who’s got the blame?” He said, “Some bunch of drunken revellers from Harthill. Seems they threw half a bottle of whisky through the joiner’s shop window and it caused a flashback from that great fireplace that’s always smouldering in there. My comment according to Alan and Mick was, “Fucking waste of good whisky.”

A continuation of the chronology: late 60s to early 70s

…1969 wildcats…In Place Of Strife…1970 wildcats…

In October 1970, a national NUM ballot achieved a majority (55%) in favour of a strike, which was less than the necessary ⅔ majority. Wildcats broke out. At one point some 103,000 miners from 116 pits were on strike. The NCB upped its offer. The C.P. was losing control of the strike it had hitherto been able to organise – other State capitalist organisations were attacking the CP in order to further their own bureaucratic aims. The chairman of the NCB denounced ‘hooliganism’ and a section of the bureaucracy tried to vigorously recuperate the strikes through half-feigned opposition to the NUM old guard, with the aim of reforming the union. The Stalinist McGahey urged miners to try to change the bit in the union rule about a ⅔ majority being necessary before the union could officialise a strike. Leftists opposed a further ballot and called for a special delegate conference, a very well-tried method for British unions to try to recuperate base action by means of emphasising the democratic nature of trade unionism – low-level bureaucrats being allowed a voice, unions being able to be influenced in their recommendations by base action. The left of the bureaucracy was gaining ground – through a rank and file trade unionism which had a critique of sell-outs and with the aim of democratising the union, along with having a “more representative” stratum of middle-level bureaucrats. It was a reform that balanced the conservative function of trade unions with the desire and confidence developing amongst miners – it was more a genuine representation of the contradictions of the mining community than the way the old style-Stalinists and the right wing of the Union had controlled things in the union since World War II. So the main result of the strike was a compromised change of the rule-book to making a strike official if it got 55% of the vote.

A text by Dave Douglass and the Webbs criticising some aspects of the miners’ unions’ history

The following passage is taken from a pamphlet entitled “Pit life in Co’ Durham: Rank and File Movements and Workers Control.” (A History Workshop Pamphlet).

The miners unions were the first trade unions in the country to develop a section of full time officials. When the Durham Miners Association was founded in 1869, the county was divided into three districts and an agent appointed to each of them. Their weekly wage was to be £1-5s-6d. Their number increased as the union prospered. It was the same in other coalfields.But at the same time as relying on full time representatives, more than other working men at the time, miners also distrusted them deeply. Their very distance at area office was a sufficient cause for mistrust, and their actions plagued the miner with annoyance. In all the disputes within the DMA there is a recurring pattern, a basic fear of being misrepresented which can be seen in the type of motion put forward at the DMA calling for mandates, card votes, records of who voted, which way etc., and also in the general suspicion of the conciliation machinery which the DMA worked so hard to set up.The full-time officials soon developed a particular character. Almost invariably they were drawn from the ranks of the moderate, self-educated, temperate miners. Once elected, they thought their role was to inflict upon the members their own moderation and lead rather than serve. As early as 1870 they ruled that ‘any colliery which struck in an unconstitutional manner should be denied union aid’. The members found that they were being policed by the men to whom they were paying wages. The officials became more and more preoccupied with arbitration and conciliation as the cure for all ills, and more and more impatient of local action which ran up against it. The leadership rejoiced in the formality of the conciliation machinery; they exalted the authority of the Joint Committee even when it was used against its own members, preferring any course of action, ‘even simple submission’, in preference to a strike.From this point on the struggle in the coalfield became three sided. There were the men, the owners and firmly between them the full time agents, who negotiated on their behalf but came to totally unsatisfactory agreements and then spent the bulk of their time trying to ram them down the threats of the men. To make matters more complicated and more infuriating to the lodge with a strong grievance – there was a joint Committee of the DMA and the coal owners, a high court which sat in judgment on them, and whose rules were supposed to be binding.The lodges hated the idea of leaving negotiations in the hands of full time officials. The constant appeals to abandon the joint boards with the coalowners, the suspicion of the Sliding Scale, the mistrust of the proceedings in the DMA executive itself, as well as disputes between the individual lodges and the miners agents, were all based on a deep-felt resentment of delegated responsibility, whatever form it took.The miners traditional mistrust of ‘delegated representation’ is a carry on from his traditionalself-reliance and independence at work. He dislikes the idea of anybody deciding what he should do, apart from his ‘marras’ and himself. It is at best something which has to be put up with. His wages and toil to get them are a big thing to trust in another man’s hands. He prefers the open direct representation of ‘we are all leaders’. Even in the case of a working miner who is a branch official, yes – they can see he is a worker, but that would be no call to get excited, they still would only trust him if he was seen to be acting on their behalf and the results were coming in. When the lodge secretary goes to see the gaffer a deputation of marras will often go with him to see that he really does represent them. At branch level the union committee is of course elected by the rank and file, subject to dismissal, and up for re-election every two years, but even these men have to be watched. The branch committee man, if he is a good one, even the agitator, can be got at many ways by a gaffer: he may be offered a pleasanter place, away from the centres of trouble, if he will only show himself to be ‘reasonable’.The attitude of the rank and file towards the lodge committee has always been – if the branch officers are not negotiating the right terms kick them out, or build an unofficial committee to take their place. It is the rank and file themselves who take the initiative in all events. On many occasions strikes start in a wildcat way long before a branch meeting can even be held. Men walk out of the pit on strike as soon as there is something they won’t put up with. A group of marras, or a shift, will go to see the manager on their own, and often have refused to take an official of the branch with them. If the branch official is brought in it is sometimes only as a formality. They prefer to speak for themselves. Rarely, if ever (and never in my own experience) do the workers carry out the rule of working under protest