The CGT – sheepdogs in wolves’ clothing

Preliminary notes on the new labour laws and the current, recent and history of class struggle in France

Published 8/10/17

The CGT pretends to be a threat to the government, but this is just a disguise in order to maintain their rôle of shepherding the flocks of its supporters all the better to have them fleeced. Far more than probably anywhere else in the world (other than dictatorships, or semi-dictatorships) the unions in France are very much an intrinsic part of the state and work as a central part of the management of capital. The union question is probably the most central question facing any would-be social movement in France that doesn’t want to end up repeating old mistakes and being inevitably defeated.

The CGT pretends to be a threat to the government, but this is just a disguise in order to maintain their rôle of shepherding the flocks of its supporters all the better to have them fleeced. Far more than probably anywhere else in the world (other than dictatorships, or semi-dictatorships) the unions in France are very much an intrinsic part of the state and work as a central part of the management of capital. The union question is probably the most central question facing any would-be social movement in France that doesn’t want to end up repeating old mistakes and being inevitably defeated.

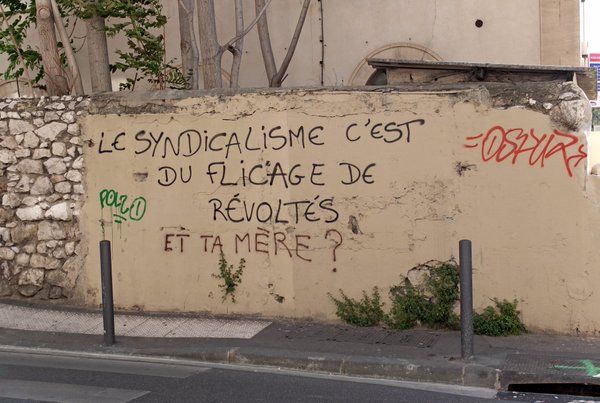

“Trade Unionism is the heavy policing of revolt”

“As long as individuals express the need to be represented, they are always confronted by the fact that the representation that they have chosen escapes their control.”

– Andre Drean (here)

Up until fairly recently, recognition of and critiquing the class-collaborationist function of unions – particularly the CGT – was taken as a given amongst radical currents in France. But here, as elsewhere, the counter-revolutionary crushing of memory has had a depressingly debilitating effect. In 2006, shortly after the movement against the CPE, anarchists and the CGT had a serious physical fight in Perpignan on the Mayday demo. Obviously everyone associated with the “anarchist” or “anti-authoritarian” milieu supported the anarchists in this fight. Nowadays, we’d probably find some so-called anarchists siding with the CGT, if today’s befuddled mentality is anything to go by. Because the current movement against Macron’s new reforms of the « Code du Travail » [« work Code »] in France has been shrouded in a fog of confusion. Almost all the various « anarchist » or « anti-authoritarian » organisations seem to have accepted the CGT’s (or Sud’s – see Appendix) version of the law, and copied and pasted it onto their various bits of propaganda. Some « anarchists » even temporarily accept being part of the CGT’s « service d’ordre » (demonstration stewards). In recent leaflets the CGA1 (a split from the Federation Anarchiste), even stands for the defence of the CGT’s bodies of negotiations with the State. It seems that many so-called libertarians, submissive to the repulsive politics of the CGT and the defence of their managerial position within French companies, believe the promotion of their organisation and its image is more important than contributing to the class struggle. They are incapable of distinguishing between enlarging the profile of their organisation through populist acquiescence towards the CGT racket on the one hand, and contributing towards a subversion of this law, of bourgeois laws in general and of the exhausting society of wage slavery they are aimed at reinforcing, on the other. Lacking all critical distance, publicising their organisation takes priority over any basic sense of class anger towards class collaborators such as the CGT. And outside these organisations, there’s an almost unprecedented confusion about the CGT and the new laws, both deliberately manipulated and unconscious, permeating the minds of rebels and would-be rebels.

In fact, Macron’s new labour laws are far more subtle with its divide & rule and vague in how it expresses this than most of the unvaried interpretations of it – for example, those aspects concerning redundancy payments. For some proletarians it’s partly an improvement in conditions: in the event of dismissal for economic reasons, workers get 25% more. This is valid for all employees in general, regardless of the size of the company. [note 22/10/17: apparently this was slightly modified a few weeks back – see note in comments box below].

On the other hand, with Macron’s new decrees, in order to lay off wage slaves legally, for managers the conditions have been made easier. Now, even in large companies operating globally, assessors and labor inspectors only need to take into account the “health” of the part of the company established in France, rather than how this company is doing internationally, which previously was the case. However, when it’s a case of unfair dismissal, without legal cause, redundancy payments are now more limited than previously (except in cases of discrimination, sexual or otherwise, repression because of trade union activity, etc. where the old very favorable system still remains). In France today, unfair dismissals happen mainly in small and medium-sized companies, roughly fewer than 50 employees – so it’s obviously the bosses of these smaller-sized companies who stand to gain most from these “decrees”. Of course the definition of « legal cause » and « unfair dismissal» might well change, especially if the present salami tactics3 work for the ruling class, and then this may later be applied to the larger companies, but for the moment this is not the case at all.

However, the law tentatively proposes, over time and depending on various degrees of consent, a withdrawal of previously granted « work security », making it potentially easier for the boss to fire workers, etc. But it’s not an immediate rapid charge towards the conditions of neoliberalism present in most other countries, despite the crude simplifications presented by the CGT. In fact, aspects of it give privileges to union officials. They are being allowed more time off for studying – e.g. 20 hours per week to become a Work Inspector, or 2 months training for work-related studies. And they’re being given an extra hour off per week to attend union meetings. It’s a clever divide and rule that the unions – and particularly the CGT – are only complaining about because they could eventually lose members and money and privileges in their vital role as part of the management of capital. It’s a form of gradual salami tactics, almost designed to promote the muddled mess that is everywhere reciprocated in the ideologies of the false opposition. I certainly don’t pretend to understand every aspect of these new proposals : they’re not easy to read, as they’re written for political-legal specialists in a language only they can understand (« Politicalegalese »)3, for which France’s bureaucracy holds the World Title. In fact, all its tentative suggestions in these « ordonnances »4 are probably intended as a way of testing the water, checking out how the « opposition » to it pans out in order to feel their way around the choices of going in hard or of taking a softly-softly approach.

The fear of complexity and the apparent sense of “community” and sense of certainty derived from simplisticly “taking sides” rather than making sides, makes people easy fodder for Leftist demagoguery. Whilst this law is not clear, it is clear that the falsifications of it by the unions, with the Left and the anarcho-Left hanging onto their coat-tails, can only help towards leading to defeat. As usual. Their manipulative dishonesty invariably (eventually) leads to demoralisation on the part of anyone who seriously wants to stop this slow advance, this progress of increasingly repressive miseries whose effects are increasingly stifling and crazy. And no-one is immune to these demoralisations, including obviously many naive people in some of these organisations.

**************

The main problem about this « movement » (which so far seems to be moving in the wrong direction) is a defence of the unions’ function as if it was a defence of hard-won workers’ struggles. Given this it seems vital to examine some of the history of the unions’ constantly increased integration into the development of capital in France.

Some aspects of the history of the CGT from 1909 to the present

In 1909, the French state responded to the intensification of strikes – particularly by the CGT (which, at that time, included a lot of anarchist workers, and was considered semi-anarchist) – by offering them pensions on retirement. This was rejected outright as an attempt to pacify their combatitivity, as well as being a con since it would simply mean less real income resulting from greater taxes or national insurance from which the pensions would be paid. In any case, the retirement age was fixed by the State at 65 years, whilst life expectancy for waged workers was 55 years on average. The anarcho-syndicalists called it “the pension for the dead”! (similarly, in the 1970s, when workers called their retirement “the widow’s pension”, since they had a life expectancy of 67 years!). This pre-WW1 CGT had tensions between radicals (mostly anarchists) and reformist currents. The latter agreed to have legalized demos in 1909 (with demonstration stewards to prevent it from getting disorderly). Later, the CGT agreed to declare their demos to the state beforehand. So, little by little, a legal framework for strikes and demos was adopted and modified with variations in capitalist cycles and developments, within general labour laws, etc. As a reward for this pacification, the French state, in the run-up to WWl, gave the unions a privilege probably unknown in any other country in the world, either before or since: the permission to hold secret accounts not subject to tax, state surveillance or regulation!!! This unbelievable truth, stranger than fiction, still holds true today.

Probably this was one of the factors behind the majority of the CGT, which held a semi-anarchist ideology at the time, in supporting the state in the first world imperialist massacre5. In 1915, in order to further integrate the unions into the mass slaughter of proletarians they claimed to represent, local « Workshop Committees » (« Comités d’Ateliers ») were formed in factories in which union reps, including « trenchist » anarchists who supported the war, were involved in limited decisions at a local level. This was the response of Thomas, a leading light in the Socialist Party, who was the Minister of Munitions6, to strikes that were developing in certain industries during the war. The state at the same time transformed the mutual aid funds of the unions (« Caisses de solidarité ») – which workers had run themselves – into state-run unemployment benefits. These were, as they are now, funded by taking a part of workers’ wages in the form of tax etc. – the beginnings of the welfare state in France, the state recuperation of self-organised forms of solidarity (see « the welfare state isn’t now, and never was, a “genuine gain for the working class” » ).

By 1936, the CGT having become the union section of the utterly Stalinist French Communist Party, directly negotiated with the state to get people back to work during the massive strikes of the popular front.

As for the « Comités d’Ateliers » (« workshop committees ») begun in the first world imperialist war, they were the local precursors of what in 1945, following the end of the second world imperialist war, became the «Comités d’Entreprise» (« enterprise committees »), which covered, and still cover, companies nationally, with unions participating in day-to-day management decisions. Following World War II, this was part of the deal between de Gaulle and the French Communist Party, who won more votes than any other party in the 1945 election ( it was also due to the fact that they took part in the Liberation – or at least this is what they claimed, since their rôle was very ambiguous until ‘44 at least). From 1945 onwards, at least 60 % of unions’ finances came directly from the state, the rest coming from members’ dues (the latter being the economic base for competition for recruitment between different unions)7. And later on – in the ‘50s – about 80 %. of their finances came from the state. Since 1958 unions have been allowed to be elected to « Conseils d’Administration » (administrative councils responsible for the enterprise’s overall policy decisions, not just the day-to-day ones) in state enterprises, occupying up to one third of the board’s membership. Union participation in these boards also applies to industries that have been de-nationalised, such as Orange, previously called France Telecom. All this means, for example, that the CGT section of the EDF are directly involved in the policy decisions of the nuclear power industry, including the military section of nuclear power ! As I said, truth is stranger than fiction!

We should also mention this : a large part of the French anarchist movement decided after 1945 to enter the main unions with the fantasy of radicalising them (instead of participating in the new anarcho-syndicalist CNT, which they left, or trying to establish autonomous contacts, groups, etc.), while the CGT was close to the USSR, and Force Ouvriere (FO – a breakaway from the CGT, created soon after) was State and CIA-funded. This entrist strategy, of course, never worked (as Unions’ collaboration with the State deepened year after year and anarchist influence decreased) : anarchists in fact soon adopted a trade unionist ideology, accepted having delegates, and so on. Maurice Joyeux and Georges Fontenis, leaders of the FA (Anarchist Federation), became famous for their opportunism and bureaucratic logic.

After the explosive return of the social question in 19688, workers were given massive pay rises in order to get them back to the misery of the factories, and other hell-holes, a pay rise that was eaten up about a year later with inflation. But the compromise needed to pacify a majority of workers – the Grenelle Accords – meant, amongst other things, that union stewards/reps did not (and still don’t) even need to be elected by those they’re meant to represent. Just one individual in a company, with no previous union membership, can become a secret rep if the union approves of it. S/he is then permitted to display union texts on a notice board at the entrance of a company, and then a week later, allowed to distribute them. More importantly, such a « phantom » rep has a protected salary and cannot be made redundant without an inquiry including a Works Inspector (i.e. the state). Meanwhile, they participate in the Works Committees, Health & Safety committees and Holiday Bonus committees, and participate in the management of redundancies, without any of their fellow workers necessarily knowing who s/he is.

Despite the whining victim propaganda of the CGT, claiming their imminent destruction because of the new Labour Laws, the government has no desire to destroy the unions, any of them – as they provide the safety valve of a false opposition very useful for disarming genuine opposition (e.g. de Gaulle, in his Memoirs, thanked the Communist Party, to which the CGT was aligned, for suppressing insurrectionary tendencies both in 19459 at the time of the « Liberation » and, more famously, in 1968).

The CGT’s main problem with the Hollande government was that they hadn’t been involved sufficiently in any consultations in the run-up to the bill proposing the Labour Laws of 2016, which was the pretext for claiming their very existence was at stake. The pretense was that insufficient consultations meant the end of the union. A falsification which was accepted at face value by the vast majority of anarchists and « anti-authoritarians » during this movement.

It’s vital to know that probably less than 8% of workers are in unions – about 4% less than in 1968 . Of course, this is partly due to the huge increase in unemployment, part-time jobs and auto-entrepreneur status since that period. However, like in ‘68, that doesn’t mean they don’t have a significant detrimental influence on struggles. Particularly the CGT, which was increasingly linked to the French Communist Party since its formation in 1920, although officially it broke this link in the 1990s.

The CGT’s strategies of demobilisation have created a tradition of controlled-action (as opposed to direct action): it has become much more difficult for proletarians to affirm a will to struggle through direct action, since legal action and vertical action has replaced autonomous forms of struggle for a long time in the CGT. The CGT can assume and organize a certain level of « violence » if pressure from the base is strong. For these reasons, critiques of the organization among the rank and file are pretty uncommon. It should also be remembered that the low levels of affiliation nowadays means a lot of affiliates are militants (meaning they’re active in the bureaucratic-legal stuff).

Here’s just one recent example of this show of violence within the complex interaction between the unions and the state: in May 2017, shortly after Macron’s election, CGT members at a factory manufacturing car parts (Bosch), which was being threatened with closure due to lack of orders, threatened to blow the factory up with gas canisters. The CGT has often made such threats before, but they have never been carried out. Shortly afterwards Macron demanded that Peugeot, Citroen and Renault stop buying so much from cheaper overseas markets and increase their orders from this plant by 20%. At the same time he provided the companies with money from the state needed to make up their loss. This illustrates that France is very far from any crudely classical neoliberal project (as exemplified by the US and the UK, for example), even if it’s slowly heading in that direction. But more significantly, this event shows not simplisticly the power of the unions but of the necessity of the state to have the unions preserve their image as genuine protectors of workers within the confines of their miserable rôle within the capitalist production process. After the apparent defeat of the movement against the new Labour Laws, the state needed the CGT to reassert its image of a genuinely useful opposition for the next round of intensification of workers’ exploitation in the form of new labour laws, in order to maintain workers’ faith in and compliance with the CGT leadership (I say “apparent defeat” because in fact, it was partly a victory – many of the worse aspects of the law were withdrawn before the summer, though probably this was more to do with the violence of the movement outside of union or leftist control).

The CGT during the movement against El Khomri’s Labour Laws of 2016

Let’s look a bit more at what happened vis-a-vis the unions during the movement against the Labour Laws in 2016.

Before that, we should firstly remember that, back at the beginning of October 2015, over 5 months before the movement against the Labour Laws, Air France workers, independent of any union instructions, chased managers who were implementing redundancies and tore the shirts off them, and 2 security guards protecting these managers were knocked out.

role-reversal at Air France – now it’s the workers who have the shirts off the backs of the managers

role-reversal at Air France – now it’s the workers who have the shirts off the backs of the managers

What was the unions’ response? They quickly dissociated themselves from the workers’ anger : « Air France CGT has expressed its willingness to “calm things down” after the excesses in CCE. “We did not want CCE to be invaded,” Mehdi Kemoune, deputy general secretary of the union told AFP [some media organisation]. He claimed to have intervened to protect HRD Xavier Broseta, target of the protesters, which led him also to be jostled. According to him, the CGT had “warned” the directors that the situation could escalate, calling them to strengthen security. » The union has to be shown to be able to police its members, or at least be willing to, otherwise it has no function as the pimp negotiating the rate at which the wage slaves get screwed – no legitimate function within the system.

Just two weeks before the movement started at the beginning of March, on February 23rd an inter-union meeting, including the CGT, made a declaration which in no way called for the abandonment of the proposed Labour Law bill but only a few minor modifications. Not surprisingly, in 2015, the trade unions had participated in the “Combrexelle report”, a government document that incorporated the recommendations of MEDEF in its “emergency plan for employment” to serve as a basis for this Labor Law. It took an agitation on the Internet (petition and mobilization on and by social networks) at the beginning of March for the CGT, FO and SUD to stop publicly assuming the reactionary positions they had held just days before. But in this epoch, the incessant falsification of history and an almost pathological reduction of individuals to pure immediacy, means more and more people have a memory no better than that of a goldfish. Hence, despite all previous examples to the contrary, the CGT could present themselves in 2016, as they do today – as valiant combatants who had always been valiant combatants.

On March 9th France: between ¼ and ½ million demonstrated against the new labour laws. The unions nationally refused to call a strike – only local unions were involved (not that they’re that much better). On this day there were demonstrations throughout the country and at least 6 towns10 had significant confrontations with the state, whilst students at 100 high schools became involved in this movement .

On 17th March “…dozens of young radicals and casseurs disrupted the Parisian procession …Ten minutes after the start of the parade in the charged atmosphere, some were throwing projectiles, cans and other bottles at the riot police. The atmosphere is “definitely less goody goody than last week,” said a CGT unionist come as an observer.” It was at this demo that the CGT demonstration stewards started handing over « troublemakers » to the cops (I put « toublemakers » in inverted commas because it’s obvious that capitalism troubles the vast majority and making trouble against it is one of the best ways to feel less troubled).

Which is why on March 24th in Paris the CGT HQ had its windows broken given their previous collaboration.

However, also on March 24th, the local CGT, expressing sections of its rank and file trying to push for a genuine opposition from the leadership to the Labour Laws, brought Rouen to a virtual standstill, as port and shipping agents went on strike and blocked roads, whilst in Le Havre striking dockers blocked the outskirts of the town. Later on, at the beginning of April, these dockers warned that they would block the whole city if students or high-school students in Le Havre were to be imprisoned following the demonstrations. I have no idea if this was a threat they continued carrying out during the rest of the movement.

In fact, several local CGT unions went on strike during this movement. For instance, on the 26th April, in Paris, precarious workers, occupied the world-famous Comedie Francaise theatre, forcing the cancellation of the show. 10 national theatres were occupied (or parts of them were) during this movement – mainly by casualised cultural workers ( “intermittents”) , which included both local CGT and non-unionised workers (see this for a text on their movement in 2003).

Nevertheless, these occupations, if the one in Montpellier was anything to go by, remained very conservative « occupations », essentially symbolic.

The following is what I wrote about the occupation there on 12th April:

France, Montpellier: casualised cultural workers occupy theatre

in theatrical costume:

“We’re all in danger” “Angry cultural workers”

It has to be said that these nude photo-shots, in very cold weather, are purely for the cameras, quickly carried out, then back on with the clothes. They’re standard “intermittents” practice and are never carried out in crowds, because that would be exhibitionism and therefore – heaven forbid! – illegal! So these intermittents confine themselves to one hall, and don’t want to break into the shower room area, because there’s lots of stuff there that could be damaged maybe. And that might upset management. Since most of this theatre is not being used at the moment, this really is merely a show, particularly as the most immediately obvious problem with this action was that it’s taking place far from everywhere: an area in which only buildings associated with culture exist, no shops or residential buildings or any non-cultural workplaces. Those who take their work far too seriously find themselves defined by it totally even when they think they’re struggling; hence these performers can only perform , whether paid for it or not (of course, a lot of them aren’t paid performers; they work the ropes or do the electrics or whatever in theatres, concerts, etc.). But although this occupation is rather miserable it’s all for the cause, even if their cause – as long as it’s carried out in this timid fashion – is doomed to failure.

In fact, a great deal of CGT actions are merely symbolic – like on June 3rd 2016 when in Bayonne a station was symbolically “occupied” by train drivers and others for about 10 hours without any significant disruption

Bayonne station, 3rd June 2016: CGT organises the symbolic die-in of trade unionism, which – sadly – is alive enough to kill off genuine struggle amongst those hoping for some salvation through bureaucracy dressed up as street theatre

***

The composition of the wage-earning workforce in France has been polarized for several decades now; between, on the one hand, qualified and relatively secure workers (part of them working for the public sector) and, on the other hand, low-skilled, or temporary workers. For the most part, the way in which trade unions have been organized has always prevented communication between these two different “sections”, whose consequences have been, as the trade unions admit, the generalization of precariousness outside of the more protected sectors, as an inevitable counterpart to the rights acquired by these more secure skilled workers. The unions strongly oppose any communication between the more obviously integrated, and usually older, workers and younger proletarians, unemployed or in precarious work, and those destined to become so. Hence their blatant hostility towards the most radical elements during the struggle – those who smashed things up, particularly the high school students. To give just one example from direct experience, on April 14th in Montpellier, the CGT, along with other unions (e.g. Sud) abandoned the demonstration before it had even begun because the high school students had behaved naughtily beforehand (see the entry for 14/4/16 here) and they didn’t want to be associated with them. A couple of CGT stewards remained merely to observe, and at one point one tried to stop the demo spreading from the tramway all across the road, a futile attempt as he was utterly ignored.

The CGT, as demonstration stewards, are there to protect the nice image of a hierarchically-controlled demonstration. They have certainly never protected any demonstrator against police violence, but have acted like the cops themselves. On Mayday 2016 they complained about the insufficient numbers of cops. In Nantes, the CGT prevented the tractors of the peasants of the ZAD of Notre-Dame-des-Landes from entering the demonstration under the utterly false argument that “the ZAD has nothing to do with the object of this demonstration “. In Marseilles, on 12 May, the CGT stewards assaulted with sticks and teargas loads of different demonstrators in order to disperse them. And during the demonstration on 17th May in Paris they charged the protesters who were slow to disperse. Similar abuses have been reported in several other cities. The police left the union demonstrations of impotence alone whilst systematically attacking the uncontrolled “wildcat” demos, sometimes acting in collaboration with the CGT.

Caen, 17th June 2016: demonstrator beaten by CGT stewards

Caen, 17th June 2016: demonstrator beaten by CGT stewards

However, cops are not always aware of the necessary politics of keeping the CGT happy. On June 14th, in Paris the demonstration gathered together probably half a million people (80,000 according to the police, 1,200,000 according to the organizers). The whole of the route was fenced off by barriers several meters high, which made any escape impossible – and also any way of getting into it: thousands of demonstrators who wanted to join the procession en route were actually blocked by this fencing. The police were extremely heavy about enforcing this division. At the end of the demonstration, a large group of CGT dockers confronted the CRS after one of their own was seriously wounded by a cop grenade. That evening, the prefect of police in Paris declared how scandalized he was by the presence of CGT flags in the area of confrontation: “There was a form of solidarity, at least passive, with the casseurs”, he said, denouncing the fact that some CGT trade unionists tried to hamper the interventions of the police, including arrests. Valls, the PM, accused the CGT of having had an “ambiguous attitude towards the casseurs” and Hollande threatened to prohibit any demonstration which couldn’t assure conditions of security, demanding that the CGT re-take the lead in the parades and to police them once more against the “unorganized”. The absolute priority for the government was to break the virtually unique moment of solidarity, and its potential development, that occurred during this demo.

On June 21st the PM, Valls, banned a planned demo in the centre of Paris by the unions. The next day, the State rescinded this threat by offering a strictly controlled half-mile route around a canal as a sop to the CGT bureaucrats…who then hailed it as a “victory for democracy”. Because it had allowed them to save face whilst joining with the government with the need both had to put an end to acts of vandalism. The secretary-general of the CGT Philippe Martinez had already justified the prohibition of participation in demonstrations sent the day before the demo of 14th June to 130 people (including some CGT members) : “It’s normal – they are thugs” he said, judging them on the basis of the police files and not even on any judicial proceedings.

For the CGT leadership, all confrontation with the police is thuggery. Which is why they, despite the brutality of the cops in attacking the blockades of Esso at Fos-sur-mer, issued instructions not to resist. There were several blockades of refineries, but most were short-lived and hardly effected distribution of petrol (the shortages lasted 24 hours). Perhaps the only exception was in Le Havre which remained blocked by the strike for several weeks, to the point of compromising the supply of Paris and its airports. Nationally, there was limited access to petrol for only one day. If 2010 is anything to go by, it’s fairly probable that this blockade was more of a show than a reality. There was a blockade in Marseilles of the commercial center Les Terrasses du Port, built on port sites, on 26 May by the Intersyndicale, and a blockade of the train advertising the Eurofoot 2016 in Paris Montparnasse station by the railwaymen of SUD-Rail on June 8th. These blockades lasted only a few hours, given the rapid intervention of the police and the CGT ideology that confrontation = thuggery. But the blockades hardly effected daily life for the vast majority: the shopping centers continued being supplied and very little of the economy was disrupted, even less than in 2010. It is clear that the trade unions did not want to effectively block the country, but only to use the blockades as a means of pressure to force the government to open negotiations.

**********************

Let’s sum up:

Despite all their endless cries of “this is an historic attack against our rights! A century of struggle thrown in the bin!!”, the CGT nationally confined themselves to 24-hour strikes which were often not followed by their members. They never attempted any unity of action between trades, professions, and places of production. “Interprofessional general assemblies” were sometimes held, but only the union representatives were invited. They certainly never called a general strike, never contributed towards breaking down separations between different sectors of the employed working class, despite the beatings, the hospitalising of hundreds and the obvious fact that this law would worsen the conditions of proletarians throughout the country.

It’s not enough for the rank and file to simply make initiatives whilst keeping quiet about the CGT’s complicity (collaboration with the cops and, before the movement began, their collaboration with the bosses, their general fear of anything outside their hierarchical contol, etc.). Individual CGT members may privately feel a great deal of disquiet about their leadership but if they don’t somehow make this public (even if it may involve being clandestine about their critiques, for fear of being heavily disciplined) there will never be a break with standard union manipulations. This is the contradiction every member of such traditional organisations as unions feels : either they make some kind of break with it by asserting their secret critiques and genuine needs, or they resign themselves to the apparent security of remaining a member of an organisation that claims, like protection rackets everywhere, to protect them, and then fall victim to a defeat in which they failed to assert themselves, hiding the shame of this failure by claiming it was the leadership that failed them. Those who want to be lead rather than take their own initiatives will always claim to have been sold out. Ultra-leftists may blame the union, but really the union behaves like unions invariably behave : it’s innate to unions that they assume a social function which escapes the control of each union worker and the ensemble of union workers; a social function necessitated by their position within the very logic of commodity production and consumption. So, the essential blame comes from the failure of those lowest in the hierarchy to challenge and test out the manipulations of those higher up. Workers too often feel they need to remain members of a union to flee from the anxiety-ridden need to find themselves and each other in struggle without and against the hierarchy.

It’s essential to have a clear understanding of the duplicitous rôle the CGT especially play during these movements as well as other aspects of them. The delusion that the heroes of the CGT are somehow a genuine opposition and in genuine danger of being destroyed illustrates yet again how the counter-revolution permeates and confuses the consciousness of those who claim to want to contribute to a revolutionary movement. Movementist ideology is so willing to succumb to some easy populism, and wishful-thinking, that probably a majority of anarchists and anti-authoritarians seem to consider a basic critique of the unions, and in particular of the CGT, is somehow out-of-date. Which merely shows how the CGT has changed its image, how the CGT is able to present itself as the primary victim of the Labour Laws and as the vanguard of the struggle.

****************************************************************************

It should be made clear that the recent demos (12th September11 and 21st September) involved people who, for the most part, were not directly implicated in the recent changes to the « work code » : the worst effected are mostly those in private and relatively small companies, few of whom took part. However, most of the union members who participated in the demos either worked for large companies or for the state. And the others who took part were either the Leftist or anarcho-leftist organisations, not many of whom are immediately implicated in these reforms, or relatively marginal proletarians who are either officially unemployed or students. However, the most significant struggles ahead in France will probably be amongst the public sector workers – particularly over pensions which Macron is hoping to cut back. Watch this space.

Appendix on SUD

This text concentrates on the CGT, but Sud is also as criticisable as the CGT. This union, generally speaking, is more able than the CGT to accept within it leftists, ultra-leftists and also potentially rebellious but indecisive individuals. See, for example, SUD-Rail, SUD-Education, etc. This comes from the role that the CFDT played after May 68 and then from the role of the CFDT-Opposition fraction, from which Sud was born. Typical example: the duplicity of SUD on its involvement in the nuclear power industry. The CGT has long been pro-nuclear, but Sud officially talks about a slow withdrawal from civilian nuclear power, whilst saying nothing about military nuclear power uses; it talks about alternative energy, and so on, but, like the CGT, presents candidates for the board of directors of the Atomic Energy Commission (CEA). See this about the development of Sud during the strikes of 1996:

« The frequent references by the founders of the SUD to the origins of revolutionary syndicalism, indeed of anarcho-syndicalism for those who are also members of the CNT, to the original trade unions and to the first associations which had as their objective the emancipation of the workers, can develop illusions. Likewise their hostility to the most narrow-minded corporatism.

But their steps were more the result of the exclusion imposed by the leadership of the CFDT than of any critical reflection. In reality, they are participating in the renewal of trade unionism, a renewal based both on taking up the theme of self-management and the taking into account of the phenomenon of exclusion, up to then neglected by the main unions. They combine the traditional defence of the right of state employees with the defence of the workless, the homeless and illegal immigrants, participating in the creation of charitable organizations and multiplying contacts with those religious and lay people who are taking over from the state in matters of social assistance.

SUD is already an integral part of a combination movement such as the purest democrats of our epoch dream of, champions of “the defence of civil society against the attacks of state power”. But the renovated combination movement is rotten even before flowering: it is born out of the decomposition of the former professional trade unionism, based on the identification of individuals with their type of work, and from the emergence of new reformist associations based on the aim of integrating into the world of work all those who have been excluded, so that they become citizens in their entirety. In spite of the good will of a number of SUD members, this atypical trade unionism, as they like to call it, has nothing revolutionary about it….Faced with the institutionalization of the SUD, some protesters propose to limit the duration of delegates’ participation in the co-management organizations and even to elect and revoke them on the basis of only the decisions taken in general assemblies and strike committees. But no formal procedure has ever impeded the appearance of a hierarchy within the institutions even when the base is regarded as sovereign. As long as individuals express the need to be represented, they are always confronted by the fact that the representation that they have chosen escapes their control. » – from here.

Footnotes

-

« Co-ordination des Groupes Anarchistes » – Coordination of Anarchist Groups, an absurd name for a group that only co-ordinates itself. Such a name implies they claim to represent even those anarchist groups – the vast majority – which do not adhere or belong to it. In an epoch where political representation in the form of parties is increasingly rejected, those few anarchists who have joined this bunch of anarcho-politicians are incapable of absolutely any act without recourse to a discussion of the whole of the local organisation, which means that they have to get together days after such acts would have been relevant. Like political organisations everywhere, they represent opposition in order not to oppose – e.g. on a demo against fascists in Montpellier last year, they waited 2 hours before joining the main point of confrontation, sloganising in unison « They will not pass ! » when the rest of us had already made sure that they wouldn’t pass. What had they been doing for those 2 hours ? – chatting to CGT stewards and members just 200 meters away from the main area of potential confrontation.

-

Attacking people slice by slice, rather than all at once.

-

See : http://www.ugict.cgt.fr/articles/references/decryptage-ordonnances

-

« Ordonnances » can be described, for want of a better word, as « government by decree ». But it’s more complicated than this: Parliament authorizes the government to draft “ordonnances” on a particular issue, but not in general, which, in order to become laws, must be adopted by Parliament. And then, the Senate, then the State Council – the “guardians of the Constitution” can refuse this or that order. This has already happened, including on the issue of the labor code! In fact, the Macron government negotiated with the trade unions beforehand, which the Constitution did not oblige him to do. Generally speaking, the description of the”ordonnances” is presented in a deliberately over-simplified manner to present the trade unions as being the main victims, in order to hide the aspects that benefit them and which they have collaborated in. For example, this Guardian article over-simplifies the situation, presenting him as simply by-passing parliament and repressing parliamentary debate: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/sep/22/macron-takes-page-from-trump-change-france-labour-laws

-

Re. the CGT and World War I, it’s a complex issue. The more radical anarchists had lost influence in it, and tensions before 1914 were between reformists or socialist-insurrectionnists (e.g. Gustave Hervé, who from 1912 onwards became an out and out chauvinist.). Lots of rank and file syndicalists put their trust in the ability of Jaurés (leader of the Socialist Party until killed in summer 1914) to have agreements with the German social-democrats in order to avoid the war. There was a lot of confusion when he was assassinated, and probably lots of people were more or less convinced by the State’s propaganda, which had been powerful for several years (the most intense episodes of class struggle had been in the first decade…by 1904 some regions had already become quite pacified…propaganda falls on and nurtures fertile mud – pacification…class peace as preparation for capitalist war). See this in French : https://dissidences.hypotheses.org/5405

-

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Albert_Thomas_(minister) – « In October 1914, the Government gave him the task of organising factories with a view to the intensive production of munitions. In May 1915, he was appointed Under-Secretary of State for Artillery and Munitions, becoming Minister of Munitions the following year. Thomas first became a member of the cabinet on 12 December 1915 when he was made the Sub-Minister of Artillery and Munitions under the Minister of War. Due in large part to the need for more shells for the widely used “Soixante-Quinze” cannon, he was promoted again on 12 Dec 1916 to become Minister of Armaments. »

-

This, along with their secret accounting, allowed the EDF section of the CGT this century to have built, amongst other humble privileges, 2 luxury hotels in Morocco – supposedly to house delegations of union reps to that country.

-

See, for example, « Enragés and Situationists in the Occupations Movement » : – in particular Chapter 9 – “The State Reestablished” – and «Obsolete Communism: The Left-Wing Alternative» by the Cohn-Bendit brothers, in particular pp147 – 195, both of which deal mainly with the manipulations of the CGT.

-

For example, in ‘45 a factory in Limoges, which produced quality porcelain for the rich, was occupied and production took a self-management form ; the workers changed the production line to produce low-priced china for the poor. The CP was part of the government, and the CGT suppressed it.

- Paris: banks splattered with eggs, ATMs smashed, a CCTV camera also…Niort: Socialist Party HQ tagged, cop car tyres punctured, cop cars tagged…Rouen: Socialist Party HQ tagged…Lyon: 1000 continue demo past official route and try to break through police barrage; a few missiles thrown; lots of tear gas (video)…Nantes: five 14-16-year-olds nicked during demo, as cops fire tear gas and missiles are thrown at them…Valenciennes : 2,000 people protest in industrial town, clashes with cops, a worker hit by a flashball…Bordeaux: University vandalized during occupation …Loire: man deliberately drives car into police station entrance

11. In Paris on this day, the « Services d’Ordre » – demo stewards – of the CGT brutally attacked and hospitalised a woman and some of her friends who’d dared respond verbally to their crude sexist taunts. See this translation : https://libcom.org/news/attack-feminists-during-march-paris-18092017

Thanks to P. & A. for help in writing this

Leave a Reply