an eyewitness account of the Sebokeng Rebellion of 1984

by

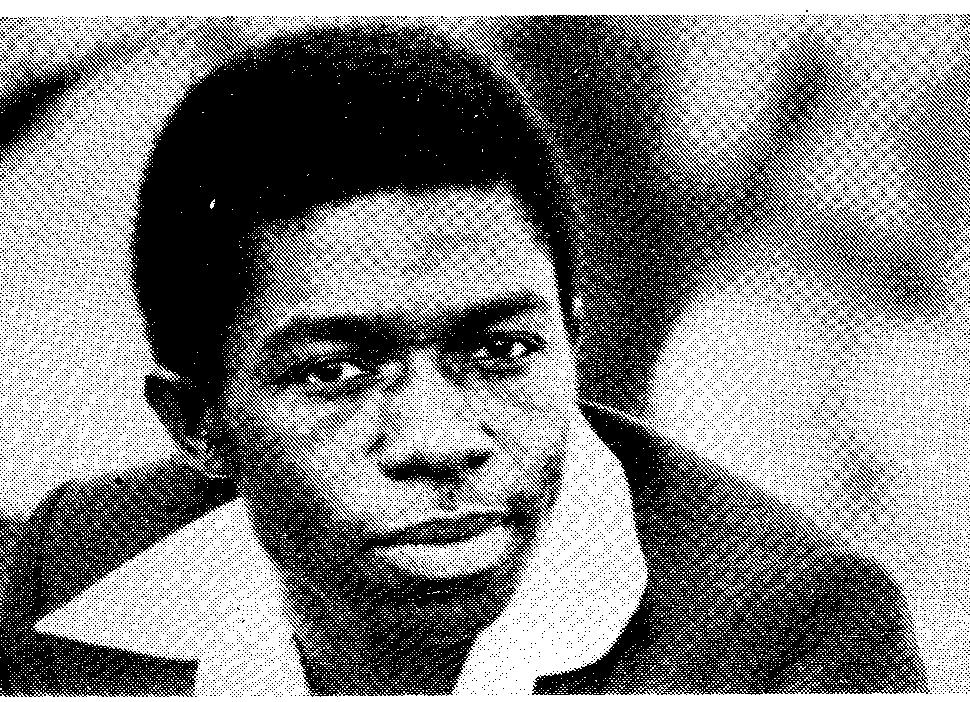

Johannes Rantete

Johannes Rantete was the 20-year-old unemployed son of a factory worker, matriculated, wishing to go on to university but lacking the funds to do so. When Sebokeng, like Sharpeville, Evaton, Katlehong, Soweto and other Vaal Triangle townships, blew up in early September 1984, Rantete got on his bicycle and collected material for an eye-witness account of the uprising. This account, published as The Third Day of September now appears here for the first time on the internet.

Rantete’s first manuscript was completed — together with a set of colour photographs — by 14 September, 1984. It was edited by both Rantete and the publisher over the following month, and the final version published on 14th October; distribution began immediately, particularly in Sebokeng itself. But distribution was hampered by intense police activity, following ‘Operation Palmiet’ on 23rd October when 7,000 police and soldiers carried out a house-to-house search in Sebokeng, and forced all residents to pass through police checkpoints. In mid-November the publisher (Ravan Press) received reports that copies of Rantete’s book had been confiscated by the police, who held them until they had checked with the Publications Directorate as to whether the book was banned. On 23rd November Johannes Rantete was detained under Section 29 of the Internal Security Act, 1982. Security police then visited Ravan Press and demanded the photographs which Rantete had delivered with the MS, and which were the basis of the black-and-white line drawings which illustrated the book, though these are not included here. But, because of their documentary interest, the photos had meanwhile been posted to another Ravan Press author, working on an illustrated history of South Africa since 1976. They apparently never arrived. In a telephone conversation with Ravan Press, Captain Kruger of the Security Police stated that until the photos were recovered the interrogation of Rantete could not begin. Ravan Press, having managed to obtain a photostat set of the photographs, then collaborated with the apartheid police by issuing them to the police. One can well imagine the use to which they put them. Rantete was released on 14th December: he had been held in isolation and questioned, but not otherwise ill-treated. Meanwhile on 7th December The Third Day of September was banned. Ravan Press appealed against this ban and on 3rd January 1985 the appeal was successful. Distribution of the book resumed. It went well in the city bookshops because of media attention. But distribution continued to be difficult in Sebokeng itself: the police had succeeded in intimidating both distributors and readership.

Despite being full of naive, and some obviously ideological, reflections (e.g. belief in “good leaders” elected by the people, belief in God, appeals to Africa etc.) the text is very interesting because it shows how far the South African revolution went. A young black guy I know in South Africa spoke to someone who was involved in the movement in the 1980s and he told him that probably about 20,000 young blacks in each city and town recognised that they had no future and went about furiously attacking the misery of their imposed conditions. In the film Amandala! an older black guy spoke of “our youth driving the country into the sea”, bemoaning that their attitude was purely negative. Unfortunately the forces of positivism (eg Mandela and the ANC) won out against this healthy negativity, to produce the arguably worse conditions prevailing in South Africa today. It’s a pity that those who were involved in this amazing movement – today’s older generation – have little to say to the younger generation facing an even more intractable form of capitalism (neoliberal whilst officially multi-racial) about the strengths and weaknesses of the struggles of the past that could help towards elucidating the contradictions of today’s movements.

Anyway – here’s the text, which if nothing else, shows how far the revolution went and shows how far it has retreated since.

The Third Day Of September

Rising Rents – the True Source of the Turbulence

Can it be denied that the riots of Sebokeng were part and parcel of the fight for liberty by black South Africans? Although the motive was to strike against the rising rents, the course taken by the rebellion was so horrible that even the police could not withstand it. This I say because there was no roof of the business buildings that remained tall after the strikes except the well-planned Mphatlalatsane hall, Perm building and various churches.

In Zone 11 all the shops were burnt down. The rent office, the bottlestore and the beerhall were burnt . Three houses were burnt. One councillor was killed. Several cars were burnt, including a brand-new Honda Ballade. The petrol station and the soft-drink cash-and-carry wholesale were also attacked. The roadhouse café was broken into and goods were taken away. Tarred and untarred roads in the zone were blocked with stones, boxes and anything else that was easy to carry. The Post Office was attacked and burned, not surprisingly.

All the shops in Zone 12 were burnt down, too . The rent office, the bottlestore, the beerhall, a doctor’s surgery and the house of a councillor were destroyed by fire. The tarred roads in this zone were blocked with stones and pelted with bottles and burning objects to hamper the passing of cars – especially police vehicles.

Zone 13, where there are more shops, was the first to come under attack. Not a single shop carried its original shape. Everything was in ashes. Here again the rent office was attacked, but the library and two clinics were spared. A house near the shopping centre was burnt. Roads used by buses were pelted with stones and broken bottles.

Zone 14 is the undisputed CBD of Sebokeng. It carries public buildings and other large buildings which are not found in other zones . There is the well-known Mphatlalatsane hall, the Perm building, Texido Supermarket, the banks and building societies (Standard, Barclays, Volkskas, United, Allied) and the long frontage of the P & A Dryclearners building. Fire raged through all these buildings. All the shops – a ‘Hire a TV’ shop, a Kentucky, a beerhall, a bottlestore – were burnt.

By the second day of the strikes the shops in Zone 7 wre still retaining their good shapes, but the rent office along the tarred road and a petrol station had been burnt down.

Zone 3 also suffered the strikes. A bakery, shops, a beerhall, the rent office and a bottlestore were burnt.

The third of September has become a historic day. It saw the fulfilment of the forewarned strikes . It saw the destruction of shops and many other things, including the lives of various people and community leaders. As an author who involved himself in the strikes to view all the horrific events of such a rebellion, I would like to bring an important point to the notice of the public and those of us who dream of being leaders.

Paul has said that not all of us should be leaders, as leaders are more punished than anybody else. So, referring that to our situation, no man should just agree to be a leader if he has no true qualities of leadership, and no one should feel easy on the throne he has been nominated to occupy, if he has not been freely elected by the public. This I say because, if you keep on ruling defiant hearts, the time they revolt against you not one piece of your belongings together with your life will remain yours. If people are dissatisfied with you, it is better for you to resign before the terrible dark clouds overwhelm you in your wilderness; if you defy their needs, then you ask for a brutal retribution. This I say to the remaining councillors: that they should never regard their own opinions as more weighty than those of the people they rule; and that the well-being of the community should not be ignored, or the response will be more horrible than the conflagration that destoyed Sodom and Gomorrah.

They must learn that leaders are like children. They do what the community wants. They are called leaders because of the communities which they lead. They need not think for the whole commnity, or approve their dreams without consulting the community. They are held in high esteem because of the porr people beneath their footsoles. So, they must beware: if they provoke the people beneath their feet they will fall painfully to the thorn-infested ground.

Yes, we all know that things go up all the time, but the way the Leko council increasing the rents by R5,95 was simply a request for vilence. The most blamed must be the one who first came up with that idea. That person should expect as much mercy as was shown to anyone or anything attacked during the strikes.

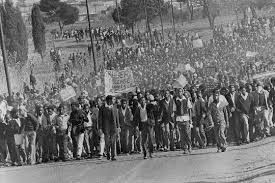

The strikes spread as far as Sharpeville, Boipatong, Evaton and Residencia. All these towns fall under the same council of Lekoa. The strength of the unity among the people to carry out their plans would have won black South Africans something in the early stages of Black Consciousness. The strikes really proved to me that unity is alive and strong among the blacks, but the thing that keeps it invisible is the lack of strong nationalism. What is most fatal to black unity is the numerous parties formed, that often lead to hatred and mistrust.

The strikes took four day and afterwards 31 people were dead. More than 50 were injured and about 8 policemen, while 37 were arrested. The police used teargas and rubber bullets tyo disperse the rioting crowds. Many people were injured and some killed, and the count of police victims will probably never be know, because of news clampdowns.

Some of the victims of the strikes can be identified . The Zone 11 councillor, Mr. James Mofokeng, was killed after shooting two youths, and on his corpse read the placard , “Away with rentals! Asinnamali!”. Ntombi Majola (12) was killed. Nomthanazo Mphutheni was hurt. Evaton’s deputy mayor Mr. ‘Dutch’ Diphoko died in the Sebokeng hospital on Tuesday. Evaton’s mayor, Mr Sam Rabotapi, had to remain homeless after his house was burnt down. His gown was worn by an elderly woman who danced down the streets and called herself the first mayor . On Monday the Sharpeville councillor, Mr. Sam Dlamini, was killed by an angry mob. The boy Wisey Mnisi of Zone 12 was gunned to death. The boy Stevenson Motsamai (13) of Modishi Primary School went missing after the riots.

I Was in the Midst Of All the Horrors

Some weeks before the ‘Bloody Monday’ of 3 September approached, protests against the rent increase of R5,95 took place at various places in the Vaal Triangle. Churches and organisations warned the council time and again, but their words fell on deaf ears. The warning was even published in newspapers that the councillors should resign as they were never elected by the people. The call for their resignation was a clear rejection of the government’s new system of implementing the black town councils which the people didn’t ask for.

Days went by and nothing was said by the council in connection with the rents. During the last few days of August, residents in the Vaal Triangle were informed that on Monday, the third day of September, no one should go to work as it would be the day of protest against the rent hikes. Early on the morning of Friday 31 August pamphlets were distributed by the town council warning residents that if they didn’t go to work on Monday they would lose their jobs and lose their houses, and in turn the future of their children would be doomed. Those pamphlets didn’t have any influence on people. Saturday and Sunday came and passed. Then came the greatest day in the history of Sebokeng, the day of protest, the day of deaths, the day of arrests and the day of teargas and smoke. This day is historically named ‘Bloody Monday’.

As a resident of Sebokeng I was also concerned by the events that were to take place, but was hindered by my parents to remain within the yard. In all my born days I had never found myself amidst a striking crowd, and thus the hindrance laid on me by my parents was as painful as the heart of a divorced man. I multiplied two by two to get an easy outlet from the yard. Thus, by doing so, I secured my curiosity which is the first thing a newsman should have.

I rolled down the street to the Zone 12 stores together with two friends whom I shall call Siphiwe and Xolile. None of the shops was open and people could be seen standing in groups here and there. The main topic was the rent hikes that had hit the whole of the Vaal. We turned back and joined a tarred street which We followed as far as the second bus stop. While walking, I could really feel that something was wrong with ~he atmosphere, and assured myself that something sad was going to eventuate. When we arrived at the bus stop, no vehicle could be seen or heard. When I looked down the road I found that it was blocked with stones. Then we met certain guys. whom Siphiwe knows.

Those guys seemed to be members of a certain organisation which I can’t tell at the moment. They told us that they had stopped all the VTC (Vaal Triangle Corporation) buses, and that people who boarded had been klapped and chased away. Buses were not damaged but kindly told to withdraw from service. From the bus stop we bent down towards the Roman Catholic church near the Sebokeng post office. There was a group of people standing near the post office, all of them staring up in the Vereeniging direction.

I ran to see what might be happening up there in the highway. My eyes sighted a huge crowd along the highway, and another crowd in the highway. When the crowd in the highway approached I realised that it was a white man driving a new blue car escorted by four men, while those others who swarmed around were calling out that the car must be stoned. Truly, it had already been stoned, and its windows were broken, all except the front one. After the white man passed, many people ran down the road to Zone 13’s shopping centre. We used the other street to join the crowd behind a church building.

While we stood there, the police vehicles arrived. Three of them passed down the highway and the last truck turned down to Zone 13 where a number of people had run. This police truck was carrying black police. We followed down the road. The police truck went to stop next to a bottlestore near the shops. A huge crowd approached the truck from the nearby surrounding houses to which they had fled when the convoy passed. I remained hidden behind the fence and watched an interesting drama I would hardly forget in my lifetime.

As the crowd approached, the police jumped out holding some glass-like plastics which they used as shields against the stone- throwing mobs. The police could not withsland such stone-throwing, and the trucks drove off. Some police, seeing that the truck was going, ran for their lives and two of the plastic shields were thrown away. The mob lifted the shields aloft and began to sing. Meanwhile, some people entered the bottlestore and ran out with beers. Others, seeing the beers, crowded into the bottlestore and crates of beers were taken away. The moment the people crowded the open space, two police vehicles arrived and teargas was fired.

Because it was my first time, I didn’t know what teargas was or how it worked. When others ran and hid behind the houses I remained at the gate. A white cop fired a rubber bullet which fell some distance away from me. You know, curiosity sometimes leads to some simple traps. I went and picked up that piece of black rubber and smelt it. I really can’t tell what happened when I threw the rubber away. I became dizzy and lost my strength, and then some pains struck at my eyes. I ran to the water tap and cleansed my eyes with a handkerchief. By doing so I weakened the strength of the teargas. Because I didn’t know, I thought the piece of rubber I had picked up was the cause of my dizziness. This was false, as I later learnt that teargas had been fired across the street and spread on the wind towards where I was standing.

After some three minutes the people returned to the streets again, most of them now having handkerchiefs in their hands. Still the police vans drove up and down, and teargas was fired here and there. The people then adopted a system of pouring water on every pellet of teargas fired. This system became the shield of they strikers, and the police could do nothing fürtber. They drove off to the other zones, thus giving the people in this zone a chance to run towards the shop buildings.

The strength of the riots really took root in Zone 13, as it was the first of the zones to puff out horrible smoke. The crowd gutted the shop of the councilor on the corner of the lower building. They looted the goods. At first the goods taken were thrown and scattered all over. No one was allowed to take them home. But soon the views of the people differed. They looted the goods and took them to their houses. At last the shop was burnt. I kept staring at the scene. I was totally surprised by the fearlessness of the people who set the shop ablaze. Later all the shops were attacked and goods were looted. No police van returned until all the shops had been burnt down.

After setting all the shops alight they sang ‘Ezone 14 siyaya’, meaning that they were going to Zone 14 next, where the mayor’s shops were. The slogans that ruled the Bloody Monday were ‘Amandla! Ngowethu!’ and ‘Asinamali!’ Power is ours. We have no money.

From Zone 13 we returned to our home zone which is Zone 12. When we arrived all the shops had been burnt. Here they included a Save More store, two drycleaning shops, a restaurant, two butcheries, a fish and chips shop and another three shops. From there I checked other buildings. To my surprise a beerhall, a bottlestore and the administration board office had also been burnt. Really, things were bad. At that moment a police truck arrived and people were dispersed. Teargas was fired and entered into a nearby house by the roof. It was filled with smoke for about five minutes. The truck left and people swarmed into the shops again. Later, a group of about five guys rolled out a big safe from the Save More store. The police van returned with the owner of the store. They picked up the safe and made off. The people then began to disperse.

At about five o’clock I went to Zone 11 alone. The strikes here had not been as strong as in the other zones. Only one councillor’s shop and the administration board office were burnt. Some metres away from the shops, a councillor’s house was burnt and a car stood completely burnt with its roof on the ground. This was the zone where it was rumoured that a douncillor was burnt alive. Other cars were also burnt, including a brand-new Honda Ballade. From there I walked until I reached a garage along the highway. Nothing had been done to those buildings, including some shops there.

At last I arrived in Zone 14. Some of the shops had been burnt, but not all. The P & A drycleaning building was burnt to ashes. It was in the evening, and the strength of the riots had reached its peak. People ran down to the Texido Supermarket of the mayor, Mr E Mahlatsi. Goods were looted until it became dark. Then the banks and building societies, including Standard, Barclays, United, Allied and Volkskas were all stoned and set alight by an angry mob. The surgery in the Perm building was slightly burnt. The Eldorado cinema was stoned and half burnt. Some few guys who remained attacked Mphatlalatsane hail and broke the windows.

Meanwhile strikës were also on in nearby Evaton, in Zone 7, and in other townships. By the time Bloody Monday was over more than twenty people had died and many more were injured.

On Tuesday 4 September the strikes continued. Helicopters droned overhead early in the morning and people crowded the streets again. The thing that made the strikes continue was the presenée of the helicopters, dropping teargas here and there. This annoyed the people and brought them into the streets again. On this day all the shops in Zone 11 suffered the destruction by fire. In Zone 7 a supermarket in the upper region was burnt. Freddy’s soft-drink cash-and-carry wholesale was broken into and cool drinks were looted. Empty crates were used to block the streets and no car was allowed to pass. Police in fighting trucks watched without any reaction. Teargas was not used as it had been the day before. By five in the afternoon, a dark column of smoke could be seen over Zone 14. Because I knew things gonna be bad at that side, I took my bicycle which was decorated with Rasta colours and made my way to Zone 14. When I arrived I found it was a Kentucky building which was burning. People gathered around in big numbers. I passed that place and rode towards Mphatlalatsane hall. People were still looting goods from the supermarket. This shows that it was really ‘too much big’. Some people used the windows to enter the storerooms. I saw that two cars in the neighbourhood were burnt.

Before I forget I would like to inform you that the strikes also erupted in the Sebokeng’s men’s hostels. It was still the middle of the same day when I took my bicycle and hurried to the hostels. What drew me to the spot was the smoke I saw in the distance. When I arrived a lounge had been burnt, and all the shops, the administration board office, and the Masoheng post office which stbod alone some metres away from the hostels. The police vans and fighting trucks were camped near one of the already-burnt shops. Nearby, a dark smoke like that puffed by a steam locomotive filled a room in one of the hostels. One man managed to extinguish the fire while others watched unconcerned.

On Wednesday 5 September it was quiet early in the morning, but when two helicopters arrived, commotion started and havoc reshaped. When the helicopters disappeared it was quiet for the whole day. 13y midday, Siphiwe (a student at Mqaka senior secondary school) and I took a survey of Evaton and Zone 7. We first went to Congo Stores which are some distance from our location. The shops were all closed. Then we walked round the depot of the VTC buses to Evaton. To our surprise no bus could be seen in the camp. Then we understood that the buses had been taken to the Vereeniging depot- in fear of the people. Even the PUTCO depot in the neighbourhood was empty. We walked through the lower part of Evaton called Small Farm. There we saw that the shop building of the Indians had been burnt to ashes. On our way we saw several cars burnt out. Some shops had not been touched but a beerhall was burnt. We saw other Indian shops which had been gutted. The roads were blocked with stones and other materials.

We then entered Zone 7. Here the atmosphere told us that the strikes had not been so serious. We walked for a long distance without seeing any damage. I was really worried by that. It seemed as if, while other zones were protesting, this one had been holding parties and other things. The people here seemed to be cowards. Only some children could be seen in the streets, while their mothers and fathers seemed to have locked themselves in their yards. It was only near the shopping centre that there was any sign of violence, but still at a low profile. The shops and other things had not been burnt as in other zones, but only the administration board office and a petrol station.

Does it mean that they wanted to secure their tomorrow’s needs by leaving out the shops? Were the rent hikes not a burden on~their necks too? Are they laughing at the other zones who burnt everything? If they were vexed by the rent hikes they should have done the same as everyone else that Bloody Monday.

Brothers, if the time to fight has come, we ought to fight. There is no need to watch how the other partner is fighting. I don’t support the destruction of shops and offices, as they play a role in my daily existence, but if everything is to be destroyed, then let us destroy and not exempt even a single thing. Let us not lose God’s support by doing injustice; that is, doing harm to some and securing others, whereas they are all on the same elevation of guiltiness. Let us not be like King Saul, who infringed by securing King Hagat whereas ordained to exterminate everything by God.

We are Africans and brothers in love, and ought to share the pains of bitterness and the fruits of joy.

From Zone 7 we returned to our home zone. At three o’clock I took my bicycle and rode to Zone 14. I looked everywhere, but the strikes were dead. I went back. When I crossed the highway I noticed police vans and cars around Freddy’s soft-drink cash-and-carry wholesale. At a distance there stood a scattered crowd. The roadhouse in the neighbourhood had been broken into and its goods looted. The petrol station was half burnt and bottles from the wholesale were scattered all over. This day did not suffer such riots as the two previous days.

The following days were the days of hunger. People have nowhere to get food. They have to travel long distances to the outskirts to seek food and other commodities. Some people even cut pieces of meat from a living cow which escaped. It ran about without some parts. People used the trains to go and buy in Vereeniging,

On Thursday the Vaal buses were released but did not enter the townships. They used the outskirt roads. On Friday they were brought back to their usual service. On Thursday a mass meeting was I~eld between the residents and the director of housing for the Orange Vaal Development Board, Mr P Louw. The discussions concerned the rent hikes. People demanded that the rents be lowered by at least R5 a month. In Sharpeville they demanded a ceiling of R30 per month. Mr P Louw could not decide the matter there and then. He thus postponed the meeting as he will first meet the Orange Vaal Administration Board.

How Did the Eye of the Government View the Riots?

The Minister of Law and Order, Mr Louis Le Grange, visited all the townships torn by the riots in the Vaal. He was accompanied by other cabinet ministers like Mr FW De Klerk (Minister of Internal Affairs), General Magnus Malan (Minister of Defence) and Dr Gerrit Vii joen (Minister of Education and Training). Mr Le Grange denied that it was the proposed rent increase that had led to the violence which swept through the Vaal Triangle. He blamed certain forces and organisations for the riots, but he didn’t mention which were responsible. It is a simple fact of life that the demands and grievances of the black majority are never met by the government. It really was the rent hikes that led to the unrest. People showed their deepest concern by rioting, but the Minister of Law and Order dismissed that motive, being unable to feel how rent increases affect the people.

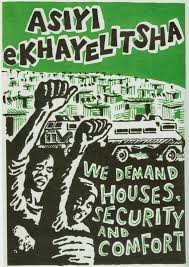

It seems as if the Minister’s denial of the cause of the strikes is a plan not to meet the demands of the people concerned. The increase in rents would have driven many families away from their houses. Black families are really experiencing some hardships. Things are becoming worse and worse for them. The GST has been increased. The majority are being paid less. Many people are being retrenehed from their work, thus increasing already high unemployment. To worsen the matter, the Lekoa Town Council decided to increase the rents by R5,95 which is really too much for this community. The normal rent paid, excluding water and electricity, is already R39,30.

In Sharpeville a delegation of residents led by Rev Ben Photolo demanded the following from the Lekoa Town Council:

* All rents to be decreased to R30 a month;

*The release of all the people detained or arrested during the unrest;

*All members of the Town Council to resign.

A Sharpeville rector of the St Cyprian’s Anglican church, Rev Tebogo Moselane, is the figure who has been blamed for the erup tion of strikes across the whole of the Vaal Triangle. He was blamed for giving the anti-rent organisations his church in which to hold their services. Rev Moselane reappeared from his hiding place after allegations that he had been detained. He is a thorn in the flesh of the authorities and remains fearless of any mishaps that may confront him. He really is a good leader.

The statement released by the Lekoa mayor, Mr Mahlatsi, that they have been forced to increase rents because the council has paid R1,9 million from the accumulated funds to subsidise rents, is understandable, but the council failed to look carefully enough at the misfortune this would bring to the communities. Councillors are wealthy and do not pay rents, thus they ignore the fact that the hikes will do more harm to the families of the poor people.

The mayor showed us how brave he is by going on to say that he is popular with the people, and that he will make personal contact with the residents so ‘that he can restore peace and stability. Something amazing,, in view of this, is why he left his home and sought refuge outside the township he governs. How could people burn his home if he was really popular and significant to them? Why didn’t he make a personal appearance to the people when the strikes were at their height?

I am too much afraid for his life if he does what he said he will do during the press conference. He remains vehemently behind the rent increase without considering the brutality done to some of his colleagues. He announced that he was waiting for the increases to be gazetted before he introduces them. This shocking announcement was seen written in big block letters on the front page of the City Press of Sunday 9 September. It vexed the people so much that most of them demanded the killing of the mayor.

Really, the mayor’s life is in danger. Although he survived the horrible riots, the mayor must be always vigilant. He must know that he has planted an everlasting hatred that will continue to create a barrier between the residents and himself.

The Riots Continue as the Lekoa Council Fails to Respond

The Lekoü council remained totally calm in the face of many demands from the residents of the townships the council is supposed to represent. The mayor – continued to emphasise that the rent hikes would be implemented, although this would only happen in 1985. This response remained negative as far as the residents were concerned. What the residents wanted was a cut in the rents.

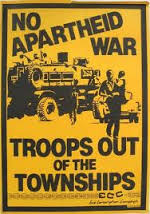

These contrasting views led to the continuation of the strikes. The ensuing strikes were not as strong as those of the third day of September. People now had nothing to damage to show their defiance. But still the police and the army remained behind their heels with teargas and guns. The presence of the police in the townships often brought the strikes to the boiling point. Wherever they appeared with their vehicles people began to gather and riots followed. If the police had not made continual appearances in the townships and if they had stopped ~patrolling with their helicopters, there would have been no such warm riots as the Vaal area experienced.

People held meetings in churches but after their functions the ~police opened up with teargas to disperse them. During the funeral of the victims of the riots the police arrested about 600 mourners whom they accused of attending a banned funeral day, although there had been no specific warning. The court actions added more anxiety to the wounded hearts of the residents.

At last the anger of the people reached the VTC and PUTCO buses. Buses were attacked and windows broken. The youths swarmed aboard the buses and drivers were forced to drive them where they wished. Any motorist passing on the road had to raise his hand to show his support for what they called ‘black power’. He who failed to do so had the windows of his car broken.

When the schools reopened on 26 September no student in the Vaal area was seen in the school yards, nor seen wearing a school uniform. What was the cause of their staying away, whereas the strikes were sim mering down? It remained hard for me to understand until the following day when I made an enquiry of some of the students. The answer from one of them had this ring to it: ‘It will be too difficult for us to go to school when some of our mates are languishing in jail for unspecified infringements.’

This response revealed the strong national solidarity that exists among our students. My own nerves went tough as I learnt again that blacks have something to boast of. I felt confident that if the treasure (nationalism) of the blacks is well secured, then no hail nor storm will uproot it from its basic core of indefinite depth.

As the days went by, students marched to police headquarters to seek for an answer on the rent hikes and request that their friends be released. Unfortunately their request was not met, and thus the schools remained empty throughout the following days. The boycotting of the schools must be ascribed to the council for its failure to respond to the students and its delay in coming to an agreement with the residents. The weakness of the council was that it failed to notice that the strength of the riots lay in the hands of the students.

While the council remained in a quandary, everything in the townships remained in gloom. Students didn’t attend schools, food and other necessities were found with difficulty, buses no longer entered the townships but used main roads only, criminals got their chance to kill people, and illegal trading sprang up everywhere. Residents could get no peace as some mobs threatened their lives. In addition the security police hunted people involved in the strikes from their dwellings. It was rumoured that the people arrested were to be released on bail of R200 each. This sum, peopie said, was to cover the whole amount which the residents had refused to pay in September, though the money colleçted couldn’t cover all the damage done.

When we take a political view of the course of the riots that swept through so many black towns, we must conclude that blacks showed that they rejected the inauguration of black town councils. They didn’t ask for the system and didn’t vote for the people who partook in the elections, but still the government went on to implement the system. The councillors thus didn’t repre sent the people and only perpetuated the will of the whites. They never cut the rents the way they spelled it during the elections. They went on to take good care of themselves. They soon owned chains of shops and many other things. Everything they did began to provoke the residents and warnings followed that they should resign. They ignored the calls and continued to annoy the people by increasing the rents.

The strikes were really so alarming that the government ought to have intervened. But the government feared to meet the demands of the people. It feared to give the blacks their free reins as that would spell danger for its own position. Instead, the utter ruthlessness of the police became the answer to the crying masses and many people died as a result. The people continued to strike despite the deaths of their fellows and friends.

It was not wise for the police to use guns during the-strikes as the suppression of strikes under duress of arms won’t solve the problem. In reality the government has no choice. It has to continue ignoring blacks while meeting many criticisms from outside and many attacks from within.

I ask if South Africa will survive the irtreasure of the South African government is resistible forces of history. Really, the crumbling. It can’t resist the criticisms and attacks it faces every day. The solving of the problem by meafls of tortoise-paced reforms will give the state a jong headache, The blows from outside get harder.

What l hope for South Africa is that all the races within the country should partake in the systetn of government so that we can look at each other’s imperfections and guide each other in all spheres towards perfection. If we cooperate together on all levels of mutual interest to the fullest possible extent, then I cannot see any obstacle that can thwart us.

Postscript: How the Strikes Claimed the Life of A White Infant

The riots in the Vaal went as far as to claim the life of an innocent baby. For a time the situation in Vaal townships was stable. But at last came an incident that nearly reversed the situation. Zone 7, which I had been watching with a critical eye from the beginning, became the battlefield. It battled to show its bravery, and that led unluckily to the death of an innocent infant.

That sad event came after the funeral of Nicolous Siphiwe Mgundlwa, a standard two pupil at ZithuleleLowerPrimary School. Siphiwe was chopping wood at his home when he was allegedly struck by a rubber bullet on 24 September. He was admitted to the Sebokeng hospital but died the following day. During the preparations for his funeral in Zone 7, an executive member of the VaaI Black Priests Solidarity Group and chairman of the Vaal Civic Association, Rev. Lord Mc- Camel, appealed to the police to stay away from the funeral service. The police didn’t stay away from the township, and new strikes began to take shape.

After the funeral the youth barricaded the roads with stones and pelted passing motorists. On that Friday buses from Vereeniging Civic Centre and elsewhere in the Vaal no longer entered Zone 7. They all turned at Fowler, the last Zone 12 bus stop.

Things were bad again, Mzala! People gathered in threes and fours and what came from their mouths were words of consternation. The road was still swarming with stone-throwing youths when Mrs Kay Gordon of Walkerville drove down that way, without any knowledge of the situation. With her were her eldest son, Jamie, seven years old; Blair, her three-week-old baby; and Mrs Annah Ram areletsi whom she was taking to the Orange Vaal Administration Board. I am sure that Mrs Gordon didn’t know that things in the Vaal were bad again, otherwise she wouldn’t have used that road. The windows of her car were broken and one stone hit the infant, who failed to gasp the air after the fatal blow. Jamie was also hurt.

The background to the deaths of these two children in Zone 7 was the ruthless shooting done by the police. The force used by the police outgrew the anger of the communities, which is really wrong. It seemed as if the cops were permitted to open fire at anybody whom they felt like shooting.

I remember another incident, in which a boy who was about to be delivered back to his home afte7r being arrested in the Evaton cemetery was fatally shot by a policeman. The shooting came after the cop made continual threats to the boy by pointing the barrel of the gun at him. It is naturally painful for us as residents to live at gunpoint. Really, no one can live freely when death threats are -made continually. Such actions of the cops took inhumanity a further step beyond the boundaries.

After businessmen and pressmen had toured the strike-tom areas, the Orange Vaal Administration Board announced some plans of forming a paramilitary police force to deal with any future unrest in the Vaal. The l~oard wanted the police to demonstrate the upperhand of law and order to the residents. If such a system had been introduced earlier it might have driven the situation from worse to worst as I have already indicated; the presence of the police and soldiers in the townships was provocative to the residents, and it would have meant all-out war against the communities. By that plan the Board showed its misunderstanding as far as the riots were concerned. It planned to suppress instead of negotiating with the residents to solve the indaba.

Sebokeng You Are Great

In that unmeted anger you broke out into

Violence to overcome the forces of oppression

Imposed on you by your fellow brothermen.

The wrath you showed was more than

That of a tempted black mamba

When you demolished everything to ashes.

You puffed horrible smoke from all

The corners of your zones

While from your lips came words of condemnatio

You stood for the first time united

By one zeal as if you are

The children of the same mother.

You remained dauntless although the barrels of

The guns pointed at your faces.

You never retreated

When friends beside you

Suffered the fatal shootings;

You showed what really makes a record.

I learnt that no cop can curb

You in your provocation

Nor try to harass you with a gun.

Your anger resembled that of a monster.

You snarled at those who turned down your request

And made some to be known no more.

You made a history that none of your residents will ever forget.

Your reaction so shocked the government

That it could not believe the damages done

Were only a protest against the rent hikes.

Wrath of the mainba, zeal of the united, courage of the history makers —

I bow down to admire your everlasting greatness.

**************************************************************************

You can buy this text, with its not really interesting line drawings, here, at the amazingly cheap price of $31 (for 44 A6 pages,the equivalent of 11 sides of A4).

For more about South Africa on this site, see South Africa: a reader

Hits as of 4th December 2016: 2620

Leave a Reply